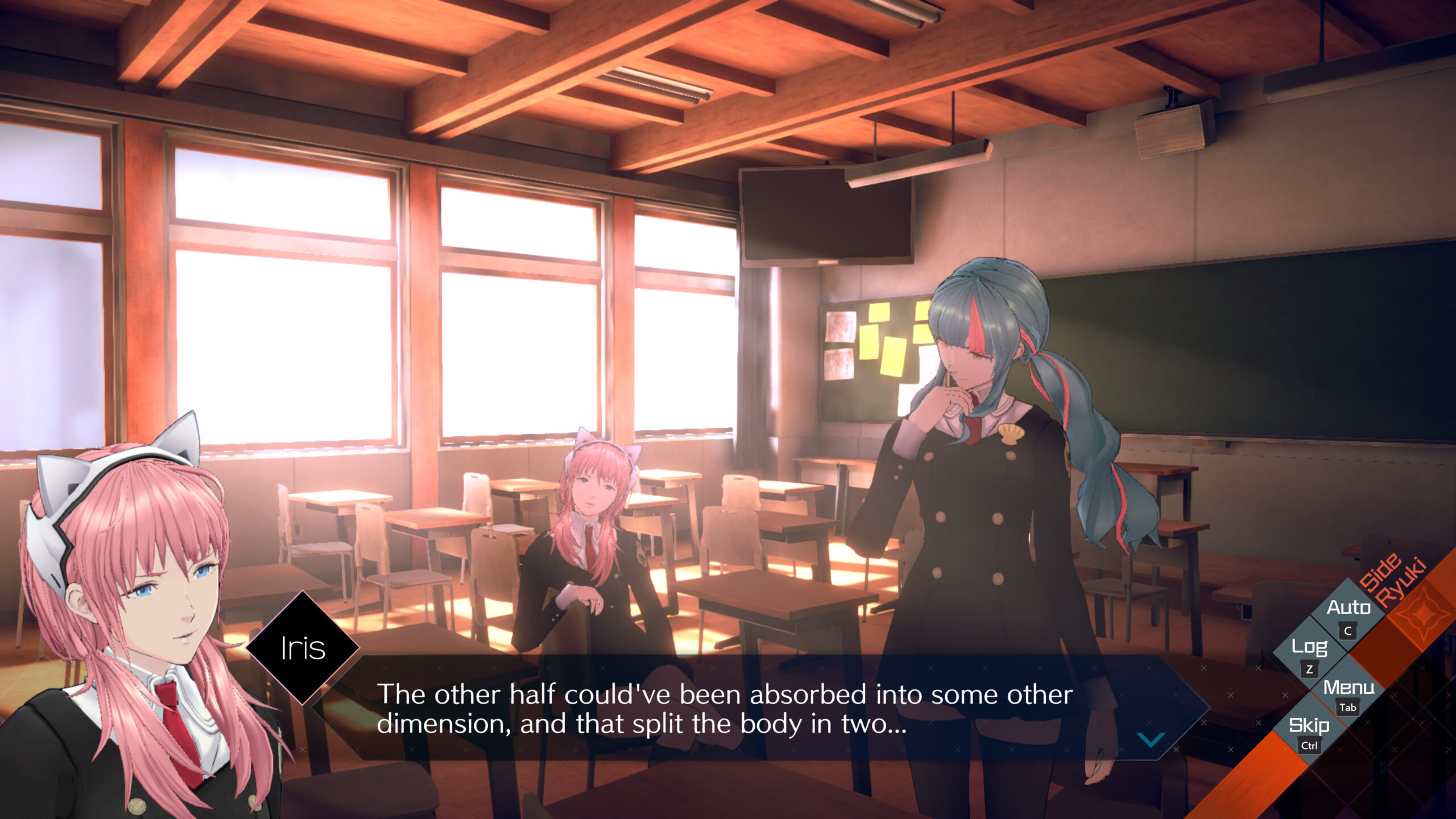

Image Source: Spike Chunsoft

AI: The Somnium Files Nirvana Initiative: A Conversation About Duology

AI: The Somnium Files (officially a.k.a. AI1), is a cult favorite mystery adventure game series from Spike Chunsoft that launched in 2019. Directed and written by Uchikoshi Kotaro, a veteran writer of acclaimed adventure games and visual novels like Ever17 and his Zero Escape series, a brief synopsis for AI as a series is thus: in the near-future of Japan there exists a specialized detective unit codenamed ‘ABIS (Advanced Brain Investigation Squad).’ This unit uses advanced tech, namely AI-balls (essentially AI partners contained within a synthetic eye-ball) and the PSYNC (Photo Synaptic Neuro-Coupling) machine to analyze crime suspects’ dreams by turning them into physical landscapes to explore and investigate. The first game had the core theme of exploring ‘many different aspects of love’ according to Uchikoshi, with a murder case that involved an elusive eye-gouging culprit known as the Cyclops Killer. It was a game that was very aware of its themes, expressing them in ways both comedic and philosophical across its many intersecting story routes and timelines.

An excellent and obvious example of this special self-awareness can be found in the title itself. The deliberate wordplay of AI (which can denote protagonist Kaname Date’s artificial intelligence partner, be pronounced like the word ‘eye’ and the Japanese word ‘Ai’ or 愛,meaning ‘love’) and somnium, which is latin for ‘dream,’ spell out one of the central themes in plain sight. While AI1 wasn’t a wild success, it garnered enough of a following with its smart writing and innovative Psync mechanic that it garnered a 2022 sequel—AI: The Somnium Files – nirvanA Initiative (AINI).

If AI1 was about love in its many forms and how technology mediates or obstructs it, AINI is arguably about our thresholds for empathy, and goes much deeper with its narrative design. Uchikoshi (who wrote but did not direct the sequel) has been quoted explaining the core themes of the sequel being “‘two is one’ and ‘two opposites’” and as with the first game, the mystery case reflects these themes as well. Mizuki, Date’s adopted daughter, has become an ABIS agent and is investigating the Half Body serial killings with Aiba (Date’s estranged AI-ball), where victims are sliced in half at the molecular level by the culprit Tearer. But she isn’t the only one on the case. Ryuki, a traumatized yet brilliant new ABIS recruit, has been paired with newly developed AI-ball Tama who functions both as his partner and therapist. The game switches between these two new detectives’ perspectives.

