13 Sentinels: Aegis Rim-I Could Use A Love Story

Mary J. Blige once sang “all I really want is to be happy and to find a love that’s mine, it would be so sweet.” It’s a simple plea, and one I find myself relying on to get through life’s darkest days. At the end of the day, I’m a complete sap. I fawn at the idea of being gifted flowers (unexpectedly, of course) and being treated like I’m somebody’s somebody. But mostly I’m entranced with the idea of an equitable relationship–a launching pad for mutual growth and a challenge and journey in its own right.

For that reason, I don’t always click with dating sims, and even less often in games with romance options. For one, where’s the drama? If I go into, say, Persona 5 or Dragon Age: Inquisition knowing there’s a colorful array of options waiting for my go ahead, I immediately get bored. For one, as a gay gamer the connect between me and my bevy of options is often tenuous at best. More than that, though, romance is all about the surprise; my own relationship was a sudden windfall. One night, before Christmas Eve, I received a Tinder message from a guy I’d matched with six months ago yet had never spoken to. He had blue, almond-shaped eyes, brighter than my own, and a permanently sullen expression. I tend not to trust people that smile in their pictures, maybe because I don’t in my own.

At the top of the year, my boyfriend and I moved in with each other. This brought its own set of challenges that were only exacerbated in lockdown. Over the last nine months, we’ve navigated our own developing political consciousnesses in rapidity, while also dealing with depression, exhaustion, and our own fears of the future. This year taught me just how essential love is for me, no matter what form it comes in—it’s a balancing force, and a subject that’s been captured to varying degrees in media in every epoch since humans began roaming the earth.

