Dissecting the Anatomy of the Fight in Treachery in Beatdown City

When’s the last time you’ve been in a fight? A real fight, where you and someone else are really and truly putting your hands on each other, doing whatever you could think of to beat someone down, make them either surrender or just hurt too much to fight back anymore. And while you were fighting, how did it feel – how did you feel?

What was your breathing like?

Treachery in Beatdown City feels like breathing. Not a standard inhale and exhale, a relaxed, unconscious rhythm that might be synching up to the same passive beating of your heart. The breathing that TiBC epitomizes is the kind of breathing you have while in a fight – all the kinds of breathing you’ll have while in a fight, the whole spectrum of breaths, and they are many. The slow, deep and loud breaths you have as you brace yourself before launching at your opponent, meticulous and full of violent intent. Or the short, machine gun spray breaths as you scramble backwards, creating distance and trying to get back as much oxygen as possible after feeling someone else’s knuckles dig into all the soft parts of your body. The sharp, harsh breaths you take that have a knife’s edge to them when you’re the one doing the attacking, a furiously exhaled “HRRHHH!” when you’re slamming a knee into someone’s gut or using all of your weight to tackle them to the ground. They’re all there in Treachery in Beatdown City, and just like in a real life fight, all those kinds of breaths connect to each other, there is no one singular rhythm that your body and mind will strictly follow from start to finish.

It’s like a wheel with spokes. The wheel is a whole, complete thing, but is only made as strong as it is by the spokes within it. The spokes are all their individual pieces, yet they all connect to each other, and they connect to each other for the purpose of strengthening the wheel as a whole. When the wheel runs smoothly, you’re not even thinking about all those parts that assemble together to make the wheel, it is simply a ‘wheel’. So it goes for your breathing in a fight. And so it goes for Treachery in Beatdown City, which has dissected the beat ‘em up and exposed the inner guts of the genre, how it all works, then refined and tuned up each individual part of this genre, connected and balanced each piece with every other piece, and then assembled all of that together to make for a smooth, strong whole of a game that would not be the same if you took any piece of it out.

So it goes for the wheel and its spokes. So it goes for your body in the middle of a fight, and how all that muscle in your arms and legs won’t do you any good if your lungs aren’t getting any oxygen in them.

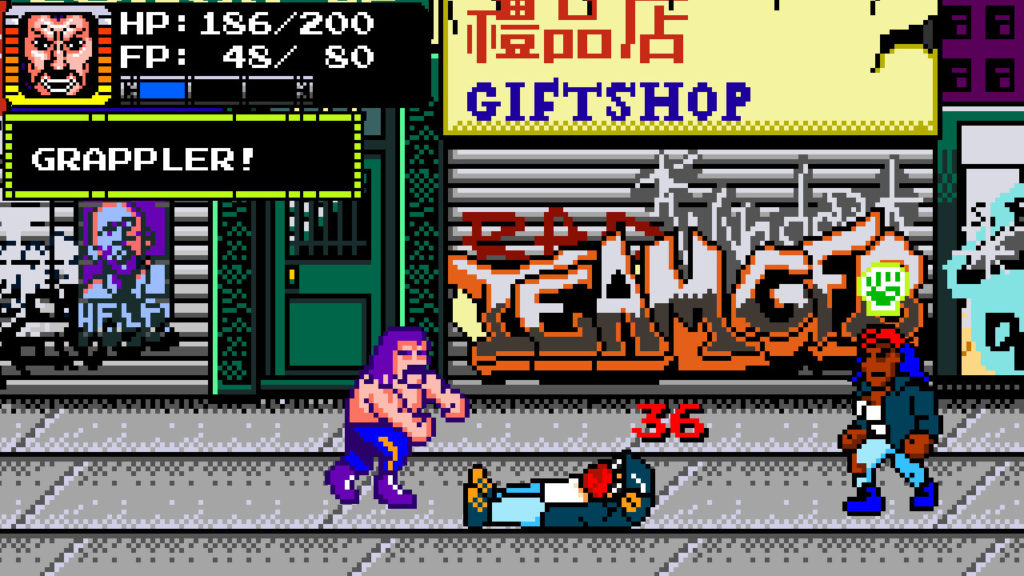

The body, so to speak, of Treachery in Beatdown City is simple enough to describe. It’s a beat ‘em up with a semi-turn based combat system, taking heavy stylistic inspiration from the iconic games in this genre from the 80s and 90s, like Streets of Rage and Final Fight. When you wanna do all those flashy moves you could normally find within the genre, instead of pressing a dedicated special button or mashing the attack button and maybe some directional inputs, you make the whole game come to a pause and open up a combo menu, where your full moveset becomes available. There’s a dedicated quick strike button too, which lets you do basic attacks without draining your Fight Points, but does use up your Action Bar when a hit connects. So you can do basic damage while still storing and building up precious FP, but you have to keep in mind how much of your Action Bar you’ve got available – or how much you’re willing to spend – so you can cut loose with your combos at all, or to make sure you have the bar needed to do a counter when somebody’s about to wail on you.