Since there’s such an emphasis on duality in AINI, we thought it would be best to approach this letter in the style of a conversation.

Phoenix: One of the things I love most about AINI is how it portrays a nuanced near-future world. Like our current world state, the Japan of AINI is a place where technology isn’t taken for granted even though it’s ubiquitous. Everyone in AINI’s world is becoming more aware of all their various relationships to tech and social media, how it mediates even our “offline” relationships to people and the world.

Mina: The way it’s presented is quite fascinating, honestly! I’m a sucker for sci-fi futures which feel like they could be just years away, and both AI games pull it off so well. What I’m most interested in, though, is the way this future technology affects the way the cast builds relationships with each other, and how the player’s perspective is affected by the information presented via technology. AINI is a game determined to explore the concept of empathy, and to that end utilizes a few crafty narrative tricks (mostly through the lens of the aforementioned tech) to help the player understand and empathize with practically every character in the cast, their personal crimes or histories be damned.

Phoenix: Agreed! I find the AI series fascinating as well for how it leans into the concept of empathy and that contentious term “empathy machines.” I believe Uchikoshi is very aware of how game designers can go awry with assuming that games generate empathy. There’s been a lot of talk over the years about how empathy isn’t something you acquire or “level up” from external sources like art or games, which are sometimes artful in their design. Samantha Greer recently released a video essay about how games are more like mirrors, which can show us whether we bring our personal empathies for the characters involved in the game’s text or if we don’t. That Uchikoshi involves the player in the text of AINI and its mechanics makes me feel like he wants the player to question their relationship to games as a text. Especially since so many players engage with games in an escapist fashion, or to embody a power fantasy in some capacity. Which narrative tricks do you feel were most effective or affective in AINI?

