The Storm-Cloud of Death Stranding

In his 1884 series of lectures The Storm-Cloud of the Nineteenth Century, painter and art critic John Ruskin announced the appearance of a new kind of cloud. This “plague-cloud” was (among many different interpretations) the first effect of the Industrial Revolution on the weather, the first sign of the present climate change. It was never clearly described by Ruskin, but we can see a strikingly similar cloud in Kojima Productions’s Death Stranding, and we can insert Kojima’s last work into a tradition of art that looks at clouds, skies, and atmospheric events, depicting our climate and the often catastrophic effects of climate change.

Death Stranding is set in a near-future America after the titular event erased the boundaries between the world of the dead and the world of the living. Like Ruskin’s 19th century, the Death Stranding event brought a new kind of clouds, the “chiral cloud.” Chiral clouds are influenced by substances (“chiralium”) that come from the world of the afterlife and shower timefall, rain that accelerates time, making living beings grow older and turning buildings into rust. With chiral clouds and timefall came the BTs (Beached Things); when and where timefall rains down invisible ghosts trespass into our world, looking for humans, and when they touch someone their dead antimatter interacts with the matter of the living world, triggering a giant explosion known as a “voidout.”

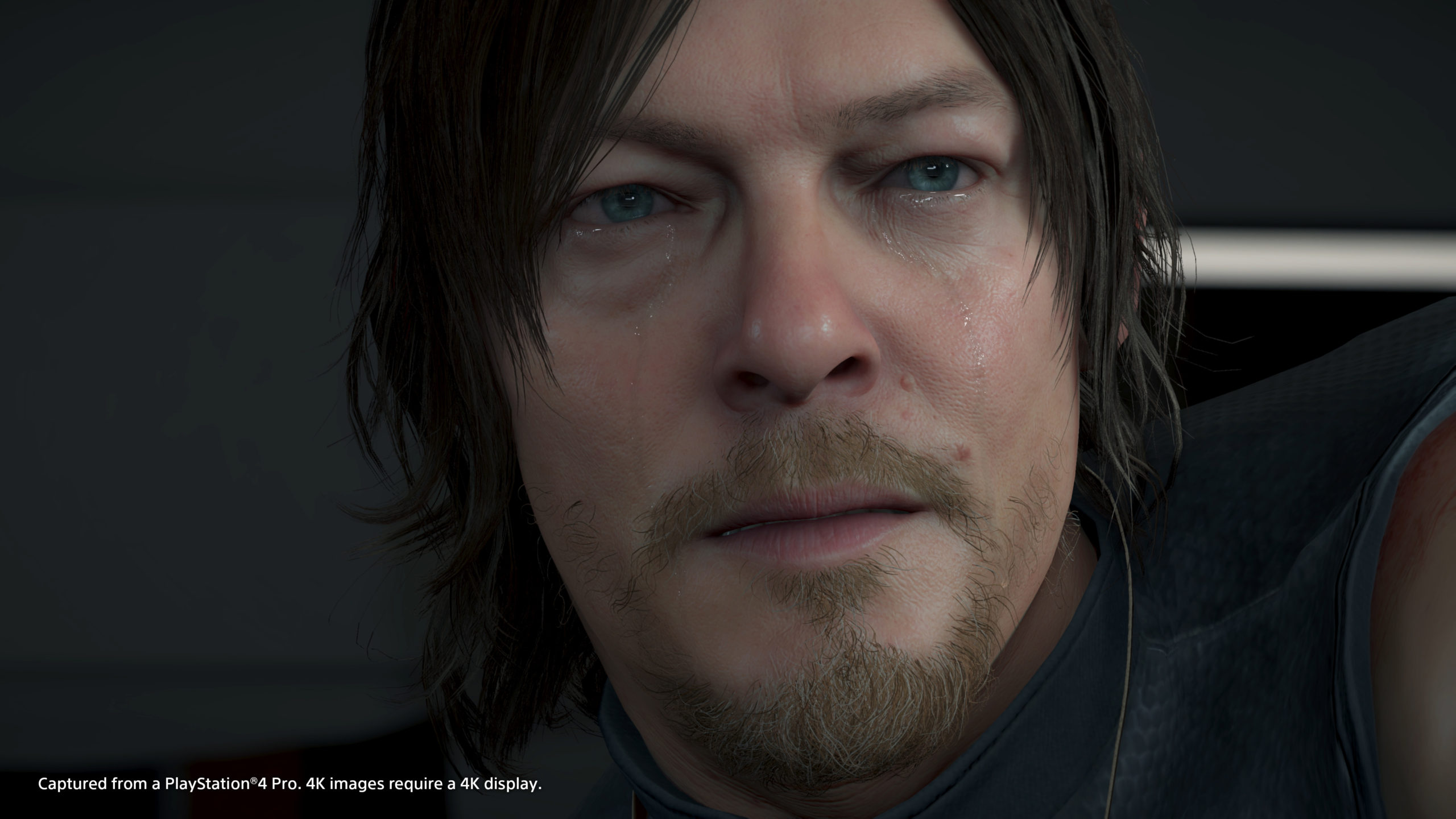

The player is Sam Porter Bridges, a delivery man that has special abilities linked to the world of the afterlife and takes advantage of these powers to survive timefall, BTs, and attacks from other humans. Fear of BTs and timefall forced people to live underground, in isolated cities where they wait for their resources to be delivered at their door and communicate with the outside world only via holograms. Sam has a double task: he must connect cities and outposts by transporting packages to and from them and he must connect them to the chiral network, a sci-fi internet that instantly transfers and shares data through the afterlife itself.

As Kojima repeatedly claimed, “connection is the theme of the whole game,” and clouds represent this connection: chiral clouds connect to the afterlife and another cloud, the digital cloud of the chiral network connects people through the afterlife. “The cloud acts as an interface: between heaven and earth, between user and data,” writes Natalie Koerner about the digital cloud of our real world. Only few video games make players look at their skies and their clouds as much as Death Stranding does, because cloudiness and inverted rainbows mark the dangerous places where BTs roam. At a certain point, players even unlock a weather forecast system.