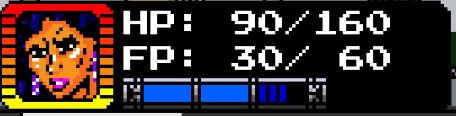

Bringing all that up though makes the obvious questions come around: What are Fight Points? What’s the Action Bar? How do they work, why do they matter? These two stats are where TiBC’s polished design begins to reveal itself, to show that rhythm and flow of the game, the way it breathes from moment to moment. The Action Bar and Fight Points are the lungs of TiBC’s body, and like our own, every other part of it connects to, and is affected by, that flow of oxygen.

Before I get into what the Action Bar is and what Fight Points actually are, I first want to make a small note on how they work: they recover. They refresh over time. The same goes for everything else but your hit points. Your AB will refill naturally when you aren’t doing moves. Your FP will build back up on its own. You will never find yourself in a situation where it is impossible to do anything because you lack either AB or FP, so long as you can take enough time to let them recover on their own. Again, it’s like breathing. You might be short of breath for a while at one moment because you just did an awful lot of physical work (or perhaps got into a real fight), but give yourself enough time and it’ll all come back.

An extra tweak from there: you recover FP naturally, but you can also get significantly more FP from combo and grapple bonuses. Like an adrenaline spike in the middle of doing something that should leave you worn out, suddenly you have more energy than you started with, because now you’ve got your blood flowing properly.

I want you to keep all this in mind, because everything else in the game is designed and balanced around it. These pieces connect to every other part and make the whole system of Treachery in Beatdown City the smooth running machine that it is.

Fight Points are simple enough – they’re like a modified form of MP from RPGs. You need them to be able to do anything in your combo menu. Just as you can’t summon Ifrit without enough MP, you’re not gonna be pulling out a brainbuster if you don’t have enough FP for it. There are a couple key differences between MP and FP. First is the aforementioned recovery system. Second is that in Beatdown City, you don’t start a fight with whatever FP you had at the end of the last one. There’s no rollover of FP, but you can’t zero out on it either and enter a fight with no FP at all. You have a fixed amount of FP when you start, and you can get more by waiting, by using items, or through attack bonuses. But once the fight’s done, that’s it, the FP resets back to that fixed amount for the next match. You can’t farm FP from one fight to use in the next so you can immediately use your best chains and special attacks, you’re starting each round fresh and have to build up that momentum to unleash your most powerful attacks again.

The Action Bar also seems simple on its face, but hidden inside of its design, inside of all of its connections with every other aspect of the game, comes powerful complexity and an incredible evolution of more traditional turn based RPG combat systems.

I called TiBC a “semi-turn based” game earlier, but that is a simplification of the depth of what is at hand here. The combat isn’t action focused the way something like Star Ocean: The Second Story would be, nor even like Secret of Mana which has you charging up bar after bar for your strongest attacks. It’s not like the fast paced combo system of a Valkyrie Profile, and it’s not the classic methodical nature of a Dragon Quest or a Shin Megami Tensei.

The way TiBC’s turns are structured feel most like an – incredible – evolution of the Active Time Battle system from Square-Enix, first introduced in Final Fantasy 4, but what Beatdown City makes my memory pull from is Final Fantasy 6 most of all, thanks to one particular character in it. What makes TiBC’s concept of turns so different from so many other games is the way a turn is itself structured.