Mina: In particular, I appreciate the way that Psyncs (both as a function of the gameplay and the narrative) are utilized in AINI versus its predecessor. One of my main criticisms of AI1 was that the Somniums often felt like they interrupted the narrative rather than serving it. Mechanically, they were puzzle rooms dropped into the game to break up the more visual-novel-esque investigation segments. Though they were presented as being a way to gain new insight into the Psync subject and thus more leads in the case, it was in actuality very uncommon that we really learned anything new or interesting about the subject during the Psync. Part of this is owed to the amount of overlap in Psync subjects that AI1 had (given that two characters are Psynced with twice and one particular subject gets THREE Somniums), but it also just felt like Uchikoshi didn’t quite understand how to make that marriage of gameplay and narrative fit quite yet.

AINI, by comparison, uses the concept of Psyncing incredibly well. Every Somnium is used to either introduce a character or deepen them, and there’s a particular focus on each Psync subject’s motivations, desires, hopes, and dreams. You get a much better feel for each character via these segments, and it wound up endearing me even to figures I thought I would despise. Without getting into spoilers, I think the game’s final, climactic Somnium does an excellent job of showcasing the killer’s motives without necessarily justifying them. It leaves it up to the player to decide whether or not they were ‘right’ to do what they did, and that ties into your earlier point about games not being able to create empathy. All AINI can do is give you all the pieces to the puzzle and let you decide how pretty the picture is, and I think that’s smart writing. It reminds me of how last year’s Psychonauts 2 similarly-handled the subject of empathy via dreamwalking – sometimes, the best way to explain a character isn’t to have them explain, but to depict how the universe of the fiction has affected them. It’s a sort of ‘show, don’t tell’ approach that works wonderfully.

Phoenix: Yes! Often I think we, as players, overlook how game narrative mechanics like Psyncing need to be revised and developed in the same way that traditional fiction writing techniques or tropes do. Uchikoshi took a big creative risk with Psyncing, as it’s a paradoxical mechanic that must convey a dreamlike space to the player while offering them straightforward actions to perform within it. Thematically he needed Psyncs to feel as surreal as natural dreaming does, but operate in a way that would feel intuitive to his players’ logic. I like that you mention him needing to navigate the “marriage of gameplay and narrative” because he’s essentially marrying the puzzle rooms of his Zero Escape series with a newer, less deductive mechanic heavily relying on environmental storytelling.

Uchikoshi’s last game before the AI series was Zero Time Dilemma – which is often perceived as more visual-novel-esque or even akin to interactive fiction – where everything is mostly driven by choices and revisiting those choices until you reach a “true ending.” I think that definitely shows in his trouble with the Psync mechanic in AI1. Although the criticism of AI1’s somniums is valid, there’s a part of me (probably the arts and humanities part) that loves the formal interruptions of the Psync sequences. In a ludonarrative sense, somniums work best as interludes, since they are dream-like, but they should further or deepen the player’s understanding of the characters, themes and plot. So, as you said, it’s very much a ‘show, don’t tell’ situation. I think the introduction of Wink-Psyncing – which gives you 30-seconds of insight into whoever you’re suspecting – is another one of the ways Uchikoshi has smartly revised this mechanic as well.

AINI also surprised me with characters that I didn’t think I would feel empathy for. Particularly Tokiko, the head of Naixatloz’ Japan branch. When you first meet her she’s almost like a cipher for the organization, parroting Naix’s conspiracy-based philosophy and esoteric beliefs as facts. But her first Psync reveals hidden depths and connections to other characters she’s offered questionable yet concerned guidance to. Then you slowly learn she has a troubled personal history and things start to fall into place. Characters like Tokiko and the killer are challenging and I believe get to the heart of the matter regarding empathy and how technology in AINI’s world facilitates such empathy. And not just for the player, but the rest of the cast too, especially the ABIS agents.

Mina: Tokiko is actually such a fantastic synecdoche for the game at large. The narrative quite specifically refuses to condemn or endorse her actions, meaning it’s up to the player to decide if she’s a deeply-flawed but ultimately sympathetic figure, or if the harm she causes with her ideology and influence outweighs the nobility of her (stated) goals. I have friends who are still arguing about this half a year after completing the game! The fact that characters can be so divisive is a testament to the quality of the narrative structure as well. The order and manner in which you learn information can GREATLY affect your opinion on these characters, and even cause you to completely turn around on them over time.

