Killing Our Gods: The Divine Family of Hades Mimics Earthly Capitalist Structures

Killing Our Gods is a monthly column from Grace Benfell about Christianity, religion, and role-playing through a queer, Marxist, and lapsed Mormon lens.

“It’s in the blood” whispers Orpheus, as Zagreus brings his mother Persephone back to the underground. Back to Hades. Back where she belongs. The whole structure of Hades is a bait-and-switch. Zagreus, son of the god of death, initially wants to escape the underworld, to find his birth mother, Persephone, who until recently he did not know existed. Upon reaching the world above though, Zagreus finds that his body cannot take being on earth for too long. He can live in the world above only for minutes, eventually his blood will call him back to his home. So he escapes again and again to see his mother and convince her to come back. The game is then about reconnecting a family, building a home. However, Hades’ vision of a family is wound up with heteronomative ideas, resulting in a fundamentally regressive construction of divinity and home.

Fitting with its central thematic concerns, Hades has a number of stats and items that persist between runs, and many of them are decorations and upgrades for the House of Hades. Entire runs can be spent on paying for better couches or statues for the living room. There’s also ambrosia, which serves to let you curry affection with the Olympian gods or deepen relationships with folks at home. All of this makes Zageus the center of a great web of connection. He even helps repair the classic romances of antiquity. While playing Hades means dealing destructive violence, progressing in Hades means making or remaking connections with every major character. While the game starts with a compelling central conflict, it turns into a story where resolution is as easy as getting the right item or a particularly good run.

To be fair, Hades gestures at broad conflicts. If, for example, the gods on Olympus found out that Zagreus was not actually escaping. In fact, he could not live with them even if he wanted to. What if Demeter, Persephone’s mother, knew that her daughter can in fact be found, that several of her relatives knew where she had been taken? Hades’s motivation in lying to Zagreus is to prevent a full on war between the gods of the underworld and those above. That threat of devastating conflict serves as a means of setting up stakes. Everytime Zagreus leaves the underworld, he could expose Persephone’s location to Olympus. It must be resolved. Persephone’s return begins the road to healing this hurt.