But humankind has always looked to the sky. The sky was the dominion of gods and divine forces, and thus its phenomena were able to unveil their will and foretell the future and its apocalypses. Skies were contemplated, studied and represented in art. Weather forecasts became an obsession of the military apparatus and shaped the birth of informatics.

From the moment climate history began its development as a discipline, climate historians have been looking at past observations, searching for proof of the climate of the past and the changes it experienced. Complete climate reports were lacking but diaries, ship logbooks, engravings, and paintings were important evidence of what the world used to look like and how artists observed extreme climate events. For example, comparing engravings and drawings with recent photographs allowed scholars to evaluate the shrinking of glaciers from the 14th century, and comparing Veronese’s, Canaletto’s and Bellotto’s paintings with present-day images allowed Dario Camuffo to measure the increase of water levels in Venice before regular records began to be kept in 1872.

The representation of skies and clouds in paintings was studied, too. The trend of snowy and winter landscapes in 17th Dutch art have been connected to the so-called “Little Ice Age,” a period of lower (but fluctuating) temperatures caused by a combination of factors, like a decline of solar radiation and variations in the orientation of Earth’s axis and in the ocean-atmosphere system. The Little Ice Age started in the 13th century and ended during the 19th, and even though average cooling was probably moderate, its effects were global and long-lasting. Lamb’s Britain’s Changing Climate, published in 1967, used the cloudiness of skies in Dutch and English art to study the variations of summer weather in England. Then, in 1970’s Climate in Art, Hans Neuberger examined blueness of sky, visibility, cloud coverage, and types of clouds in 12,000 paintings from 1400 to 1967 and from 41 different museums in the U.S. and Europe. Neuberger found out that darkness and cloudiness increased over time with the development of the Little Ice Age, before the trend reversed at the end of this period, around 1850. Painted skies became increasingly less blue even after the end of the Little Ice Age, as an effect of industrialization and air pollution.

More recently, two research papers—Atmospheric effects of volcanic eruptions as seen by famous artists and depicted in their paintings (2007) and Further evidence of important environmental information content in red-to-green ratios as depicted in paintings by great masters (2014)—led by C. S. Zerefos, explored how natural climate change caused by volcanic eruptions has been represented by painters and how paintings can be used to retrieve information on the composition of the past atmosphere. Volcanic eruptions cast aerosols (solid and liquid particles suspended in the air) into the upper layers of Earth’s atmosphere, known as the stratosphere. The effects of these eruptions can last for up to three years and can be seen worldwide.

