My Vision is Augmented: Surveillance in Deus Ex: Human Revolution

Science fiction imagines the future based on aspects of the past to show how industrialization changes society. These changes take shape under the material umbrella of technology that affects ways of thinking. Conversely, these immaterial effects influence development of products. It’s an interplay between mind and body. Deus Ex was envisioned in the nineties when flow of information had been changing with the widespread use of the internet, a technology developed by state-funded research and appropriated for wider use by corporations. It’s an another interplay between dualities. Deus Ex explores what it means to be a citizen amidst state and corporate powers, and how an individual’s mind and body is shaped by them.

The center of this is surveillance. Deus Ex fetishizes leather trench coats and sunglasses while embracing the relationship these materials’ production represents. It rejects and embraces corporate and state influence at once as immaterial and material reality. Human Revolution follows Deus Ex’s interest in dualities and strikes in aspects unintended, similar to the original game’s omission of the Twin Towers due to technical limitations. It draws from conflicts and trauma of Detroit city’s past to imagine its future of post-9/11 surveillance state. This is a selective process that erases and overwrites its sense of place and culture to a few vertically twisting and turning streets populated by characters resembling people. It humanizes and dehumanizes, takes people apart to reassemble them and strips places to create non-places. Speculation passes between them to present a perspective through a lens of looking. It is to surveil an interplay between state and corporations and their effects on mind and body. Adam Jensen, Human Revolution’s protagonist embodies this tension between state and corporations as an ex-cop turned corporate security specialist for body-altering corporation Sarif Industries. His body is stretched out like a tapestry to show the effects of conflicting powers.

Surveillance of State and Corporations

Policemen walk the streets of 2027 Detroit and cameras sweep corridors of corporations. Officers issue verbal warnings and cameras start beeping when people enter areas they aren’t supposed to be in. Enforcement follows these warnings in public as well as in private spaces. We experience this lack of differentiation whenever we step in guarded property with the player character. The game world consists of characters who carry arms and those who don’t. Police officers, gang members and security guards act as enforcers, while civilians have no choice but to endure enforcement. Transgressions of other characters remain invisible to us, as we only see the aftermath of enforcement in dead bodies left on the streets and with civilians put to chains. People are isolated from each other by the ever-present but opaque violence of the state and corporations.

Security firms strive to sell and lease equipment, provide manpower and services to whoever they can. An omnipresent and invisible force drives them. Human Revolution envisions such an overwhelming influence of the private security sector that identical cameras sweep public and private corridors. We have to avoid the watchful eyes of these cameras at home and abroad to progress. Cameras shape and evoke a uniform reaction. People in uniforms similarly do. Uniforms are associated with a set of actions, which make us behave in certain ways. People may avert their eyes from authority figures and slow down or speed up when walking past them, for example. Does the uniform make them afraid or do they fear prosecution? Probably both, because the former represents the latter: uniforms prescribe behavior by means of codification and this codification shapes behavior. Some may turn distrustful towards the public once they become aware that they’re being watched by state agents in disguise. Are they afraid of the public or of surveillance? Both, again, since the potential threat of surveillance intertwines with the public.