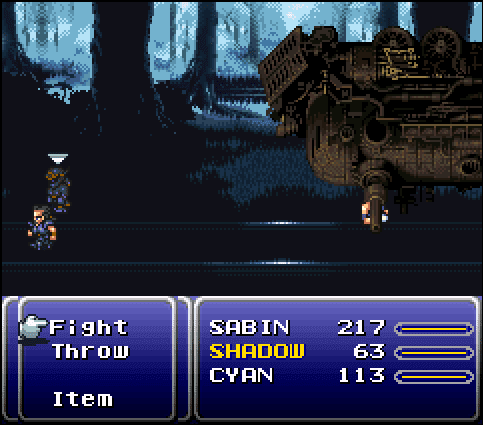

The oldest turn based RPG combat styles are just that, turn based. You and the opponent take turns until one of you are dead and that’s that. Squaresoft evolved on this in Final Fantasy 4 with the Active Time Battle system, where turns were not a one to one affair, but each character had their own naturally filling up bar that, once at maximum, could be used to execute a turn. Made combat more fluid and a hell of a lot faster since you couldn’t agonize over each and every last decision – hesitating for too long would just open you up for taking more damage as the enemies took their turns while you were still figuring out yours. Beatdown City’s combat system takes that revolution of the ATB system and evolves it further. The basic idea is the same, as TiBC has the Action Bar, which also fills up over time and lets you open up your command menu. What’s new is the math, so to speak, of turns. In Squaresoft’s ATB system, one full bar equals one turn, and one turn is only one turn. For Treachery in Beatdown City, a full action bar equals one turn, but one turn equals three turns. Now, how can one turn equal three turns while still being, at its whole, one turn? To explain that, we go not to Final Fantasy 4, but to two games later, Final Fantasy 6. It’s there where Squaresoft created the brawler character Sabin Figaro, who is mechanically most like all of your fighters of choice in Beatdown City, thanks to his physically focused attack and his character unique ‘Blitz’ attacks. And it’s with him I can best explain TiBC’s evolution on Squaresoft’s ideas, with what I call the Sabin³ system.

To illustrate the principles of Sabin³, let’s use one of the most well known encounters in Final Fantasy 6: The Ghost Train fight. For this part of FF6, you only have three characters: Shadow, Cyan, and of course, most importantly, Sabin. Sabin, being a brawler, is the most natural comparison to any beat ‘em up characters, especially since his Blitz attacks famously allow him to suplex almost any enemy in the game. Including the Ghost Train itself.

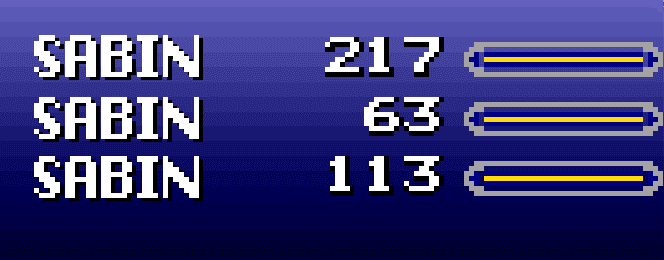

Let’s imagine that for the Ghost Train fight, Shadow and Cyan are not actually your other party members. Instead, Cyan has been replaced by Sabin. And Shadow is also gone, having been replaced by Also Sabin. With this kind of setup, you would then be able to do three different Blitz attacks total across characters once their individual ATB meters are filled. But this dynamic is still not quite Sabin³.

The crucial second step of Sabin³ is to take those second and third Sabins, and then fuse them into the first Sabin. Now instead of having three individual Sabins, you have Sabin³. You might wonder “Well what’s the difference? What’s the point? You still get three attacks, three chances to attack, to use a Blitz move, or to use items, right?”. On its face, this is true. But the difference between three Sabins and Sabin³, and what is the key design piece of Treachery In Beatdown City that everything else is formed around, is still how you define a ‘turn’.

With three Sabins, you have three different, individual turns, one for each character.

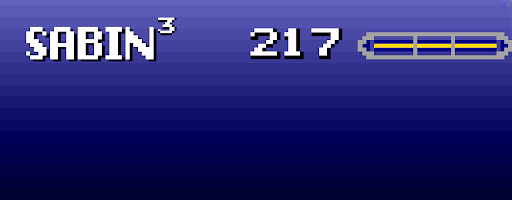

With Sabin³, you have one turn that has three turns inside of it. Every turn is – potentially – three turns. A full ATB bar for Sabin, a full “turn”, would give Sabin three turns inside that turn, before needing to wait to fill the bar up again.

If this definition still seems weird, confusing, or just plain pedantic and/or stupid, let’s use a Sabin³ modification of FF6’s ATB bar, and then Treachery’s action meter to give you a visual representation of how “three turns in one” works.

One turn = three turns. Treachery in Beatdown City might be quickest to describe as a turn-based beat ‘em up, but trying to sum it up in that, or even just as a ‘semi-turn based beat ‘em up’ doesn’t do it justice. While it might take inspiration from the Active Time Battle system, it builds on it to make an incredibly fine tuned combat system that feels like it could be the foundation for not only the next evolution of beat ‘em ups, but of RPG combat systems as well. The reason being that the three turns you have aren’t just a chance to do three separate moves, three different attacks to get in one big chunk of damage in total.

