Where are the Mental Health Professionals in Video Games?

As a student of Psychology and an entertainment lover, I’m always interested in discovering how different types of media portray topics of Mental Health. The situation varies depending on your culture, but it isn’t hard to find a lot of stigma regarding these issues. “If you are depressed, it’s because you aren’t focusing on the positive stuff in your life”, “don’t take any medication, you’ll become addictive and you don’t need it”, “just go running for half an hour and you’ll feel like new”.

These are common phrases I’ve been paying attention since I started studying, and I find them more and more dangerous every time. It’s interesting to explore how media tends to show, for example, people dealing with depression. Nowadays, there are films and series that treat them with a lot of respect. Although it’s a animated show, BoJack Horseman is one of my favorite examples of the last couple of years.

Regarding video games, we have the chance to experience unique views at these topics too, with original titles such as Celeste or Gris —just to name a few. However, recently I’ve started wondering if I’ve ever seen any of my future colleagues—or any other professional who works with Mental Health, such as a psychiatrist- in a video game. While the answer is positive, it took me quite some time to come up with examples, and I actually didn’t think any of them were very relatable.

So, I thought about doing a brief research trying to find more representations in this medium, and how “properly” they’re done.

Who are these “professionals”?

In Grand Theft Auto V we are introduced to Michael, one of the main protagonists, during a therapy session. The session works as a clever presentation of the character, because we get to know some bits about his story, his family and how full of anger and angst he is. There’s also a joke based on a stereotype that therapists close their sessions in an arbitrary way. Then the scene concludes and you have a laugh or two. However, this isn’t all. There are six other sessions Michael has with the same doctor after completing certain missions. He also gets emails and calls from him. Moreover, some of the sessions are by phone.

After the second session, one thing is clear: Dr. Friedlander is a parody—like most everything else in GTA. The therapist hears about possible murders and does nothing about it, something that’s decidedly against the APA’s code of ethics. Also, Dr. Friedlander calls Michael a “friend” and “sick,” and asks him for more money after every session. And how can we forget the magic question: “What about your sexual problem, Michael?” During the last session, the therapist abandons Michael and tells him he’s going to have a TV show in which he’ll reveal Michael’s secrets. We, as a player, have the chance to kill him or let him go.

Another example of a mental health “professional” is found in Katana Zero. Here, a psychiatrist appears from time to time, giving a drug called Chronos, which grants special abilities, to the player character. The psychiatrist is quite rude and treats our character fairly badly, so we suspect he’s up to something. It’s a surprise, however, when he turns out to be a secret boss. The fight against him is incredible and memorable—psychedelic at first, and then horrifying as the psychiatrist transforms into an abomination that looks ripped from the mind of Junji Ito.

Then there are titles in which we have some more “fantastic” adaptations of these professions. Take Psychonauts, for instance. Inside this elite group of secret agents of born natural psychics is counselor called Sasha Nein, who runs morally questionable tests. (By the way, Psychonautics is actually a thing). Another example is found in Second Sight, a title in which you control a parapsychologist—someone who studies “paranormal” psychic phenomenons— with psychic powers. Yes, Parapsychology actually exist, but please, don’t ask. Google it yourself.