Since the color of the sky is the result of the interaction between light and the molecules of the air, volcanic aerosols influence the resulting colors and produce blood-red sunsets and afterglows. Light is composed of the whole spectrum of colors, from violets and blues to reds, and each color corresponds to a different wavelength of the electromagnetic wave of light. In the phenomenon called “Rayleigh scattering,” particles that are smaller than the wavelength of light (like nitrogen and oxygen, the two main molecules in our atmosphere) scatter short wavelengths (blues) more than long wavelengths (reds). That’s why the sky is blue: the blue wavelength is scattered the most and deflected so that it reaches our eyes. And the sky becomes orange or reddish during sunrises and sunsets because the sun is lower on the horizon, meaning sunlight takes a longer path through the atmosphere and loses its blue wavelength in the process.

Volcanic eruptions emit sulfur dioxide that is converted by air humidity into droplets of sulfuric acid and forms layers in the stratosphere that increase the scattering of light, thus making skies redder. The increase in the scattering also reduces the light that reaches the ground, cooling the surface of Earth. Nowadays, the small particles produced by anthropogenic pollution act in the same way as the aerosols emitted by volcanic eruptions, enhancing the red colors of sunsets in our cities. But heavy pollution can subdue sky colors and their brilliance, too; bigger pollution particles in the troposphere (the lowest layer of our atmosphere) do not respect the Rayleigh approximation, so the scattering is not selective anymore, reducing the total amount of light reaching the ground.

Christos Zerefos’s team calculated the chromatic ratio between red and green colors (the “redness”) of sunsets painted by artists like Claude Lorrain (1600–1682), Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851), Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840) and Edgar Degas (1834–1917) between 1500 and 2000. As observed, this ratio dramatically increases—and skies become more red—in paintings that were realized in the years following a volcanic eruption. For example, the explosive eruption of Tambora in April 1815, combined with the waning of the Little Ice Age, caused crop failures and contributed to a cloudy, cold, and wet year known as the “year without a summer.” 1816 was one the coldest of the last 400 years in the Northern Hemisphere, with endless rainfalls, food riots in Central Europe, migrations caused by famine in North America and droughts in India (the cold caused changes in atmospheric circulation and probably delayed the monsoon rains). But Tambora’s eruption also influenced the sunsets painted by Turner in 1817 and 1818 (did Turner inspire Bloodborne’s apocalyptic fire red sunset?) and the “smoky” and “crimson” sunset described in John Clare’s poem A Beautiful Sunset in November. It also defined the dark mood and atmosphere of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s Frankenstein and Lord Byron’s poem Darkness, both penned during the summer of 1816. The crisis triggered by Tambora’s eruption and the fact that its effects were painted by an unaware artist in London clearly show the global impact of climate and climate change on human systems. In Turner’s case, we can even comprare paintings realized before and after an eruption: the red-to-green ratio is 1.14 in his 1828 work The Lake, Petworth, Sunset, then 1.76 in his 1833 Sunset, painted two years after the eruption of Babuyan. Zerefos’s researches showed an increase in the red-to-green ratio during the industrial revolution, too; as previously stated, anthropogenic pollution can act in similar ways as volcanic aerosols.

Even the red sky in Munch’s The Scream has been attributed to the effects of a volcanic eruption. Although it’s possible that the 1893 painting was a reminiscent of a volcanic sunset (maybe caused by Krakatoa’s 1883 eruption), other theories have posited that The Scream could either have been influenced by the sighting of rare nacreous (mother-of-pearl) clouds (polar stratospheric clouds) or have no direct relationship with atmospheric phenomena. But Krakatoa’s eruption, and the sunsets it produced, were immortalized in poems and texts by Alfred Tennyson, Robert Bridges, Gerard Manley Hopkins and Algernon Charles Swinburne, and in William Ascroft’s pastel sketches.

Maybe surprisingly, volcanic eruptions and the variations of medieval climate left their traces on Asobo Studio’s A Plague Tale: Innocence and its clouds: its devs claimed that the lighting of the game was inspired by Claude Lorrain’s red skies, which were in turn influenced by the volcanic eruptions of Awu in 1641 and Katla in 1660. So, when we look at A Plague Tale’s skies we are perhaps looking at skies that represent the consequences of climate change, albeit not human-caused. This also applies to the historical setting of the game—A Plague Tale is set in a fantasy representation of the outbreak of plague in Europe from 1347 to 1353, and climate was one of the contributing factors of the epidemic. At the start of the 14th century (around the beginning of the Little Ice Age), heavy rain caused crop failures, which in turn caused the Great Famine of 1315 to 1317, and famine is known to weaken immune systems of the population. Unstable climate drove the waves of the epidemic, too, killing rodents after periods in which rats had experienced a surge in population and leaving their plague carrier fleas in search of new hosts.

