A Man Chooses: On Subject Delta, the Avatar Character, and Player Embodiment

The Bioshock franchise is one that likes to flirt with the idea of choices and how they impact the world around us, but usually these narratives fall flat since these games are on rails. But that’s not the case for Bioshock 2’s protagonist, Subject Delta. While Delta is comparable to his predecessor Jack in many ways, there is one defining characteristic that causes him to stand out: Delta makes choices, and those choices affect how others perceive both him and the world at large. While Delta never speaks, we never see his face, and we don’t even know his real name, he is given far more agency than Jackthrough simple, albeit slightly hamfisted, choices. It is through these choices you are able to decide just what kind of man Delta is and embody it.

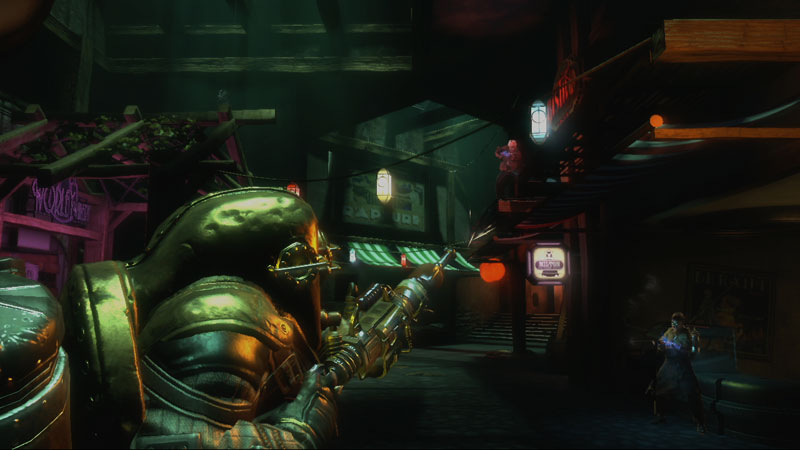

Bioshock’s first two installments both feature main characters who are more or less blank slates. Jack, while the son of Andrew Ryan, doesn’t have much in the way of a personality, and his only defining physical feature is his iconic chain tattoo. The sequel’s protagonist, Subject Delta, is fairly similar. He was a man who made his way to Rapture somehow and ended up being imprisoned on suspicion of being a spy. He was called Johnny Topside, but that’s the closest we ever get to a name beyond Subject Delta. Since he’s in a Big Daddy suit for the entirety of the game, Deta’s appearance is a total mystery. But there is one vital difference between them: Delta’s story is less on rails as he’s left to decide the fate of a few different enemies.

Whereas Jack’s only verb to resolve conflict is “kill,” Delta is occasionally given the opportunity to show restraint–if he feels it’s warranted. When faced with Grace Holloway, Delta is allowed to choose if she lives or dies. While this choice is hamfisted and has questionable necessity–as it’s really apparent that Grace is a victim of Lamb and Rapture as a whole too–it allows the player to decide what kind of man Delta will be: one who seeks vengeance blindly, or one who can take stock of a situation and adjust as needed. This trend continues with other antagonists later on, and the importance of these choices isn’t flattened out by absolutist notions of morality. Killing is not inherently bad in Bioshock 2. Rather, the game acknowledges that there is absolutely a difference between killing Grace Holloway, whose hatred for Delta is largely due to her being lied to and manipulated, and killing Stanley, who pretty much brought everyone together into this web of suffering though his greed and lust for power. Grace’s death will count as a kill towards the bad ending, whereas Stanley’s death has no impact.

Now, an area where Jack and Delta share some agency is the Little Sisters: both are left to decide if they wish to sacrifice the girls for increased Adam, or rescue them and hope that Tenenbaum is good to her word. Adam is once again a precious resource, especially when going up against the far more deadly Big Sisters. But while Jack’s choice only determines which ending cutscene you get, Delta’s influences how Eleanor approaches the world, and ultimately the fate of her mother Sophia Lamb. Though Lamb is the one who wants to impart a grand philosophy into Eleanor’s very being, it is Delta who makes his mark on who Eleanor will become.

While Delta is ultimately still a vessel for the player’s will, once a decision of who he is has been made, that’s who he becomes and other characters respond in kind. Eleanor’s overall outlook on life changes depending on how Delta treats others, particularly the Little Sisters, though the antagonists factor in as well. Because Delta is the only parental figure she has deemed worth emulating, Eleanor takes his actions towards others to heart and frames her mindset based on that going forward. If you save all the Little Sisters and don’t kill Grace, Eleanor will decide that you have embraced forgiveness and so should she. In this instance, She’ll spare Sophia Lamb’s life. If you have more of a mixed playthrough, Eleanor will realize that it’s up to her to decide what she thinks is right in any given situation. And if Delta harvests the Little Sisters and kills Grace, she learns that brutality and serving one’s own interests comes first.

While having the choice to kill Grace is questionable, it does serve as a breaking point for her. Lamb had Grace convinced that Delta was a monster incapable of thought, let alone compassion. By choosing to walk away and leave her in one piece, Delta proves that isn’t the case. When faced with this revelation, Grace realizes that something doesn’t add up and seeks answers from Lamb. If you choose to be a Delta that can acknowledge someone else’s situation and read the room, Grace is given the opportunity to make a change for herself.

Though he never speaks, and we never see his face or learn his pre-Rapture name, Delta is a character in his own right because he has agency and is able to shape the world around him through his actions. He can show empathy, forgiveness, and what’s more, he can distinguish a false equivalency when it’s presented to him–something far more notable Bioshock protagonist Booker Dewitt can’t claim. By showing how we touch each other’s lives, Bioshock 2 makes Delta its most human main character.