Scars of the Risen God: Healing in Pathologic 2

Killing Our Gods is a monthly column from Grace Benfell about Christianity, religion, and role-playing through a queer, Marxist, and lapsed Mormon lens.

Content warning for self-harm, surgery/other medical procedures, and violence.

Spoiler warning for Pathologic 2

1.

To set a bone, you might have to break it again. To heal a heart or a brain, you might have to expose it to the open air. Removing a bullet or shrapnel might require more wounds or leaving the cause of injury within, never to leave until flesh rots off bone. Surgery requires recovery. One must heal from healing.

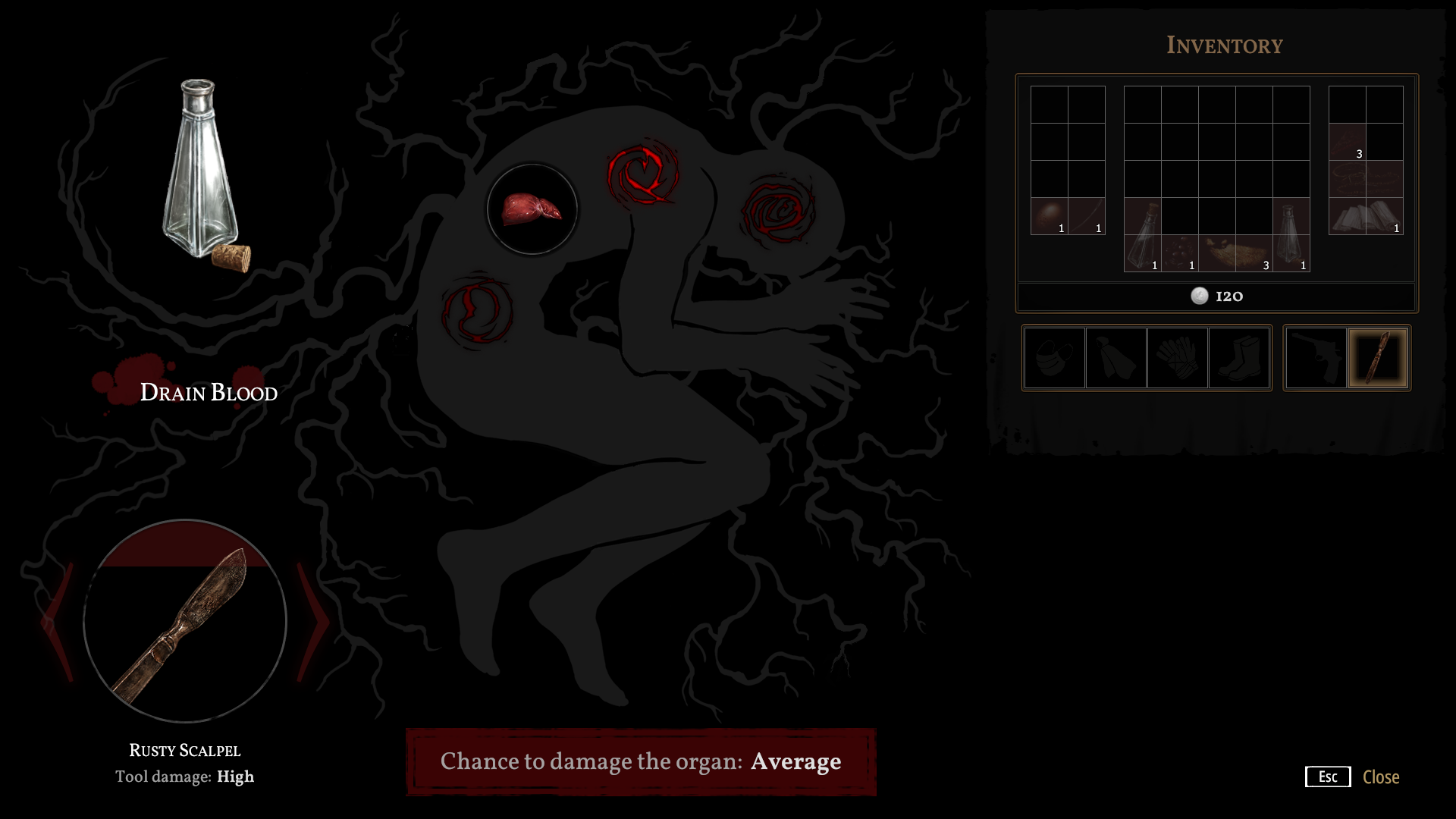

Pathologic 2 cuts this truth down to its most basic elements. Protagonist Artemy is a Mehku, one of the few in the Kin, the game’s fictionalized indigenous steppe culture, allowed to cut bodies open. The game itself describes the role as “those who know the lines of the body. Those who have the right to make cuts. Those who know how to disjoint joints in a way that pleases earth.” As a plague of that same earth ravages his hometown, he remakes the organs of the dead into potions to halt it. Even the town suffers from a variety of wounds. Each district is a body part or an organ, cut up like a bull on a butcher’s table. The roads are lines cut into the earth, giving division to what is really one wholeness.

