Provided by Jenna Yow

Killing Our Gods: Imperial Icon in Silence and That Which Faith Demands

Killing Our Gods is a monthly column from Grace Benfell about Christianity, religion, and role-playing through a queer, Marxist, and lapsed Mormon lens

The iconoclasts destroyed images of God, believing that those images betrayed Them. However, in order for images to threaten God, they must represent something true. In Simulation and Simulacra, postmodern philosopher Baudrillard sees that destruction as a failing effort to hide god’s non-existence. The icon renders God as a physical object, replacing the absent God and thereby showing his falsehood. If God can be so totally replaced, could They have possibly been there to begin with? As Baudrillard puts it, “If they could have believed that these images only obfuscated or masked the Platonic Idea of God, there would have been no reason to destroy them… But their metaphysical despair came from the idea that… These images were in essence not images, such as an original model would have made them, but perfect simulacra, forever radiant with their own fascination.” Basically, if an icon is perfectly representative of God, then there cannot be a God. The icon represents only itself.

What happens when the icon can speak?

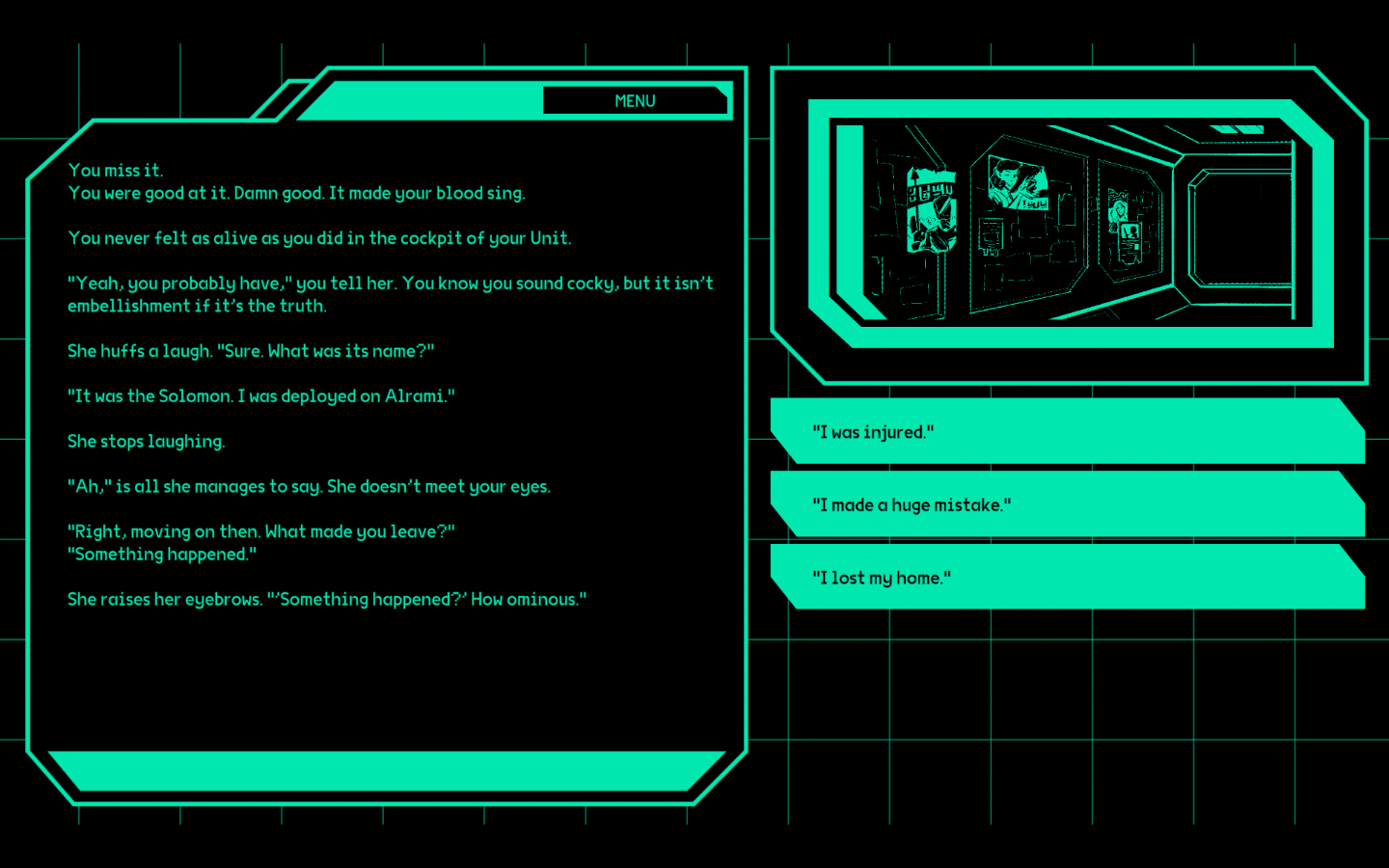

That Which Faith Demands casts the player as a kind of iconoclast, taking apart a mechanized God for a corporation. Gender is left ambiguous. The scant details of their background are chosen in a job interview, after which every player will get the job. The company is desperate for more hands. It does not care whether those are the hands of a factory foreman or a dock worker. The game’s own images are scant and sketchy illustrations; it relies mostly on text for its narrative.

These gods are weapons and icons both, and thereby their material is both expensive and useful. The gods’ bodies are undeniably constructed. They have arms bound in steel, joints hinged together with screws and bolts, glass windows and eyes. They are also something human. They bleed from veins, musculature weaves itself around broken bones.

Yet there is something mythical about them. By falling in patches of blood and oil (what really is the difference, after all?), the player hears the voice of the god’s swiftly dying soul, still present, though its body rots on a battlefield. In the first of potentially multiple conversations, the god rebukes the player, “You are not welcome to my body.”

