Killing Our Gods: A Wound at the Heart of the World: On Lucah: Born of a Dream

Killing Our Gods is a monthly column from Grace Benfell about Christianity, religion, and role-playing through a queer, Marxist, and lapsed Mormon lens.

CW: suicide, death, self harm

Once, when I was a missionary, my coworker and I chatted about salvation. He asked me if I thought I would be saved. I said yes. He replied, “well aren’t you afraid you are going to make a mistake.” “Well,” I said “it’s not so much about whether I will mess up or not, but whether I believe Jesus will redeem me. It’s not about my strength. It’s about his.”

I am no longer so confident.

Lucah: Born of a Dream is about that dread, that surety that if salvation exists it is not for you. Every death ticks you closer to damnation or real non-existence. The only way out, it seems, is to play better, to win more, to master yourself, to overcome your human frailty. Which is, of course, an impossible task. You need a grace that is not available to you. Playing Lucah means facing the terror of damnation. With every death you draw closer to oblivion. It is a potent journey of queerness through patriarchal, heteronormative christianity.

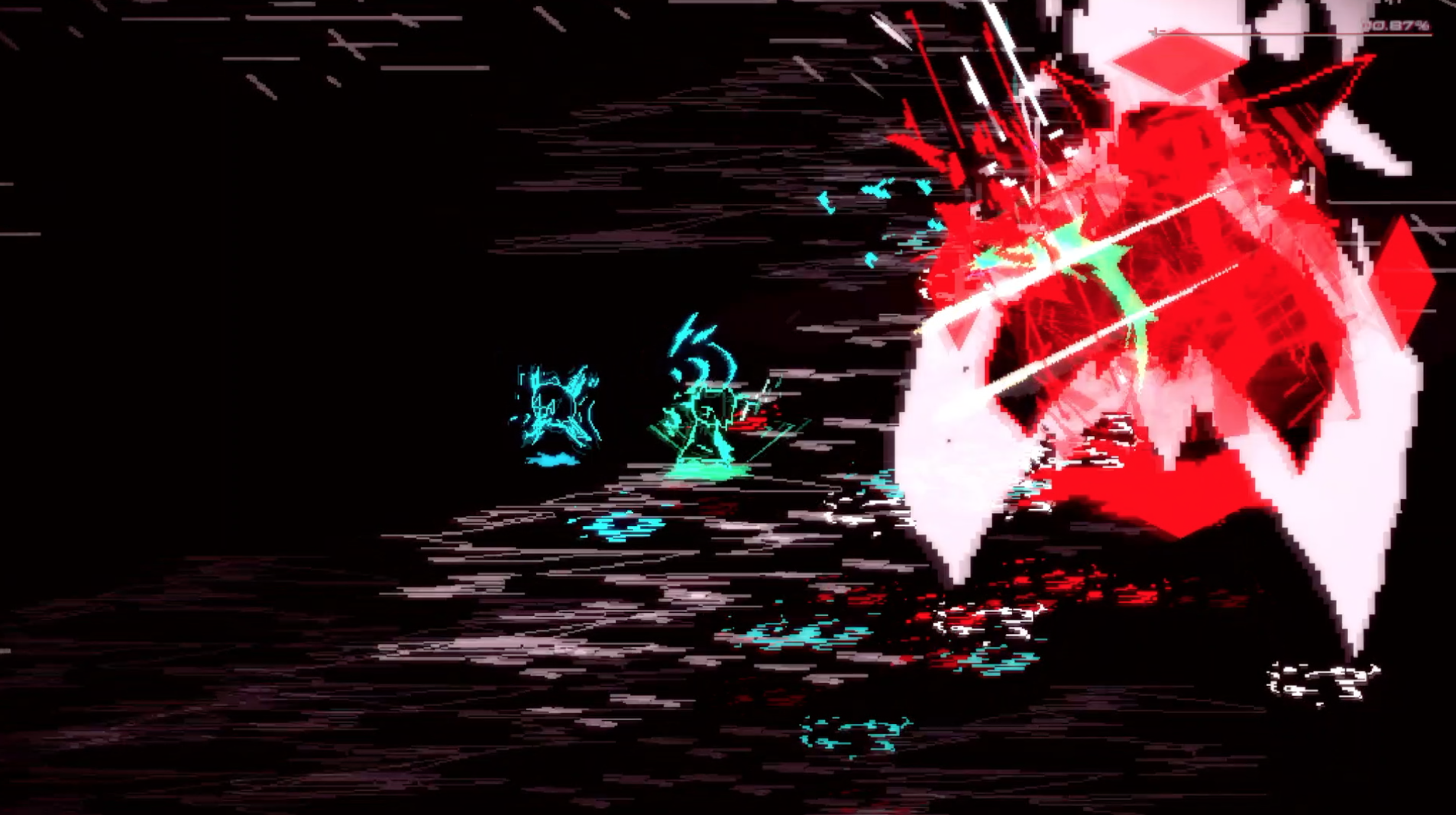

I’ve written about queer youth in church before, on this column, but where Birth by Sleep aligns into resonance with a lucky constellation of haphazard metaphors, Lucah fills itself with the dread of living under the sword of divine heteronormativity. You play as a player-named drifter. The world is a post-apocalyptic dreamscape of abandoned train stations and dead campsites. You wander through to a distant radio tower, with the promise of redemption, or a way out, or maybe just something else. Outside of the occasional town or gathering place, the world is populated by nightmares, ghosts of trauma and hurt that only lash out against those still holding on to hope. Your only real weapon is your will, which spreads out from you in sharp color, cutting through the darkness.

