Westwood’s Blade Runner Returns to a Generation Headed Towards Its Future

There lies an interesting and ironic theme about transhumanism and the nature of consciousness that can only work in a game based on the cult 1982 sci-fi classic Blade Runner.

The PC title of the same name released in 1997 by Westwood Studios puts players in control of another replicant hunter named Ray McCoy who’s working on his own case in the same timeline and universe of the 1982 Ridley Scott film. There are references to Deckard, the main character of the movie starring Harrison Ford, whose paths cross a couple of times even with some of the same characters played by the actors reprising their roles.

The spirit of the game that’s recently been re-released on digital stores like Steam and GOG.com courtesy of ScummVM doesn’t just come from the nostalgia trip it provides. The true trip takes you down a much deeper rabbit hole. The film and the game that are originally based on the short story Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? by Philip K. Dick raise some deep, meaningful questions about the limits and definitions of existence.

Blade Runner looks like it is just a detective story on the surface but the true puzzle prompts questions that go way beyond the usual “Whodunit?” variety. The game’s tone, story and style also asks questions like how do we truly know we’re awake or alive and how do we know we are the ones in control.

Could we just be pixelated pawns in someone else’s adventure game?

“It was never lost on me the irony of a person controlling this character and moving them about in a way that was very robotic and commanding,” says Blade Runner’s director Joe Kucan. “I will click on this area and this character would go there. That’s what happens in adventure games anyway but the irony in this particular game wasn’t lost on me because they are nine possible solutions or endings and one of the fun things about the game was there was always some doubt.”

Westwood’s Blade Runner game was a philosophical and psychological triumph that uttered one of the last hurrah’s of the ‘90s adventure game genre. The game had a malleable storyline that could reach one of nine different endings depending on the decisions the player makes for McCoy that not only revealed his cases’ culprits but also the very identity of the characters.

“It’s easy when you look around now at the landscape and see a ton of games that are playing with that kind of stuff but back then, that was not as common,” says David Leary who worked as the lead designer for Blade Runner along with Jim Walls and wrote the game with screenwriter David Yorkin. “It just kind of occupies this funny, little, middle transition period in the game from a linear point and click adventures to the landscape of other types of games that are out there today.”

Kucan and his team helped make Westwood Studios of Las Vegas, Nev. one of the most popular PC gaming studios thanks to the massive success of the Command & Conquer series (players will recognize Kucan as the nefarious villain Kane) that blended acting and storytelling with complex battle strategies. They soon had their eyes on an adventure game concept for a Blade Runner game and reached out to its executive producer Bud Yorkin. Kucan says they convinced Yorkin and his team to let them make it when they made a digital re-rendering of the breathtaking shot of a spinner speeding past a massive video billboard of a Japanese geisha promising comfort to a desolate and dark landscape.

David Yorkin who is Bud’s son and helped write the game with Leary says they had several offers to do a Blade Runner video game in the years following the film’s release. The original Blade Runner built up a cult following years after its less than stellar box office release. Fans who became game designers threw out several concepts for a video game but Westwood won the rights because Yorkin says they offered the deepest and most unique concept beyond mindless shooting and empty action.

“What they did was something that really felt fresh and well done and they had a passion for it,” Yorkin says. “They were real Blade Runner geeks and so I think that’s what everyone really responded to. They were the right guys to do it.”

Yorkin who had never written a game studied the Blade Runner film and its many director’s cuts since the film’s initial release in 1982. He put together an 80-page screenplay in which another blade runner named McCoy tracked down a series of replicants following a series of grisly killing at an exotic replicated animal store through future LA’s seedy underbelly. Leary was also very familiar with the bleak world of Blade Runner and fleshed out the script to fit the narrative of a game and construct a changing story that followed different paths while Yorkin polished the dialogue.

“A lot of the team are veterans of the Kyrandia series, which were some classic point and click adventure games from the Sierra model,” Leary says. “They understood that type of game pretty well and the question was how to make that look fantastic so that was when they started to build the new visual engine.”

