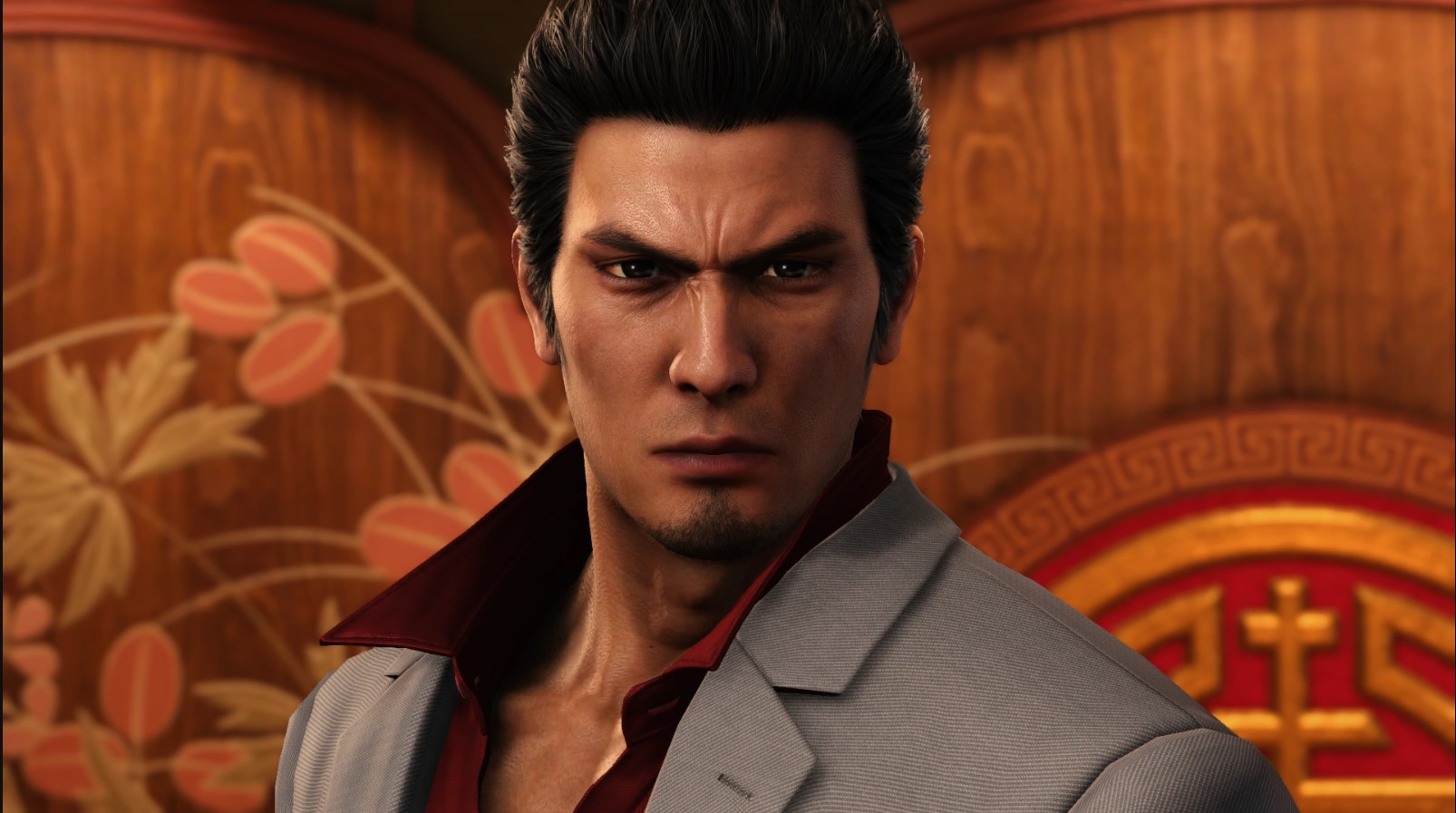

Provided by Sega

Yakuza and The Politics of Crime

There is no merciful light in the gutter ennobling the wretched. No mystical rope will descend to pull them up. For the government of strongmen who promise to clean the streets will sooner deputize the crooks rather than safeguard the meek. The crooks have something the strongmen prize: the will to take. This is the underlying message of Yakuza, a series of such melodramatic hijinks and intense sincerity that it veers into comedy. Comedy it certainly is, in the classical sense, but with an eye toward the permanence of injustice. So there is no move toward a resolution without its sacrifices, just as there is no due law without the dead it should have protected.

