Screenshot provided by author

The Dreadful Weight of Feeling Seen in Nier Replicant ver. 1.22

Spoiler Warnings: Nier Replicant ver. 1.22…, Nier: Automata

Content Warnings: Suicide and suicidal ideation, gender and body dysphoria, use of reclaimed homophobic slur.

Feeling seen has weight. Drakengard and its Cult of the Watchers know it. Nier: Automata and its blindfolded YoRHa units know it too. Of anyone in the Drakengard and Nier franchises, Emil knows it most of all. Feeling seen is your body hardening to stone. Feeling seen is begging loved ones not to look at your monstrous form. Feeling seen is thanking a friend for recognizing you despite everything. Playing Nier (be it Gestalt, Replicant, or Replicant ver. 1.22…) makes me consider how much I want to feel seen. Watching Emil discover his found family and–subtly–express his queerness makes me feel seen because my experience is being represented. Hearing him choke out sobs born of self-perception reminds me why the phrase goes: I feel eyes on me. I feel perception squeeze my body through expectations of weight and gender. Perception is a harrowing thing to endure. For Emil and I, that feeling is rooted in an antagonistic relationship to our bodies.

The player meets Emil before his fusion with his sister. For hundreds of years, trapped unchanging in the body of a young boy, he did not need to reach out a hand to touch someone. Whomever his gaze fell upon would feel the effects of that look physically as their body turned to stone and–in most cases–their life ended. From a young age, he felt cursed by his body; an antagonist that would go on to vex him for centuries. Meeting the protagonist, Grimoire Weiss, and Kainé brings Emil out of isolation and into a found family who see him not as a monster, but a friend. Kainé especially, marginalized for years for her intersex body, begins to orient Emil away from feeling shame for his body and towards the endless journey of embracing it.