A representative of Asobo told me that they didn’t know the origin of Claude Lorrain’s skies. “The team did not know about Lorrain’s context of a volcanic eruption” Aurélie Belzanne wrote me via email. In a certain sense, the developers were as unaware as Turner that they were depicting “volcanic sunsets.” A Plague Tale: Innocence is a story about children and young women and men surviving in a quasi-apocalypse (the supernatural plague) caused by adults in increasingly foggy, stormy, and almost poisonous weather; clouds and atmospheric phenomena are one of Asobo’s most effective tools to set mood and tone. The sunny sky of the prologue (with an incoming storm on the horizon). The rain during the escape of the protagonists from their home after being attacked by the Inquisition. The warm, red and hazy sunsets of the calmest moments. The fog of the battle ground filled with corpses. The volcanic sunset of the battle with the Inquisition in the Château d’Ombrage. The stormy clouds of the ending moments. But the game was not meant to be a story about climate change. The Asobo rep told me the team wanted to talk about “family bonds,” although they “all feel very much concerned about” climate change. However, the elements—the rats, the red sunsets inspired by Claude Lorrain, the weather—they used to tell this story about children fighting against apocalypse, and the fact that the game was published in 2019 when the public interest in climate change reached an all-time high, contribute to make A Plague Tale: Innocence look like a medieval Fridays for Future.

Turner’s paintings don’t show only the effects of volcanic eruptions: they show the first effects of anthropic action on skies and clouds, too. In his views of London and Leeds, Turner depicted cities emerging from fog and smoke. John Ruskin and his father were avid collectors of Turner’s paintings, and the author of The Storm-Cloud of the Nineteenth Century used to keep Turner’s watercolors hanging in his bedroom. Ruskin loved, above all, the skies and the clouds painted by Turner and his depiction of atmospheric effects, and he was a real cloud nerd: Ruskin was part of the Meteorological Society of London and wrote Remarks on the Present State of Meteorological Science (published in 1839, when he was 20). In his magnum opus, Modern Painters—five volumes, published between 1843 and 1860, that started as a defense of Turner’s work—he says that landscape painting is “the service of clouds.” He even included a perspective study of clouds in the fifth volume.

The Western history of the representation of clouds and skies goes hand in hand with the history of landscape painting. Early medieval painters were not interested in natural scenery (just think of the golden and empty backgrounds of Byzantine art), and clouds were mostly decorative. In his Modern Painters, Ruskin himself comments that, “with [the old masters], cloud is cloud, and blue is blue, and no kind of connection between them is ever hinted at. The sky is thought of as a clear, high material dome, the clouds as separate bodies suspended beneath it.” It’s interesting to note that clouds are sometimes similar in early video games: clouds in Super Mario Bros. are not depiction of actual clouds, they are either decorative motives that recycle the same sprite used for the bushes or solid vehicles for one of Mario’s enemies, the Lakitu, the video game cloud putto. “The medieval never painted a cloud but with the purpose of placing an angel upon it,” Ruskin claims in Modern Painters, and Super Mario Bros. never painted a cloud but with the purpose of placing a Lakitu upon it.

As Huber Damisch writes in 1972’s Theory of /Cloud/, clouds were symbols of unrepresentability itself during Renaissance; painters were unable to bend them to the rules of perspectives, so clouds became signs of what can’t be depicted. Clouds are volume, space, heaven, illusion, and as such they both are opposed to the flatness of terrestrial perspective projection and they define it as the realm of humankind and reality. True landscape paintings began with Joachim Patinir (1480–1524), Giorgione’s The Tempest (c. 1508), Albrecht Altdorfer’s View of the Danube Valley near Regensburg (c. 1520), and Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s The Hunters in the Snow (1565). Later, 17th century Flemish and Dutch artists were arguably the first to represent realistic cloudscapes.