As legendary ex-yakuza Kazuma Kiryu, we navigate the treacherous internal politics of the Tojo Clan, a 20,000 man organization of families large and small. They make Tokyo their home and answer to the Chairman, a godfather figure who guarantees the smooth running of operations. But catastrophes abound — billions go missing, rival gangs invade, the government prosecutes — and each time it falls to the exiled, but fiercely remembered Kiryu to punch his way to the truth.

This chain of crises brings up a contradiction, however. The chairman of the Tojo Clan rules from the top of a pyramid. Petty hustlers and high level players both ensure its security. How can we explain this criminal army’s need for a single man? We can’t, that is, until we see the carefully hidden connection: that an inverted pyramid stands above the criminal one, its tip making invisible contact. Each layer of the upper, stronger pyramid rises more consolidated and legitimate as we reach the peak. But the peak of what? Why, of the government, of course.

The dramas and perils we experience as Kazuma Kiryu are the pretext we need to expose that connection.

It is Yakuza 6, the final entry in the series’ first cycle, that provides our table of contents. A small town in Hiroshima Prefecture hosts both a global shipbuilding company and a strangely indepedendant crime family. We fight our way through criminal conspiracy and corporate power in search of the fabled secret that connects them. Some dire revelation hangs over not just the game’s locales, but seemingly the government itself. What could it be? We find our answer in the company shipyards: a not quite lost super battleship from WWII. That’s the great and terrible secret our enemies conspire and murder for? The plot ramps up into absurdity, but its connections to history come pointed and painful, and like Kiryu, we must work backwards through time to understand them.

In Japan, a single party has governed almost without interruption since 1955, the Liberal Democratic Party (Jimintō). The ruling party in the Yakuza-verse is the Citizen’s Liberal Party (Minjitō), a riff on the LDP. The LDP is a conservative postwar creation meant to ensure the survival of as much of the old order as possible. They are the party who deny war crimes and oppose same-sex marriage. During the Cold War, the Americans chose them to enforce capitalist values and suppress socialism.

In the Yakuza-verse, we learn that a major figure of the CPL and former hardline militarist ordered the construction of the Yamato II, a replica of the famous battleship Yamato, the costs paid for with embezzled national funds. Yamato is the shared name of an early Japanese state and of the Japanese ethnicity. Imagine the national identity transposed onto a ship, now watch it sink under a hale of American bombs. Japan surrendered.

The history of the occupation contains at least one mistake we can think of as an original sin. At the dawn of the Cold War, US authorities reversed their purges of the militarists because they wanted a right wing bulwark against the ascendant socialist wing. People who benefited from or directed Japanese imperialism got another shot at power. One of these figures was Nobusuke Kichi, suspected class A war criminal, later Prime Minister under the newly born LDP, and maternal grandfather to Shinzo Abe.

When we’re asked to think of a former admiral ordering the construction of a Yamato II, we see at worst the resurrection of the Japanese Empire, and at best the political mission of Japan’s postwar governance. The idea of a military man in power echoes both the military regime that brutalized the Pacific, and America’s patronage of the military clique after the war.

But the Yamato II is doomed to fail. The project is canceled. The corporation illegally building the ship does not dismantle the vessel, but uses it to leverage contracts and favors. A grotesque relationship thus begins, party and business joined at the hip, the security of one, the prosperity of another. And a third actor, a militant arm to physically protect their secret: the yakuza without which the game couldn’t exist.

During the occupation, such gangs controlled the black markets which provided a de facto economy for the impoverished nation. The defrauding in the black market echoed an earlier grand theft. Historian John W. Dower describes in Embracing Defeat how “a great many men of influence spent most of their waking hours looting military storehouses” of the massive war materiel stockpiled for the brutal invasion that would never come. This combination of bureaucrats, capitalists, and ex-military needed a way to sell their goods. The yakuza provided.