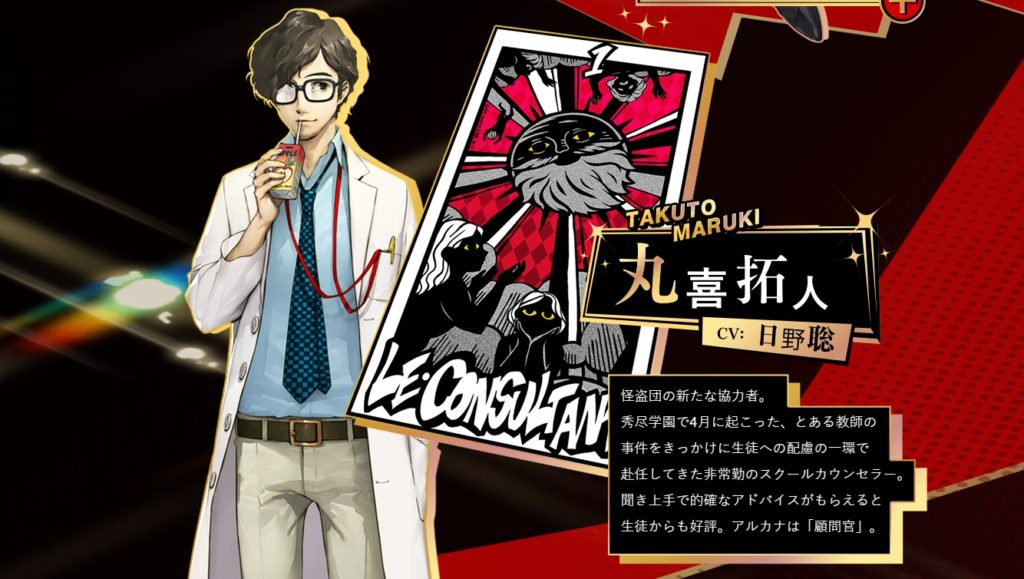

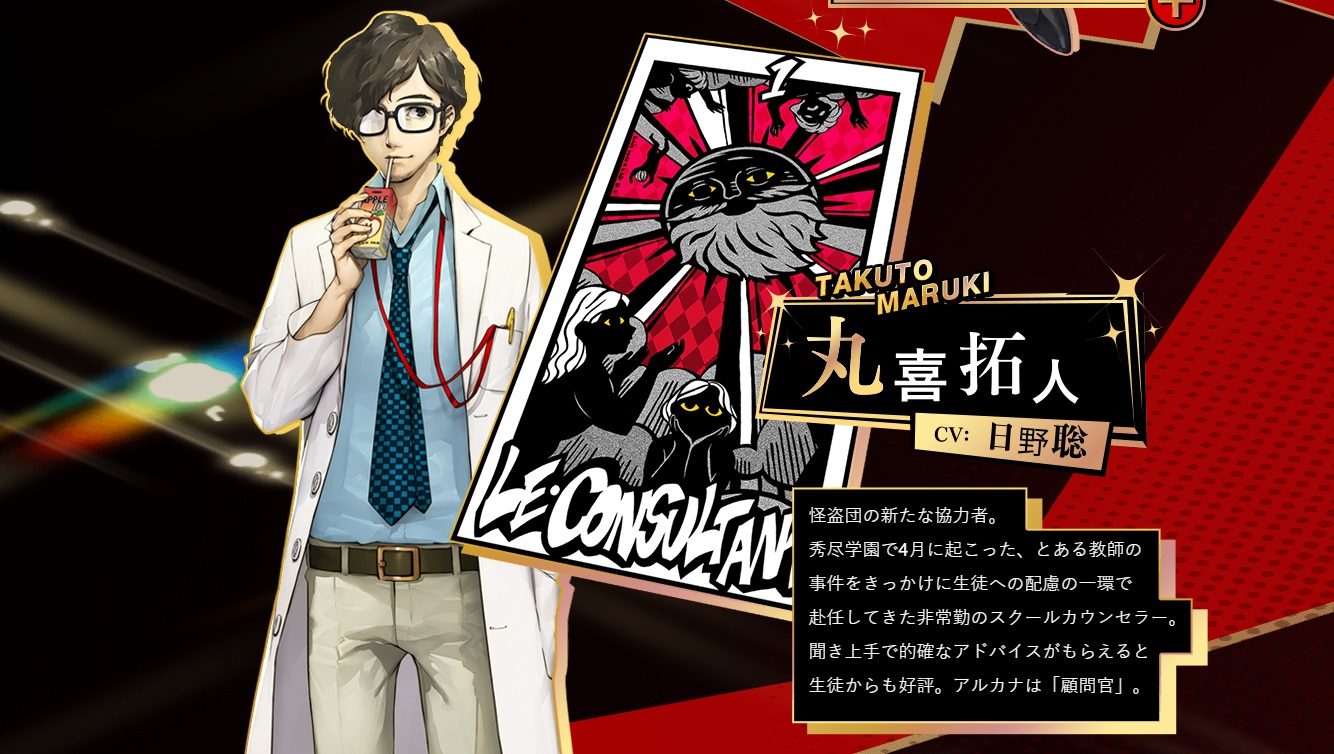

When searching for more recent titles, I found that Persona 5 Royal has a school counselor. Dr. Takuto Maruki is hired at Shujin Academy after the some incident took place. He treats his patients with his own theory, called “cognitive pscience”, which is “the study of people hearts and how they guide their view of the world”. Apart from this strange—but rather fascinating—new therapy, we can see how patient, open mind and kind he is during his sessions. However, there is a twist with him. A big one. I won’t spoil anything for obvious reasons, but his secret is so insane that he makes all the previous examples look like honorable professionals.

