Provided by Duckenheimer

Public Memory: Crafting Analog Horror in Video Games

If you’ve injected yourself into any community on a social network, or stumbled down the wrong rabbit hole on TikTok or YouTube, there’s a good chance you’ve encountered a Creepypasta in some way or another. Short stories — better yet, poorly written forum posts with a jumpscare — detailing unsettling entities that want nothing more than to see you suffer, or search for the truth. Maybe you heard of the Tumblr account out there sharing videos that bordered on snuff films, or perhaps you were made aware of the Pokémon-related conspiracy that the song for Lavender Town incited self-harm in players; it’s all about a quick scare with thought behind it.

The thing about old-school Creepypastas is that, despite a dead-set philosophy of “what you remember but scarier and also murder,” there has to be a consistent showcase of confidence within the presentation of this specific brand of horror; the creator knowing full well they have you in the palm of their hands. Whether it’s the boogeymen antics of Slender Man’s original image, or the hundreds upon hundreds of SCP (Secure, Contain, Protect) entries, it’s about selling that fear, and it’s challenging to do without certain evidence. This is where “analog horror” steps in.

Yes, analog horror, a burgeoning new sub-genre that saw its birth on YouTube; the term itself was coined in late 2017 by the likes of Kris Straub while promoting their LOCAL-58 series. Since then, the term has been lovingly applied to the likes of “The Mandela Catalogue”, and Kane Pixels’ found-footage rendition of a post on 4chan’s paranormal board detailing something called “The Backrooms.” The term itself relates to the format of how these events are recorded: Scratchy VHS footage in the nature of family videos, public service announcements, or informational tapes detailing threats, procedures, or the secrets of an entity that’s no longer forgotten. Who recorded them? Who knows, they may be long gone, or maybe they wish they could forget what happened.

While the term may have only been recently coined, the type of horror synonymous with this analog movement has been around for almost as long as Creepypastas have. If you wanted the true progenitor of analog horror, you’d need to look at Troy Wagner’s seminal Marble Hornets series on YouTube, a large component in creating the current Slender Man mythos. A product now considered timeless with the current internet age, both Marble Hornets and the current crop of analog horror has thrived from the immediate discussion surrounding it. It bypassed the need for water-cooler conversation, you had a world of debate at your fingertips, for better or worse.

At the very least, it’s putting a new spin on the type of Creepypastas you’re used to. What analog horror entries like “The Walten Files” and “Gemini Home Entertainment” aspire to be was already achieved by the likes of infamous Creepypastas detailing lost media like “Suicidemouse.avi” and “Dead Bart (7G06).” That may seem like an absurd claim, of course, since it’s only through a retrospective eye that we see the latter options as silly, but back in the day? It was fertile ground, and not just for images of Squidward from SpongeBob Squarepants with “hyper-realistic eyes.” This was an oncoming wave of internet horror for an audience that — hell, at this point, 15 years ago — was sharing playground stories of this caliber. Untruthful they may have been, but we have always been storytellers as a societal collective.

It’s something that fuelled the ethos of horror author T.J. Lea, creator of “The Expressionless” Creepypasta. “Everyone [back then] had an experience with Goosebumps, or Courage the Cowardly Dog, and then they’ll go to the playground to talk about it”, T.J said, in an interview with Uppercut. “A child’s mind will twist and pervert what it sees, expanding from ear to ear. It’s the pathogenic concept of a scary idea.” T.J’s recollection of generalized nostalgia is exactly what makes analog horror work.

Like all cultural revivals made since the dawn of the 2010s, it’s about the aesthetic elevating the concept around it, and making sure the fear is built around the environment instead of vice versa. It’s not about famous kids show characters with bloodshot eyes anymore, or unlocking some secret theory about the sinister undertones of Shrek. Now it’s about unlocking original fear within and becoming scared of childhood fears you never knew you had. However, like the vaporwave genre, this revival is set back by being forced to play within its visual style.

