Thousand Threads: Only Connect

My apartment is two miles from one of the largest cemeteries in Brooklyn. It’s big enough that you can get lost inside, as I did the last time I was there. Travelling from one side to the other, you see a small stream, a brief splash of trees, the occasional monument standing above the shorter, simpler gravestones. It’s almost always crowded with people walking their dogs or having a picnic on one of the grassy hills. Occasionally, though, when it’s too cold to be out or when you’ve walked for long enough, it feels like you’ve been transported somewhere else—away from one kind of crowd and into another, quieter, lonelier one.

There’s a cemetery in Thousand Threads, too. In the game’s desert area, you can find a mountain path and travel up, until the sand starts turning to snow. You can walk across a bridge into a white almost-void, dotted with some trees, passing no one. Eventually, if you keep going, you’ll round a corner and see a cluster of stones jutting up from the white ground. There’s no sign, but it’s obvious what it is. When I found it, I spent minutes just standing there, looking at the rows.

Since its first trailer released in 2016, Thousand Threads has marketed itself as a game world that remembers you. It places you and your tiny rechargeable health bar into an open world that can be navigated as you choose from the start, whether that’s picking flowers, helping out your neighbors, or delivering mail. It’s possible just to wander, as though you were playing a walking sim, but if you’re one for setting goals, you can build a set of tools for foraging, find the collectible artifacts that dot the map and do as many favors for people as you can. As soon as you speak to one of the world’s residents, who are distinguishable from one another by their colorful clothes or streaks of paint on their faces, you enter into a delivery-based mission system, where characters will ask you for items– four mustard yellow mushrooms, or a windbreaker, or a bar of soap– or favors in exchange for money. Completing these favors also grants you kudos with the character you helped, which introduces you to the game’s main conceit: not only can characters take note of what you do, they will make sure everyone else knows about it as well.

Each of the game’s characters is procedurally generated at the start, and comes with unique family connections and rivalries that are invisible at first. Not only do they take note of your decisions and treat you accordingly, they’ll also tell their family and friends about what you’ve done. Break up a fight, and the instigator’s opinion of you will go down; start one, and those you attack will dislike you. And the consequences don’t stop there; the families of the person you attacked, and their friends, and their enemies, will all have heard about what you’ve done, and while some of them might stay out of the drama, others will take it very personally.