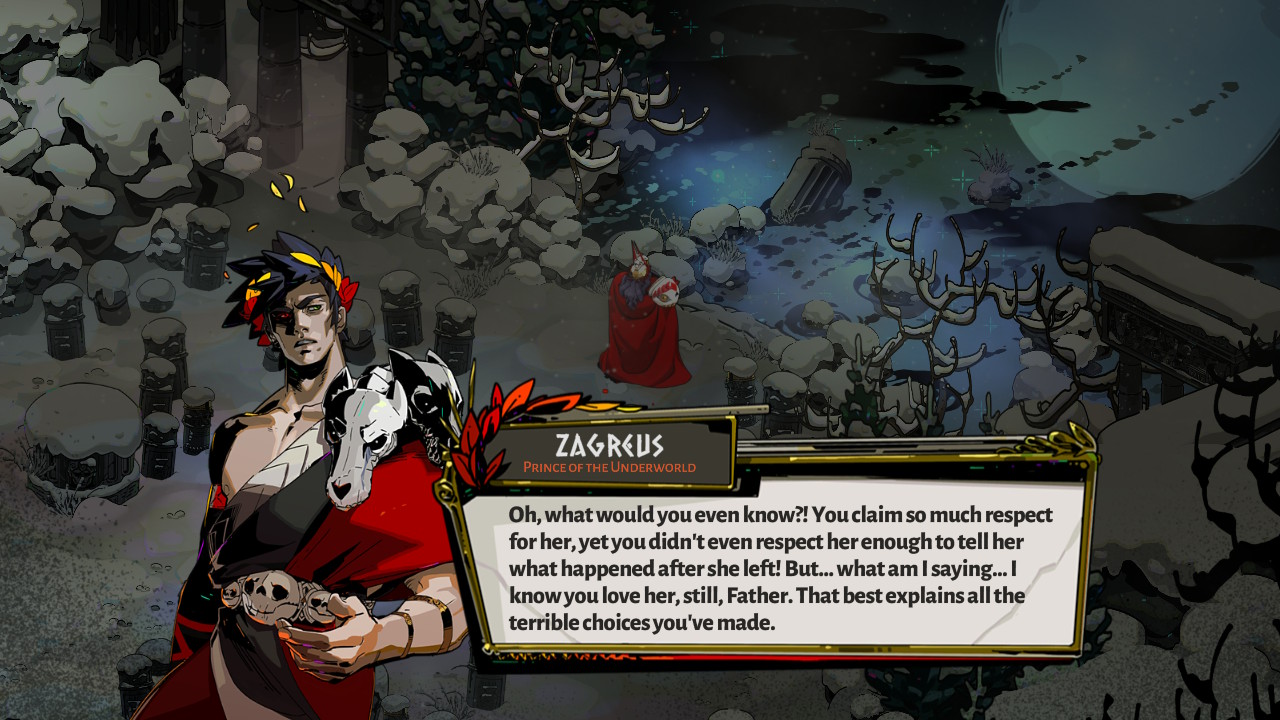

That is exactly the issue. Hades is a game that presumes that such hurt can be easily healed through the right upgrades, a mountain of dead ghosts, and killing your father over and over again. The only vision or idea of restitution is the new construction of the heterosexual family unit. While Hades is gruff, angry, and even abusive with Zagreus, Persephone, the very ideal of a nurturing woman, tempers him and makes up for his innumerable mistakes. While she was gone, Zagreus and Hades were fighting each other over and over again. It was unsustainable. Now, with her, they exist in relative harmony. There is no path for Zagreus or Persephone to live without Hades. You can’t escape the underworld. You can’t escape your family.

Admittedly, it’s difficult for me to think of this outside of that old cornerstone of my mind: Mormon theology. In mormonism, the final saving ordinance is a marriage or a family sealing. This ensures that the family connection will continue into the heavens. There are productive counter threads in theology. The sealing is ultimately of every person back to God, rather than just a family unit to each other. This makes the sealed part of a community of believers, to which they are all equally responsible. In practice, this is not how it works. Single parents, and single people more generally, are shamed for not having the proper configuration of family. In cases of divorce, even when it is because of abuse, sealings are usually not annulled, with a promise that “things will work out in the afterlife.” Queer relationships are completely barred from sealings. What is allowed to be eternal are the things which fit into white supremacist patriarchy. I want to be clear that this is not how all Mormons think. However, these are systemic problems. It is difficult but not impossible to escape them.

Hades clearly pushes against this in some regards. The face of the divine is multifaceted, multiracial, and has multiple genders. Ultimately though, it is a story of reconciliation. It is a story of finding, not choosing, one’s proper place in the universe. Which is ironic given the myths it is drawing from. The items Zagreus uses to kill his father are the same weapons Hades used to kill his. In the Iliad fate crushes the souls of its characters, killing them in ultimately pointless battle. The gods are fickle, resistant to anything that threatens their power. Hades borrows all this, but places it a much friendlier context. The underworld is a fun place to fight things, not a cruel one where the dead are left to rot. The gods are your cool friends, not unknowable beings with their own agendas. The game is afraid of lasting conflict, of real blood. Because of that fear, it falls into a deep well of conservative subtext.

Many of Hades’ problems went under-discussed: its fatphobia, its ableism and its reconstitution of greek myth in both regressive and progressive ways. Its heteronormativity is what lingers for me. Zagreus’ explicit bisexuality, every character’s pretty vanilla hotness, as well as the admittedly lovely subplot between Achilles and Patrocles, distracted everyone from the fact that it is about the reconstitution of a nuclear family unit after trauma and abuse shattered it. We are all living in the shadow of heteronormativity, in the damage of family-led, not community-led, care. I want to imagine a world beyond the trap of families left alone. I want to imagine a world where we can choose who to be with, where birth does not mean everything, and communities uplift and help each other. Zagereus’s very blood prevents him from finding such a world.