Press X To Die – How Playable Deaths Shatter the Illusion of Choice

Video games, just like any art form, are too vast to put in one box. However, the one thing that makes video games different from any other art form is the illusion of control through the ability to choose. Unlike movies, books, and TV, where the viewer has no direct say in what happens in the plot, players usually have control over the details of the game’s events to some degree.

Even failures are just a manifestation of the player’s actions. In most games, when you fail, you are immediately greeted with a canned death animation, and a Game Over screen telling you how badly you did.

But what if I told you there’s an alternative to the traditional game over? A scenario where the player has objectively, irrevocably, failed, and there is nothing they can do about it.

And yet the game continues.

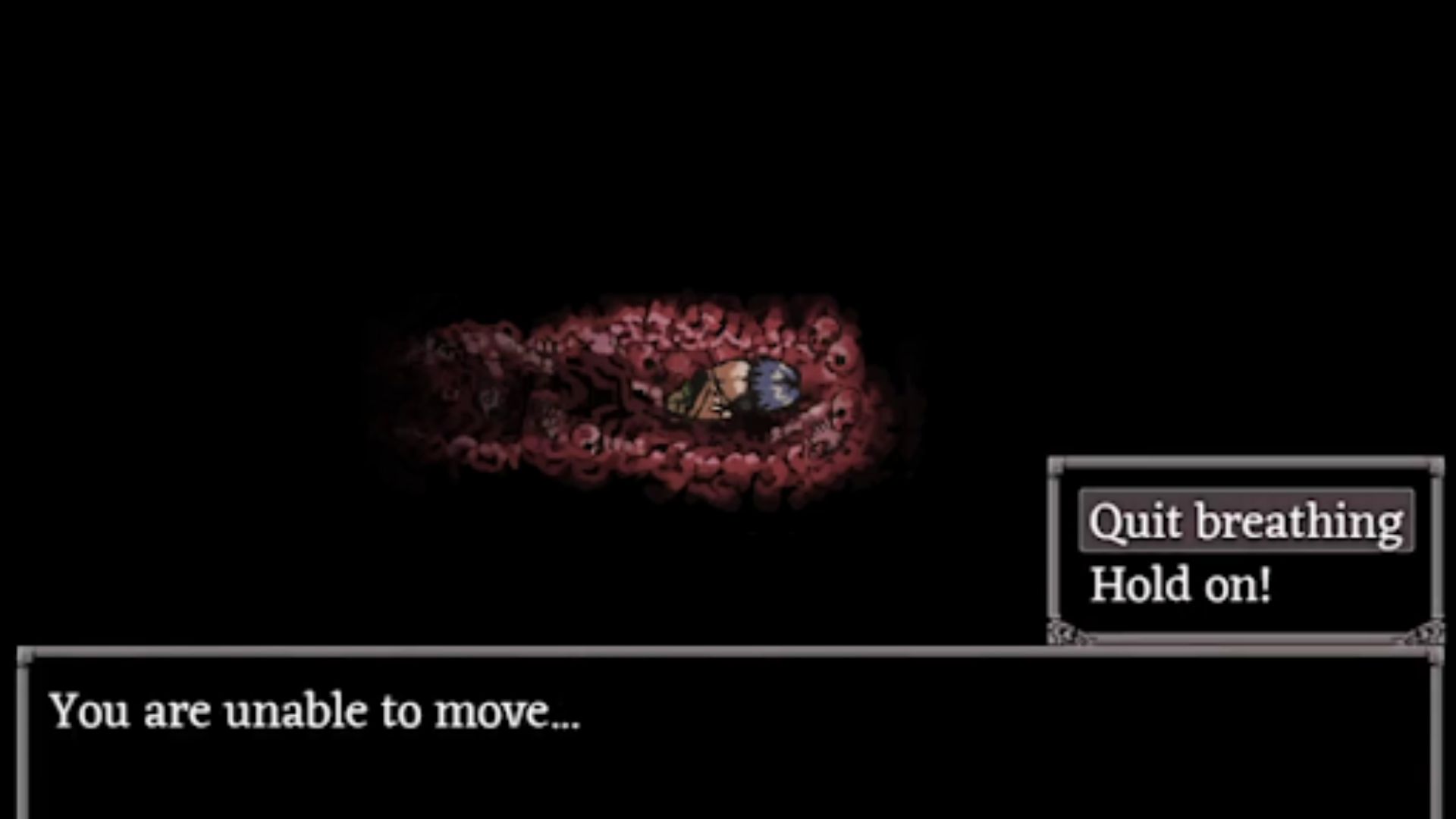

Fear and Hunger is an indie horror RPG that is infamous for its cruelty. From its grim art style to its severe difficulty, Fear and Hunger is a game that wants its players to suffer. No run of the game is complete without the characters being physically maimed and mentally tortured.