Ruskin lived in a period of increasing interest in meteorology, nourished by the advent of flight at the end of the 18th century and by the 1783 eruption of Laki in Iceland and its catastrophic consequences in the Northern Hemisphere. But, as we said, skies have always been the subject of science and philosophy. We can find attempts to predict weather in Ancient Egyptian, Babylonian and Chaldean texts, and during the Shang Dynasty Chinese scholars used to keep weather journals. Thales of Miletus (c. 625–c. 547 B.C.), the first natural philosopher of Ancient Greece, showed a particular interest in meteorology and in the water cycle (in fact, he considered water the principle of everything). Then Aristotle (384–322 B.C.) and his school explored the topic in the treatise known as Meteorology (the 4th century B.C.), which discussed the formation of clouds. Leaving aside the early Christian period when God’s will was the explanation for everything, Aristotle’s Meteorology was the base of Western meteorology till René Descartes (1596–1650) published his Discourse on the Method, accompanied by the meteorological essay The Meteors (1637). For Descartes, the apparently unpredictable clouds were the perfect test bench for his scientific method.

The history of the birth of modern study of clouds is described in detail in Richard Hamblyn’s The Invention of Clouds: How an Amateur Meteorologist Forged the Language of the Skies (2001). In 1803 Quaker and chemist Luke Howard (1772–1864) published his lecture On the Modifications of Clouds, the basis of our current taxonomy system. Clouds were divided into three main groups (or “modifications”): cirrus, cumulus, and stratus (high fog). These categories could be combined and modified into four more groups: cirro-cumulus, cirro-stratus, cumulo-stratus, and cumulo-cirro-stratus or nimbus (the rain cloud).

Howard was not the first to attempt a classification of clouds, but his forerunners had tried to record clouds following their ever-changing shapes and their color, while he understood that they were the dynamic manifestation of atmospheric processes: the general shape of a cloud is not a matter of chance but depends on altitude, temperature, humidity, pressure, winds, and the presence of particles in the air. Clouds are formed when rising water vapor cools down and condenses to suspended frozen crystals or water drops on a condensation nucleus. These nuclei (small particles that, as previously stated, are called “aerosols”) are usually of natural origin: ocean salt, fragments of soil, volcanic ashes. Human-made pollutants can act as condensation nuclei and increase cloudiness, but recent studies have argued that heavy pollution can also inhibit the formation of clouds, because it blocks sunlight and cools the Earth’s surface.

On the Modifications of Clouds became unexpectedly popular, inside and outside the Quaker and scientific communities, and influenced artists. Howard’s classification was the basis for Percy Bysshe Shelley’s 1820 poem The Cloud, and it was also admired by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, who publicly defended the use of Latin to denote the different categories and in 1817 adapted On the Modifications of Clouds into a series of poems. English painter John Constable (1776–1837) used to own the second edition of Thomas Foster’s Researches About Atmospheric Phaenomena (1815), which contains a summary of Howard’s taxonomy, and during his stay at Hampstead Heath in the summers of 1821 and 1822 he realized more than one hundred cloud studies. It is no coincidence that one of the most famous Constable scholars was a meteorologist: John E. Thornes, writer of John Constable’s Skies: A Fusion of Art and Science (1999).

Howard’s taxonomy, while expanded and modified in the following years, is still used today, but clouds remain symbols of unpredictability. They pose a dilemma for climatologists, too. Clouds are why different climate models predict different outcomes for climate change; they can shield the Earth from sunlight and cool the surface, but they also can trap heat and contribute to global warming, and their long-term effects on global climate are difficult to predict, simulate, and include into models.

In February 1884 John Ruskin delivered his two The Storm-Cloud of the Nineteenth Century lectures and claimed that he had observed new clouds that were absent in the past: “plague-clouds” brought by a “plague-wind.”

“The sky is covered with grey cloud;—not rain-cloud, but a dry black veil, which no ray of sunshine can pierce; partly diffused in mist, feeble mist, enough to make distant objects unintelligible, yet without any substance, or wreathing, or colour of its own,” he writes. Ruskin describes a continuous spell of bad weather accompanied by a ceaseless “wind of darkness” that feverishly drags smoke-clouds that blanch the sun, with black fog and rainfalls that rot grass, flowers, and fruits. “By the plague-wind every breath of air you draw is polluted.” This time, the observed weather was not the consequence of a volcanic eruption (Krakatoa erupted in 1883 and Ruskin dates the first sightings of the plague-cloud to 1871). Instead, it was the first visible effect of anthropic action on European skies, the first clouds created by humanity and the Industrial Revolution.