The use of a mental health professional has been rather usual in the Horror genre, at least in the last two decades. In Silent Hill: Shattered Memories, Doctor Michael Kaufmann—perhaps named after psychologist James C. Kaufman?— makes you take some psychological tests that will alter how you play the game. Nevertheless, Kaufmann is a member of The Order, the cult of the series. Something similar happens with Until Dawn and Dr. Hill, who’ll make questions during your playthrough and change his appearance depending on what you answer. Other franchises like Manhunt or Outlast uses psychiatrist hospitals or asylums as places full of insanely dangerous people—which is an entirely different topic, but I felt it was worth mentioning.

In all the previous examples but one, the professionals were NPCs. What about a game in which you actually play as psychiatrist? Psychiatrist Simulator might be what I was looking for. Or not. It’s a title in which we, *check notes*, simulate being a psychiatrist. We have to make appointments with our patients and have sessions with them by choosing dialogue options. However, when you actually play i, it feels more like a huge joke. It’s a very limited and rudimentary game that sometimes can be hilarious. Also, it can have a complete lack of tact when dealing with delicate issues.

I could go on for hours with these examples, but you are getting the idea. I couldn’t find a single example that was decently relatable or/and not just a bad dude full of secrets.

Where did this trope come from?

How did we get here in the first place? When we think about mental health professionals in other media, perhaps who first comes to mind is a very handsome cannibal psychiatrist. Or what about the more modern literature creation of John Katzenbach? However, if we want to find more relatable and friendly representations of these professions, we can actually find them in both films and television series. In fact, there are entire series based faithfully on these professions, like “In Treatment”, Brazilians HBO’s “Psi” or the Spanish “El grupo” (“The group”). There’s even an Argentinian series being produced right now with every actor and actress recording themselves at their houses. It’s accurately called “Terapia en cuarentena” (“Therapy in quarantine”).

Then why are the video game portrays so unfortunate?

It is most likely that there isn’t a single answer to this question and that we could aim in very different directions. For example, how well do video games actually represent other values and topics? How many Spec Ops: The Lines are there for every other war shooter? How many games based on modern war conflicts have anything interesting to say, critique or analyze? It’s not the case of the last Modern Warfare, and it isn’t the case of almost any title of that franchise. Do the exercise with any other genre, look at the top sales titles and what they are saying—if they are even saying anything at the first place.

Perhaps we should ask who is making these stories and characters. In doing so, we shouldn’t forget a key statement. The fact that now more than ever we can find deep and complex female protagonists, in-game homosexual couples or even women, people of colour and persons from other sexual identities working in video games doesn’t deny a more prevalent fact: the video game industry is still a industry dominated by white men.

What does this have to do with the article’s topic? Well, a lot. When you write a story or a character, it’s most likely that it will have some of your ideology and values at least in a certain degree, even if the character antagonize your ideas. So if we receive stories only from a certain group and way of thinking, we’ll always gathered more or less the same ideas. Regarding masculinity, concepts and values usually related with “what is to be a man”, “men don’t cry” and other heteronormative discourses will be the norm and affect —or at least try to affect—our own way of thinking.

On another subject, it isn’t the case that there aren’t, for example, psychologists working inside video games or studying them. Real psychologists intervene and help in game development, making titles more “engaging” (and sometimes “addictive” too). There are professionals asking and investigating how video games could work as therapy or how they affect us cognitively. And what about the mental health of the people actually making games? Today we know more than ever about the labor exploitation workers deal with in the industry. However, I ask again: Where are the mental health professionals in video games?