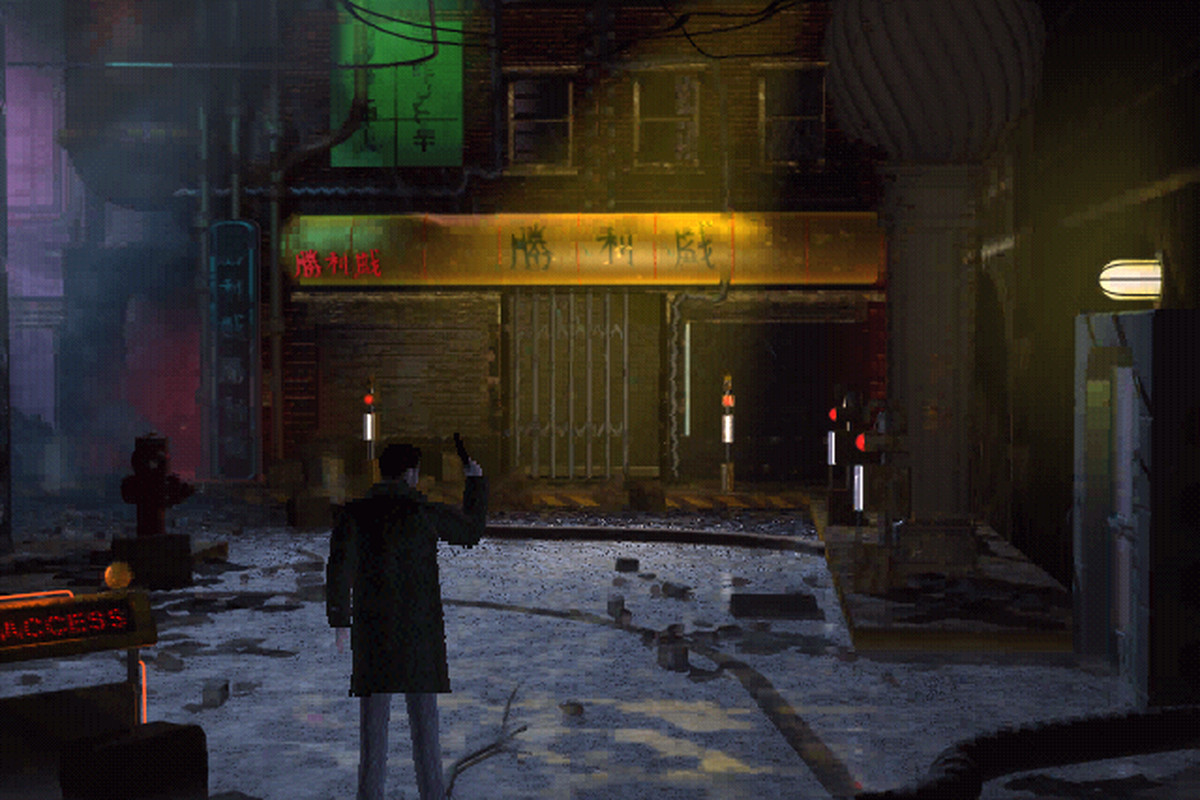

The game’s voxel engine could let the game render three-dimensional characters and scenes that will further immerse players as they traverse the bleak and stunning world of the future while “the frame rates wouldn’t crash the system,” Kucan says.

“It let us do what we needed to do,” Kucan adds. “The design team took an extensive tour of Los Angeles where the movie was actually shot. They visited the old hotel industrial park and a number of places in Chinatown where the original designers looked at and the concept art that came from the film. It wasn’t just a build based on locations from the movie but the actual locations.”

