25 Years In The Making: The Strange, Real World of Ace Combat

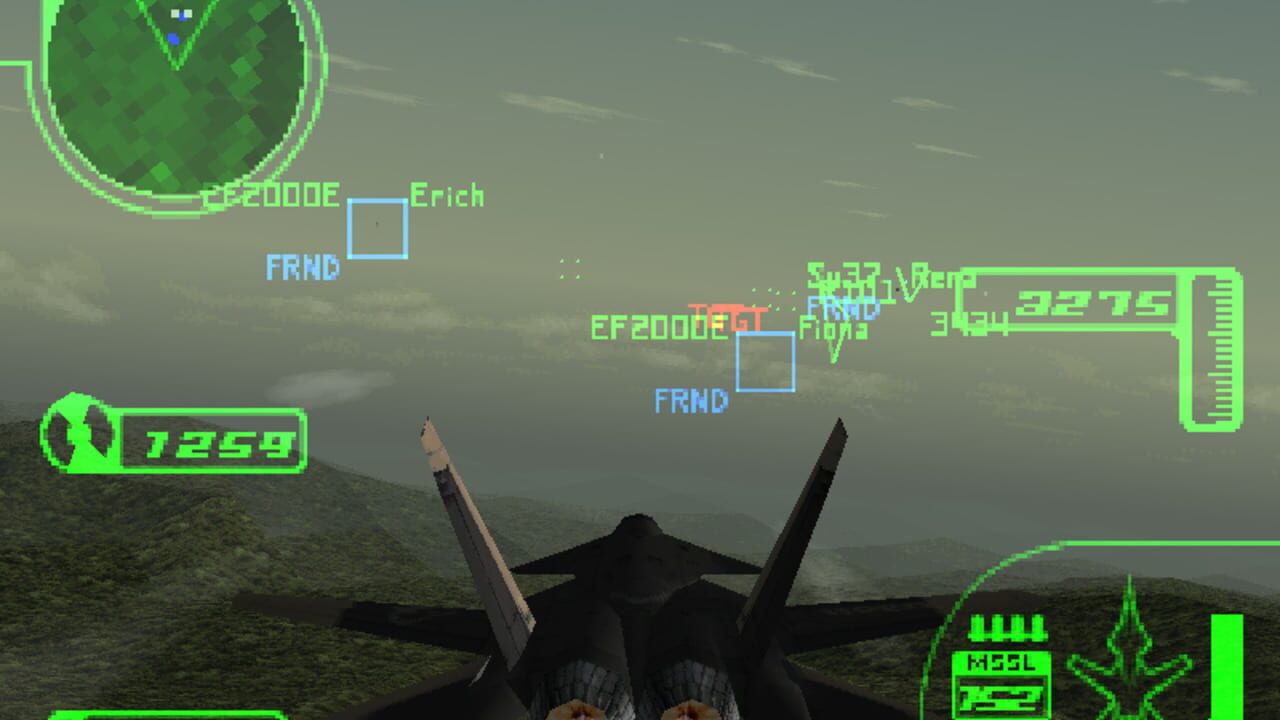

25 years ago today, Ace Combat launched on the PS1. The title would land in North America two months later as Air Combat, the name of the 1993 cabinet the game was based on. And as the console generations have since passed, Ace Combat has gone too in pursuit of flight. Appearing on everything from iOS and the Gameboy to Steam and the PS4, the past quarter century has left us 17 Ace Combat titles richer.

I mark two constants throughout the sea of change. Meet Kazutoki Kono. Serving some role on every core title since Ace Combat 2 (1997), Kono is the face of the Project Aces, the studio behind the games. Now, as Brand Director on last year’s Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown, he’s approached auteur status among some in the dedicated fan community. I reached out to Kono via publisher Bandai Namco’s North American PR at fortyseven in January. Given the ensuing year (and a language barrier), we were constrained to an email interview. I asked him about the development not of the game, but the world. Welcome to Strangereal, strap into your seats and enjoy your flight.