It’s an appeal to a kind of divine humanity. It is powerful, but also rings hollow. After taking apart the cockpit, you can walk along the God’s spine, finding living quarters. In one part there is a fold up chair and a smutty magazine. This god was always being lived in by creatures that could not claim divinity. What you are doing is not new. This god wielded more power than most of us ever could. Only now, for a moment at least, it is dead… or at least dying. It cannot decide how its body shall be used. Neither can the player character, who has only taken this dangerous, blasphemous job out of necessity.

Similarly, one cannot separate the death or life of a god from the empire it represents. The ongoing war between The Sabiq Empire and The State of Zaira is hazy. However, the invocation of empire itself and the game’s implication that it is sometimes difficult to tell a citizen of one state from another implies the fuzzy, violent borders of colonial conflict. All this affirms an uncomfortable truth: God is not just God. Their message cannot be shared without the weight of empire.

Silence is a movie about that weight. The 2016 film, based on the 1966 novel by Shusaku Endo, follows two Jesuit priests as they enter Japan in the 17th Century. They seek to restore the honor of their teacher Crisóvão, who is rumored to have apostatized, as well as bring their own god-granted authority to the floundering remnants of Christian communities. The ruling samurai of the Tokugawa Shogunate have outlawed Christianity across the island.

The two missionaries, Rodrigeus (played by Andrew Garfield) and Grupe (played by Adam Driver) arrive on the island to celebration. They are quickly taken in by a christian community, relieved to finally have two men of authority among them. They begin to perform communion, to hear confession, to baptize. Soon the activities get the attention of the local authorities. What follows is a slow drip of dread, as Rodrigeus and Grupe, as well as the christians they shepherd, are discovered and the Shogunate goes to extreme lengths to force them into apostasy.

The film’s central concern evolves to be icon. In order for priest and congregation alike to reject their faith, they must step on an icon of the savior or spit on a crucifix. The question then becomes: At what point have we forsaken God? At what point have we denied Them? In the first of several anxious scenes, Rodrigeus and Grupe watch as the authorities gather up prominent members of the town and urge them to step on an icon, to show that they are not Christian. The tests escalate, with town members arrested should they fail to step or spit. Eventually, after Rodrigeus is captured and Grupe killed, the onus falls on the lone priest to forsake his faith. Unless he wishes to watch more good Christians die.

