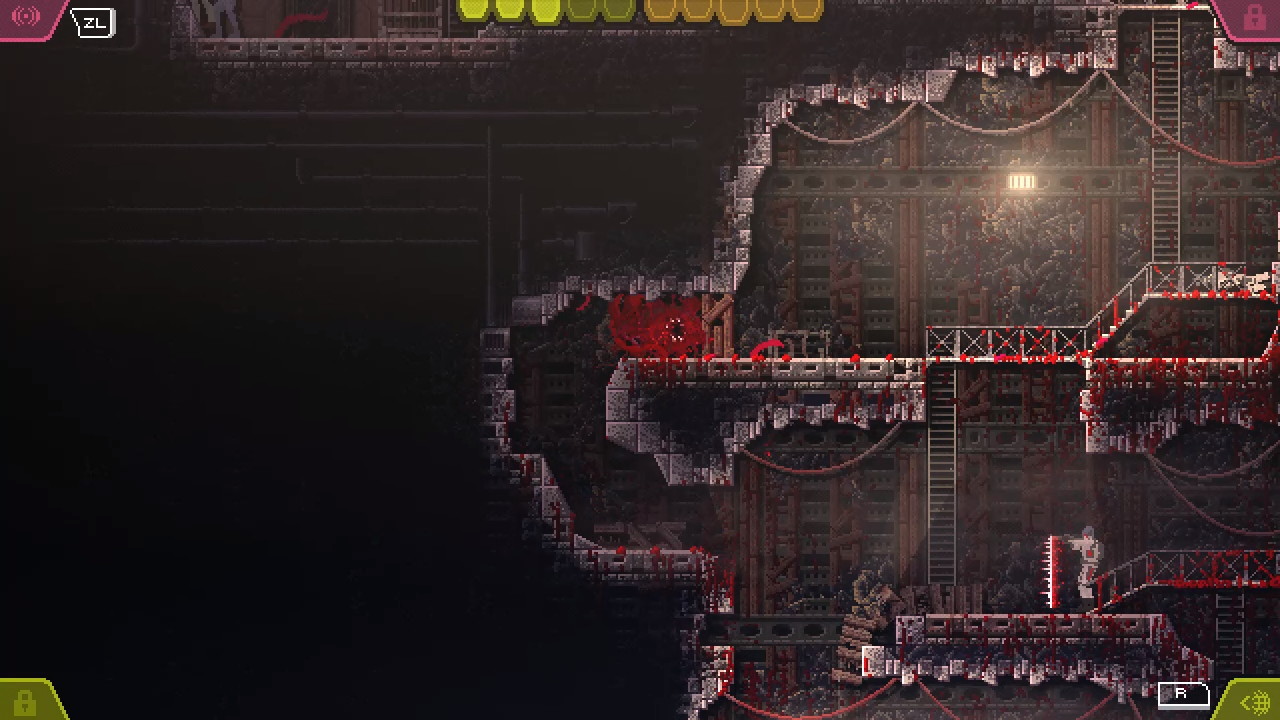

Screenshot provided by author

Alien Architecture: Carrion and How We Negotiate With a Hostile World

In Phobia Game Studio’s 2020 “reverse horror game,” Carrion, the player controls a monstrous alien collection of viscera, teeth, and tentacles as it attempts to escape from Relith Science’s subterranean research facility. Over the course of its escape, the creature slings through sewers, tears open air ducts, and hoists hapless facility staff into the dark corners of laboratories. Amidst the relatively mundane hallways, vents, and rooms of Relith, the creature moves unlike any video game protagonist I can recall. Its relationship to this space is unique in all of the alternative ways it finds to occupy it. By letting us observe an alien creature in a human setting Carrion lets us reevaluate that setting and how it shapes us as much as we shaped it.

In his book The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception, ecologist James J. Gibson coined the term “affordances” and defines it as “what [an environment] offers the animal, what it provides or furnishes, whether for good or ill.” An affordance is an emergent synthesis between each individual organism and the qualities of its environment. Within the subterranean depths of Carrion we see how the facility in which the game is set has been designed primarily with human researchers in mind. The doors, elevators, ladders, and hallways make themselves readily available to fleeing humans. But this lack of design consideration does not leave the alien creature lost; it simply finds alternate ways to encounter the space and new affordances emerge.