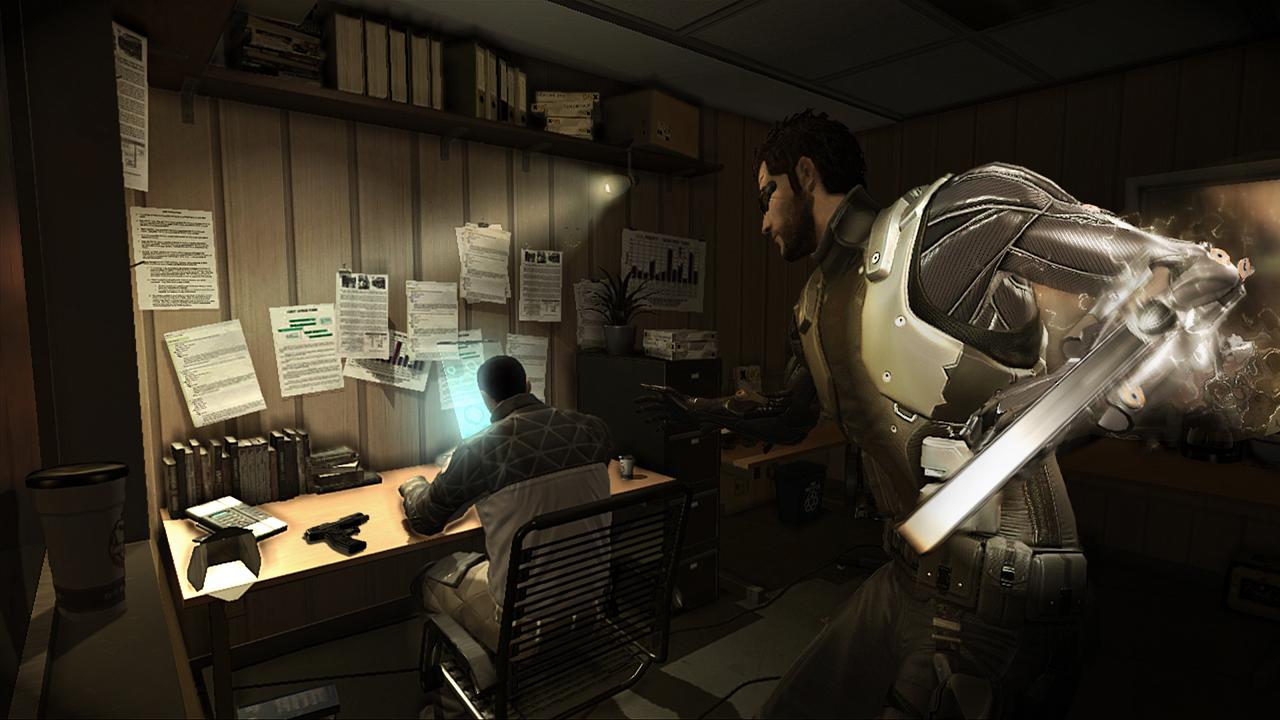

Guards enforce rules with warnings and violence at a global scale without deviation. This enforcement is preceded by assessment of whether the player acts in ways they aren’t supposed to in a specific time and place. Assessment is based on information gathered by ways of looking, hearing and communication. Where do cameras stand within this order? They look, assess the situation, then issue warnings and trigger alarms. Turrets work the same way, except bullets follow assessment. We peek around corners to canvas rooms for danger and duck into cover when we see muzzle flashes to reassess the situation. What do we see when we look? Is it solely driven by the purpose of assessment? We see guards made out of flesh and blood, metal and everything in-between. Our assessment judges what danger their outlook and patrol patterns imply and how they react to our presence. Guards react to sounds and shifting shadows resembling bodies by talking to themselves, perhaps in hopes to warn nearby coworkers and to combat the isolating effects of patrol duty. Cameras emit beeping sounds when moving objects cross their vision. Is it to warn guardsmen or mimic human communication? Bodies of metal and flesh alike talk to themselves and each other. Consider what does a signal mean projected by a camera, displayed on a monitor, seen by a guardsman. These moving images are a recreation of reality that guardsmen trust, since they sound the alarms whether they see threats on monitors or with their own eyes. Machines react to guards in a similar fashion. Does it imply trust, do they look the same way people do? We can’t know, because we see the result of assessment based on looking, while these violent encounters influence our actions, assessment and way of looking.

Surveillance of Mind and Body

How do we think about the act of looking now that we know it’s infused with the lens of surveillance? Human Revolution is an excellent game to explore this question. It opens with a cinematic, introducing some of the more important characters in relation to the protagonist as he occupies the center of the frame. Once it’s over, we take control over the protagonist from a first-person point of view, take our first steps and engage with objects laying around, then we’re stripped of control, except for looking. Jensen’s legs follow a side character as they walk the pristine floors of Sarif Industries. We overhear confidential information as lab assistants approach them, encounter representatives of armed government agencies, while our gaze can feast upon experimental technology. The eye doesn’t differentiate between what is and isn’t confidential, it devours it all, hungry for visual information, while the rest of the body is paralyzed. Looking is entrenched in power as the scene’s change in form further emphasizes it. An alarm interrupts this walk and Jensen’s body is revitalized. He takes out an automatic firearm to investigate. Through the barrel of a gun, bodies are seen as threats made out of flesh and metal, illuminating for seconds in firefights. The intruders are easy to shoot dead, but then a cinematic strips players of power and the whole lab crew is killed under Jensen’s watch, including his girlfriend. The protagonist’s body is crushed to pieces as the intruders throw him around like a ragdoll. His life is saved by being torn apart on the doctor’s table: limbs and muscles separated from the body, bones and organs infused with metal and reconfigured to work as part of a machine. It’s a violent process where body parts are taken apart, thrown away, replaced and reassembled according to the rigid materiality of metal.