One of the core mechanics of Fear and Hunger is the severing of body parts. Instead of merely attacking an enemy, the player picks which body part they would like to cut off, or at least, attempt to. Some enemies even had more than four limbs, making battles even harder.

The twist in this game is that the enemies can also sever your body parts. If an enemy successfully cuts off one of your limbs, then that limb is simply gone. Taken to the extreme, a player character can potentially have all of their limbs amputated.

In that scenario, the game doesn’t end, even if you somehow survive the battle. The player, limbless, cannot move. They only have two options.

Hold on.

Or quit breathing.

Holding on does nothing. The only real decision is to quit breathing, which kicks the player back to the main menu.

You might be asking yourself, what was the point of the two options? One does nothing, and the other is a reskinned “Quit to Main Menu” button. The point of this endeavor is precisely the fact that it’s pointless. You are a helpless heap of meat, whose only two actions are to wait for death or make it come faster.

This horrific scenario reminds me of the 1938 novel by Dalton Trumbo titled Johnny Got His Gun. The book focuses on Joe Bonham, a World War I survivor who is left deaf, blind, mute, and without any of his limbs. Trapped in his own body, and with no real way to communicate to the outside world, Joe reminisces about the life he had and the horrors that brought him to his current state. In essence, he was already dead, but the world wasn’t letting him go.

Playable deaths are so morbid yet fascinating. The typical stereotype for video games is that of the power fantasy, an escape from reality. Even difficult video games such as Dark Souls or Ninja Gaiden, after a certain skill level is reached, become a satisfying underdog story. It’s empowering to overcome the difficulties a game throws at you, even if you’re battered and barely holding on by the end of it.

But the playable death turns that concept of control and empowerment on its head. Instead of feeling accomplished, the game puts the player in the ultimate state of powerlessness. When choosing, you made a mistake, and you have to face the consequences. The game essentially has you at its mercy, and the small measure of control it gives the player is to let you revel in what you have wrought upon yourself.