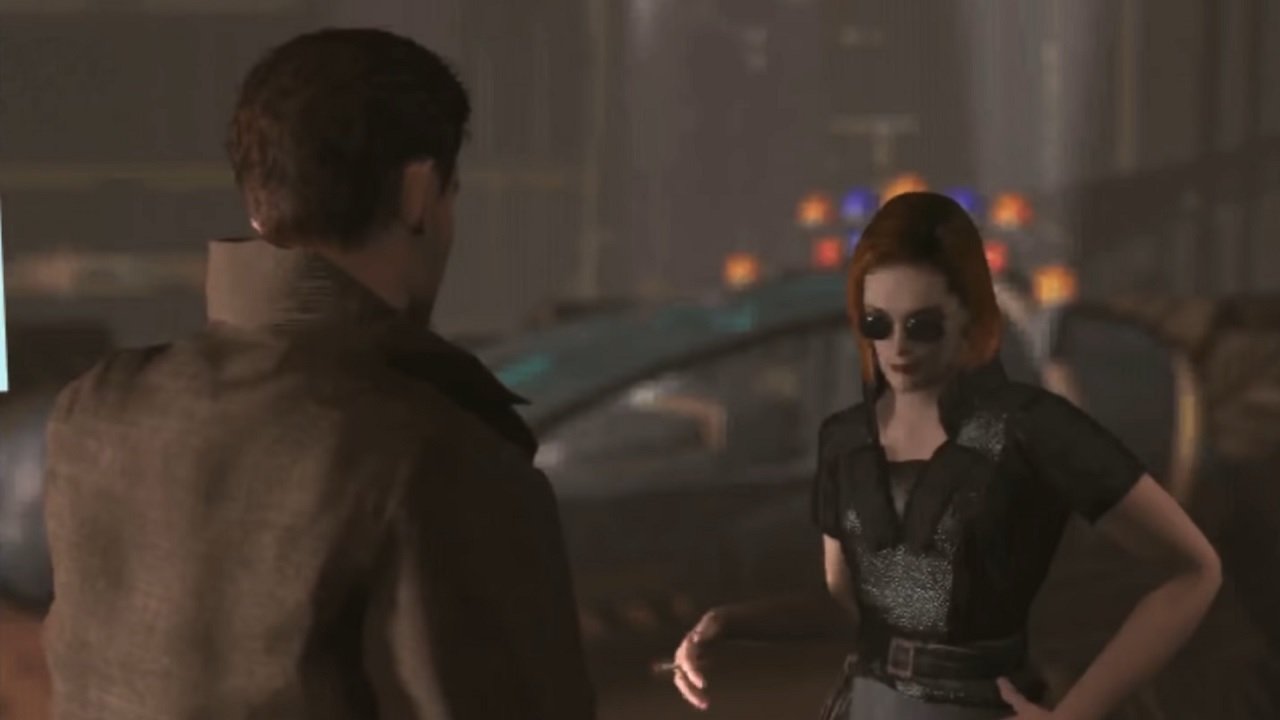

Kucan and his team also knew long before they made the pitch that Harrison Ford wouldn’t come on board but they were able to get some members of the film’s original cast like Sean Young, James Hong, William Sanderson and Joe Terkel to reprise their respective roles. The game had an even deeper roster of characters than the movie and not only required a new actor to play the main character but a wide variety of actors that includes revered character actors like Vincent Schiavelli and Michael McShane and future household names such as Jeff Garlin, Pauley Perrette and Stephen Root.

“I made some crack about how I was going to make his career like Stephen, we’re gonna make you famous,” Kucan says with a laugh. “He says, ‘You know what’s going to make me famous? I’m doing this little animated show called King of the Hill’ and I’m like OK, I’ll be sure to look that up.”

Screen, stage and voice actor Mark Benninghofen scored the job of voicing the game’s central character McCoy, a similar persona to Deckard who’s also questioning the nature and morals of his job and even his own existence. His performance required a mix of deep emotions punctuated by swift action sounds.

“It was five days of being the character and moving you through the narrative of the game like should we go or should we stay and I’m not sure what to do, that sort of thing,” Benninghofen says. “There there was a dead body call for action stuff where you would literally do the sounds of being punched in the gut, punched in the jaw, knifed in the shoulder, thrown down the stairs, kicked in the face. Basically what I did was I threw my 36-year-old ass around the studio.”

The team also captured the character’s look and movements from real life models before motion capture technology became a necessity for game scenes.

“We had to create these characters using skin texture so I remember a steady parade of Westwood employees coming through the door and standing on the turntable and being photographed in 360-degree stages in order to pull the textures off their skin to create these characters,” Kucan says. “So a lot of those characters if you were to look at them in super high definition, you would see the entire staff of Westwood Studios.”

The combination of story and scenes created a dark, oppresive atmosphere of an overcrowded Los Angeles where life is dominated by corporations and survival and safety seem to be in short supply.

“Part of the goal is to hit the mood and feel of the movie but to make it feel like we were telling a different story in that universe and I think we did a pretty good job on that stuff,” Leary says. “It’s a huge credit to the team just for hitting some of those things out of the park and some of the new scenes felt like they could be part of that world so they didn’t feel out of place. That was a tough job on their part.”

The dismal and smoky atmosphere of the world aided the game’s mystery story by giving it a visceral tension where action could happen without notice and create real suspense. Yorkin credits the game’s mood and atmosphere to Leary’s story and designs.

“His whole thing which I remember because it was very insightful, he wanted to have a constant tension on whether the detective is a replicant or human and you could take a certain path and find he’s a replicant and go another way and find he’s a human,” Yorkin says. “I think that’s smart because in the end, that’s what’s provocative about Blade Runner. [The movie] never explained whether Deckard was a replicant and it was one of those things I felt should never be explained away.”

The moody atmosphere was perforated by sudden action that kept players on guard such as running after fleeing suspects or choosing whether to shoot or flee an oncoming enemy. Leary says the action added another emotional layer to an already deep experience.

“It wasn’t gonna be a full-on action game,” Leary says. “The movie already has these bursts of surprising violence in action and that’s what we tried to do. You’re going to be shocked by this and it’s going to be over real quick and you’re going to be confused, maybe you did it right and maybe you didn’t. That feel that Deckard is constantly feeling in the movie because let’s face it, he’s not entirely good at his job all the time.”