Don’t get me wrong: I don’t think this “the most urgent” issue in the industry right now and that we should put all our “forces” to solve it. However, defining urgencies can leave us in front of a paradox. If we know that crunching is a more pressing issue but we don’t work any changes, then neither the crunch or the representation will have a solution. It’s an unrealistic approach. While it’s logical to have priorities and “distribute” the work towards a better future, that doesn’t mean we should avoid certain problems because there are others more demanding.

Why this representation “could” matter

Generally, representation in media is a harder subject that you might initially realize. As part of her research into representation and identity in video games, the game studies scholar Dr. Adrienne Shaw wrote a 2010 paper “Identity, Identification, and Media Representation in Video Game Play: An audience reception study.”

Shaw concludes that “identification with characters is not always relevant or a reason for playing video games,” and that “playing as a character or with an avatar does not imply necessarily identifying with that character or avatar.” Furthermore, we must consider the ways companies “create” representation, how this is influenced by the market, how players interact with these products, and the dichotomy between realism and fantasy. If representation means a path in creating more “realistic” video games, treating them only with seriousness, it can affect the actual fun and joy of playing them. Why, then would we care? However, Shaw’s research doesn’t deny the importance representation can have for individuals, or how having a male white heterosexual protagonist as the “expected setting” reduces the room for diversity.

But what does any of this have to do with this article’s title? It has to do with the social imaginary—the set of values, symbols and other concepts that create our view of society. Mental health treatment is still treated in many countries around the world with a sense of extreme stigma. Frequently, people who go to therapy are labeled “crazy” or “weak” for being “dependent” on medication. These largely false arguments create rejection and someone who could want to ask for help, or even more important, need the help, wouldn’t do it because of fear of being discriminated against or falling into an “unwanted category.” It’s ironic that this happens even in my home country of Argentina, a nation with the highest number of psychologists per capita.

Institutions and media shapes our social imaginary of any topic we can think of. If video games can, for example, help a young person feel more confident about starting therapy or having medication because they saw it in a protagonist or an NPC, I celebrate it. Of course, the process isn’t so simple or linear. We can dive into Shaw’s work and find more questions than solutions. But the mere existence of these representations give visibility to the professionals and it gives them life. It doesn’t matter if almost none of the aforementioned examples are realistic representations. Video games can and should be creative when possible. Usually, we can distinguish between fantasy and reality; we can interpret that Michael’s therapist is a parody of a bad mental health professional. As long as there aren’t only negative depictions about professionals—which would lead to harmful stereotypes—these representations could be a step in the right direction.

Some last thoughts

But is the portrayal of these professions the only way we can assure topics of mental health are “correctly” being taken care of? Of course not. What makes video games so unique as a medium is that they have their own approach to different topics and issues. Not only in the possibilities of storytelling but also how they interact with the player. Interaction is one of the key elements that separates this medium to other forms of entertainment. Video games make you participate, allowing you to identify with whoever or whatever is on screen. When we do so, we start to share the emotions and thoughts of our characters. Nowadays, more and more interesting new titles are innovating when it comes to the tools, experiences, and depictions of mental health. We could argue that creating more of these special experiences with affecting mechanics is a more necessary and interesting approach than just portraying “legit” professionals.

Also, it goes by without saying that not every video game should have a strong and respectful message of mental health or a faithfully representation of a mental health professional. They have the right to be silly, unrealistic and just fun. However, this doesn’t mean that there shouldn’t be at least a few legit representations. We are speaking about a medium that’s by far the most lucrative form of entertainment, and I couldn’t find an accurate representation in any way. Furthermore, it seems that the medium tends to demonize the profession and we already learnt the potential negative effects of that demonization.

At the end of the day, I just want people to have whatever aid they might need and have the will to ask for it, without any stigma around them.

Loved this thoughtful review.

“Eliza” is a visual novel-style game in which the player starts out as an employee of a Silicon Valley tech corporation that has created a virtual therapist.

The corporation has determined that client want face to face interaction, but that the best therapy is generated by AI. Therefore, you as an employee sit in a room with the client, reading what the AI tells you to say. It’s a fascinating tension: you are driven to genuinely help these people, but you are basically a puppet of an unfeeling algorithm. It removes the human element from the humanity of caring. Definitely worth a playthrough.