21 years ago, in another world, an asteroid named Ulysses 1994XF04 crashed into the Earth. Strangereal, the very not-fictional universe where almost every Ace Combat game takes place, originated during the development of Ace Combat 04: Shattered Skies (2001). “We didn’t approach its creation like, ‘Let’s create the Strangereal universe,’” Kono writes, “but there were visuals and story elements that were necessary for AC04.” Project Aces needed a narrative justification for the set pieces they wanted to pull off, and neither Earth’s geography or history would satisfy. “Creating the world of Strangereal required us to ‘reset the world setting of players and build a new world that was beyond players’ imagination,’” one where airborne aircraft carriers and giant super weapons weren’t out of the ordinary. “It was necessary to have one unimaginably critical incident take place that would involve the entire planet. So, I think we don’t need ever to retell of the fall of Ulysses in the game.”

But placing all of Ace Combat into one universe had some repercussions. Namely, it’s timeline. AC04 was set in 2004, while it’s predecessor, Ace Combat 3: Electrosphere (1999), was set in a sci-fi 2040. Not only did Project Aces need to justify its current setting, but also set the stage for the inevitability of future flight. This is a thread still being woven today, actually. AC7’s DLC introduces us to fictional prototypes of what’s to come in 20 years in Strangereal’s future and 20 years ago in ours.

Kono tells me this wasn’t any problem for the writing team and Sunao Katabuchi, who wrote for AC04 and Ace Combat 5: The Unsung War (2004). “The flow of the story in AC7 was going to be the natural progression of the world and the history of 04 and 5 that we were already familiar with.” All Aces had to do, then, was allude to the visuals and narrative of AC3. This resulted in some name drops for fans and cool planes. Kono says, “in that sense, I didn’t feel too much of a restriction.” Though AC3 was previously adopted into the UGSF, Bandai Namco’s expanded sci-fi universe, no Galaxians have been alluded to.

When the stars fell from the skies, they built a cannon to destroy them. What really propelled Strangereal’s technology into the near future was the struggle to engineer super weapons that could protect the surface. At first there was global cooperation, but as the asteroid neared, tests failed, and deadlines passed, each nation was left on its own. Disparity was branded upon the nations of the Earth as meteorites bombarded the surface for days.

As an ace pilot, the player navigates the wreckage of planetfall. Whether it’s the sunken capital city of a former superpower in a newly formed crater, or the run-down array of ground-to-air rail guns that were damaged in some other war already, Strangereal is still an apocalyptic setting. Kono says that the team recontextualizes histories from across the globe in its nations as “a foothold for players to imagine what is not depicted in the game. This allows for stories that were not written by us to be born inside the players’ minds.” It’s not just that the names of countries are different, but that “the nations of Strangereal have taken their own course – they enact policies and head in directions that are far different from the real life countries we used as references, and act in ways we couldn’t imagine.” Refugee crises, militarization, civil war, definitely-not-just-the-German-occupation-of-France, armament, countless coups, profiteering, drone warfare, these all belie an overarching threat to the Strangereal. Another story.

25 years ago, Belka, a small nation under siege by the neighboring Osean Federation and several liberated territories, detonated seven nuclear bombs on its own soil to prevent the inevitable invasion. Officially, 12,000 Belkan’s died and the northern territory became too irradiated to inhabit, much less conquer. The Belkans that survived lost not only their nation, but their homeland, serving to radicalize a generation of rogue elements. After planetfall, Belkan agents like the Grey Men or Dr. Schroeder provoked international conflict for decades to come. Behind these conflicts, however, was the South Belka Munitions Factory. Or, as it was renamed post-annexation, North Osea Gründer Industries.

Even though their home nation collapsed, the arms manufacturer kept producing weapons, funding coups and stoking international tensions across borders. Belka is “the country which experienced the most growth and direction changes throughout the ACE COMBAT series. As we released more titles in the series, the messages we want to convey through Belka have increased.” Kono goes on to say “I believe that the most complex and serious messages are told in the Belka storyline.” Even if he is reluctant to ground Belka in the real world, the allegory, the deep-seated criticism, and perhaps even an anxiety, of Japan’s mid-century military industrialization, is apparent.