With three turns inside one turn, you can do more than individual attacks. You can do combos. And what combos can do in TiBC is much more than “extra damage”. More spokes keep getting added to the wheel.

While Beatdown City takes inspiration from turn based games, it reorganizes its structure to value and reward momentum in a player. Instead of a rapidly tedious “you go, now I go, now you go” back and forth, combat actually picks up speed and intensity as you and your enemies start trading blows. It’s not simply that HP goes down as you trade blows and that, obviously, accelerates towards the end of combat. It’s the whole of what your attacks do, what your combos do. Raw damage numbers are never the only thing at play in a fight.

The first part about combos comes back to what I said earlier about FP: building up a chain of attacks costs you FP, but if your combo is successful, you also recover bonus FP once it finishes. You gotta spend FP to make FP, and you’ll get FP faster and in greater quantities from putting together combos than you ever will from walking around the screen and waiting for those numbers to tick up. All the systems encourage you to get up in someone’s face and start swinging and to take the risk that they’ll swing right back. If you wanna use those big, badass moves, you gotta earn them, you gotta build up the momentum and get your character’s blood pumping to go for those high cost attacks.

The second part about combos is the way they implement that part of RPGs that’s so difficult to balance, often going completely ignored by players as something they could use in a battle, because “Why bother?”

Status effects.

In all too many RPGs, every buff or debuff spell you come across feels like it’s there for the sake of being there, to continue an ongoing tradition of other games having status effects. More often than not, they’re an annoyance to your own characters and rarely feel like anything that’s going to be helpful against enemies. It’s a slight tweak here and there, and you slightly tweak to adjust to it, but in too few battle systems does it ever feel like anything worth paying attention to and using regularly yourself. After all, why bother when you can just keep dealing out more raw damage? A turn spent on a spell that makes a slight change to an enemy’s defense stat feels like a turn you could’ve spent hitting them the strongest attack you’ve got. Or like running across equipment that gives a 5% bonus to lightning resistance – who has ever felt truly compelled to use any of that, been excited and engaged with any of that?

TiBC tackles this from two angles. First is the fact that status effects actually matter, for both you and your opponent. Getting your accuracy up matters, slowing down your opponent matters, making them bleed matters, and whether one of you has stun status on really does matter, and it really can make you pissed off or incredibly smug depending on which of you is afflicted with it. Boosting yourself has a real impact on not only your individual attacks but also on whether or not you’re gonna win that fight. In the late game, getting buffs and debuffs set up can easily make the difference between enemies stepping all over you and you cutting them down like wheat. An extra tactical layer is placed on top with the fact that any one fighter can only have four status effects, positive or negative, active at any time. This pushes you to start trying to buff yourself and debuff your opponent as quickly as possible, before they can stack something on you to leave you struggling, and before they can pump themselves up to do extra devastating damage to you.

The second way TiBC makes status effects matter is how you inflict them. You have individual attacks that have chances to inflict things like bleeding, but your best options to give yourself an extra boost and give an opponent something else to chew on is through combos – and where we get the difference between three Sabins and Sabin³, the difference between three turns and “every turn is three turns”.

If you had three separate turns, three separate Sabins, what you might end up doing is picking two physical attacks and one status effect focused move, to give yourself an extra boost or to hamper that Ghost Train’s strength a little more. But with three turns in one, with Sabin³, you could select two or three attacks that, when chained together, cast those buffs and debuffs. Instead of separating status effect moves from attacks, TiBC fuses them together, then balances the game’s difficulty to push you further into actually giving a damn about getting those status effects in. Several individual strikes and grapples have the chance of inflicting status effects on their own, and many of the combos you can do will give yourself a boost for performing them. You don’t have to choose either pummeling the biker in front of you or giving yourself an accuracy boost for your next plan of attack – TiBC wants you to do both, incentivizes you to open up that combo menu, cash that FP, risk those Action Bars, because a success means you get that raw damage, a buff/debuff you wanted to use, and extra FP recovered at the end from the combo bonus. You get that opening combo in, you do some damage to their HP, you give yourself a boost, you get more FP, and then when your action bar refills you can now go in even harder. Use bigger moves, stronger combos, more status effects. You get the blood pumping, you get that adrenaline flowing, and the fight accelerates. In most turn based systems, you’d likely be using the strongest moves you had out of the gate and as much as possible; why use Lightning 1 when you have Lightning 3? Why use “Jab” when you can use “100 Fists Of The Heavens”? And why bother lowering their defense if it just eats up a turn you could spend thrashing the enemy more?