The town is a body. Artemy is a knife.

A knife is just a tool, it is not good or bad, but it is never an easy thing. To make a potion that saves a child’s life, Artemy must cut a dead man open, boil his plague stricken heart, combine it with herbs taken from the earth, and feed it to a sickly mouth. It is an unpleasant business. Crucially though, Artemy is no mad doctor. These methods work. If the town and/or the earth is one body, this art of healing is the simple act of prioritizing. It is as natural as decomposition, but no less unbearable to look upon.

Thus, at its core, Pathologic 2 is a game about healing and its unpleasantness. But, rather than asking “what kind of healing will I bring about,” it asks “what kind of wound will I inflict?” and “what healing will that wound facilitate?” Through the limitations of time and the body, you cannot save everyone. At the end of every day you will hear of more deaths. More lives you were unable to save. When you take time to heal one person, you lose that time for another. In healing you will wound. There is no other way.

2.

Christianity, generally, is also about healing. The numerous miracles of Jesus Christ, documented in the gospels, are miracles of medicine. Jesus made blind men see, gave the speechless speech, let the paralyzed walk, and cured lepers. What he offered in his teachings was spiritual healing, freedom from the burdens of the physical world. Those who believe will “not perish but may have eternal life” (John 3:16). Christ’s sacrifice in the garden and on the cross was a cure for sin and death, the things that befall every person who has ever lived. In the final days, all things will be made new, restored to a godly glory (Revelation 20:5). The very premise of Christianity, then, is a great healing work.

However, when Christians talk about the resurrection, they often mean a very narrow, normative idea of perfection. As one might imagine from a mythology that shows the removal of disability, heaven is often shown to be a stale, frictionless place. In my Christian tradition, bodies are divine, God himself has one, but the bodies we have right now, are not. The process of the resurrection, then, is one of perfection. The bodily struggles, like broken bones or failed memory, will disappear. We will all be like a thin, white, able-bodied, and masculine God. We will be made anew in the image of the divine as shown in Sunday school manuals. Nonconformity will vanish in God’s cold glory. It is nigh impossible for someone who is a racial minority, queer, disabled, and/or neuro-divergent to imagine themselves in such a heaven. It is cruel to try and make them.

However, the very image of Jesus contradicts these narrow standards. Christ proves his divinity through his wounds. His hands and feet were nailed to the cross. His side was pierced by an empire’s spear. Those wounds remain in his glory. Thomas, the apostle demanding evidence of his teacher’s resurrection, stuck his figures inside Christ’s chest, felt his scar, and knew that he was divine. Mortality defeated, its signs lingered. Few traditional Christians would doubt Christ’s perfection, but his body fights their standards. While time and tradition erase much, his wounds can not be taken away.

The type of healing Christ offers then is not neat and easy, but messy and nonlinear. Christ tells us to pluck out our eyes (Matthew 18:9) to “eat his flesh and drink his blood,” (John 6:53) to make ourselves profane and embodied, to wound ourselves, and him, in healing. This is not to say that one can justify cruelty, but that what looks like a wound from the outside can really be a healing sign. There are wounds that heal. In a broken, often evil, world, that is a simple truth.

3. (spoilers really start here)

At the end, Pathologic 2 offers two kinds of healing and two kinds of wounds.