The embezzlement of national funds rebuilding Yamato alludes to this original theft in a way that, with the series’ trademark cynicism, makes it impossible to tell whether we’re discussing a fictional event or real history. This is no accident, but a method of storytelling expressed along different axes.

In Yakuza 0’s 80s extravaganza this axis develops through Makoto, a repatriated Japanese orphan who fell prey to the underworld. The issue of repatriation again begins in WWII. Countless Japanese were left at the mercy of vengeful local authorities. Foreign citizens imported as wartime slaves also remained in Japan. Many never returned. Those who did found little in the way of support. Dower estimates that during this time, the ranks of sex workers swelled with “fifty-five thousand to seventy thousand women, many of ‘third country’ origin.” Makoto shares their destiny for a time.

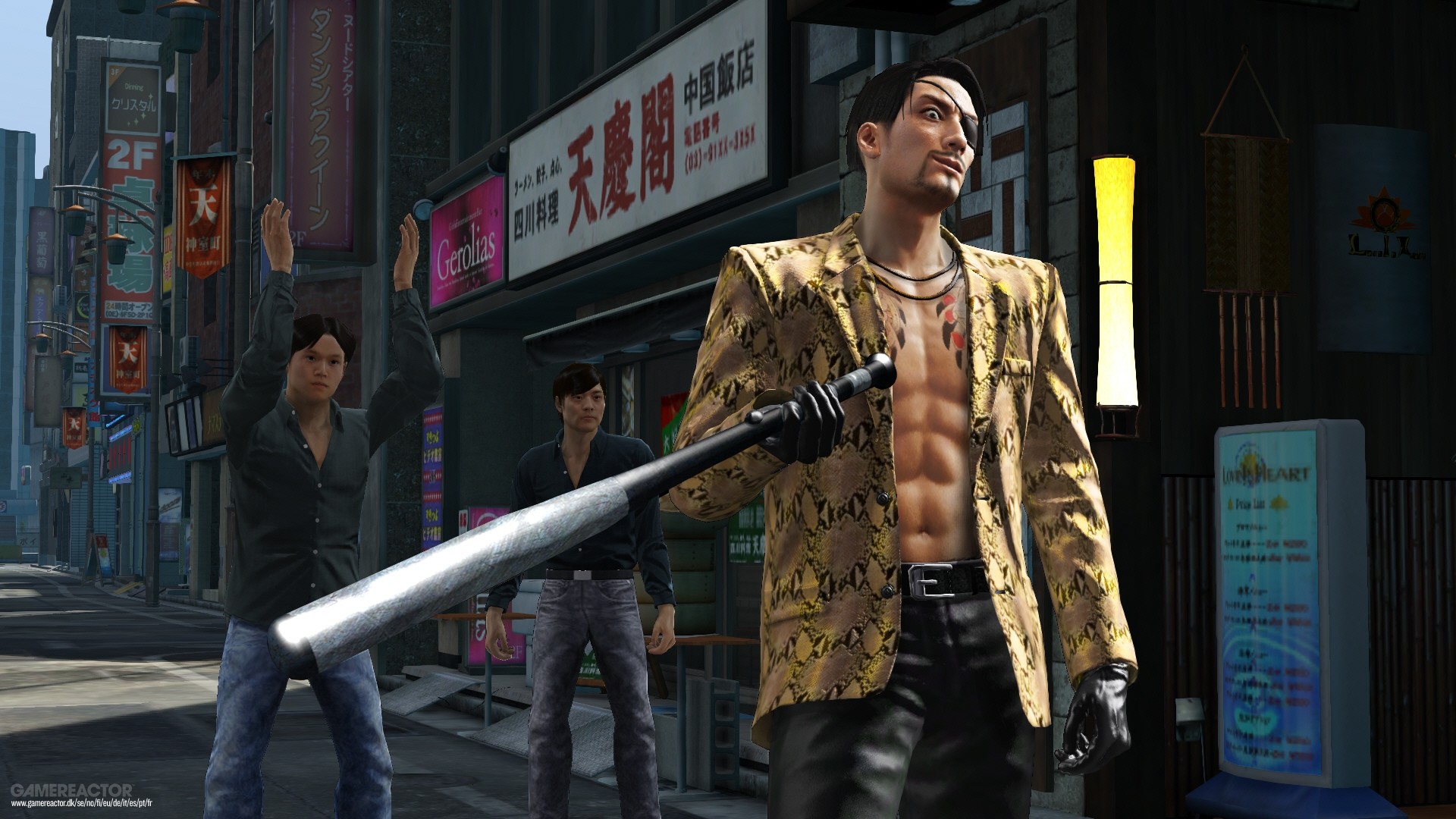

This victimhood forms the backstory to an intrigue that’s nearly as awful. Having escaped human trafficking, Makoto inherits a small plot of land, at last some good fortune. The lot is holding up a billion yen construction project, the series’ landmark Millenium Tower. Commanding the game space, the Millenium Tower is an edifice of capitalism not because of its symbolic size, or even its wealthy occupiers, but because its totally legal construction franchises criminal enterprise into the economy. The Tojo Clan owns all the land save Makoto’s lot, and they waste no time in going to war to obtain it.

The game draws a parallel between the cruelty of the late 1940s and the bubble of the 1980s. The police overlook the silent violence with which the contracts are procured. The Makotos of the world find coercion rather than opportunity in capitalism.

The relationship between patron and sex worker has been predatory as well as clientary, and RGG works very hard to show that the link between different levels of power enjoys a similar relationship. In Yakuza 1, the client head of the Tokyo families amounts to a mere collateral victim of a politician’s power grab. And in Yakuza: Like a Dragon, the politician would have the country bury its sex workers to achieve the same goal.

Like a Dragon describes an under-government for the underworld, with its own checks and balances. It posits that this shadow government looks out for the territory it controls. The unhoused, sex workers, immigrants, the marginalized. The game doesn’t cast the gangsters as charities, or even good people, springing up in defense of others, but rather, as groups formed by the locals in the shadow of the legitimate government’s failure. People who aren’t recognized by the state nonetheless must organize to live. The sex workers of the occupation had their own gangs and turfs, and like them, these newer groups come under attack from a world of respectability.