But it all chains together here. Each part connecting to, feeding into every other part. Raw HP damage even plays into the other systems as well; some attacks have a low chance of success when your opponent has high HP, further discouraging “use the strongest thing you’ve got from the start” style combat. Setting up a real rhythm and flow from attack to attack, each one building up momentum into the next, all systems eventually converging together into one spot where you have the FP needed to use those stronger attacks at all, the status effects necessary to boost the odds of them connecting, and having whittled down enough of your opponent’s HP that they’re far less likely to block, dodge, or counter whatever you’re about to throw at them. Not a single piece feels isolated from the rest, all those spokes are still tightly fitted next to each other within that wheel. The lungs keep pumping oxygen into the rest of the body, the body gets that blood flowing, that blood helps the lungs keep pumping more oxygen. Everything your body does connects back to itself, every part of a bike needs every other part of a bike, and every system in TiBC flows into every other system.

This includes when those systems are interrupted.

So let’s talk blocks and counters. Let’s talk how Beatdown City approaches the defensive side of a fight, and how it develops one of Beatdown City’s core systemic and thematic ideas: every fight is a gamble. You cannot expect to hit someone and not get hit back. Anything you can do can be done to you.

The first part of “Anything you can do can be done to you” is still on the offensive part of TiBC. Strikes, combos, grapples and status effects, everything you’re throwing at someone can be and will be thrown right back at you. They have a knife that they’re stabbing you with? You could always knock it out of their hands, take it from them, and stab back… which they can then do to you. You could have a whole match of knife hot potato, neither you nor them having any clear advantage. A knife is still a knife no matter whose hands it’s in, and it can be knocked out of your grip just as easily as you can knock it out of theirs.

This balancing act continues into TiBC’s defensive tools, which, if you know your beat ‘em ups, stand out for being accessible to the player at all. In much of the genre, blocking is an act reserved for the opposition. You can attack and you can dodge, but rarely can you do that most basic of fighting techniques and put your hands in front of your face. Some of my favorite games are even specifically designed and balanced around the inability for the player to block. God Hand, for example, dedicates an entire analog stick to dodging but has not a single blocking technique, even though enemies can and will block your attacks, to such a degree that there are multiple dedicated block breaking attacks you’ll have to use if you wanna win. Some of the beat ‘em ups you can feel the heaviest influence on Treachery in Beatdown City – Double Dragon, Streets of Rage, Final Fight – also lack the ability to block.

But to keep up the way TiBC thinks about balance and stick to its approach of “anything you can do can be done to you”, the reverse must hold true as well. Blocks must be as much a part of the player’s arsenal as the enemy’s.

Compared to strikes and grapples, your defensive moves are not great in number. You can brace yourself, you can block, you can counter, and if you’re facing the other way from an oncoming blow, you can turn around. For the majority of the game? That’s it! You never have to be overwhelmed by choices when you’re getting attacked. Bracing costs 0 FP, blocking costs a small amount of FP, a counter costs a single action bar, and turning around costs a little more FP than blocking.

Let’s work backwards there to show how defense is assembled in Beatdown City: you cannot turn around and block. And getting attacked from behind does extra damage. If someone’s coming up behind you to suckerpunch the back of your head, your only choices are to hunker down and brace yourself for it, or to turn around and take it head on. If you want to actually block and counter, you not only need the required FP or an unused action bar, you need to be facing forward when someone takes a swing at you. In essence, if you want to avoid the worst damage, you can’t just turn your back and run away, as that’s a recipe for getting hurt even worse. You need to keep yourself in the heat of the fight. If someone’s trying to hit you, you wanna know how they’re attacking you if you’re gonna try and block it – are you really sharp enough to think you know the difference between how a right hook and a left hook sounds when it’s coming at you from behind? Which goes double for countering. It feels riskier, but when you’re in a fight you can’t opt out of, you want to keep your eyes on the threat in front of you. Even Ali bobbing and weaving his way through a flurry of blows from the ropes did it while looking right at Michael Dokes. That extra FP cost on turning around is an extra twist on the screws, the game continuing to quietly pressure you through its mechanics to not run up, attack, then pivot 180 and run away. More often than not, hitting some yuppie punk in TiBC and turning your back on them will just result in you eating shit, or spending precious FP and still eating some shit anyway.

So, say a cop in TiBC gets up close and starts their attack, and you’re facing them head on when they do. You can brace, block, or counter. Brace costs you nothing, block still costs you some FP, and a counter will still cost an action bar. Block has the chance of negating damage, and counter has the chance of completely stopping an attack in its tracks, not only avoiding taking damage yourself, but taking a nice chunk of HP out of your attacker’s life bar, and can even knock them to the ground, where they’ll have to take a moment to get back up. In that time, they won’t be able to attack you, won’t even be able to chase you, making the moments after a successful counter one of the only times you’re given the safety to turn tail and put some distance between you and them.