You mentioned Zero Time Dilemma earlier, and that’s another instance of Uchikoshi honing his craft over time. ZTD employed a weird (and oft-derided) structure wherein the order in which you experienced the events of the game were semi-random. The player was fed plot “fragments” piecemeal and only upon completing these vignettes (usually consisting of a puzzle room with wraparound narrative cutscenes) was one allowed to see where and when these events were situated on the game’s sprawling timeline flowchart. This absolutely affected the flow of the game’s plot and could in some cases even cause twists to be revealed INCREDIBLY early on, which would then paint your opinion on characters and events for the rest of the game. AINI kind of goes in the opposite direction, adopting perhaps the most linear plot progression and flowchart of any of Uchikoshi’s games thus far. But this tightening of the scope was an extremely smart move. It allows AINI to dole out information at precisely the pace it wants, which is critical if you want the player to be invested in the story, and – more importantly, in my opinion – care about the cast.

Take struggling comedian Komeji, for instance. When he’s first introduced, it’s as a pitiable figure: he’s drowning in debt trying to make ends meet, has alienated not only his estranged ex-wife and daughter but his young son as well, and seems to flounder every opportunity at escaping this ever-deepening hole offered to him. It’s very easy to dislike a screwup of this caliber, doubly-so when you find out that his personal failings are putting his loved ones (and potentially the investigation) in jeopardy. Yet, when I reached the scene wherein he proudly reminisces about the day his son was born and how he decided on the boy’s meaningful name, I truly did feel for him. Komeji may be a deeply flawed man, but he never stops trying to do right by those he cares for, and there’s certainly something to be admired there. That was probably one of the more pronounced instances of the game taking a character I had written off as a lowlife and forcing me to reexamine them, and it only works because of how those scenes were ordered. If the game were structured like AI1 or the earlier Zero Escape games with multiple branching timelines you can explore in (almost) any order, I don’t think I would appreciate moments like Komeji’s heart-to-heart nearly as much.

Phoenix: I absolutely agree that AINI tightly controlling what information the player is privy to, is a brilliant move. Parallel to real life, the only thing we truly know about people and the respective worlds they live in is that we don’t know a whole lot. You have to put faith in people, but also negotiate a balance between that and personal boundaries (both physical and mental).

I think, for me, Komeji’s arc is where my empathy hits its limit as a player. While I understand how he’s definitely written and revealed in the same way as the rest of the cast (save Chikara, of course), I felt strongly about what he put his family through. His selfishness was a bit too hard for me to bear, especially when his children were very close to being destitute. Yet I love that Komeji’s not an easy character to sympathize with. He’s willing to do absolutely anything for his family once he realizes how deep their troubles are, as you said. In a way, he tests the player’s empathy in a similar vein to Lien, as a former lockpick expert who’s basically stalking a schoolgirl because she lifted his spirits during a dark time in his personal life. The cast of AINI is chock-full of individuals that are so singular in their goals and backgrounds that you’re forced to evaluate where you stand on any one of them fairly quickly.

Often I found that when I was at odds with a character, like Komeji or Lien, I would look at their relationships to other characters. For Komeji, as you pointed out, the scene recounting Shoma’s naming brings an authentic sense of warmth to a character that makes him more tragic than deplorable. Even if I can’t bring myself to empathize completely with Komeji, I can certainly at least feel a measure of sympathy for his woes and regrets. The duality of comedy and tragedy they explore with this character and his failings within an late techno-capitalist system also points to how such systems are so unforgiving for individuals who aren’t making “the right choices” all the time.

Uchikoshi is very adept at capturing the ways that people at various intersections of society are let down by techno-solutionism, or in the case of Chikara, believe that technological advancements can solve not just infrastructure-related problems but existential ones as well. This concept leads individuals like him to take advantage of others who aren’t as tech-savvy, often in horrible ways, but feel justified in doing so because they see themselves as a savior of sorts (or are simply power-hungry). The world of AINI has definitely come a long way, but even in a world where you can see inside people’s minds, we don’t necessarily see the bigger picture any clearer. Characters like Tokiko, the killer and Chikara (the extremes) push for tech to fix the world or remake it to their standards.