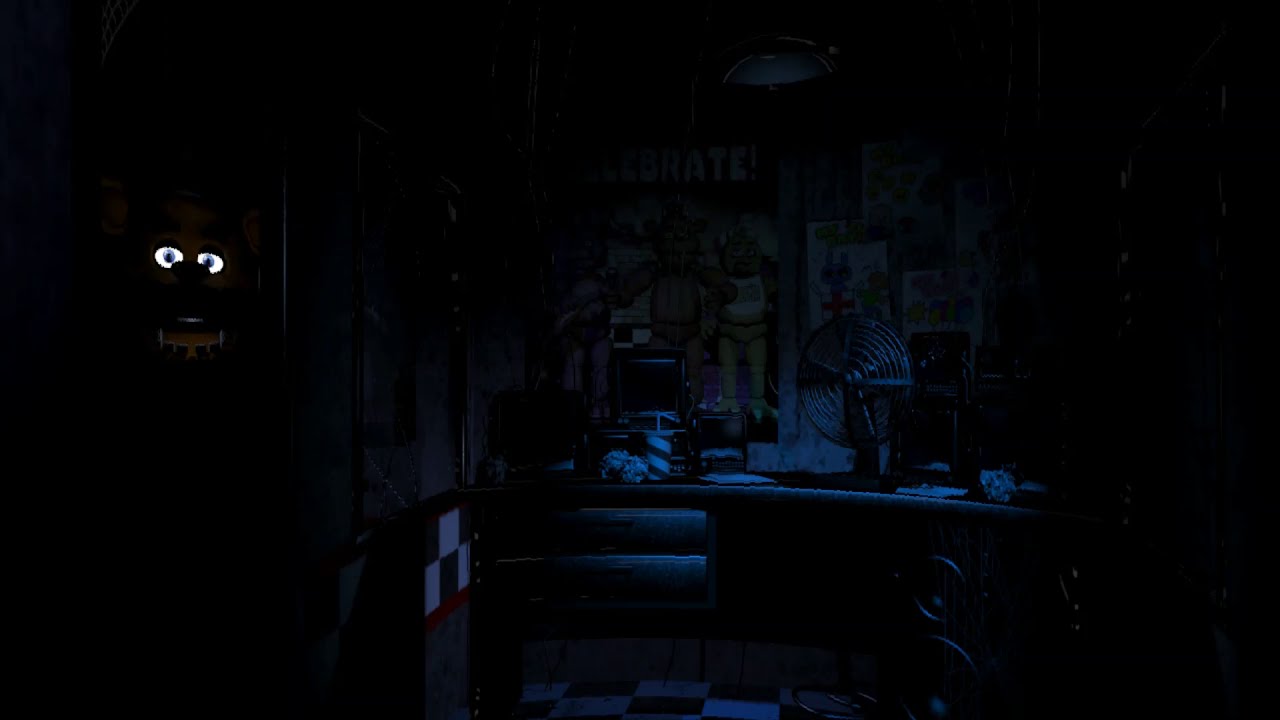

The very first Five Nights At Freddy’s game utilizes playable death quite effectively. It is a resource management game first and foremost, where the tiniest of mistakes could cost the player. One such mistake that many players make on their first night is keeping the doors closed.

After all, the game just told players that closed doors mean those creepy animatronics can’t get in. Unfortunately, the doors consume a lot of power, and without power, there are no doors. Once the power runs out, the doors jolt open and the player is left in darkness.

They can still look around or try and press things, but without power, everything in the office is now useless. A jingle plays as Freddy’s eyes glow through the doorway before the inevitable jumpscare death happens.

It would have been easy to make this a simple game over screen. However, the decision to give the player some control via their choices is a clever ruse. The player starts to think there’s something they can click that gets them out of the hole they dug for themselves. In doing so, playable deaths give the player the scariest thing of all.

Hope.

And therein lies the crux of why playable deaths are so effective. It’s not just about the helplessness. After all, traditional game over screens already leave the player helpless, removing their control over the game. The trick that playable deaths pull is making the player think they might not die.

And there are few games that perfected the build-up and execution of a playable death better than Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare.

Call of Duty 4 is considered by many to be the archetype of the modern first-person military shooter, boasting a story campaign full of action-packed missions and military espionage. It’s also probably the last game you expected to hear about in a horror essay, but one mission cements its place in the pantheon of playable deaths.

“Shock and Awe” seems to be the typical Call of Duty mission at first. The player takes on the role of Sgt. Paul Jackson, a one-man army who effortlessly mows through hundreds of enemies to find a tyrannical dictator’s hiding spot. Just as you seem to be closing in, the squad is informed that a nuke has been found in the midst of the city, prompting all U.S. military personnel within the city to evacuate.

Combat turns to panic as you struggle to save as many fellow soldiers as possible, with each radio message warning you of your proximity to the nuke’s radius. Finally, you rescue a downed pilot and ride the helicopter to safety.

But there’s just one problem.

There is no safety. It didn’t matter how many people you saved, how many enemies you killed, or how fast you completed the mission. The moment Sgt. Paul Jackson started the mission, but his fate was sealed.

In effect, the entire mission was a “Playable Death”, as there was nothing the player could do to change the mission’s outcome. And the player gets to experience the aftermath firsthand. In contrast to the hectic action of every mission so far, the player is dropped into the barely functional body of Sgt. Paul Jackson once more.

The city is bathed in a blood-red tint, and the mushroom cloud looms over the skyline. Jackson slowly and painfully crawls out of the helicopter, over scraps of debris and the dead bodies of the people he tried to save.

After a while, he can’t even move.

All he can do is hold on.

Or quit breathing.

What makes “Shock and Awe” so effective is the sharp contrast between everything before it and the franchise it happens to be in. Call of Duty wasn’t really a franchise about “losing” at that point. In fact, it’s built quite the reputation for itself as a game about military exceptionalism.

Making Sgt. Paul Jackson, a typical one-man army in these first-person shooters, a mere statistic among 30,000 other American deaths puts into perspective just how small you are. It ripped away the power fantasy and confronted the player with the reality of war.

Much like Sisyphus pushing a boulder up a hill, the terror isn’t the fall itself, but the knowledge that there’s nothing you can do to stop yourself from falling. Playable death is one of those unique video game things that makes me adore the medium. It simply can’t be replicated by other artworks, and I hope to find even more clever ways for video games to kill me in the future.

15 thoughts on “Press X To Die – How Playable Deaths Shatter the Illusion of Choice”