You might figure “Well, so long as I have the FP or a free action bar, I’ll just use block or counter every time, right? Why wouldn’t I?” And there’s two major reasons you wouldn’t.

- Blocks can fail, and counters can miss. Like with everything else in the game, when you make those choices, you’re gambling that FP and those action bars. Some moves have better odds than others, but there is no guaranteed success. And if you spend that FP or that AB with nothing to show for it, then you’re at a disadvantage when you want to take your turn to attack.

- You literally can’t.

It is impossible to effectively adopt a turtle defense in Beatdown City. Even if you had infinite FP and infinite action bars, you cannot just constantly mash block and counter – the game won’t let you. I mentioned earlier that your FP and action bars naturally recover over time. So do your moves. If you select a block or a counter, you’ll have a little bit of time before you can block or counter again. Only ‘Brace’ is available as a choice no matter what, since it doesn’t help you any, you’re getting hit all the same. You cannot just hold back and wait for the perfect opening like you might in a fighting game, or wait for a full action bar and mash counter for every fist and foot coming your way.

The same goes for your attacks, by the way. Even in a hypothetical god mode with infinite FP and action bars, that recovery time between moves would still keep you from just picking the strongest attack over and over and over again. Each system interlocks with each other, but are also designed on their own to keep you from even thinking you can just do one thing endlessly and win. There’s no infinite loop you can set up. You can’t even use basic strikes endlessly, your action bar will zero out and you’ll need to take a moment before throwing a fist out. Where Double Dragon and Streets of Rage would punish button mashing by having enemies that would knock you flat on your ass if you tried to spam them, Treachery In Beatdown City literally takes the tool away at all. There’s a joke screen in the game, hearkening back to the days of arcades always featuring a message from William S. Sessions, but Treachery In Beatdown City isn’t kidding when it says:

In most beat ‘em ups, you shouldn’t button mash. It’ll just lead to you getting your ass whooped. Treachery In Beatdown City takes that unspoken lesson to a natural evolution and makes it so you are completely unable to button mash. Can’t spam any attack, any block, any counter. You engage with the whole of their systems in a fight or you get your block rocked. Imagine walking into a fight and, from start to finish, doing nothing but spin kicks. Like a 5th grader at their very first karate class, nothing but yelling and spin kicks. People are going to figure out you’re just gonna keep spin kicking, keep hoping they walk into it, and you’re gonna end up getting a whole bunch of knuckles in the gut for it. You have no choice but to engage with all of TiBC’s systems. There’s no available path to just ignore some pieces and try to find some min/max trickery to cheese the game. The game not having any stats to boost other than HP and FP when you level up reinforces that – there’s no stat, no skill tree, and no particular strategy you can dump all your focus into and disregard the rest and still expect to win. You have to fight, and you have to keep adapting to how the fight flows, or you’re gonna get trashed.

With all these systems and mechanics in play, one could understandably think that TiBC might fall to the problem of choice paralysis that can happen in turn based games, particularly tactics and strategy ones. Like how people agonized over their moves in Into The Breach, trying to think many steps ahead. It’s easy to end up staring at your screen for half an hour or more, like how people can agonize over their turn in chess, as you try to think of every strategy you can take, every move that can be used against you, looking for a way to get ahead without losing anything, trying to find the “perfect move”.

But Treachery In Beatdown City never has that problem. If anything, the longer the game went on, the more systems and moves were introduced, the faster I was picking my attack plans whenever I walked up to some meathead bruiser in my way. I never felt that slowdown, that urge to find the perfect move.

Because in Beatdown City, there isn’t one.

To get at the heart of what Treachery in Beatdown City does so well with its combat, I find it important to contrast it not with other action games and beat ‘em ups that are bad what they do, but ones that are also deeply fine tuned and balanced around their ideas, their systems, what they want a player to prioritize in a fight. God Hand and Bayonetta are two clear examples for me, being considered some of the best in their genres, their combat systems honed to a fine point, just like TiBC does – but while the skill across all three feels equal, the way those systems are executed, and for what purpose, is vastly different when you put God Hand and Bayonetta next to Beatdown City.

As beat ‘em ups go and action games go, God Hand and Bayonetta are far more fast paced, twitchier affairs than Beatdown City is, or the games it’s taking much of its own influence from. Where TiBC and God Hand and Bayonetta find similarities are in emphasizing the need to get up close and stay in someone’s face with your attacks. Even with adding guns into the mix for Bayonetta, if you want to do real damage on enemies and finish them off, you need to close the gap.