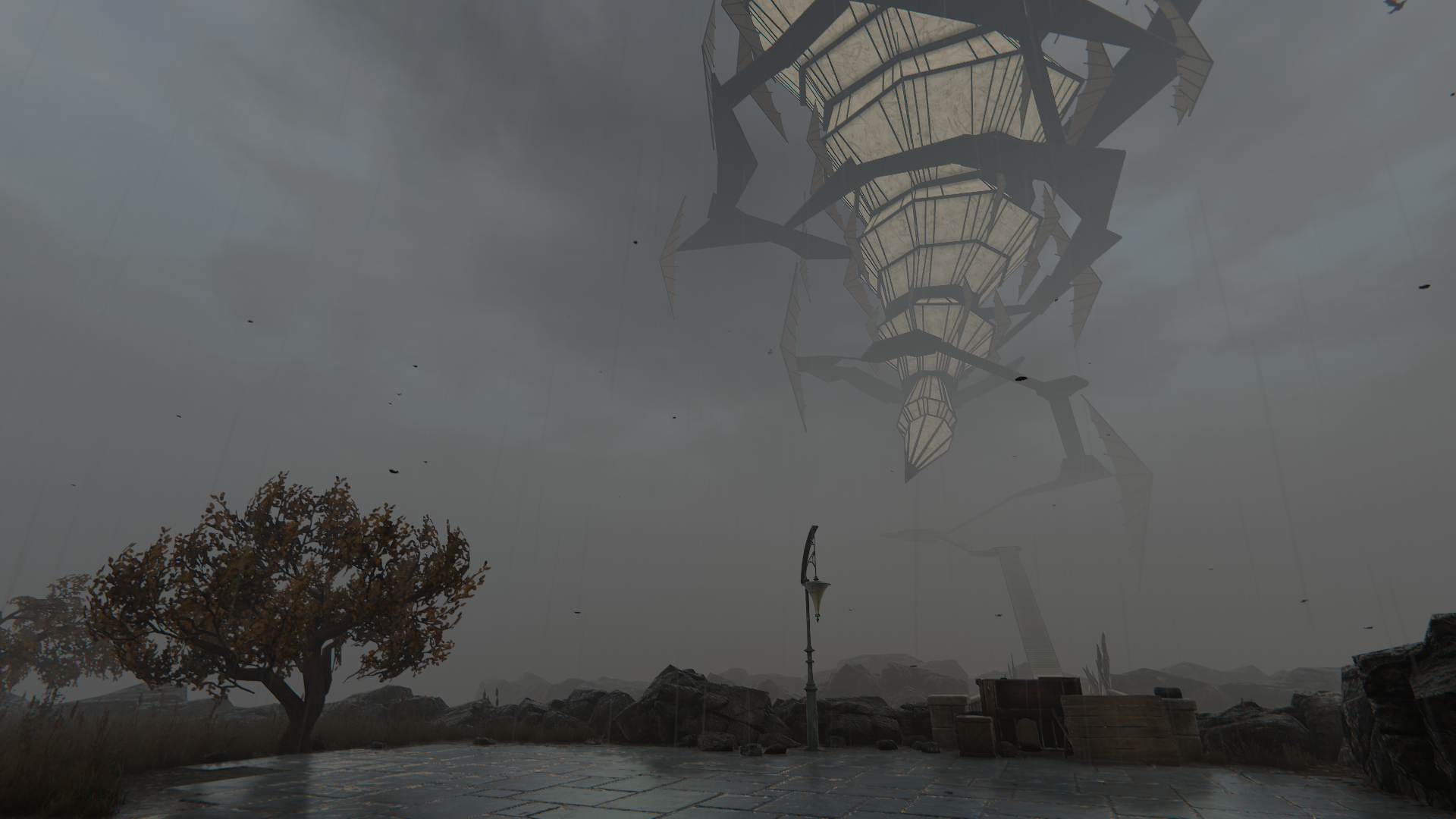

The massive building at one end of the town, the Polyhedron, pierces the literal heart of the earth. The plague is then the screams of that earth, crying for relief. But there is a twist. Destroying the Polyhedron and thus removing the splinter from the earth’s heart would cause the earth itself to bleed and die along with much of the indigenous culture of the steppe. The choice is then: kill the infection, maintain the town, and cure your friends or let the infection remain, the town crumble, and the earth live. Both offer a cure. Both offer a wound.

In their powerful essay, Lotus draws out this choice as an illustration of the difference between liberal and revolutionary politics. The choice is not really between the cure and the earth, but between the maintenance of the cruel system that allowed the plague to thrive and its dissolution into a new world. One where, pointedly, the people of the Steppe get their land back. They write: “Plague was never the true enemy. The crisis is racial capitalism, settler colonialism, the ongoing historical processes that weave the intolerable fabric of everyday reality for Black, indigenous, poor, incarcerated, queer and trans people.” That crisis demands an answer. If we, and the earth, are to survive, it requires a destruction that heals. It requires an attack on the heart of the world. In healing we will wound. There is no other way.

I believe a better world is possible. I also believe the birth of that world will be painful. Birth, and healing, cannot be anything but. However, it will be a glorious pain, a sacred pain. That world will take time. It will take more scars and more work, more pain and more struggle. It will take generations for the trauma of colonialism and capitalism to shake off humankind’s shoulders, but those times will be all the more glorious for it. I take comfort in the fact that the perfected world is not one where all bodies are alike, not one where difference is erased, but one where care is everywhere and we bear the wounds we choose.

In Brooke Larsen’s essay “Scars,” to which this one owes a debt, they describes their vision of a resurrection morning: “I see us with our scars from mortality—marks of our struggles and sorrows—and, like Christ’s, they will not be imperfections but a triumphant symbol of who we are.” Much has changed since they wrote it in 2007, and I first read it in 2017, but these words remain true to me. Like the wounds on Christ’s hands and feet and in his side, like scars and stretch marks, they are imprinted on my heart, written on my skin. Just as I believe that wounds will heal, that what others might call imperfections are just signs of humanity, signs of our defiance, our healing. Despite the terror of the plague, and the town that let it rage, Artemy believes it too. He steps into the roads, knowing that his knife can do good. He opens his flesh to the hostile air, so that he may cut.

This was quite the read. I never really stopped to think how messy the healing Jesus offered was and how it stood in contrast with the cold and “perfect” heaven. A great piece of work.