Naixatloz and Tokiko, in particular, believe we are all part of technology and they’re not far off. While we might not be in a simulation a la the old Matrix conspiracy, we are all living in a society that’s interlaced with technological infrastructure (both bleeding edge and mundane). But both Naix and Tokiko fail to see that trying to solve existential crises with tech doesn’t necessarily get at the root of the suffering the characters experience. There’s one chilling ending that challenges Naix’s philosophy even as it confirms certain metanarrative beats about AINI’s world. As well, the world becomes empty or even meaningless when all the characters have their problems erased artificially.

Mina: I do absolutely love the sort of dividing line that Uchikoshi draws between technology and the ideal of ‘utopia.’ Culture keeps advancing, but with these advancements come all-new problems which can be caused by technology just as often as technology is able to fix them. My absolute favourite character in the entire game is The Masked Woman, a mysterious figure who appears sporadically to aid or hinder the investigators in accordance to her own enigmatic whims. The Masked Woman is someone whose life was irrevocably ruined by the irresponsible use of science and tech in the pursuit of ‘utopia,’ and yet she’s only able to live and pursue her goals because of the advantages that certain advancements provide her.

She’s kind of a living contradiction in that regard, but it’s a good snapshot of AINI’s anti-techno-solutionism – the tech which helps and hinders her isn’t inherently good nor evil, but the fact that it can be used to catastrophically impact lives as easily as it can be used to save them illustrates the dangers of relying on tech to magically fix society’s ills. In the end, it’s the meaningful bonds she forges over the course of the game and the ones she had already forged in the past, which end up helping her far more than any gadget could.

That actually brings me to another point I wanted to discuss: AI-balls! We’ve touched on them a few times in abstract, but when examining the intersection of technology and empathy, one would be remiss to neglect the characters who are literally made to be empathic technology. The emotional backbone of AI1 was main character Date’s relationship with his AI-ball partner Aiba, who, while ostensibly invented to be a purely pragmatic tool to aid in his police work, ended up being far more valuable to him as a confidante and surrogate sister figure than as a piece of tech.

It’s funny; the canon considers the Psync machine to be ABIS’s crowning technological achievement, with multiple characters and factions treating access to it as an invaluable, life-changing resource. And yet if the purpose of the Psync machine was a way to simulate empathy by allowing you to literally peer into someone’s subconscious in lieu of having to actually communicate with them, the AI-Balls achieve that goal far more impressively. AINI bequeaths Aiba to Date’s adoptive daughter Mizuki, but it also introduces a new pair of investigator-AI-ball partners: Ryuki and Tama, whose relationship is just as much a mirror of Date and Aiba’s as it is an inversion of it. Like Aiba, Tama provides the seriously-traumatized Ryuki with emotional and therapeutic support, but the way the two interact has far more intimate overtones than we ever saw between Aiba and Date.

Both Tama and Aiba, despite being artificial intelligences, show genuine compassion, concern, guilt, vindictiveness, and pathos – a more honest ‘simulation’ (if you can even call it that with how advanced the two are) of empathy than dream-hopping could ever afford. I would reckon that more emotional and narrative breakthroughs occur from Aiba and Tama conversing with their respective partners than anything they learn from the actual Psyncs, because at the end of the day, that’s how human beings learn and grow! Not from accumulating information, but from developing empathy.

Phoenix: The Masked Woman and the AI-Balls are perhaps the most distilled examples of that paradox of technological advancement you just discussed. Their existence highlights how humans keep creating technological devices or software in their image. Sometimes such creation is done with altruistic intentions, but more often than not there are capitalistic or imperialist benefits in mind (or both). When technology presents opportunities for personal advancement, often many individuals like Chikara or companies absolve themselves of any ethical concerns. Many products, including the computers and consoles we play games on, continue to be made with conflict minerals, for instance (a fact I often feel unsettled about).The utopia or nirvana that techno-solutionism seeks, in the game’s world and our own, is often about avoidance in the guise of offering radical intervention, or pushing the greater responsibilities onto the vulnerable. The Masked Woman’s arc underscores this dynamic and I believe you’re spot on with identifying the users rather than the tech itself as being the cause of her suffering.