There are two key factors where Bayonetta and God Hand differ. The first I’ve already mentioned: blocking, or the lack thereof. God Hand and Bayonetta give you no block, no way to reduce the damage coming at you. It’s all about dodging. You either get hit all the way or not at all.

The second factor builds off that first one: How these games define the idea of ‘risk’.

God Hand and Bayonetta will challenge you, punish you, make it hard to win. But if you do sink the time and effort into their systems and mastering them, you won’t just win: you’ll have flawless victories. Bayonetta has ranking systems and rewards for multiple chunks of each level, with Platinum as the highest, to give players more reason to go all in on figuring out how to win a fight as fast as possible while taking no damage at all. Flawless dodging. Not a dent on your life bar, not a single bruise on your person. It’s incredibly difficult to pull these things off, but it is still possible. The better you get, the more you minimize the risk in a fight, till eventually you have enough skill that the risk factor becomes zero. The best players of these games, and those who have found various exploits in their system, can beat both of them start to finish without taking a single hit. To master combat in Bayonetta and God Hand is to push yourself towards the feeling of being an unstoppable god of fighting; fitting, considering protagonists in both are superhumanly powered agents of destruction. When you have an arm that can punch people so hard they’re launched into the horizon, or when you’re a witch who can summon massive magical creatures that will feed on your enemies, why not structure those combat systems to make it possible that the player eventually feels functionally invincible, unstoppable?

But you’re not some divine warrior in Beatdown City. You are a trio of people who are all pretty good at fighting and taking a hit, and that’s all you are. There’s no calling on the powers above or the demons below to give you strength when you punch some jerk in the street hassling you while you’re trying to get to city hall. There’s just you, them, and all the bone and muscle and blood that make up both of you. And more often than not in a real life scrap, both the winner and the loser are going to end up feeling the hurt.

You can, should, and will get better at fighting as you play Treachery in Beatdown City. But no matter what you do, no matter how good you get at the game, there will always be risk. There is no skill, no strategy, and no exploit I know of that will allow you to win every time without ever taking a hit. Every time you get into a fight, every time you open up that combo menu, every time you select your attacks, every time you choose ‘counter’ on the defense menu, you are taking a risk of getting hit. You are rolling the dice every time you put your fists up. Your best combo might be countered, your blocks could fail, your counter could completely whiff. You cannot start dozens of fights and expect to come out of all of them smelling like roses, no matter how good you are. You cannot hit someone and expect them to not hit back. Even Jackie Chan gets the shit kicked out of him in his movies by nameless punks before kicking them through a wall. And you’re not Jackie Chan, are you?

Like I said before: There is no ‘perfect move’ in Beatdown City. There is no flawless strategy. Even when squaring off with some condescending polo wearing gentrifying jackass, there is always the chance that you might have a right hook and they manage to get a punch straight into your nose. You could still win the fight. You might win it handily, that one punch to the face the only strike they get in. But there is nothing you can do to avoid ever getting hit. Keep getting into fights and inevitably your knuckles will get bloody, your knees will get scraped, pock marks of bruises will trail up and down your body, and you’ll be sore all over. You select your best attack in Beatdown City, the number crunchers inside roll the dice, and they decide how that goes for you. Even if the probability of success was 99 percent, there’s always that last chance of failure. You’ve heard about boxers and fighters with perfect win records, but when have you ever heard of a fighter who has never gotten hit?

From a mechanical standpoint, taking away any possibility of a flawless, no-hit run of the game is another piece of the systems that keeps the machine as a whole so smoothly balanced. Since there’s no perfect move, you don’t spend needless time staring at your screen trying to find one; you go with what you think’ll work best and roll the dice, which keeps combat from ever feeling slow and tedious. It’s vitally important to the difficulty balance of TiBC as well. Beatdown City wants to be challenging, not frustrating/impossible, or the kind of power fantasy that ends up boring you by making you feel less like you’re powerful and more like everyone else is comically weak. To use the comparison of Jackie Chan movies again, how much would you have liked Legend of Drunken Master if Jackie just blew his way through everyone that looked the wrong way at him?

The taste of victory in a brawl is that much more satisfying when everybody you took down didn’t look like they were taking a fall. Treachery in Beatdown City won’t get the reputation for difficulty that games like God Hand or the Souls series have, but it’d be remiss to not notice it. It’s so incredibly balanced, its systems so perfectly in tune with each other, that the difficulty always feels ‘just right’. It doesn’t stick out the way a much harder or much easier game would, and if you ask me, it’s accomplishing something far more uncommon because of that.