It would be easy for the film to paint the men who put Rodrigeus and the Japanese Christians into this existential bind as villians. Silence deftly resists this, instead making characters like Rodrigeus’ unnamed interpreter and the shogunate official Inoue Masashige into vivid, human figures. The interpreter in particular, played by Tadanobu Asano, at once aches with empathy toward Rodrigeus and is fundamentally dismissive of his plight. He points out that the priests come to Japan with the urge to teach, but not to learn. He speaks fluent Portuguese, but no priest has ever learned Japanese. The empathetic characterization of these figures emphasizes Rodrigeus’ (unwitting) colonial aims. The isolation of Japan was not, as it might seem now after the destructive efforts of Japanese Imperialism, a purely nationalist maneuver. It was instead, at least in part, a protection against the massive forces that would exploit it.

This is Rodrigeus’ naivety. He frequently proclaims that Christianity can exist in harmony with Japan, failing to acknowledge, or even know, that guns lurk behind his cross. The fact that there are no ordained Japanese proves this. Divine authority can only come from Europe. With this light, the montage of priestly graces earlier in the film becomes a horrific testament to Rodrigeus’ ego. It is the height of arrogance to believe that one can truly represent God, can be like him, because of authority granted only by men.

When I first played That Which Faith Demands, I chose to be former clergy. In a sense I was; I had once been a naive missionary. The choice changes little of the proceeding narrative, but gives it an existential weight. The game is coy about what god this is or whether you used to worship it, but it is not hard to extrapolate the discomfort. In the job interview, when my character declared themselves as former clergy, the interviewer asked if they knew what they were doing. They replied that their faith wouldn’t be a problem. This was, of course, a lie, but it was a lie that the game did not judge me, or them, for. The player character in That Which Faith Demands is in a desperate place. Their home was destroyed, and they need money in a plea to return to their family. The narrative voice does not judge them, even if the god they dissect does.

This has a kind of echo in Silence. Finally, Rodrigeus finds his former teacher, who encourages him to apostatize, having fully assimilated into Japanese culture. He also rings aloud the truth of Rodrigeus’ mission, grimly saying that the Japenese-Christian martyrs “did not die for God, but for you.” In a dramatic moment, confronted with the death and torture of more Japanese Christians, Rodregieus acquiesces. Then a miracle happens. The icon speaks aloud to Rodrigeus, telling him that it is okay to step on him and that “Your life is with me now.” It is when Rodrigeus rejects God’s image that he can actually bear Christ’s mission. It is a brilliant overturning of Baudrillard’s former statement, finding God in the absence of both icon and ideal. Believing in grace, in a truly radical, saving grace, means accepting that God saves despite weakness and fragility.

However, That Which Faith Demands does not end with such liberation. It is simply the end of the work day. Tomorrow, the player character and their co-workers will return to dissect another god. When my character honestly accounted their shortcomings to this dying deity, he called them only merciless. For the colonized, for the poor, there is no assimilation into the machine that it is killing them. If there is a redemption, at least without battle, peace, and/or decolonization, it will come with death.

Death, however, can take many forms. After his apostasy, Rodrigeus gains a Japanese name, and helps the Japanese government to identify forbidden objects brought in by dutch traders. However, he continues to believe, still worshiping with his friend and fellow apostate Kichjiro. Rodrigeus lives a kind of Christian life, seperate from all the icons and trappings of Christianity. He is buried and cremated as a Buddhist, but carries a cross til both he and it are rendered to ash. Perhaps that is the lesson. When we let go of a singular, dogmatic god, when we don’t see ourselves as martyrs, but as survivors, when we try our best to live, we can find a god outside of empire.

If you like what we do here at Uppercut, consider supporting us on Patreon. Supporters at the $5+ tiers get access to written content early.

1 thought on “Killing Our Gods: Imperial Icon in Silence and That Which Faith Demands”