I agree that the AI-Balls are much more successful than the Psync machine, with regards to literally being empathic machines. The way that a Psync machine gives detectives a way to surveil a person’s mind makes me think again of Greer’s video essay and a specific paraphrase from it—if you need to walk a mile in someone else’s shoes to understand them, that’s more akin to voyeurism than empathy. There’s a deeply unsettling Psync late in AI1 I’m thinking of (IYKTYK), which maps out this assertion with a pivotal role-reversal and shows the player the potential abuses of being able to delve into a person’s innermost psyche. The relationships between the agents and their AI-Balls keep them balanced and remind them that whilst the suspects do offer a lot of valuable insight for their investigations, they are still human lives you’re tampering with.

Ryuki and Tama’s relationship and its intimacy I find very fascinating, because they are technically in a dom-and-sub (D/s) relationship. Uchikoshi jokingly calls Tama a “dommy mommy” in one interview who motivates Ryuki by exciting him. But putting the cringey language aside, Uchikoshi has portrayed a dynamic that is much more nuanced than the usual D/s misrepresentation we get from pop culture which hyper-focuses on sex. Ryuki and Tama are more mature in their partnership than Aiba and Date, yes, but the core of their relationship is still communication.

While Aiba and Date or Mizuki are playful and tease each other, the latter offering advice in a sisterly way, Tama provides Ryuki with a form of after-care from the more intense scenes of the investigation. There’s a bit of a visual pun with this as well when Tama acts as a director in VR and has Ryuki re-enact “scenes” where the suspects’ actions are complex or unclear. Tama will often flirt during these scenes and although Ryuki may seem irritated or oblivious to her, she encourages him to loosen up and approach the VR reenactments as a sort of structured escape from the main investigation. Yet Tama and Ryuki’s dynamic can be toxic too, with the former willing to help Ryuki even when he goes increasingly rogue from the investigation. And when Tama is offline or unavailable to help Ryuki later on, he becomes emotionally unmoored. There was no “exit strategy” put in place for such instances and I believe ABIS didn’t account for their agents forming such deep attachments to their partners. Just as with Aiba when Date almost loses her in the first game, the ABIS partners are nearly co-dependant on these AI-Balls. They are even part of the agents’ anatomy, a piece of tech that completes them. Two is one, indeed.

Mina: If you had told me years ago that I would one day shed tears over the funny little eyeball hamster woman, I probably wouldn’t have believed you–but then again, maybe I would have, considering Uchikoshi has proven time and time again that he has an immaculate talent for writing complex characters whose disarmingly quirky idiosyncrasies make them instantly-endearing.

I think that’s what it comes down to, at the end of the day. Even if both AI games had poorly-written central mysteries (which they don’t, thankfully), the cast is so charmingly, irresistibly wonderful that I would still enjoy and recommend them to everyone I know. It’s been said that the worst thing one can say about a story is “I don’t care what happens to these people,” and Uchikoshi has a deep understanding of that notion. He’s toyed with making characters intentionally insufferable and unlikeable in the past (see: Dio in Virtue’s Last Reward or Eric in Zero Time Dilemma) but, in my eyes anyway, he’s averted that entirely when it comes to AINI.

While the game absolutely does test the limits of your empathy at times–you mentioned your conflicted thoughts on Komeji earlier, and I personally don’t think I’ll ever be able to get over Lien acting creepy towards teenagers–it also understands that characters need to have those sort of flaws to motivate their personal narratives. It’s a mystery story, so things would be all-too-easy if everyone just cooperated and spilled their guts at first blush, after all. Where AINI truly triumphs though, and what’s kept it at the back of my mind ever since completing it, is that I understand why the characters act in the ways that they do (well, Lien’s inappropriate courtship aside, haha). One of my (admittedly few) criticisms of the first game is that I sometimes had trouble understanding the motivations of certain key players–especially the main antagonist, who seemed to fall into the common writing trap of having villains do things “for the evil” or “because they’re unwell” to avoid giving them a reason which might make them more sympathetic than intended.

