Why Video Games Need More “Very Special Episodes”

Television in the 80s and 90s used to have these relevant-for-the-time episodes that most viewers now know as the “Very Special Episode.” It was an episode of a sitcom or family drama with a mostly white cast, where they would challenge some aspect of society that we thought of as wrong. Sometimes it was why teenagers shouldn’t smoke or have sex before marriage. And sometimes it was racism. We would get an episode about a character using a slur and learning the hardships of being black or brown. The character apologizes, life moves on, the audience claps. Or something along those lines.

With video games, we cannot quite get the “very special episode.” When we do, they may be subtle. We may miss the moments where the developers were telling us “this is bad,” ike, in Final Fantasy X with Wakka’s racist beliefs against the Al Bhed. However, It is rarer still, when the developer goes a step further. When the developer tries to challenge racism and perhaps to an even greater degree, show anti-racist support by giving the player that experience on a tarnished platter.

Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas, the first game of the series where the protagonist is Black, throws a handful of themes at players from the start. Police brutality and corruption, classism, drug addiction and gang violence, to name a few.

It certainly makes sense to show these issues through the lens of Carl Johnson, but did we necessarily need the scene where Officer Pulaski points a gun at CJ’s head while he digs a grave for himself and Officer Jimmy Hernandez?

The examples are sometimes subtle, and if you blink, you’ll miss it.

Examples like these also try to hide the racism, by including a character of color–or in this case two. In the “High Noon” mission, where Pulaski pulls the gun on CJ, it is actually Officer Tenpenny–a black officer–who orders CJ to dig and for Pulaski to keep watch. There’s that classism again. However, to ignore that the act is still racist, despite Tenpenny giving the order, is an example of how showing this in a video game does little to have the player question what they’re seeing. Similarly, it does not quite drive a point home. It is just racism for the sake of showing racism.

You can assume Rockstar Games did not add the scene to be racist. But, let’s continue just a little further.

Later in the game we are treated to the cast of characters watching the trial of Officer Tenpenny. Again, a black officer. All charges against him are dropped, and later the city begins to riot., upset with the outcome. CJ and his brother, Sweet, go back and forth about how the hood is being destroyed.

“They just tearing up their own neighborhood. Nothing good is gonna come of this,” Sweet says to CJ.

In one way, Rockstar seems to acknowledge that people would be angry about the outcome of corrupt officers not receiving justice. But the narrative leaps to rioting, likely only to mimic the riots of Rodney King in 1992. This also feels as though the game looks to escape some kind of responsibility, by making all the characters involved, Black. As if to say “it can’t be racist if they’re all Black.”

Perhaps it is easy to be more introspective 20 years after the events of Rodney King with similar police brutality and inequality issues still on the horizon.

Still, is there more to these scenes, and others like it, than to just to show life in 1992 pseudo-Los Angeles? What is the message? Is there a true message?

Despite the fumbling of some of these scenes, one thing does ring true. Racism, and the continued marginalization of communities of color, have the power to cause intense unrest in our society.

Racism, and even classism, can be hard to properly show in more interactive media. Unlike television, with video games, it is not about just showing racism, but even going so far as to make the player feel the racism. Experience it without experiencing. Literally taking a walk in another’s shoes. Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas does not quite deliver us our very special episode.

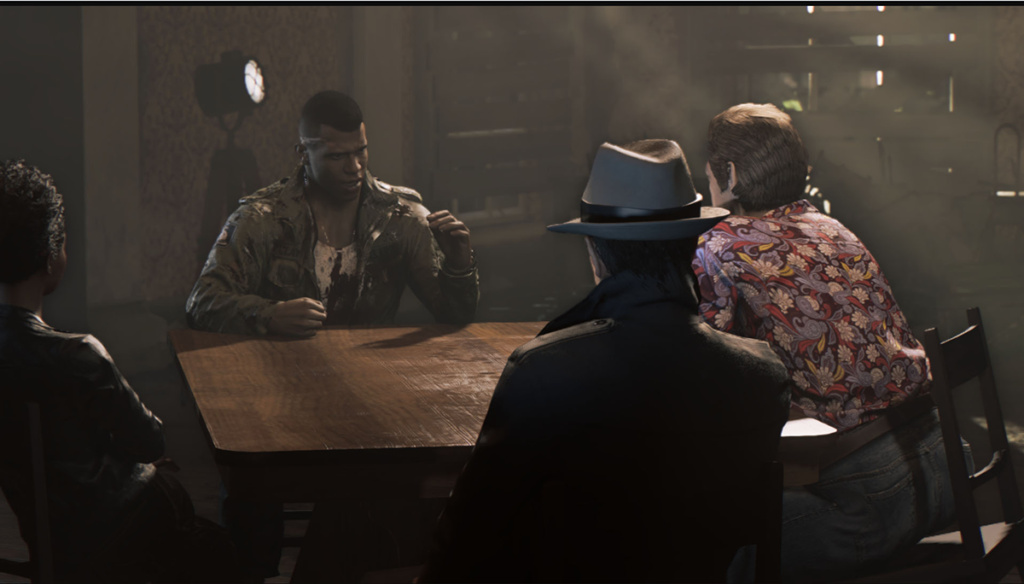

Let’s talk about the Mafia series. In particular, Mafia III.