There are only so many times you can rewind a VCR, and analog horror is, ironically, set back by its analog preference. It’s a rule set that may seem arbitrary, but can be bent somewhat significantly. For example, ARGs have helped elevate the popularity of The Walten Files, The Mandela Catalogue, and many others, to a confident height, but there’s still a layer of interactivity and immersion to breach. This, of course, is where video games come in.

In an industry that welcomes retro revivals with more than just open arms, it’s no wonder to see that the elements and philosophy of analog horror thrive in the video game landscape. Not only do these games allow for robust exploration of an area, an anomaly or otherwise, but they can also shift the goalposts of what can be considered analog horror while still retaining a core between the two mediums of film and game. After all, this is more than just a visual filter, this is about coming back to a time long lost.

Musing further, T.J. sees analog horror as recapturing something that we have done since we were cavemen: detailing threats to mystify and educate. “Humans have progressed so quickly in the past 20 years, that it’s left little thought for the stories made before social networks, and websites like IGN. Analog horror lends to this lost element by providing enough of a nostalgic twinge to fill in the gaps.” It’s that “filling in the gaps” part which is the most important crux for creators of this new movement: Not crafting a context for the participant, per se, but allowing them to create their own, going beyond participating, and becoming their own story-teller.

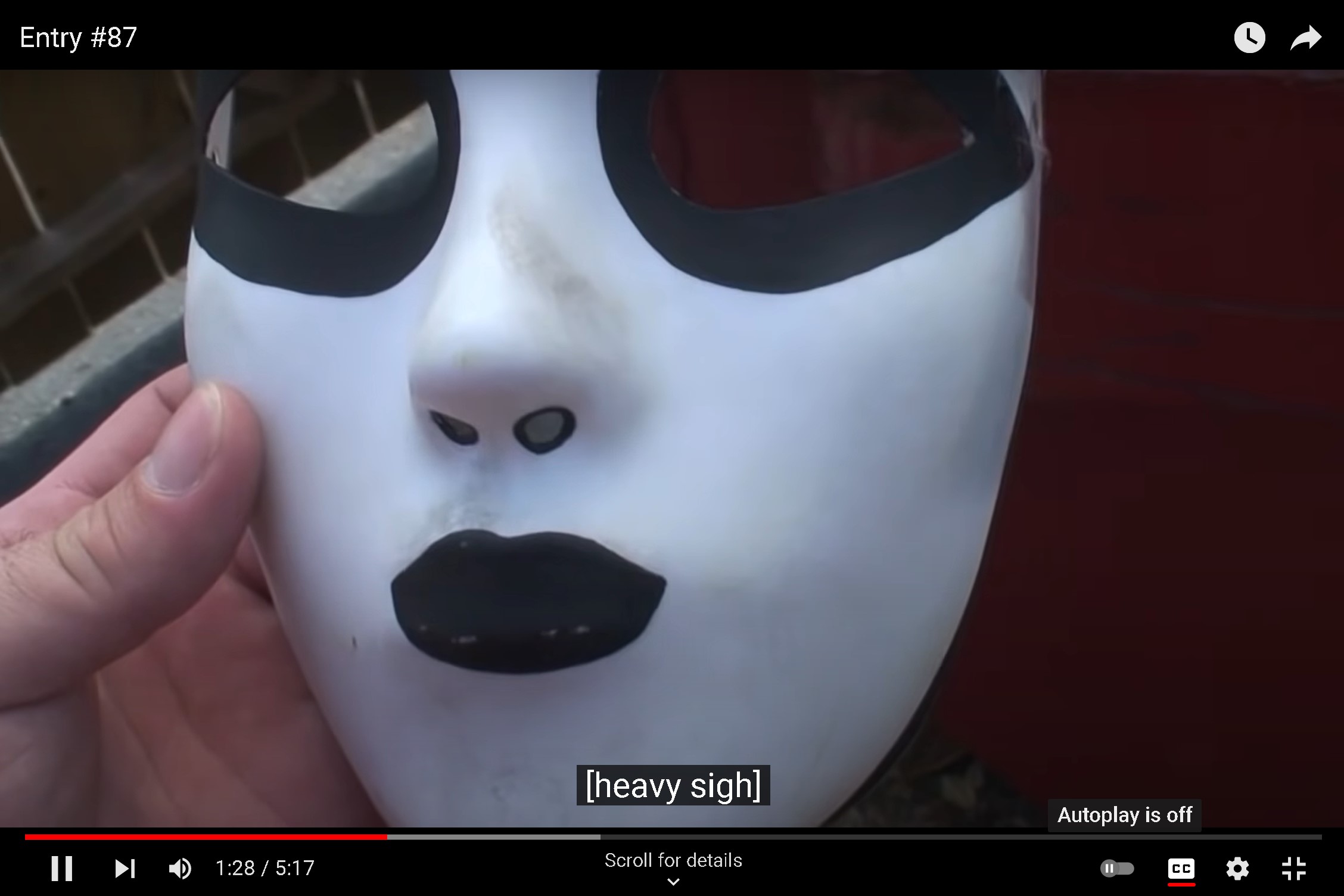

Take a look at something like Location Withheld, the commercial game debut from Texan developer Bryce Bucher. The player is immediately in charge of a short investigation into the surreal murders of several people with missing facial features at the time of death, and you’re treated to the kind of unsettling imagery analog horror is known for. Where the eyes, lips, and nose should be, there is now a smooth layer of untoned, unwrinkled flesh. Whatever’s caused this has haunted the player-character for some time.

Bucher has unabashedly cited analog horror as a main source of inspiration for Location Withheld, tying it in with his love of 90s adventure games. It’s the latter that has become a nostalgic breeding ground for the type of spotty narratives that analog horror adores, and while Location Withheld doesn’t directly subscribe to the more obvious elements, Bucher is aware of how the genre can mutate and shift about. When clarifying in an interview with Uppercut, Bucher stated, “If not [A VHS creation], then it is usually presented as some kind of alternate reality nonfiction.”