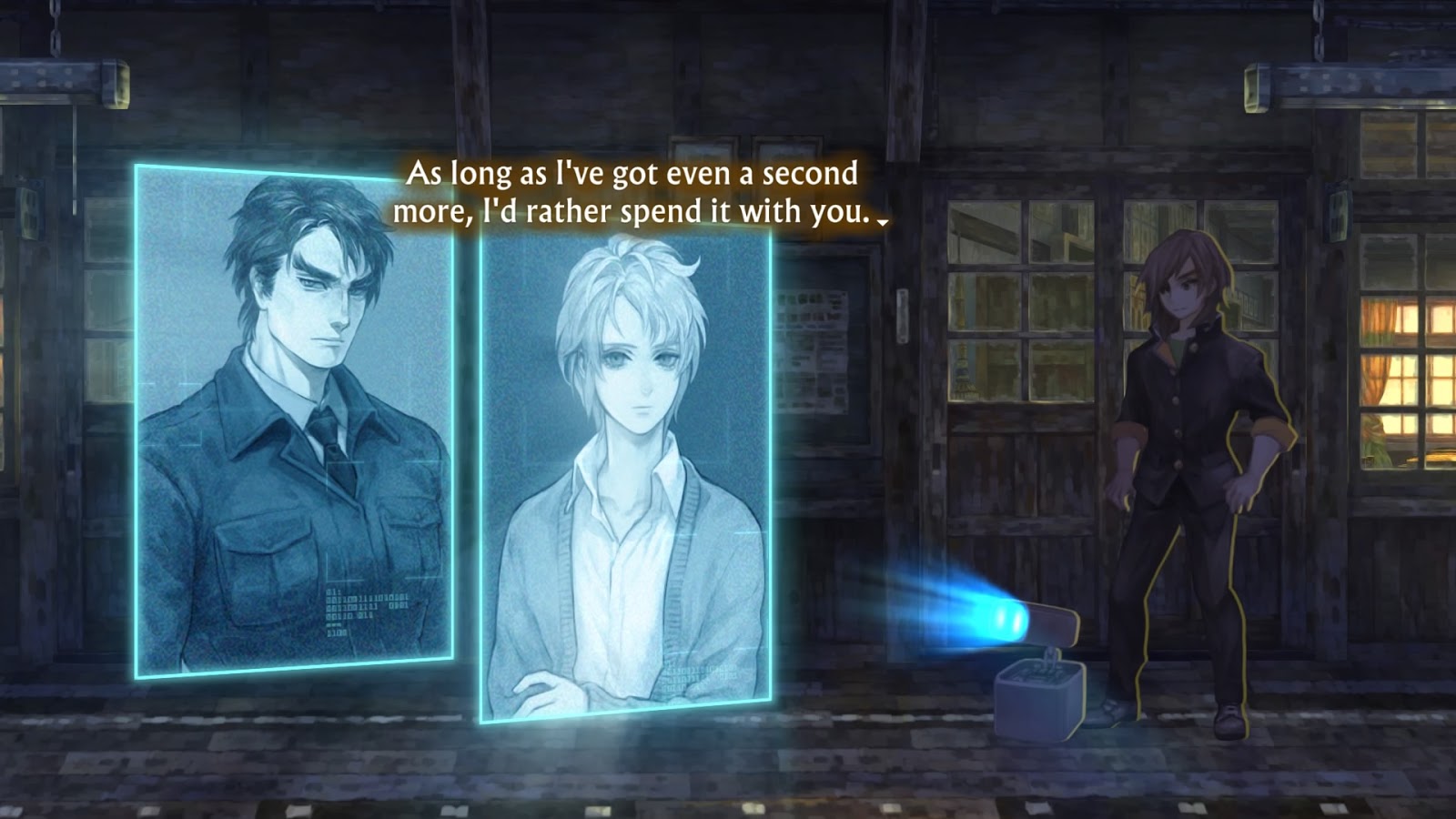

Video game romances are often trite because the purpose they serve is an obligatory one. We’re often meant to identify with one character, sometimes overly so, so that we might project our own feelings onto them when choosing a partner. However, 13 Sentinels: Aegis Rim is a bit more subtle in its approach to love. In 13 Sentinels: Aegis Rim, you play as 13 teenage mech pilots and follow their individual stories leading up to their final battle against a kaiju invasion. When I say final, I mean final; the livelihood of the planet’s at stake here, and they can’t afford to lose. Oh and also, it’s the mid-’80s.

Such a high stakes set-up is the perfect scenario for intimate connections. Through multiple perspectives, we experience several love stories each in different stages of gestation. Iori, a classic heroine with a floral barrette and weird, prophetic dreams, bumps into Ei as she’s running to school late and she’s immediately infatuated with him. Meanwhile, Ei’s story takes place a little further along, with a Memento-esque opening. After waking up with amnesia next to the corpse of Iori’s school nurse, he attempts to retrace his steps using just the clues he found at the crime scene, which inevitably leads him back to Iori, who, now that time has passed, is dangerously enamored with him. Their narratives intertwine uniquely, and imply things about each other’s distant pasts and hazy futures.

This prescient passion is a factor in nearly every character’s romance, of which there are several. Megumi toils with the moral conundrum of harming her friends to restore the memories of the boy she loves, Juro. From Juro’s eyes, she’s a pushy home invader blackmailing him in order to crash at his house. Natsuno, a girl on the track team who travels back in time to her town during the Pacific War, meets a young child soldier named Miura who accidentally follows her to the ‘80s after his town’s ravaged by kaiju, only to find it westernized and foreign.

Everywhere you turn in 13 Sentinels’ vision of the ‘80s, you hit a wall. Crushed by the trauma of the distant past and living in fear of the near future, the game presents a world where hundreds of closed systems stymie the livelihood of modern civilization. The only liberatory force in their lives, then, comes from within—an irrepressible urge to connect, and an unfaltering dedication to one another. All this is heralded by a lovely Showa era J-Pop theme, a gem that playfully alludes to Macross while serving as an emotional core for Shu, who becomes embroiled with the idol who sings it.

Playing 13 Sentinels, I couldn’t help but connect the game’s story to our daily troubles today, partly because the game occasionally flashes forward to a ravaged 2025. Here, in 2020, thinking about what the world might look like in 5 years can feel like peeking into a doomed future. That’s one more presidential election away. More immediately, we’re a month away from going into 2021 with an untamed virus still snaking its way through the globe. Nineteen of the twenty warmest years on record have occurred since the turn of the millennium. Late stage capitalism continues pushing workers to the periphery and disenfranchised laborers such as trans people, sex workers, and people of color struggle to find alternative ways to participate outside of our monopolized economy. The threat of kaiju could easily be substituted with a biological weapon, a human war, or the covert menace of a megacorporation and it would manage to feel just as world threatening as it does now.

But 13 Sentinels makes a pointed decision to go with strange, mechanical monsters. Since the genesis of kaiju media, they’ve often been equated to the fears and trauma post-war Japan dealt with after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In this way, 13 Sentinels isn’t quite a cold war story, but instead a story about a society with amnesia. The titular pilots discuss their strange dreams where older versions of themselves clash with robots and each other alike in futuristic cityscapes. But what if these dreams weren’t of the future, but a forgotten past?

When time converges into a single moment, the only thing the pilots have left is themselves. And without the passion that glues them together, only destruction is assured. Another wave of personal, national, and global amnesia looms just out of reach, threatening to erase the lives the pilots have built in the ‘80s, whether they were born then or had to seek refuge after their own time period collapsed.

The capacity the kids have for empathy for the others displaced in time reminds me a lot of my own queer family. Robbed of several choices and opportunities, we cling to the people who traipse into our lives unwittingly. This is another joy of life’s many surprises. What binds us together is our foresight. Much like the cast of 13 Sentinels, we see events of apocalyptic proportions just over the horizon. Millions of people realized fractures in American society’s treatment of people of color, immigrants, and other systemically persecuted people as if it just began this year. But for the people suffering under America’s dark practices, oppression has no origin point. Instead, it swoops in at many points of history simultaneously, then erases itself as if it never happened.

For that reason, 13 Sentinels being a story of love was one I needed this year. The people that love you are the ones who preserve your own history, and only in remembering can we hope to make a new world and leave behind all the heartache. The game forsakes any conduit for its players to project themselves and instead bursts with a pervasive, intimate gentleness. 13 Sentinels gave me hope that everyone will find a love so sweet one day.