Anthropogenic clouds are common nowadays. “Homogenitus” and “homomutatus” were introduced as cloud classifications in the 2017 edition of the International Cloud Atlas to describe clouds developed “as a consequence of human activity,” like those generated by industrial plants and aircraft condensation trails. Distrails (“dissipation trails”) and fallstreak holes (“cavum” in the 2017 edition of the International Cloud Atlas) are gaps formed when aircrafts pass through clouds. Noctilucent (“night shining”) clouds (or “polar mesospheric clouds”) are rare clouds formed above the stratosphere, and since they were never observed before the end of the 19th century they could be anthropogenic.

The Storm-Cloud of the Nineteenth Century was ill-accepted by its audience. The general concept of anthropogenic climate change was not the main problem, because the idea that humankind could influence climate (for example, through deforestation and cultivation) has been mostly accepted since the Age of Enlightenment, even though it was usually seen in a positive light: humans were able to manipulate, improve, and regulate the environment and climate according to their needs. But Ruskin refutes that the plague-cloud could be merely caused by human pollution: the storm-cloud of the 19th century is, above all, the result of a moral crisis. This is what sounded strange to Londoners, who thought either that Ruskin was going crazy (and in fact his mental health was actually deteriorating in those years) or that he was just an old man yelling at a cloud. “It looks partly as if [the plague-cloud] were made of poisonous smoke,” he writes in a letter addressed to British workmen in 1871, later quoted in The Storm-Cloud of the Nineteenth Century. “Very possibly it may be: there are at least two hundred furnace chimneys in a square of two miles on every side of me. But mere smoke would not blow to and fro in that wild way. It looks more to me as if it were made of dead men’s souls—such of them as are not gone yet where they have to go, and may be flitting hither and thither, doubting, themselves, of the fittest place for them,” referring to the victims of the then-ongoing Franco-Prussian War.

For Ruskin, environmental pollution and the plague-cloud were symptoms of the same moral disease. “When everybody steals, cheats, and goes to church, complacently, and the light of their whole body is darkness, how great is that darkness!” he writes in another letter, in 1876. “And that the physical result of that mental vileness is a total carelessness of the beauty of sky, or the cleanness of streams, or the life of animals and flowers: and I believe that the powers of Nature are depressed or perverted, together with the Spirit of Man; and therefore that conditions of storm and of physical darkness, such as never were before in Christian times, are developing themselves, in connection with forms of loathsome insanity, multiplying through the whole genesis of modern brains.”

Even in The Storm-Cloud of the Nineteenth Century Ruskin explicitly argues that causes of and solutions to the plague-cloud are moral: “What is best to be done, do you ask me? The answer is plain. Whether you can affect the signs of the sky or not, you can the signs of the times. Whether you can bring the sun back or not, you can assuredly bring back your own cheerfulness, and your own honesty. You may not be able to say to the winds, ‘Peace; be still,’ but you can cease from the insolence of your own lips, and the troubling of your own passions.” Ruskin still saw clouds (and Nature in general) as the medium between man and God, and the fact that humankind could manipulate this divine and celestial realm, this natural manifestation of God’s will and beauty, was a sin. “Pollution… is an outward and visible sign of an inward and spiritual disgrace” writes Brian J. Day in The Moral Intuition of Ruskin’s “Storm-Cloud,“ and the word “pollution” itself had only a religious meaning (it was a “sacrilege,” a profanation of a sacred place) prior to the 19th century.

“Ruskin turns back to an age when the sky was a place of portent, when atmospheric changes heralded not merely a change in the weather but divine judgement,” explains Jesse Oak Taylor in Storm-Clouds on the Horizon: John Ruskin and the Emergence of Anthropogenic Climate Change. “In so doing, he helps us to understand a core conceptual problem posed by anthropogenic climate change: it does not simply alter the physical processes of the climate; it changes what climate is, insofar as it no longer lies (if it ever did) beyond the scope of human history. Where meaning in the skies once bespoke the will of God, it is now bequeathed by the effluence of human affluence.”

Nowadays a combination of global warming, ocean acidification and global homogenization of flora, fauna and diseases (caused by globalization and acceleration of transports) is bringing us to a mass extinction, the sixth one since the rise of life on Earth. And Ruskin’s intuition was correct: this is a moral crisis. “Climate crisis is not just about the environment,” Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg, German climate activist Luisa Neubauer, and Santiago Fridays for Future coordinator Angela Valenzuela write. “It is a crisis of human rights, of justice, and of political will. Colonial, racist, and patriarchal systems of oppression have created and fueled it.”