With every stroke, every encounter survived, and especially every time you die, adds percentage points to a “corruption meter.” When it reaches 100 percent, the game hits its lone “bad end.” The drifter has fallen into the nightmares. This creates the feeling of existing in a world where you are not supposed to be. Even surviving ticks up the clock that will mark your dissolution into the void. The stakes of the game are the vague, distant hope provided by the radio tower, contrasted with the all encompassing death and despair.

While the particulars of the game’s narrative are, sometimes frustratingly, obtuse, the emotive tenor is a razor. This is the same promise made to many queer people. A distant oasis, where the problem of queerness is solved, will only exist after death. While the promises of marriage, family, and a life in service are there for every other good christian, queer people must live alone, with peers who likely cannot understand what they feel. It is a life that is impossible to live. While some survive, many do not. Suicide is an epidemic among queer youth.

Christian, your friend/enemy throughout the game, is the most explicit voice of ideation. In your very first conversation with him, he shouts “we don’t belong in this world! Neither of us deserve to live!!!” Even in doing so he claims hold to a redemption stolen from him. “I couldn’t keep hiding,” he says “but Father was so kind and patient… he forgave me for my sin. He said I was almost ready to ascend.” Christian holds to the fundamental contradiction of queerness in heteronormative christianity: while they recognize the pain conformity brings, they also cannot imagine a life outside of it. They are trapped in a system that can only recognize their pain and cannot give them anything but distant joy.

Fittingly, christian symbols gain both menace and comfort. Safe places to stay, where you can level up, are marked with crosses. The kind of crucifix you might see laid down on a bedside table or in the hand of the faithful. Mantras channel your will, give them the sharp form to fight the nightmares. Psychic communications of wounds from beyond yourself symbolize themselves in upside down crosses. Prayer beads grants your drifter more stamina or lets them weather death dealing blows or so much else. For every priest or cardinal who cloaks themselves in violence, there is a symbol that represents your ability to survive. It is a world where the very things that are oppressive help us move through it. This is where Lucah’s programmatic, video gamey-ness feelsmost powerful. Lucah only very rarely gives you verbs that aren’t violent. Existence in a world this dark and is confined means playing by its rules.

~ending spoilers~

Of course, then the only way out is to break them. Lucah only lets you face the heart of the world after beating it twice, as the difficulty continues to spike and as corruption grows harder and harder to manage. The heart of the world is Naomi, a queer person made in the symbol of christian piety. When Naomi and her lover Anna tried to escape their oppressive school, Anna died, and that trauma led Naomi, newly Maria, to cut this world from her wings. But her utopia, meant to free her from the pain of her past life, grows to reflect it instead. The cultish forces that trapped her find their way back in. Queer people die and struggle for life. While Naomi tries to stop it, she is essentially the world’s arbiter. She has recreated the things that destroyed her.

I see in myself, and in my queer peers, much of the logic that once imprisoned us in mormonism. I see it in peers who, leaving a repressive sexual culture, condemn sex work. I see it in the way they talk about masculinity as a set of definitive traits, immutable and all powerful.I see it in myself as I shadow myself with guilt for not being the son my family might have wanted, or condemning too quickly, too harshly. Queer liberation cannot be made by recreating puritanical, punishing moral logic with a rainbow flag. The way out then, is to imagine oneself as one is. When Maria becomes Naomi again, she recognizes this. In that recognition, the world is destroyed, freeing those trapped inside it. In the final ending, Christian turns toward the drifter and says “we’re not what they told us we were. We’re not who they want us to be. We’re us.” We cannot transcend our trauma, but we can acknowledge it, live with it, breath in it and out, be ourselves. After all this bleakness, maybe that’s enough.

~conclusion of ending spoilers~

In that spirit, I want to wrap this up with the promise of redemption, with the promise of a body made new, a body of our own. In some ways, Lucah’s final ending would let me do that. But so many of us are fucking dead. For each of us who, by some miracle, get free, there are so many of us that die. None of us emerge unscathed. Even in our escape we cannot totally forget the rules that made us. It is a lifelong battle to rewrite them.

However, maybe that’s the point. Our trauma ripples out, the world marks it. It remembers. I am not being hyperbolic when I say that the world under patriarchy, under imperialism, under heteronormativity, under oppression is haunted. There is both dread and comfort there. We are not alone and dead things do live on, but they will never be the same. Nightmares, dreams, and spirits alike remain. Still, I think of the ghosts yet to be, for now only haunted by themselves. How many inner worlds are dead or dying, with rainbow spirits drifting through, surviving with only their will?

Too many.

1 thought on “Killing Our Gods: A Wound at the Heart of the World: On Lucah: Born of a Dream”