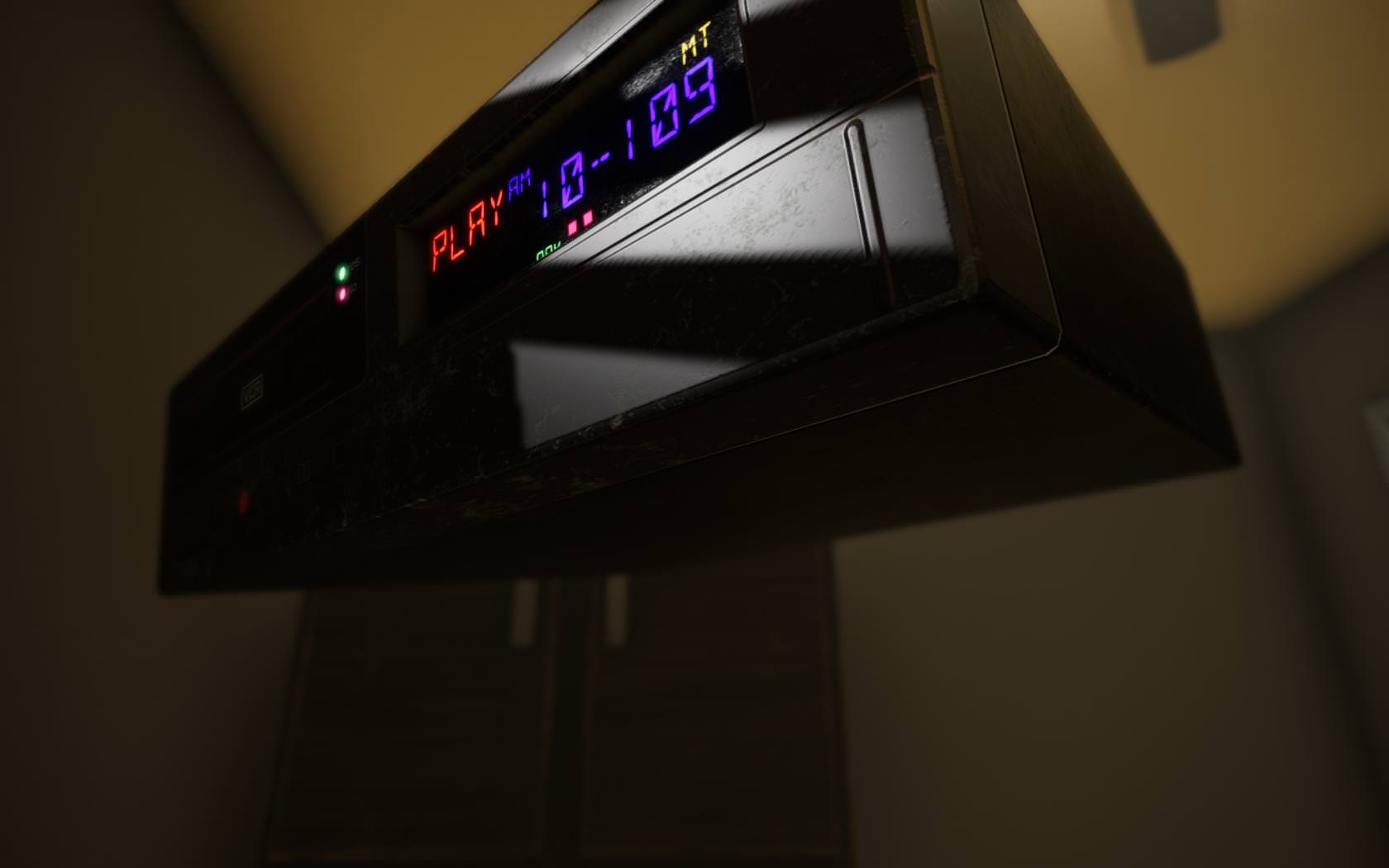

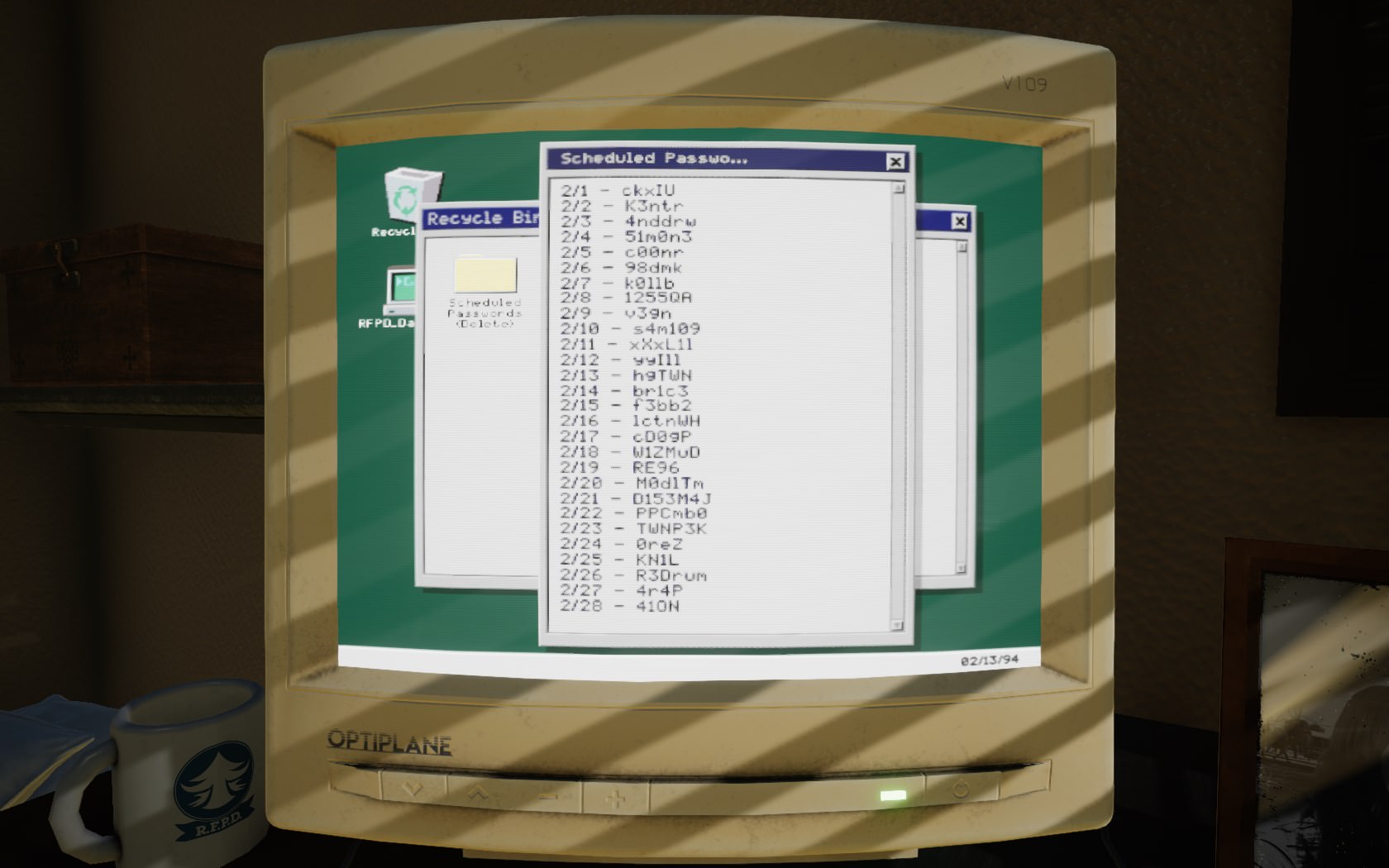

It’s a line of thinking that pushes something like 2000 Navidson Lane, developed by one-person team Duckenheimer. Taking the role of a freelancer doing odd jobs to make ends meet, you’re told to record footage of a house invested by an unknown person in order to make sure there’s no damage done inside. Upon entering, you’re immediately set off by the fact that the TV’s on… and there are unwashed dishes in the sink… and the hallways keep shifting into a labyrinthine state… it’s a bad do, basically.

Duckenheimer has stated that his main inspiration for 2000 Navidson Lane was the novel House of Leaves, released in 2000 by Mark Z. Danielewski. While the inspirations are worn heavily on the sleeve for Duckenheimer, the terror is ramped up rapidly, distancing itself from the novel’s often-debated horror elements. At the same time, it’s House of Leaves’ liminality (liminality in this context bearing similarities with the concept of the Uncanny Valley) which has been an unintentional inspiration for stuff like The Backrooms, and it’s something that Duckenheimer himself has enjoyed about the analog horror movement.

“Analog horror stories often don’t have clear premises or conclusions. It’s more about creating uncertainty and letting the audience fill in the gaps”, Duckenheimer said to me in regards to how they view this new sub-genre. When asked about his favorite entries, he said, “I do think the PSA and instructional type stuff is cool, and while there are some wicked sick monsters coming from this genre, I think it really excels in ‘documenting’ anomalous spaces.”

While 2000 Navidson Lane balances both prominent elements of this new movement, it’s the latter that it embraces with open arms, and rightfully so. It’s about a specific time and a specific place that formulates into an important moment to build upon. Whether it’s the player or the (usually) nameless character they occupy, it’s not about the destination, it’s the journey, and the sights you see along the way. If you want a game about a metaphorical and literal journey, take a look at Sylvio, a 2015 release from Swedish one-man team Stroboskop.