Scholars have argued that the Columbian exchange—the transfer of plants, animals, people and diseases between the continents during the 15th and 16th century and the European invasion of Americas—was one of the contributing factors in the global cooling period known as the Little Ice Age. Diseases imported by European invaders killed native populations, and so wild plants overran the once-cultivated and now-untilled fields, increasing the consumption of carbon dioxide. It’s possible that reforestation of the Americas in the 16th century depleted so much CO2 that it weakened the greenhouse effect and partly contributed to global cooling. Some ice cores actually show a sharp decrease of atmospheric CO2 at the beginning of the 17th century. That’s the meaning of our geological age, the “Anthropocene”: we left traces inside Antarctic glaciers, among geological strata, and in the atmosphere. Our history is now part of the geological history of Earth. Other research has offered different explanations for the decrease of CO2 in the 17th century, and there are still many unanswered questions. What about the effect of mass deforestation in Asia? What about the effect of newly imported animal species on reforestation of the Americas? What was happening in Africa? Still, it’s possible that when Dutch and Flemish painters painted their winter landscapes in the 17th century, they were also depicting a genocide.

Kojima wasn’t directly influenced by The Storm-Cloud of Nineteenth Century; as the Japanese director explained, the harmful rain of Death Stranding was inspired by the 1975 horror movie The Devil’s Rain. But the similarities to The Storm-Cloud of Nineteenth Century are striking: dark clouds linked to the dead, rainfalls that kill and rot, and a desperate, apocalyptic atmosphere (“the idea of ecological disaster is an Ur-Angst, a primeval anxiety,” claims Doris Rohr). What should be interesting to us is that, beyond these superficial details, both in Death Stranding and The Storm-Cloud of the Nineteenth Century a climate crisis is first of all a moral crisis, and Kojima’s chiral cloud and Ruskin’s plague cloud have the same metaphorical origin in the inability of humans “to be kind to others.”

Death Stranding’s America was divided even before the Death Stranding event: its supernatural division is explicitly an allegory for our age, as if our divided humankind caused the Death Stranding. “This is about an era of individualism,” Kojima told The Guardian. “Everyone is fragmented, in America or Europe, but at the same time we’re connected by the internet. This magical technology should have made people happy, but we’re battling each other.” Kojima shared similar ideas in other interviews, describing Death Stranding as a reaction to Trump’s America, Brexit, and online violence. Our world is divided, so he wanted to make players “relearn to be kind to others.” Death Stranding is mostly a single-player experience, but players can asynchronously share items, packages and equipment with each other, use buildings left by other members of their server, and cooperate to build bigger infrastructures like bridges and roads.

Kojima doesn’t ignore the physical and environmental consequences of the digital age, either. Our digital cloud may look ethereal, but it’s actually made of polluting infrastructures and data centers: in 2019, digital communication was estimated to constitute more than 3 percent of total energy consumption and 4 percent of total greenhouse gases emitted during 2020. In the wake of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, the figure is likely to be even higher: internet usage has surged, while other sources of greenhouse gas emissions have plummeted. In Death Stranding, the chiral network is created through (spoiler!) literal human sacrifices and further connects America to the afterlife by weakening the boundaries between the dead and the living, bringing storms and opening the gates to the “Last Stranding,” the sixth extinction. A mass extinction heralded by clouds.

Humankind has always looked at the sky. In its cloudscapes, humans have seen apocalypses. At first, apocalypses were signs of divine will, effects of volcanic eruptions and ice ages. But when humans began to influence climate and skies and to understand this influence, they began to see themselves in the apocalypse. They saw themselves in the Little Ice Age, they saw themselves in the smog of London and in the new clouds they were creating. The word “chiral,” used in Death Stranding for everything related to the world of the dead, marks something that’s not exactly identical to its own mirror image, like our hands: our left hand is the mirror image of our right hand, but the two hands can’t be superposed (in fact, “chiral” comes from the Ancient Greek χειρ, for hand). In Death Stranding, the afterlife is a mirror image of our world and the dead are a mirror image of the living. Its chiral clouds are mirrors. Like Ruskin’s plague-cloud they show us ourselves reflected in climate change and apocalypse.