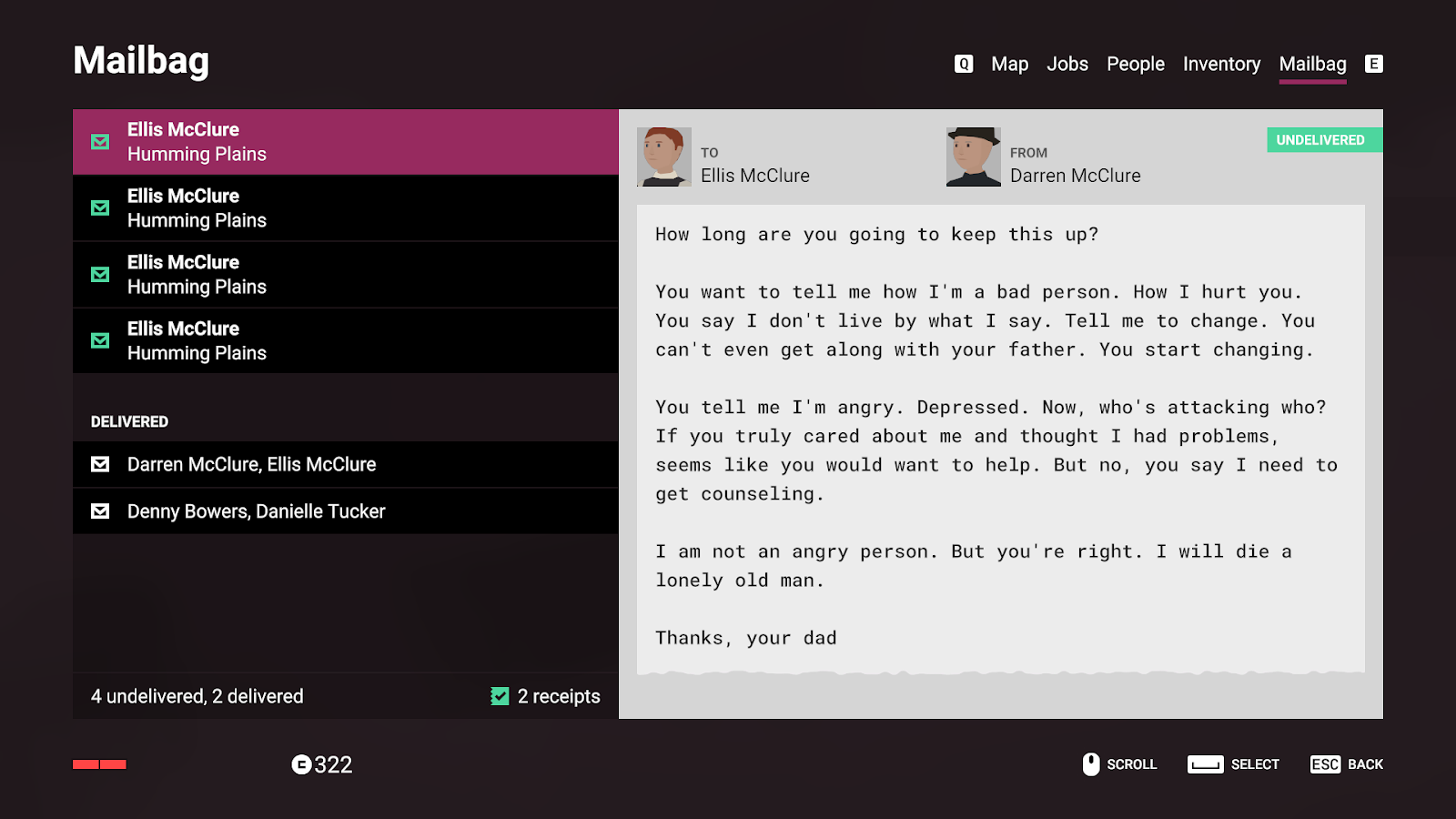

Early on, you find a mailbag and gain the ability to deliver letters to people scattered around the world, as well as read them if you’re nosy. During my five or so hours of play, I only delivered a few—partly because recipients can be hard to find, but mostly because there’s so much else going on. Travelling between this game’s ten or so regions sometimes feels like going to several small towns around the one you live in. Not everyone knows everyone else, but many have heard rumors about each other; others will have parents or children who’ve been the victim of someone you’ve already met. Eula Macneil attacked several people in a town in the foothills, while in the desert her grandfather complains she won’t visit. Two brothers sit by a forest lake, wondering where their sister has gone. In the plains, she’s holding up Gretchen Anderson for a bucket and two necklaces. If you help her, you’ll get one of them.

Since its launch in July, the game has added fast travel and an optional “peace mode”, which gets around the problem of diplomacy. Playing without these, though, turns the game into a much more methodical affair. If you want to get somewhere, you’re going to have to walk. And if someone recognizes you on the way there, you’ll have to deal with the consequences.

Opting out of violence in the original version, as I tried to do at first, means a lot of time spent running from danger. In the first few minutes of wandering around in the woods, I came to a small wooden house, where a man sat outside. He introduced himself as Armand Mercer, and told me there was a villain running around in the woods named Jose Austin, who had stolen his grandmother’s antique clock. He was too old to take revenge; his bones ached. Would I beat up Jose for him?

I refused, then walked away to gather mushrooms. Minutes later, a bear sprinted out from the trees and mauled me. I respawned and walked to the nearest town, where an angry dark-haired woman threw a rock at me and then sprinted away, while the rest of the residents watched me with curiosity. As in real life, even if you refuse to start shit, there will always be someone who has a problem with you. And so, eventually, I abandoned my pacifism and started searching for Jose Austin.

