Review: Sea of Solitude

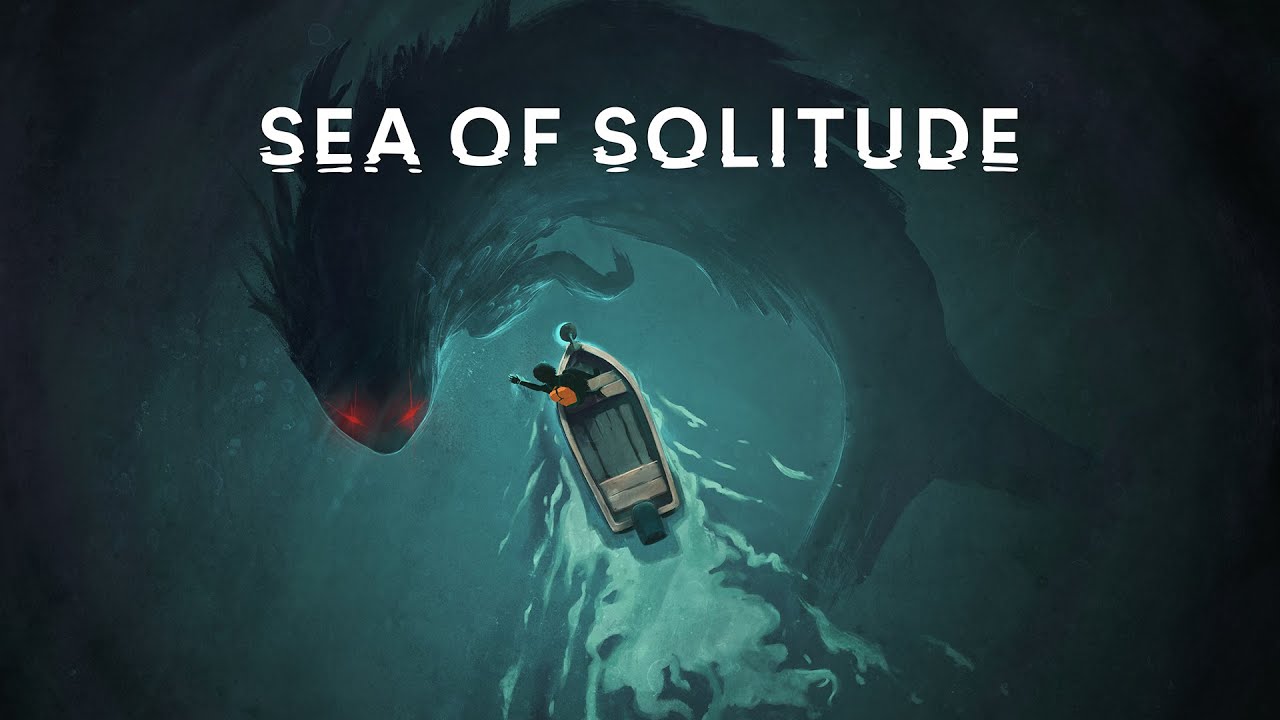

The ocean has always been something that mystifies me. It’s simultaneously the most beautiful and terrifying thing I’ve ever encountered. Berlin-based indie studio Jo-Mei’s new game, Sea of Solitude has managed to evoke this sense more than any other game I’ve played.

In a world where the standard of beauty for games is generally “how photorealistic is it,” Sea of Solitude’s pastel palette and soft, dreamy edges are a breath of fresh air. Moving through the world is a pleasure because even when the gameplay is less than stellar (the platforming and puzzle mechanics are pretty bare bones and leave much to be desired), it’s still a lovely jaunt. There’s a sense of warmth and whimsy in these sections that handily distracts from the fact that the ocean has consumed the city around you.

But that’s the thing: the ocean has swallowed this city, and if given the chance, it, and its frightening denizens, will happily swallow you too. Sea of Solitude’s darker side shines so brightly because it’s able to effectively evoke the sublime horror that is the uncaring vastness of the ocean, and the mysterious monsters that lurk below its depths.

I’m normally not a fan of showing the monster in horror media, because our imaginations tend to be so much scarier, but the fishlike monster that stalks Kay throughout the different watery areas is effective because you can see and hear her. Knowing that she’s always there, ready to snap you up in a pretty brutal, if repetitive, animation keeps things tense as you navigate the water, without the oppressive frustration that plagues games like Outlast.

Other segments inspire fear by flipping the aesthetics on their heads, swapping peaceful color for murky darkness that obscures the paths and platforms you need to traverse, or hides lurking enemies you have to evade in the shadows. These sections can be frustrating mechanically, as it’s easy to lose your way, or fall off a platform and have to start over, but they effectively create a sense of tension that captures the panic and paranoia Kay is experiencing without having to rely on jump scares, over the top gore, or more traditional tropes of “madness” that horror usually deals in. This is extremely key in a game that’s attempting to do trauma and mental illness justice.

What’s conveyed less well, unfortunately, is the narrative we were promised at E3 2018. Originally, Sea of Solitude was pitched as a story about Kay, a young woman whose loneliness and other dark feelings have turned outward and given her a monstrous form. The player is meant to discover how this happened, and try to find a way to reverse it. But that’s not really how the game plays out.

Instead, Kay’s focus becomes understanding the problems and pain the people she cares about most are dealing with, and trying to understand how said problems relate to her and how she moves through the world. The game succeeds in the former, but doesn’t provide enough space to achieve the latter.

Sea of Solitude’s character vignettes are poignant and show relationships and issues I haven’t seen explored in this way in many games. Watching Kay learn hard lessons about her accidental selfishness, and that love isn’t always enough, hit home because I’ve never really seen a character be confronted with the kinds of lessons it feels like I’ve been learning the hard way my whole life. As individual stories, they work well. But combined, they lose some of that strength because they’re not given the space to connect and create a more cohesive vision of what’s been going on in Kay’s head and heart.

By the time endgame begins, it feels like Sea of Solitude is just trying to roll credits. Kay isn’t really given the chance to process how these instances with her loved ones have impacted her life and feelings, so the game ultimately ends up leaving her in the background of her own story. Her own transformation and desire to regain her humanity feel like an afterthought, rushed at the end to wrap up a story that really needed more time to come full circle.

Sea of Solitude has heart, and feeling, and much like the ocean, a wonderful tension between beauty and horror. Its story of family and healing is a refreshing one, especially in a game that could have easily fallen into the trap of “our mental illnesses make us monsters”. But when all is said and done, I can’t help but wish that the game we had been promised had also come to be.

As someone who desperately wanted to see a woman’s journey to confront and accept the darker, messier parts of herself, this felt somewhat like a missed opportunity. Women in mainstream games are never really given the opportunity to be messy and dark, to be monsters in their own perception, instead of being cast in that role by the men in their lives. Women are never allowed to be more than sacred but displaced mothers, boring nags, or literal monsters. But the sum of their parts, both the great and the terrible, can be so much more. And that story is absolutely worth telling.

951896 635603some genuinely choice content on this internet site , saved to my bookmarks . 655037