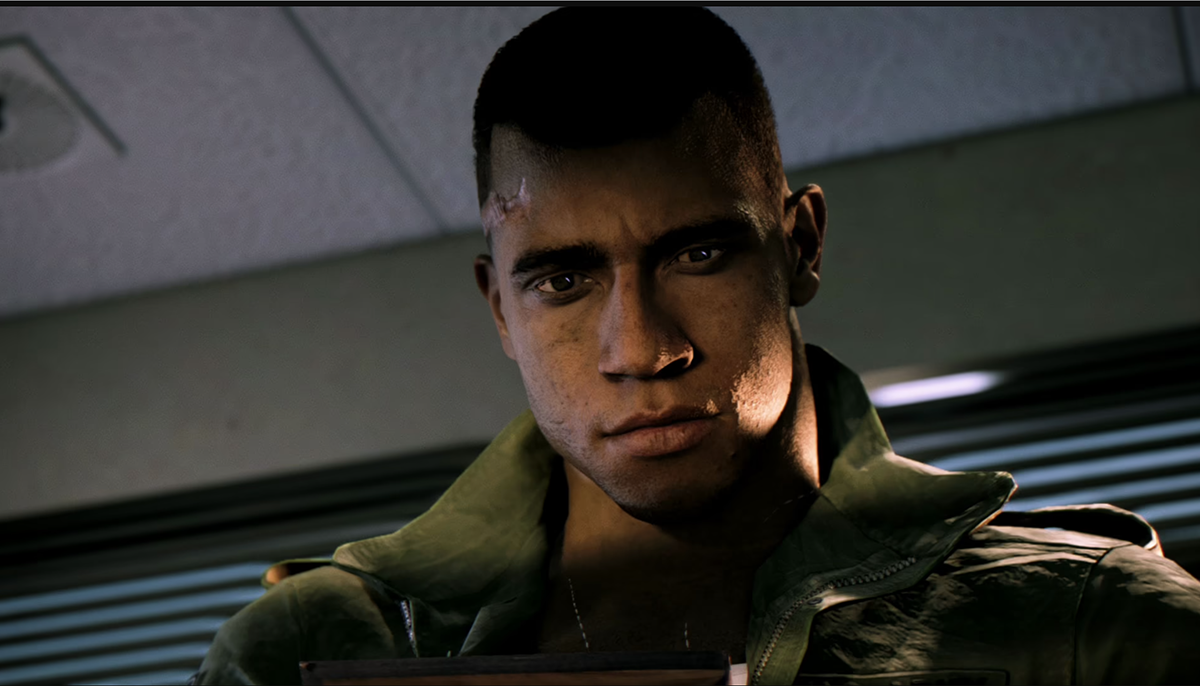

Mafia III deals almost entirely with race, in such a way that the player may have never experienced before. Players take the role of Lincoln Clay, an assumed-Black character. Assumed, because the game states that we do not actually know his heritage or where his parents come from, and believe he may even have a white parent. But, because he looks Black, he is Black.

Clay is ex-military, living in pseudo-Louisiana during the 1960s, still within the Jim Crow era. His family is involved in the Mafia and for a time work with the Italian mafia in the area, until things go South. Pun intended. Clay goes on a revenge-style rampage through the city, taking back territories and controlling much of the city known as New Bordeaux.

Clay faces more overt forms of racism than CJ might face 30 years later in the 90s: Clutched pearls and stares from residents, police harassment, and even segregation. He also faces KKK members, who have infiltrated every form of government in the city, the Mafia itself–of course–and even have a show on the radio.

Again, why do we get such an intimate, up-close look at racism? Why was it important to the developers to include the fact that if a player walks into a gas station where a sign is displayed that says “Whites Only,” the game treats you as if you are trespassing on enemy ground? Why must we face KKK members and save Haitian immigrants from being auctioned off at a slave trade?

This is the gamer’s version of “a very special episode.” It is not enough to interact with a video game that says “racism is bad.” It is not enough to show the (usually white) character have a come-to-Jesus moment, and realize that they are racist and it is wrong and have the audience clap.

Instead, the game shows the actual horrors of racism. The terrifying consequences of the KKK, and of accidentally walking into a store for Whites Only. The reactions and behaviors of citizens who are scared of you, not for the actions you’ve committed, but simply for the way you look. And the consequences of what happens to a city and a society ravaged by racist laws and behaviors.

Both Grand Theft Auto and Mafia III seem to use gang violence as their vehicle for telling these stories, which again, in itself could be considered a form of racism. But with Mafia III it seems just a little bit more intentional.

As the white Mafia crime family looks to get out of crime, open up a casino, and eventually “go straight”, the Black mobs and Haitian Mobs and even the Irish mobs, struggle underfoot, despite being in the exact same position as the Italians. This works as an example on how “white criminals” are able to rise through the ranks, and eventually to the top.

Unlike Grand Theft Auto where you probably have to Google the racism that you might be seeing, Mafia III forces you to look at exactly what is happening. No guessing, no ambiguity. It forces you to think about what you’re seeing, and attempt to reconcile your feelings about it as whatever race you may identify as.

Ultimately, perhaps that is the point of showing either blatant or otherwise subtle forms of racism in video games. It is the very special episode, forcing you to reexamine your ideals and beliefs, and perhaps even consider not just being “not racist”, but to be anti-racist.

We are more diverse than we ever have been in the past with regard to our media. Our video games still need some work, but the progress being made in gaming to show Black and brown representation is great. But there is still progress to be made. Games, unlike most other media, have the power to tell incredible stories and give the player the experience of roleplaying as someone else. It is in that power, that we can have players to try to understand what it is like to walk in another’s shoes.

When the narrative fits, developers should strive to show these examples in games more often, especially in AAA games made by larger studios. And gamers should confront and reconcile their own beliefs every now and then. It happens in all forms of media. It seems like an antithesis to seek more depictions of racist themes in video games where race could be a factor, but, when approached in a manner similar to Mafia III, it could be a powerful tool in advocating for anti-racism and racial equity.

1 thought on “Why Video Games Need More “Very Special Episodes””