Created before analog horror got its name, Sylvio unintentionally became a progenitor of the movement in video game format, not by subscribing to its now-known values per se, but by implementing everything that we already know about the genre beyond its aesthetic. The atmosphere is thick with a heavy-set blood fog, the wind whines through dead trees, and you’re covering a tragedy that’s beyond what you’ll ever know. Your interviewees? The souls that were lost in a landslide, taking the lives of hundreds at a leisure resort in 1971.

Sylvio’s unique selling point comes from the use of EVP equipment utilized to interview ghosts in order to progress the plot, breaking ground in a way that is yet to be equaled. When I queried Stroboskop about what analog horror is to them, Stroboskop gave a passionate essay, stating that analog horror is, “… in my opinion, the strongest kind of horror, because nothing is [scarier] than what our minds can come up with.”

Stroboskop talks about the summers spent “… in the garden of our summer house, staring into the darkness”. He sees it as a means to an end to bridge the gap between what you can see and what you can’t see. “Your brain will try to make sense of it, and when it can’t, it will suspect the worst. That’s how our ancestors survived, I guess.” It’s that worst-case scenario line of thinking that drives home Sylvio’s general horror and its analog tendencies: Knowing full well that the imagination is far more powerful than what any designer can create.

Of course, you can still sometimes see what threatens the protagonist of Sylvio in gameplay, taking the form of giant plumes of black smoke that evolve into the shape of a featureless human. At the same time, Sylvio’s paranormal inspirations are largely untouched in an analog horror landscape, its ghost interactions propelling otherwise lackluster and below-average graphics. Despite this, its use of ambient lighting and sound design in quieter moments manages to do what AAA games can rarely achieve with all the money and hyper-realistic graphics in the world: dread.

That isn’t to dismiss the medium higher-budget tendencies entirely. Take a look at what Resident Evil 7 was able to achieve with the VHS gameplay interludes of “Derelict House Footage” and “Mia.” Is this the future of analog horror though? Not necessarily. Resident Evil 7 plays with a lot of these found-footage tropes but fails to find the footing beyond cheap thrills. While these cheap thrills fall in line with analog horror’s rather digestible offerings on YouTube and video games, the keyword is nuance, and Resident Evil is anything but nuanced.

While discussing this direction forward with several developers, all had similar ideas that varied slightly from the root. For example, both Duckenheimer and Stroboskop have expressed acknowledgment and concern, respectively, for the younger generations’ lack of attachment to the aesthetic of VHS, the former noting, “I see a lot of YouTube comments on “old” music about how someone is confused that they can somehow miss a time that they didn’t live through.”

Is there a solution for this? Potentially. Given the restriction of these aesthetics, Duckenheimer sees expansion not in emulating the visuals, but in the generation itself. “Maybe the next step for analog horror isn’t just imitating analog media, but more a broader type of ‘halcyon horror’ for everyone.” What does this mean, exactly? Well, it’s rather dystopic in implication, the real world we inhabit seeing us yearn for simpler times. Whether it’s in age, environments, or otherwise, what’s happening in our reality is disturbing. The term “doomscrolling” has become synonymous with the simple act of just being on Twitter, or turning on the radio for a moment.

In all of the examples mentioned in this piece, the old-school Creepypastas, the analog horror videos, and the games pushing it forward in their respective medium, one key element tying them together has been the payoff. Jeff the Killer’s accompanying image, demanding that you go to sleep. The Mandela Catalogue’s examples of an “Alternate”. 2000 Navidson Lane’s jumpscare. It’s the haunted house ride’s finale, and an encore is rarely necessary. You don’t need to shoot for the stars when the ceiling’s in the way, you’re in a perfectly crafted space that doesn’t need expanding.

If you wanna see the future of what a movement like this involves, look no further than Iron Lung, David Szymanski’s latest and most horrific experience. While not directly tied into the analog horror movement, it bears resemblance to many of the themes present, elevating the ideas, philosophies, and narrative qualities you’d usually see. A sinister universe, a threat bigger than what you can humanly grasp, and an event you can barely comprehend. It bleeds nihilism through and through, while also carving originality into every avenue of horror you can place it under.

