Saint Maker Reckons with Religious Trauma, In-Game and In Real Life

[Warning: Some spoilers and discussion of religious abuse ahead.]

Holy Week – the holiest week of the entire year – rolled in by the time I completed Yangyang Mobile‘s Saint Maker. From attending masses to participating in processions, the faithful are encouraged to observe Lenten traditions as a way of atoning for their sins. Yet, amidst the solemnity of the season, I found myself grappling with the darker aspects of religious life — forced participation at church services, discrimination against the LGBTQ+ community, religious abuse, and so on. Saint Maker leaves you with a bone-chilling reminder that faith can be destructive when taken to the extremes, not only to others in your vicinity but to yourself, most especially.

Saint Maker released for the Nintendo Switch on March 22, 2023, just a week away from the last week of Lent. It’s quite a gutsy move for an indie game studio based in the Philippines, where 78.8% of the household population identifies as Roman Catholic as of 2020.

While it’s unclear whether the timing of release was intentional or purely coincidental, religious influence is apparent across the game’s development. Saint Maker is a visual novel about two teenage girls, Holly and Gabby, sent away to a religious recollection with Adira, a troubled, increasingly violent nun.

“Growing up Catholic, I’ve known people who have experienced abuse by religious parents or religious adults… I tried my best to channel these experiences into the game’s story,” Carlos Valdes, Saint Maker’s writer told Uppercut.

Illusion of Choice

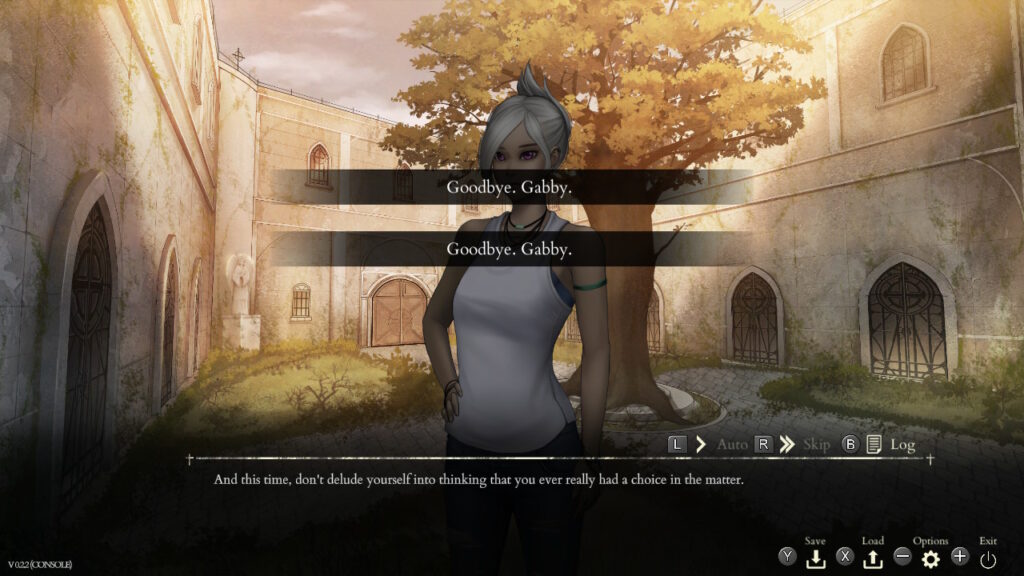

A standout game mechanic in Saint Maker is its rigged dialogue choices. It’s a trademark characteristic for visual novels to have multiple pathways and endings influenced by the player’s decision-making. But whatever you choose, the outcome remains the same in Saint Maker.

Saint Maker toys with the illusion of choice, seemingly giving players the chance to turn the tides only for it to be for naught. Oftentimes, the characters even question the decisions I make for them, opting to take the actions I didn’t want them to in the first place — actions that would clearly lead them to ruin.

This loss of agency over the storyline creates a sense of frustration that many players are not familiar with in the visual novel genre. A GameGrin review even said, “The one thing I love most about visual novels is that you can choose the way your story plays out. Unfortunately, it does seem like Yangyang Mobile took that choice away, and that did change the way I enjoyed the gameplay.”

At just 60,000 words and 4-6 hours of estimated gameplay, Saint Maker was intentionally scoped to have a short-form story with fewer branching pathways. The dialogue choices were retained to reflect Holly and Adira’s deteriorating mental state in the most hard-hitting, guttural way possible.

“Holly herself feels trapped, not just in her home life, but trapped inside her own head as well. Our intention was to have these choices serve as a way to evoke how these intrusive voices can shape a person and how torturous it can be to live in that state of mind. Holly feels like she was never given the agency of choice in her life, and so neither do we,” Valdes explained.

I find this illusion of choice to be an unnerving parallel to very real mental states and lived experiences, reinforcing the horror of the game. Many people in extremely devout households or institutions, just like Holly, feel like they have a choice but have no actual autonomy. Think about parents who claim to love their child no matter what, but when they come out as queer, open up about self-harm, or read fantasy novels, they become “sinful”. These instances, both in-game and in real life, seem to suggest you’re only allowed to make choices if they align with what’s wrong and what’s right in the realm of one particular faith. Nothing’s scarier than that.