The noir feel of the story is rolled out by McCoy’s thoughts and observations supplied by Benninghofen’s tempered performance of a gruff working man who questions who he is and what he does.

“They showed me the screen size of the world and I whittled down my tendency to want to be too big and bring it down, down,” Benninghofen says. “I was not Harrison Ford but what I did to my voice back, which was half as young as it is now is sort of roughed it up. A lot about what that game is about is interior monologue, the thing we use in acting that’s older than Shakespeare. Like, oh shit, what are we doing now or lines like, ‘Is she telling the truth?’ to automatically set it in his mind and the player’s mind.”

The voice acting technique were even unique for the industry. Kucan says he didn’t want to keep his actors cooped up in a cold booth trying to predict how the engineers and directors in the soundproof booth wanted you to read them. He wanted his cast to be part of the collaborations so they would have a more active role in the creative process and deliver more personal and genuine performances.

“I always kept the mic open so any of those discussions with maybe the engineer and I would be picked up and part of the process because for me, that’s part of the process of collaboration and putting things together,” Kucan says. “There’s no collaboration when the actors become a prop for directors.”

Just like Ridley Scott’s movie, it took awhile for the game to find a bigger audience following its release but it became a revered adventure title that accomplished something few studios would even try with a movie license for a game. It crafted an original story using the style and rules of the movie that pleased its most ardent fans and could still appeal to gamers who had yet to discover the film especially now that it’s being re-released to a whole new crowd of players.

“It’s a shared story you can talk about with your friends but your experiences are unique and you’re planning for that experience of what does this one guy sitting behind his screen, what is he reacting to,” Kucan says. “That was always in the forefront of my mind, the audience of one versus the audience of hundreds and I think that’s especially true in a game like Blade Runner where the decisions you make and the impressions the game leaves upon you are pretty unique.”

The story, film and game’s vision of a future where technology increasingly encroaches on what it means to be human is also just as relevant and even more appropriate as our future veers towards an increasing reliance on human function replacement, digital companionship and smarter artificial intelligence.

Maybe we’re already there and just like Deckard and McCoy, we just don’t know it yet.

“There are guys who lost their legs in a wreck and before they go to bed, they have to plug in their legs so their legs will be powered in the morning or their legs run off a USB port,” Kucan says. “I’ve seen that video of a little girl throwing a ball and catching it with her artificial hand and as we start moving in that direction more and more rapidly, we’re going to look more to Philip K. Dick as a reminder to what those possible futures really hold.”

Please note, the recent re-release of the game on GOG.com last December, is not due to the work of NightDive Studios, but rather the volunteer work of a small team of developers from the ScummVM project to reverse engineer and re-implement the engine of the game. In addition GOG themselves handled the legal work of acquiring the rights for redistribution.

I’m part of the ScummVM team who worked on the game’s engine and enhancements, such as subtitles support (and complete transcript), numerous original bugs fixed, quality of life improvements for the interface and puzzles, and restoring removed or untriggered content.

To clarify the possible confusion, NightDive Studios are working on a remaster of the original game which is yet to be released, and they are aiming for a release within this year, on Steam, Switch and (I think) other consoles.

Hi there!

Apologies for the mixup there. It should be fixed in the piece now, but please let us know if there are any other errors and we’ll be happy to fix it!

Hi Danny,

Current re-release of Blade Runner on GOG.com has nothing to do with Nightdive Studio, it is a joint effort of ScummVM Team (https://scummvm.org) for the coding part and GOG.com for obtaining the redistribution rights. You may see the words “Powered by ScummVM” on the game page: https://www.gog.com/game/blade_runner

On Steam the game is not yet released.

Attributing Nightdive Studion with the hard work we did is not very nice towards our project and people who spent 8 years on reverse-engineering the game. Nightdive studio so far just _announced_ their work on a Remaster, not about enabling the original to be played on the modern platforms.

Could you please fix the article so it is straight with the facts? You may read a lot online about this, a first-page hit is: https://www.theverge.com/2019/12/17/21026009/blade-runner-1997-adventure-game-online-release-gog And here is our announcement about the game support: https://www.scummvm.org/news/20190616/ And here is the announcement about availability on GOG.com store: https://www.scummvm.org/news/20191217/

Thanks,

Eugene Sandulenko

ScummVM Team Lead

Hi there!

Apologies for the mixup there. It should be fixed in the piece now, but please let us know if there are any other errors and we’ll be happy to fix it!