The 20th century exposed how the brilliantly smiling family of authoritarian propaganda is undone by the real image of wholesomeness: the woman in the birthing bed, the man in the killing field. But the picture did not fade away. In Like a Dragon, the name of the movement is also its slogan: Bleach Japan. Its battleground: electoral politics.

Hate against the unseemly brings an age old rhetorical bludgeon for amoral political climbers, stoking the impotent rage of the poor and assuaging the fantasies of the privileged. We’ll make the world conform, begins the dog-whistled promise, to the trim little garden of our prejudice. In a terrifying bit of insight, this prejudice stems equally from self-hate. The antagonist starts life as a gangster’s son and refashions himself in the image of a model citizen, a politician who will clean the streets.

For this reason, the idea of wholesome and clean comes off as sinister to those who suspect how the streets are cleaned. When local councils pour concrete spikes in the alcoves where homeless people sleep, they are cleaning the streets. When police put black and brown people against the wall, at last they are cleaning the streets. When sex workers are coralled in jail pens, the streets are, for the moment, clean. But only if you think that sex work, blackness, and poverty are dirty.

The police provide a tool to that end. In Yakuza 2, the cops preside over a massacre of immigrants. They don’t get their hands dirty, but the thugs who work with their tacit approval do. As wherever there are people there too is crime, it follows that any human migration implies a criminal migration. In such times pundits will offer local criminals as a possible counterweight against unpoliced abuses by immigrants. Absurd, stupid, and evil, this xenophobic argument lies at the core of the game’s plot, but unspoken, perhaps because the race anxiety is already at work. Japan is one of the most refugee averse countries. But let it be understood: it’s not against migrant workers, but against their naturalization, an attitude that ironically calls on all foreigners to repatriate.

Politics is the process by which we decide how state power will be used. Yakuza focuses on bad actors who try to hijack lawful politics and in the process uncovers that the hijack is business as usual. Yakuza 4 dramatizes the issue as a coup organized by the chief of the Tokyo Metropolitan Police against the criminal establishment. The Chief wants more direct control of the underworld. The underworld nobly resists thanks to the efforts of our fictional heroes. Where lies the statement? In the real world, the act of resistance was never possible, desired, or even needed. Friends take care of friends.

1 thought on “Yakuza and The Politics of Crime”