My descent into petty crime brought with it another unexpected difficulty: violence is hard to avoid in this game, but it’s equally hard to commit. The first item you pick up is a stick, which you hit people with by holding the right mouse button and then clicking the left. I played with my laptop’s trackpad (yes, I know) before switching to an ancient Xbox controller, but whatever control scheme you use, swinging your weapon still has a tenuous connection to your intentions. Knocking someone out, as you’re asked to do on numerous occasions by the people you meet, often devolves into running back and forth and barely missing them with your stick, while eyewitnesses look on and occasionally decide to join you.

When you’re not beating people up, if you wander around, you can have dozens of conversations with folks just sitting on their doorsteps, who, unprovoked, will start telling you about someone they know. One resents being asked to participate in a homemade gift exchange. Another will wax poetic about friendship, revealing that recently they were feeling blue, until a friend came over and spent an hour listening to them. Although the texture of their lives is limited by their repetitive dialogue, there’s a real sense that these people know each other, and that you’re simply listening in to the results of a system that’s been generating drama and heartbreak for a long time before you arrived.

Really, this is a game about memory. It delivers on the promise that people will remember what you did or said—if not the exact words or actions, then the feeling. Reading peoples’ messages to each other and listening to what they’re trying to say involves wading through a mix of disarming directness and refusal to say what they really mean. And the procedurally generated nature of characters and their respective locations means making your own landmarks as you wander around, and slotting people into them— for me, Edna Webster lives by the giant rock in the plains, while her father lives far to the south, next to a cluster of purple trees and a neighbor who hates his guts. People and places are marked by and mark each other, while your map only shows you colored squares and the occasional house or mailbox—it’s up to you to fill in the gaps.

If violence creates connection—and it remains the easiest way to connect in a game like this one, even as rife as it is with deliveries, trades, and favors— it also creates memory. But while it might bill itself on the strength of the interpersonal encounters you have, this is a game that’s often very lonely—after all, you’re looking in at a community that you’re only a part of via networks of exchanging fists, letters, or money, not preexisting friendship. The awkwardness and strain of violence, the exertion it takes to commit, reflects this better than its absence ever could. All violence in Thousand Threads, while it has immediate effects, is ultimately interchangeable. A set of people with one last name will hate you for beating up their cousin; another set with another name will love you for it. If you kill someone in this game, most other people fail to notice; even their family will stop hunting for you, given enough time. Do it again, and the results will be identical. In fact, Steam reviews from players who’ve killed every NPC reflect a similar game world to the one that already exists: beautiful scenery, haunting mail messages, but no one to interrupt it.

In using violence to prove its connections work, Thousand Threads undermines them. By centering so much of its action around reactions to you, it creates interpersonal relationships that can be moving but more often come across as shallow, repetitive, or transactional. The vast majority of the memorable moments in this game, and moments of connection with its world, come when you’re alone. After spending so much time by myself this year, I expected what would grab me in this game would be its promise of building networks of relationships, but what actually remained meaningful to me in the time I spent with it was its scenery, and the ways the world interacted with itself while I watched it unfold. Stumbling across an unattended fire in the middle of a featureless desert, or finding a secret lakeside cabin ringed by hills of yellow grass, or reading a goodbye note that I was never meant to see, gave me more satisfaction than any mission I completed or letter I delivered. It’s these monuments, devoid of life, disconnected from time, that hint more than anything at the possibility of interiority– that beyond their shared dialogue and generated grudges, these people can live, love, and die, and leave some evidence of it behind.

Some of the gravestones in that cemetery in Brooklyn are hundreds of years old; the names on them have been washed away, or they had no names to begin with. Others have a few letters, covered by moss, legible but unreadable. Given enough time, maybe they too will disappear.

1 thought on “Thousand Threads: Only Connect”