Image Source: Analgesic Productions

Sephonie: Diving Into the Body of the Earth

Sephonie opens on a train that carries an island. The titular island, Sephonie itself personified, rides to an as yet unknown destination. Though blunt and obvious, this opening blurs several lines. Sephonie is a non-human thing doing something distinctly human, putting its arm over a chair, talking idly as the train rattles through the landscape. It is and is not an individual, is and is not artificial, just like every living thing.

Sephonie is about these contradictions, particularly the arbitrary lines we draw between technology and nature, or human beings and the natural world. Often we discuss the need for “harmony” with nature or the responsibility of stewardship over plants and animals or a reciprocal exchange between humans and flora/fauna, but all these descriptions sharpen borders between humans and everything else. Every human being relies on food and sunshine; could it not be said that the earth cares for us? We would not understand a microbe as part of our selfhood, but yet, what would it be without our body? What would we be without all the things that make us up?

Consider, for example, the way we talk about any kind of assistive technology. A wheelchair or pair of glasses might become part of our bodies. Nurturing plant life requires technology like plumbing or even just stakes and ties. Relying on tech-utopian solutions to climate change is a surefire route to disaster and further environmental exploitation. But technology, of varying levels of complexity, will play a role in healing and understanding both ourselves and the world. Sephonie offers a solidarity between the “man-made” and the “natural” that is a fact of life, one we can either choose to ignore or accept.

Sephonie cuts to the bone of these issues through science fiction abstraction. The game follows three scientists: Amy, a Taiwanese-American woman from Blooming; Riyou, a Japanese-Taiwanese man living in Tokyo; and Ing-Wen, a Taiwanese woman dwelling in Taipei. The trio are part of an international cooperative group, set to explore the unique ecosystem of Sephonie. All three have been implanted with an experimental technology, ONYX, which both gives them the game’s platforming powers and allows them to mentally interface with Sephonie’s unique flora and fauna. As soon as they land on the island, a mysterious shield appears and blocks them from leaving. Dedicated to their work, and with nothing else to do, the trio begins to explore. As the trio moves deeper into the island, it begins to shift around them, at first replicating an office all three visited back in the United States, then recreating entire sections of their hometowns. The technology implanted in the trio that enables them to analyze and explore the island creates a psychic connection to the island itself.