The game opens proper after Jensen is ordered back to work before making full recovery. The first words we hear, as players, are the demands of his boss, and the first thing we see of Jensen is his metallic frame shaped like a human body, sunglasses welded to meat and bone closing in on his gaze. Again, we’re reminded of the act of looking. And after the camera rolls around Jensen’s body, it disappears at the back of his head, giving us his vision. His mechanized body calibrates itself, and we’re given access to a mini-map that shows people as moving dots projected in front of his eyes. Augmentations label doors, computers, recognize people and objects we may not know. An object is given a name and an indicator of how Jensen and players can interact with it: use. People are similarly recognized for who they are and whether Jensen and players can interact with them: talk. If the software doesn’t know their name, it categorizes them through an assumed security specialist’s eyes: as police officers and security guards or as gang members, sex workers, vagrants and civilians. Marginalized groups are differentiated from stand-up citizens with degrading labels like “punk, hobo and working girl.” This uniform approach to people, machines and objects stands in parallel with how information is conveyed to a utilitarian button press.

Synthesis of Surveillances

Augmentations modify our body to the effect of how we see and how we’re being seen. Their aim is to improve how we surveil people and machines and to make it more difficult of being surveilled. We may confront their gaze through the cross-hair of a gun, or avoid and deflect it through means of trickery. One augmentations makes it possible to become transparent to the vision of people and machines. It uses energy, just as guns use ammunition. This energy replenishes itself over time to a minimum degree and it can be recharged to full by items that have monetary value in-game. Currency can be attained by thievery, mercenary work and corporate espionage. Energy retains exploitation and violence inherent to money and its use as means to power. Augmentations serve as instruments to disempower the gaze of others and empower our own. Sunglasses encapsulate this function and reflect the multifaceted property of capital. One’s gaze speaks of interests and implies intent. Sunglasses make it possible to infer from gazes while preventing inference from their own. Its name hides this function as it implies cover from the Sun. This hidden property allows for possible denial to use this function in relation to authorities and the public. Who can afford augmentations to use for and against surveillance? Strangers at home and abroad comment on Jensen’s augmentations and the status they carry. And his sunglasses remain embedded to his skull, covering his gaze day and night, during conversations and in combat.

What does it mean for players to look at Jensen through a monitor and control him? We see his actions play out in cutscenes, powerless to alter them, only to possess him through the back of his head and do as we please. The controls are an extension of his limbs: they follow our instructions no matter what. A push to the left and he wobbles left, a press on the sprint button makes his body move faster, his metallic hands swinging in front of our vision. There’s a dedicated button to hide behind cover and see his whole body. It’s a reminder of who we’re control of and also acts as a means to get a better look at the place we’re in, that is: to surveil. But don’t we surveil Jensen as well whenever we zoom out? We look at his positioning to the same utilitarian purpose as we look at cameras, turrets, people and the outline of rooms. Whenever the camera zooms out to show Jensen, his body is safe behind cover. This hides us from others but exposes us to ourselves while surveilling others and ourselves. These paradoxical effects serve as reminders of the power we have over others while being reminded that the same power binds us.

Do we have the power to solve this riddle on our own? Even if Human Revolution implies that we can by giving us power to see and choose how earth-shattering conspiracies unfold, we stroll sterile corporate corridors, barren of life, overhear work-related woes and stare at the exhaust of white-collar labor in endless chains of emails. When Jensen botches hacking, guards and machines mobilize with symbiotic harmony to avert the threat. Civilians are powerless against violence and must turn to guards when exposed to danger. But there’s a lack of immediacy when a person calls out for help in stark contrast with an alarm of a machine that immediately mobilizes bodies of flesh and metal. It makes perfect sense, considering that cameras and turrets are built with the singular purpose of surveillance. They look at corporate floors non-stop and sweep them clean of intruders with laser precision. The cost of this precision is calculated in advance as operational and maintenance expenses. These costs are transparent to the naked eye and corporations can swallow them with ease and without trace. This calculation creates a distancing effect in time and space to create a reductive lens to surveil, then outsources looking to make sure no lens exist capable showing a clear picture. People and machines then appear as abstractions on monitors to be subject to prescribed forces of violence. Jensen’s augmentation arsenal follows the same lack of differentiation between people, machines and objects, except he must bear the brunt of operational, maintenance and improvement costs, as well as the scars they leave on body and soul. Sarif Industries rebuilt Jensen to the means of serving their interest, from which point he is left to his own devices. Corporate guards are treated the same, because once protocol against trespassers are exhausted, they’re on their own against the weaponry of Jensen which tears apart meat and metal the same. Why should it differentiate? Machines originate from replicating human labor to make work more effective with secondary consideration to people struggling under its weight. Deus Ex: Human Revolution, then, isn’t much of a revolution, but rather a speculative vision of industrialization followed to its violent conclusion.