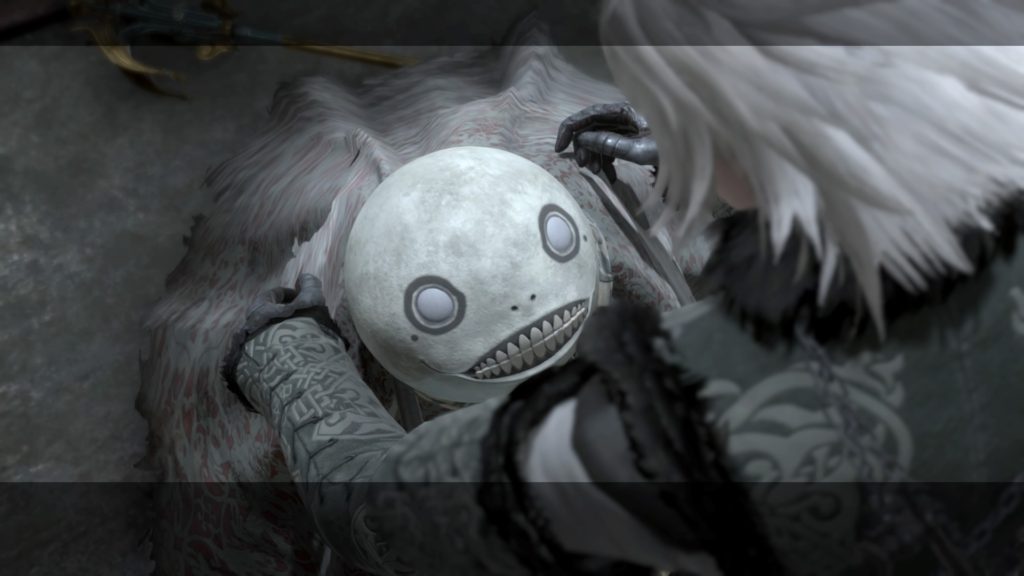

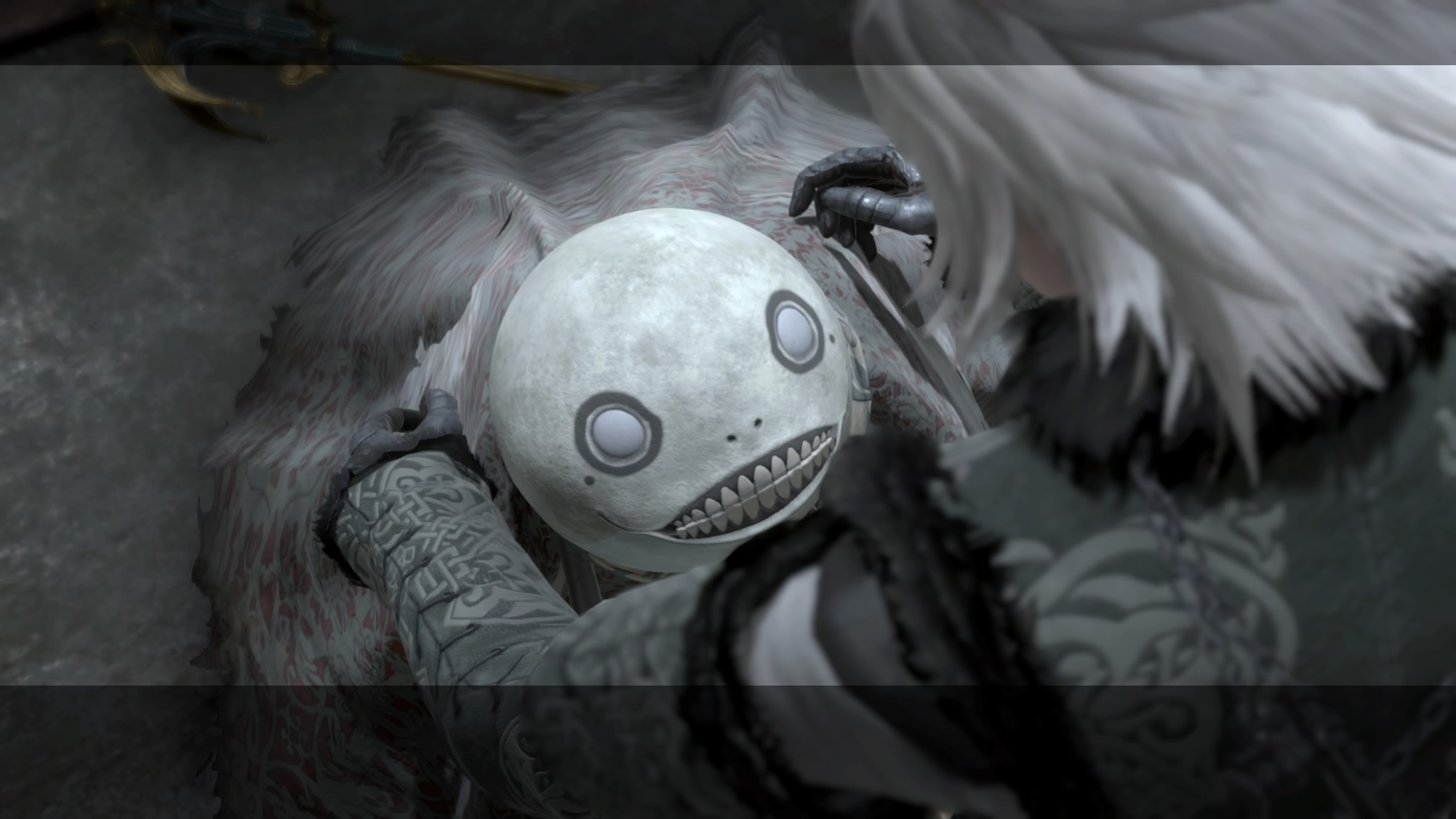

Alas, irony only compounds his misery in Replicant’s second act. While fusing with his sister’s body restores his ability to cast his gaze on other people without petrifying them into statues, his new body—skeletal from neck to toe and crowned with a rictus like a ghoulish man in the moon—inspires a new fear within him of other people casting their gaze on him. He no longer fears seeing, but being seen. It’s the same reversal which occurs as one leaves closeted life to live openly in their queerness.

While closeted, I feared my longing gaze at other boys would manifest in physical harm to myself if that gaze was noticed and interrogated. Outside the closet, the source of that fear shifted from my gaze to others’. I feared how straight people’s perception of me as an out queer person might manifest in physically felt pain. Under queer people’s gaze, I feared being measured against the standards of queer bodies I’d seen on TV, and being found lacking.

Those “representations” of queer people exacerbated the hatred I hold for my fatness as well. One of many examples: Will & Grace may have shown me gay characters living full lives (even if many of them were played by straight actors), but over a decade later, the sound of Jack’s singsong “Pecs get sex!” rings in my ears like Louise’s obliterating wail. I long for Emil’s billowing layers of fabric which hide his skeletal frame. Unceasingly, I tug down at my shirt, for even an imagined gaze is made physical in my anxious attempt to hide as much of my body as I can. Our hatred for our bodies creates pressure in both myself and Emil to overcompensate for that supposed deficit in value. In a piece on Nier’s portrayal of queer bodies, Austin Jones succinctly encapsulated this dynamic:

“Queer people are often told that their bodies are unworthy, ugly, or loathsome unless they are somehow useful…are they entertaining? Do they ascribe to popular beauty standards? Do they have some kind of talent that contrasts their otherwise repulsive selves? A queer person fitting into mainstream society is possible, but requires a level of submission and assimilation.”

Emil feels he must make himself useful, and therefore valuable, by acquiring power and mastering magic. I do the same by being the funny, fat friend. In my younger, even more insecure years, the sassy, funny fat friend; the kind that will go shopping with you and make their queerness the butt of the joke as long as it meant their straight friends were laughing with them and not at them.