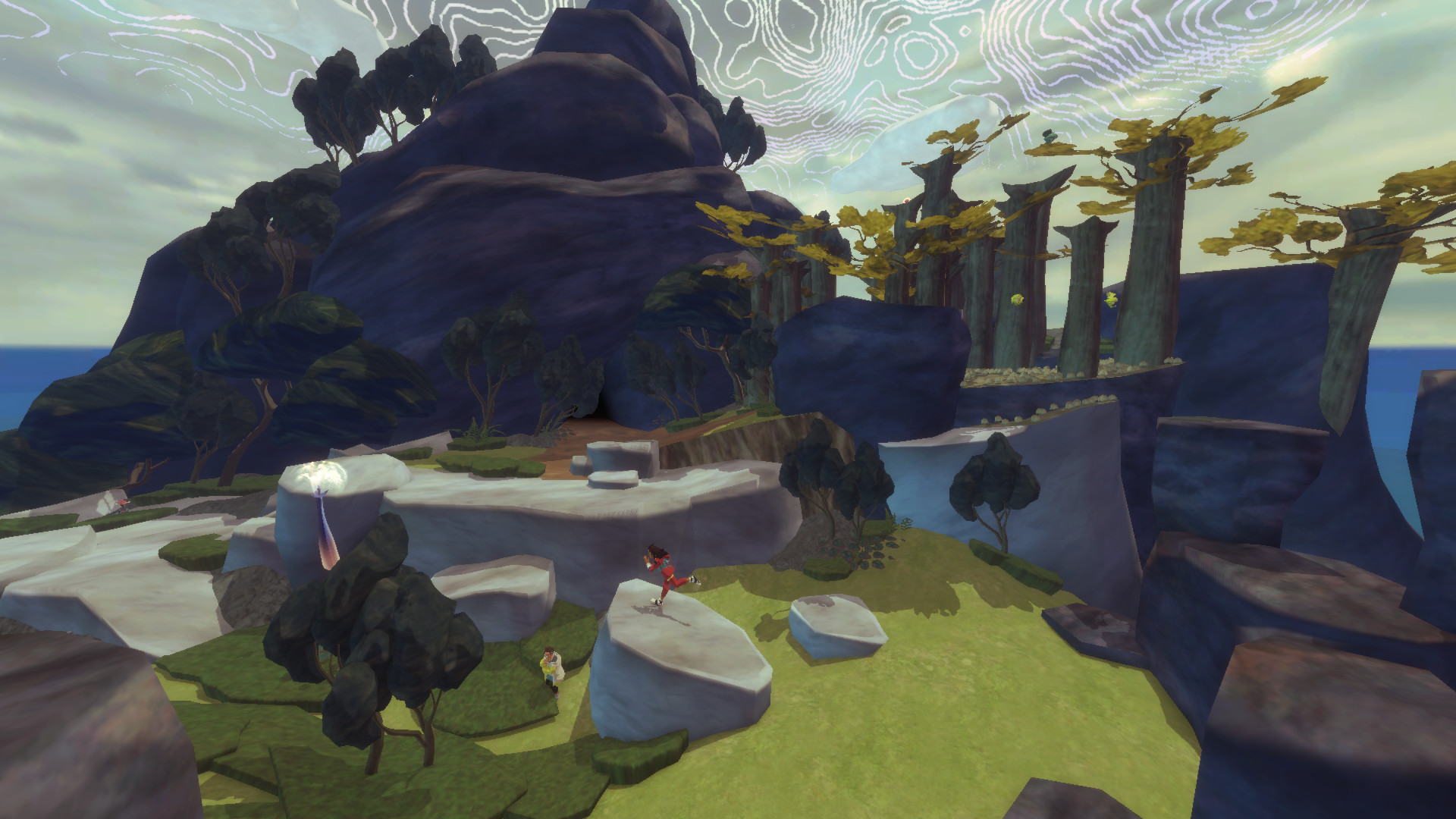

I wrote in my review about how Sephonie turns the language of 3D platformers contemplative. Platfomers, by definition, rely on the player learning and understanding the rules of the world. This usually results in the kind of expertise it takes to finish an obstacle course. In contrast, Sephonie takes such interest and care in depicting ecosystems that the island feels more like a world than a training regimen. Sephonie’s levels are not entirely nonsensical, though they do have their share of contrivances. All of them put together create something that resembles a holistic landscape.

But the platforming is just part of what makes Sephonie’s ecosystem tick. To examine and study flora and fauna, players will play a puzzle game of placing tetrominoes, with obstacles and quirks based on the creature’s environment or traits. The relationship is not antagonistic, though. The obstacles are not attacks, but conditions, the things that must be understood in order to understand the object. The tetrominoes are also objects at the heart of video games iconography and popularity. They have an association with sheer, cold computing, seemingly as far as one can possibly get from the messy realm of the natural. Here, they become a means of the universe understanding itself.

Crucially, the trio’s exploration and study of the island does not mark territory or land, nor do the trio extract any materials – though many of the trio do consider what could happen to the island after their project is over. Most of the game’s collectibles are items the trio brought to Sephonie. All of Sephonie’s verbs are related to exploring or understanding. The ways the island recreates the trio’s hometowns does not disrupt the existing ecosystem. All of Sephonie’s parts, plants, and creatures are found living within and around these new structures. This is partly because, of course, Sephonie is not real. Constructing buildings requires that some harm be done or things be changed, just as a beaver requires wood for a dam. Sephonie’s construction is metaphorical more than literal.