The big bad of the arc of Strangereal’s recent history, depicted by the beloved trilogy of PS2 games and completed by AC7, is just a prelude. Though AC7 ends with a hopeful outlook to the future, one of refugee relief and the return of the first ever international space elevator mission, we know that another war is just around the corner.

AC3 isn’t the only title set in the future. Within a year of the end to AC7’s Lighthouse War, we know the Aurelian War, and other accusations of profiteering and AI drone development, will break out in the 2020 of Ace Combat X: Skies of Deception (2006). And for the next twenty years, as the super weapons of the past era finally decay, another, less fashionable threat will grow until the sci-fi setting for the “Intercorporate War” (itself an AI war in an entirely different way) is set. Evil in Ace Combat isn’t a super weapon or an international standing army, but corporations that propel Strangereal into the future.

“ACE COMBAT is the story of an ace pilot,” Kono writes, “and a story of the human heart.” Furthermore, it’s important the games “show that every story has multiple perspectives, feelings, and ways of thinking, depending on the position of a character.” War is merely a motif, “we nor Mr. Katabuchi even attempted to portray war in a glorified way.” There are immoral officers in every game, government and military leaders get duped all the time it seems, and you, the recurring ace pilot, must persevere.

Except, that’s at odds with the games’ own themes. Kono’s explanation elicits colloquialisms central to American military propaganda: “all sides” and “boots-on-the-ground.” By claiming that the only people who are really equipped to see through all sides of a conflict (notably, an occupied country’s media versus our own) are the individual troops stationed there, we absolve the individual actions of an imperial machine. We can be assured that these grunts, no, these aces would surely make sense out of their officers’ inhumane orders if they came, let alone commit war crimes of their own accord. (There are too many stories to link, here’s a compiled list).

At least, our player character wouldn’t do something so indefensible. But in Ace Combat, all our pilot ever does is fly to someone’s orders. He (and it’s always a he) never sets the objective, never rejects a mission. He just happens to be on the right side of history. Even if there are others, we’re assured ours is correct. And if we bomb civilians or shoot on enemy forces waving a white flag, it’s because there’s still a mission left to reposition our fight to the side of “good.”

Furthermore, Project Aces often flies too close to the very thing their games otherwise set out to critique. Ben Sailer describes for Unwinnable how the games’ fiction starts to fall apart when you consider that in a world where restoring a super-sonic plane is like fixing up an antique car, the “Dassault F2000 Mirage (for example) is a real French fighter jet sold to the UAE, Taiwan and India (three countries in various states of tension with their neighbors).” I asked Kono about their use of real world planes, names, and even countries in descriptions, to which he replied “that would jeopardize what we’ve set up in Strangereal. While we love providing some insights, I don’t want to clarify everything for fans. Fans have the right to imagine, and we believe we have a duty to leave room for fans’ imagination in our storytelling.”

But here’s the thing: Project Aces uses real world planes, which means real world industries that profit off of imperial violence, that make weapons of war, that make those civilian casualties these games want to comment on, benefit socially and monetarily from the games’ successes. Aircraft and weapons manufactured by Boeing, Dassault, Eurofighter Typhoon, Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and Saab are all licensed by Bandai Namco, and the studio worked with the JASDF during development. (The state-owned Russian conglomerate United Aircraft Corporation’s aircraft also feature prominently but do not appear in the credits of AC7). When asked about the studios’ relationship to these companies, a PR person informed me that Kono was unable to answer (this and other) follow-up questions.

Strangereal is a nuanced depiction of imperial violence, and it’s also a plaything. Project Aces makes incredible games that tell interesting stories and aren’t afraid to be “political.” (And while we know little about their labor practices, their response to a Vice interview is promising). But we also can’t, we mustn’t, separate a games fiction from its own politics of creation. To do so would be to betray the story, the artistry, the work. As our timelines begin to overlap, Strangereal is a world we’re flying towards at a supersonic velocity. One that’s set us down a tunnel with no end.

3 thoughts on “25 Years In The Making: The Strange, Real World of Ace Combat”