‘Too Real’ Characters

Saint Maker centers around three characters, Holly, Gabby, and Adira, each with their own internal demons and religious influences. What’s engaging about Saint Maker is the characters were drawn from real experiences.

Holly was designed to embody people who were trapped in overtly religious households, people who told themselves that everything was okay even when it clearly wasn’t. Carlos said, “Think of [her as] a girl who’d feverishly pray every night — not due to genuine faith, but fear.” This character rings truer when you consider that 74% of Filipino parents admit to using corporal punishment and 82% resolve to verbal or emotional punishment.

Gabby portrays people who are already aware of the dangers that ill-practiced faith can bring, but are still struggling to get out. She also embodies members of the LGBTQIA+ community who grow up in religious spaces that actively discriminate against them. To date, there is still no LGBTQ anti-discrimination law in the Philippines, and the bill for it was filed 23 years ago.

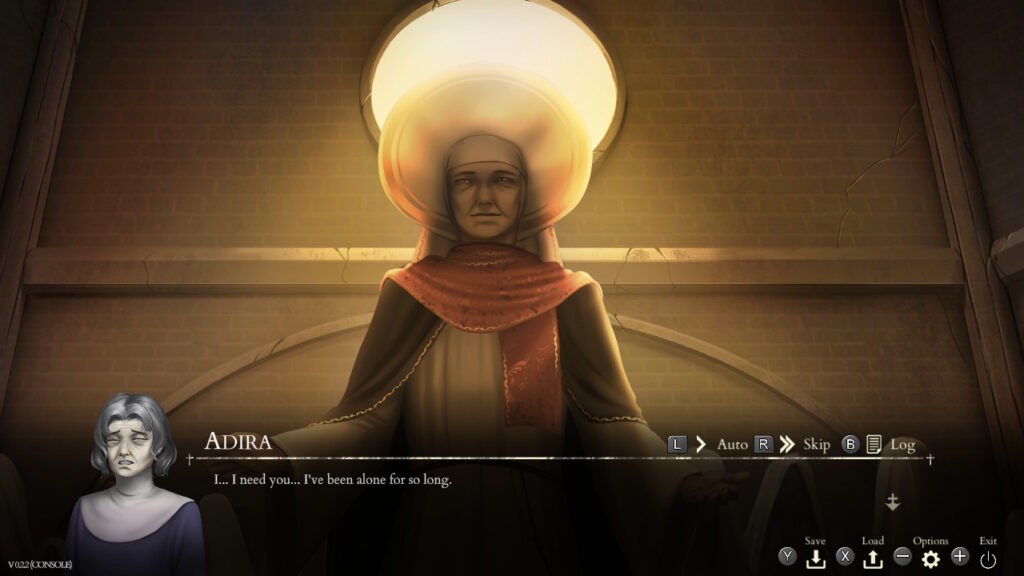

Adira is a depiction of those who have spent so much of their lives in religious abuse and indoctrination that they themselves end up perpetuating that cycle. She uses her faith to negatively cope with grief, guilt, and death — essentially losing her sense of self and twisting her faith in the process.

“A lot of these characters were drawn from personal experiences and from the experiences of others,” Carlos confirmed.

And these experiences appear to be widespread, at least in the Philippines. Like Gabby, I have queer friends discriminated against for their identity. Like Holly, I’ve come across people who gaslight themselves to avoid upsetting religious leaders. I even see those very leaders on the news who perpetuate a cycle of religious abuse, just like Adira. The game hits home, becoming not just a visual novel I read through a Switch, but a horror story reminiscent of realities often left hidden and unsaid.

Metaphor of Statues

Saint Maker’s themes can be encapsulated in the metaphor of statues.

Prevalent in the game are statues of Saints. Cracked, whole, decaying, moving. Adira holds an obsession with keeping these statues in pristine condition. She seals up the cracks and sands away the impurities in an attempt to restore it to a perfect state. The Idelorian Order, which Adira is part of, does the same to the young girls who enter their convent—they seal up their “sins” and sand away who they are, from Holly’s love for fantasy novels to Gabby’s queerness, and even Adira’s kindness in the pursuit of sculpting girls worthy of being Saints.

Saint Maker is ultimately a study of personal identity and how religious trauma can erase it to a point where you can no longer recognize yourself. It’s finding real life reflected in the confines of the visual novel, clicking at elusive choices, and staring back at characters that mirror stark realities. It is a game that, while unsettling, provides a necessary reflection on the darker aspects of religious life and the illusion of choice that many of us face.

If you like what we do here at Uppercut, consider supporting us on Patreon. Supporters at the $5+ tiers get access to written content early.

1 thought on “Saint Maker Reckons with Religious Trauma, In-Game and In Real Life”