AINI’s antagonist, though? I get them. They’re a product of abuse, both emotional and physical, of ideological grooming, and of years of pent-up bitterness, rage, and sorrow. Even if what they’ve done (and what they plan to do) is morally-abhorrent, I can easily understand what drove them to believe it was the correct course of action, and at no point does the game just pull the “they’re insane” excuse. This is a consistency afforded to everyone in the game, from the petty criminals to the well-meaning yet powerless onlookers, to the primary duo of investigators and their AI companions. Even when they’re doing the wrong thing, it makes sense why they’d consider it their best (or only) option.

I mentioned before that while AINI offers a somewhat more linear story than its predecessors, it uses that to leverage how the player’s perception affects their ability to connect with the cast, and I stand by that being a sort of magic trick of writing. There were times while playing this game when I was furious at characters for doing something I perceived as being stupid, illogical, or short-sighted, only to later find out their reasoning for doing it and subsequently feeling my heart shatter within my chest.I care a lot about the weirdos and goobers who inhabit the world of the AI: The Somnium Files duology. This bunch of uncut gems, flawed but brilliant, who together allow the games to shine so brightly.

Uchikoshi’s a writer whom I respect immensely for his ability to constantly tinker with and improve his own style, who takes big swings even when they miss, and always learns from his missteps to ensure that the next experience is even bigger and better than before. I don’t think AI: The Somnium Files – nirvanA Initiative is quite his magnum opus (in fairness, Virtue’s Last Reward is one hell of a high bar) but it’s certainly a contender. And a big part of that, for me anyway, is how easily his lovingly-crafted narrative allowed me to connect with the characters and understand them on a level I haven’t felt for many stories.

The Ryuki Defense Force is always accepting new members, is what I’m saying.

Phoenix: Firstly, I’m joining that force. Secondly, not to mirror you, but I agree that Uchikoshi is masterful at iterative design and storytelling. AINI gets my vote as being one of his top tier games, for sure. There really is something to be said for how he can take very abstract concepts or points of view and communicate them, ludonarratively, to the player in a precise and insightful manner. The main antagonist of AINI is sort of like a reimagined Zero from the Zero Escape series, in my opinion. Like Zero, he’s shrouded in every sense of the word, and for most of the game you don’t even know what his true voice sounds like! He’s capable of making unspeakable decisions that could affect millions of lives or more. But that’s where the comparison ends. Zero is more of a force of nature than he is a person. But AINI’s protagonist is a human through and through and acts upon the world from a believable (if speculative in some regards) history of trauma.

I keep thinking of how Uchikoshi was quoted saying that there should be more “static and heartrending” games and he’s definitely been following that brief here. Games may not be empathy machines, but I’d be shocked if someone couldn’t find at least one of these “uncut gems” of characters worthy of their empathy.

Conclusion (Mina): AI: The Somnium Files – nirvanA Initiative is a game about a lot of things. It’s about love. It’s about hate. It’s about seeking the truth. It’s about finding comfort in lies. It’s about how technology can separate us from compassion and empathy. It’s about how technology can bring us closer to understanding each other than ever before. It’s about the duality of all of the above. And that’s what makes it such a rock-solid narrative, and one of the best games to release last year.

I said earlier that I felt like Uchikoshi (and director Akira Okada) managed to pull off a ‘magic trick’ with AINI, and I stand by that very loaded metaphor. Not everyone’s going to like this game or its characters, but I almost feel like that’s by design. It’s a matter of perspective, you see–the game isn’t telling you what to think about any of it, it’s merely giving you the tools and information to allow you to come to your own conclusion. It’s testing the player’s empathy, while at the same time daring you to get invested so that it can make you cry and cheer and get lost in thought pondering the answers to some of the deeper questions it poses.

We know that it at least worked on the two of us, right?

If you like what we do here at Uppercut, consider supporting us on Patreon. Supporters at the $5+ tiers get access to written content early.