You play as a prisoner, one of the few humans left alive after an event known as “The Quiet Rapture” caused almost every planet and star to disappear entirely from the known universe. In a vantablack galaxy, the only survivors are the ones populating quickly-depleting space stations, running out of resources, parts, and hope. After one space station comes across a semi-mythical “Blood Ocean”, the potential for resources is high. In exchange for your freedom, you’re tasked with taking pictures in a window-less submarine, while something lurks underneath the red sea with you.

Iron Lung has it all: Perfect pacing structured around an hour-long experience, narrative stakes placed at a fever pitch (which, incidentally, share some similarities with the Twitter account/ARG @TheSunVanished), and sound design which towers above all. Inspired by the works of lesser-known DOOM soundtrack alumni Aubrey Hodges, it was this sensory deprivation experience that drives home almost all of Szymanski’s horror, both in his game development work, and his musical endeavors.

“The idea of basing horror in glimpses of things that can’t be completely grasped or understood is something that’s driven my games from the beginning for sure”, Szymanski said to me, in regards to his horror inspirations. While there is a threat in Iron Lung that the player can experience, it’s more about what you can’t and won’t see that becomes scarier; darkness there, nothing else. The retro aesthetic that’s been applied to a lot of Szymanski’s games, it’s an inspiration that derives from a lot of what analog horror tends to generate.

“[With Iron Lung], I played around with some VHS stuff, and ended up feeling that a bit of chroma blur gave the overall image this aged grimy feeling that fit well with the vibe I wanted to capture.” He then revealed that “for someone my age, it puts me in mind of old PBS shows, home videos, etc… things from my childhood… It just immediately communicated to my brain that what I was looking at was old, probably cheap, maybe musty… all things I wanted the player to feel about Iron Lung.”

As for the actual graphical elements of Iron Lung, Szymanski acknowledged some of the haphazard elements of the texture work; visible seams, unsmoothed bends in pipes, examples of inaccuracies, but not laziness. “I’ve always thought of game visuals more like painting than anything else… [not literally], but in a sort of “feel” sense — if Iron Lung were a painting I can imagine I’d have done it with aggressive, violent strokes: sliced the image out from the canvas”, Szymanski stated.

It fits right in line not just with the fate of the player-character, but the fate of the universe in general, Szymanski describing it as “… a nasty ugly piece of abstract expressionism that’s implying a nasty ugly hunk of iron where you’re going to suffer and ultimately die. You’re in this situation you can barely grasp, in this universe we can barely imagine, with things you can barely see or comprehend just outside your view.”

That is the core concept of analog horror, right there. It’s not just about finding footage of a hopeless sap and their last moment, but inspecting that small tidbit of the timeline where, for one moment in time, you’re the most important person in the universe. You’ve stumbled across footage of an evil that’s traveled years, centuries, eons to get here, and your only evidence blurs out the importance. That sudden impact of insanity brings a curt end to a world-changing event.

Analog horror, as an aesthetic or visual style, is nothing more than a perpetual name tag, only now becoming infected with a thin layer of cynicism. What you know of and what you’ve seen on YouTube and TikTok is only scratching the surface of one of the most cutting edge movements that the horror landscape has ever seen. Only by shifting these goalposts will it be allowed. It’s only by allowing new creatives with their original ideas to push the boundaries of this new sub-genre that we will see it grow to be an even bigger powerhouse within the horror medium, potentially one day eclipsing other sub-genres like splatterpunk, cosmic, or folk-based horror. Because it’s not just about looking into the past. It’s about the future, and the fate we create.

If you like what we do here at Uppercut, consider supporting us on Patreon. Supporters at the $5+ tiers get access to written content early.

1 thought on “Public Memory: Crafting Analog Horror in Video Games”