The further from heteronormativity one leans, the further such “submission and assimilation” drift out of reach. Emil’s body not only frames him as monstrous, but presents a complicated gender dynamic; one which also makes me feel seen in the sense of representation and feel seen in the dreadful way I’ve described while existing in the world as not only gay, but trans nonbinary.

When Yoko Taro says Emil is simply gay, I agree. When his and his sister’s bodies fuse, that act does not instill “feminine feelings” in him which lead to his attraction to the protagonist. Attraction to men is not an essentially feminine trait. However, that fusion cannot be written off as irrelevant to his existence within the spectrum of gender. To be clear, Emil’s transformation is not analogous to transition in the real world. Though he chooses to fuse with his sister’s body–itself already engineered to be monstrous and deadly–that choice results in painful, dysphoric consequences. Transition is meant to be a freeing, actualizing process and that is not what Nier presents. In addition, this is not an essentialist bringing together of male and female to fulfill some binary lack of the imaginary phallus. Rather, through transformation, Emil is placed beyond the cisnormative binary where he must deeply consider his body and his identity within it. He trans-figures.

While this trans-figuration may not be analogous to real world transition, it positions him at an intersection in which I feel seen. Realizing I am trans served as a first step on a journey towards gender euphoria, but stepping out of a binary and onto a spectrum overwhelms as much as it liberates. I no longer need to conform to an expected presentation, but I also have no standard with which to measure myself besides my own desires.

When you’ve lived a couple decades never considering how you want to look, the sudden access to possibility (barring finances and fatphobic clothing sizes) can be almost too much to process. I know how Emil feels when he is overwhelmed by the freedom his trans-figuration affords him. He can move through space uninhibited by gravity and access new verbs with the powers granted by his sister’s body. Nevertheless, such power doesn’t spare him the feeling of being overwhelmed into helplessness when he loses control of the very body which sets him free.

When Emil is at his lowest, his found family raises him up. Nights by the campfire with Kainé, embraced and reaffirmed by the protagonist when he needs it most; the time he spends with his loved ones validates his queer existence and even begets “pride.” However, in the same moment he declares his pride, he decides to forfeit his life. He has access to pride, but it exists alongside, not in place of, the hatred he feels for his body. Though he sacrifices himself to save his found family, I feel seen in how calmly Emil determines he can be disposed of. My suicidal ideation, even if born from a place of hopelessness, is always rational. Calculated. It never manifests as an eruption, but instead as the result of weighing wins, losses, possibility, or lack thereof. It feels as simple as deciding that despite the seemingly infinite power at his fingertips, Emil chooses not to wield that power to save everyone, but instead, to separate himself from his friends and gently nudge them forward to safety, while he drifts back to face oblivion alone.

But Emil and I live on. Though the possibility our queerness affords us is endless, we’ve met with a cliff edge of our existence, and in doing so, learn we can come back from it. In her introduction to the 2019 edition of The Faggots and Their Friends Between Revolutions, filmmaker and activist Tourmaline writes:

“The faggots remind us that to become undone is our greatest gift to ourselves. It is truly our greatest path to being response-able – to feel our feelings authentically makes us able to respond to the conditions around us with an open heart.”

Before the magical barrier separating his body from Poppola’s lethal magic collapses, Emil curls up at the edge of existence and feels his truest feeling: his love for his found family. His body is destroyed, he has “become undone,” and in doing so he is able to channel that raw, ceaseless love for his friends and hurry towards reunion; both with his monstrous, liberating body and with his family. He even further queers his body with a few extra arms; trans-figuring once more to extend the scope of his reach and grasp his infinite potential.

At last, I do not feel seen. Emil’s determination and trans-figuration after his return from the brink do not represent my experience. I feel better seen in Nier: Automata’s Pod 042 who, when reflecting on their failed attempt at taking their life, states plainly: “I must look very silly.” I understand, Pod 042. Feeling seen as silly is embarrassing and as Pod 153 replies, “being alive is pretty much a constant stream of embarrassment.”

As I stumble around in the intersections of dysphoria which make me dread feeling seen, squinting my eyes as my authentic self flickers in and out of focus, I look to Emil to remember. Our bodies may trans-figure, we may come undone, but pride can exist alongside dysphoria. The love of our friends can wrap around us even as we curse our perceived monstrousness and despair. Through queerness there is possibility; wherein I can lean into the aspects of myself which differentiate me from the cishetero norm, safe in the knowledge my found family will not let me fall. Like Emil, I must be unafraid to trans-figure my body and mind, knowing they will be seen, and extend the scope of my reach.

1 thought on “The Dreadful Weight of Feeling Seen in Nier Replicant ver. 1.22”