However, this is also because Sephonie is now different, but it has not been harmed. So much of how we understand environmentalism, especially in ecofascist strains, minimizes humanity: There should be less people and they should act less. Obviously, any serious response to climate change requires an immense reduction in power usage and a massive restructuring of supply chains. But it also requires a more direct relationship with the natural world, more activity, not less, with the right methods of cultivation and a centering of indigenous peoples and their expertise. Sephonie is not a treatise on how exactly climate change should be combated. The trio change Sephonie, not because of a comprehensive cultivation program, but because they are there. However, Sephonie does make an argument in centering people as part of its environmental story. It reframes their own personal struggles with identity as a “natural” struggle, something that nature itself can reform. The plurality of protagonists, all with interlocking but distinct cultural backgrounds, plays into Sephonie’s sense of a global ecosystem.

To be clear, Sephonie is not merely a psychic repository for the protagonists. It has a will of its own, both personified and inhuman. After the trio make their way deep into the island’s caves, Sephonie takes the form we see at the beginning of the game, proclaiming its intentions to guide the trio. With their help, Sephonie can cure the null virus, a deadly disease festering at the island’s heart, which will eventually break free into the wider world. This moment of revelation is treated almost as the divine revealing itself, the contact between the indescribable and the logical world. Sephonie’s selfhood existed before the trio ever came to the island. However, its clarity and singular humanoid shape are a direct result of the trio’s presence. It is a moment of mutual care. As the island grows to resemble the humans, they also grow to resemble it.

In a further blurring of lines, the connection between Sephonie and the trio is erotic, if not exactly sexual. Riyou is not being unfaithful to his husband, for example. But as the trio and Sephonie grow closer, the boundaries between their selves begin to blur. The game introduces monument-like images of their bodies. They grasp at each other, lips almost touching, hovering around Sephonie, a unity of every kind. Even blood and come are creations of the earth. There is not a lot of predation in Sephonie, at least towards its human characters, but these moments of near unity are the closest the game gets to horror. The blurring of selves can come with discomfort, and in the case of the virus itself, it means staring into the heart of extinction. All the tension between life and death hangs in the gasp before orgasm.

The game ends in a kind of denial. Just as the trio reach the center of the island, and nearly bond with Sephonie to destroy the virus, the rescue crew arrives. They smash through the island’s barrier, severing the connection, and take the trio back. Once the trio returns to the normal world, they begin to forget the things they learned about themselves and each other. The trio’s friendship vanishes, with them keeping only a little contact over the ensuing decades. The game’s epilogue introduces a new character, Gael, who returns to the mystery of Sephonie after the Null Virus has already broken loose. Eventually, they gain contact with the island and rebuild the fraying connection between the trio and Sephonie. Because the data from the scientists’ trip has been saved, Gael can help reconstruct a cure for the virus.

Fittingly, Sephonie takes a long view of things. Seeing the threat of the null virus and the struggle of the trio as part of an ancient, ecological time. While Sephonie centers humans as part of an ongoing ecological crisis, and part of the potential way forward, it also reprimands individualistic hubris. We cannot fix everything on our own, or even in the present, but with the chain of hand on hand, with collaboration between generations, with an understanding of nature that goes between simple divisions, much can be healed.

It’s difficult to overstate how complex Sephonie is, both the entity and the game. As sprawling and ambitious as this letter is, it does not even approach the game’s truly dazzlingly layered character work or the way it dances between formal moves like “single take” cutscenes and walls of text. These things deserve, and have gotten, deeper critical study. Still, all those things do serve to blur the boundaries that we struggle the world around, and the violence those boundaries are enforced with. Sephonie explores the ways that nature is a part of us beyond the binaries of utility and the untouched wilderness. It considers how we might build a relationship with nature, and thereby ourselves, friendly, erotic, lovely, exhausting, terrifying, and necessary. It believes that the technology that changes our bodies could move us closer to the land, if we use it with care and consideration. What would we and the earth remember about each other if we had our hands in the dirt?

If you like what we do here at Uppercut, consider supporting us on Patreon. Supporters at the $5+ tiers get access to written content early.

3 thoughts on “Sephonie: Diving Into the Body of the Earth”