Putting together a system with all these sub-systems within it, all these moving parts that depend on every other moving part, to make a difficulty curve that feels like it has achieved some platonic ideal, to the point you might not even think about it, that is an incredible rarity in game design. It doesn’t need to throw huge waves of enemies or dole out damage sponges that feel more like a chore than a challenge to keep you on your toes. All of the individual cogs of the machine, the spokes in the wheel, are already working together to make the whole product run so well you don’t notice how impressive it is. It’s not a challenge to make a game too hard or too easy, finding a groove that players can follow along without once feeling disconnected or bored, that’s hard.

And that’s all impressive on its own to me, as someone who loves beat ‘em ups, loves studying them, loves taking them apart and seeing them tick, the same way Nuchallenger obviously did with making Treachery in Beatdown City. I’ve believed for a good long while now that beat ‘em ups are ‘dumb’ games with complex systems quietly spinning along underneath, that so often the best in the genre are the best because they were put together in a way that we never think too much deeper than “punching feel good”. Often we might only begin to notice the systems at play in beat ‘em ups when we find one that doesn’t work well, when we can feel the machine inside missing pieces, and think to ourselves “Punching doesn’t feel good. Why?” TiBC is a masterclass in those systems and does it while showing them to the player, so they too can start to piece together the oft invisible mechanics of the genre. But there is an additional manner that Beatdown City puts all its systems together that leaves an impression on me. Something more in your bones and in your blood than in words and code.

It feels like a fight. It feels like fights, plural. Moment to moment, fight to fight, it reminds me of getting into fights myself years ago. How it actually feels, not how you imagine it would feel to be an unstoppable badass. It has the proper mood of a real, honest brawl, when you and some other jackass (as you could very well also be the jackass in a fight, as I have been before) are sincerely trying to beat the shit out of each other, and it could shake out either way who the winner is. Even in times where I won the fight, I was still sore and ached afterwards, I still had to take deep breaths to get my wind back. Treachery in Beatdown City wants you to throw down, but within its 80s/90s beat ‘em ups and comedy magazines styles and sensibilities, it still wants you to feel what it’s really like to throw down. You’re not the baddest motherfucker on the block, and even if you are, eventually some other, equally bad motherfucker is going to come around and wanna see just how tough you are.

There is no perfect move. There is no flawless victory. A fight is always a risk. A thrown fist is always a gamble. And no one can get into a fight every day of the week and not come out aching all over at the end of it.

I’ve compared Beatdown City’s inner workings to breathing, thanks to the way every part of the game refreshes and recovers over time, and with how much each piece is necessary for every other piece, like oxygen for your body, and that the rhythm of your breath will change before, during, and after a fight, but there’s one particular detail of the game that got me on this comparison in the first place.

When you use up all of your action bars, they naturally begin to recover. And so long as you aren’t attacking or countering every single time before they can reach the third bar, you’ll eventually get your full meter back. The timing of how each bar refills caught my eye early on, though.

The first and second bar recover fairly quickly. With the third bar, however, you’ll start to notice all the little ticks of blue filling in just a little slower, just gradually covering that empty black space. Still, you don’t immediately recover your last action bar once all those blue ticks have taken over the entire space.

There’s a slight delay, a pause.

And then a DING, and your full blue action bar comes back.

It was that delay that got me thinking about breathing in regards to Beatdown City. I remembered the way I breathed while in a fight, particularly the kinda breathing I had where I was trying to get my breath back, either because I overextended myself or because I simply ate shit on a blow I failed to block. Getting distance between me and them, breathing fast and hard at first just to get back to normal, and then – a long, deliberate inhale…

And DING, exhale. I could start fighting again.

Treachery in Beatdown City isn’t a simple love letter to old beat ‘em ups, it is an expert study of them and an astonishing evolution of them. Of turn based combat systems generally, in RPGs and elsewhere. TiBC doesn’t look to recreate or imitate the way those old games made you feel. It took them seriously, pored over them, found what worked, what didn’t, and out of that dissection created a stunningly intricate combat system that ends up flowing together effortlessly, in turn creating a level of balanced challenge that other games would kill to do as well, creating a game that makes fights feel like the way fights should.

Like your body is a complex machine of so many moving parts that would make you sick and dizzy if you were consciously aware of all of their inner workings, but breathing feels like the most natural thing in the world. That’s Treachery in Beatdown City. And I can’t wait for more of it.

keep on posting