The monster often comes upon doors that will never open, elevators that will never move, windows that will never break. The core loop of the game is finding ways around these immovable barriers. Often, the solution is violently opening a vent or sewer grate, but other times the obstacle forces the monster to get more crafty. As the game progresses, the creature grows through three sizes, each with its own mutant powers to confront different challenges, from invisibility to an explosive-resistant coating. In later levels, the game revolves around managing three size levels to approach each puzzle with the right tool. These gameplay interactions foreground the way that an organism’s individual body shapes what its environment affords at any given moment. However, even in its most basic movements, Carrion’s monster occupies the space in alien ways. It keeps almost exclusively to corners and walls, reaching out with thrumming tentacles until it finds purchase on another surface. While small, the creature whips through the dark vents and pipes but as it gets larger, its tentacles drag a hulking mass of tissue down hallways. The creature is in a constant state of negotiation and renegotiation with its environment and its own biology.

When Gibson discusses “environments” it should be noted that these are not strictly natural worlds. The designed environments of the modern world, whether they be physical architectural structures or digital platforms, provide as many affordances to the organisms and users that house them as a natural ecosystem. On display within Carrion is an intensely designed and curated space, which is why the architecture affords so much to the intended human residents of the facility. However with the presence of a designer and an intended user, affordances change. Sociologist Harvey Molotch writes about the influence that designed objects have on human evolution in his chapter Objects in Society, “Objects forge the body and vice versa… we are more than just tool users.” As humans evolve with our tools and other designed objects, we grow dependent on them over generations as our bodies adapt and we need chairs as our musculature changes, or fire to extract nutrients from meat. Affordances provide a mechanism for this dependence to develop. You could even say these tools afford dependency. Playing Carrion is like watching the abridged development of a tool-species. The monster interfaces with this alien place and adapts, eventually becoming reliant on these halls for its food and for exposing it to new challenges and mutations to meet those challenges that prepare it for its final escape.

Something else develops from this process of mutual evolution with our tools, however. Molotch notes that these changes are not strictly biological, but also sociological. When a group becomes dependent on a tool, they classify those who do not (or even cannot) use that same tool as deviant or primitive by comparison. For example, Molotch notes the way that fidgety children who have trouble sitting for long periods of time are pathologized as they are told they “can’t sit still.” Part of the threat that Carrion’s creature poses to the humans of Relith Science are the different ways it can move through the spaces that they either will not or cannot access. The power fantasy of being a dangerous body horror monster is mapped onto these transgressions of spatial and social boundaries.

Levels in Carrion are constructed such that you are incentivised to find alternate ways to get behind security systems, either by accessing sewers or air vents. Directly entering combat encounters more often than not leads to a failstate where the monster dies under machine gun fire, or actual fire. That is only up until a certain point, however. As the monster grows bigger it also gains a higher life pool and more consistent direct attacks. It becomes harder to maneuver through these tight hiding places that previously lent a strategic advantage. When the monster has to compress its form into an air duct rather than slipping its entire mass through it at will, it exposes itself to a greater risk of lethal damage. Manipulating the creature at that size with a joystick in such small spaces frustrates what was a safe, smart, and tactical way to play. What previously was a death sentence becomes the easiest solution: breaking open the main door and lashing out with tentacles, knowing that the bodies you leave in your wake will heal up any damage you took along the way.

The design of the game space fosters new behaviors in Carrion’s creature (and us as its pilots) as its physicality changes. In a way, this space starts to standardize the biology and the actions of the monster. In his lecture Society Must Be Defended French philosopher Michel Foucault outlines the concept of “biopower” and how it differs from other forms of power: “It is, in a word, a matter of taking control of life and the biological processes of man-as-species and of ensuring that they are not disciplined, but regularized.” By the end of Carrion all of the guns and fire at the disposal of the shadowy Relith Science corporation cannot stop the monster from escaping. But the facility has changed it. Within Carrion, design serves as another axis along which control via biopower is exerted.

The creature’s very biology is a resource to be churned through and used to complete each puzzle. It is a bargaining chip in the negotiation with a hostile environment. In order to survive, the creature has to be malleable and adapt its body. The game’s use of backtracking to previously inaccessible areas with the creature’s new mutations emphasizes this further. The final door that the creature opens to its escape is first seen early in the game, well before any of its mutations have been incorporated. In Carrion’s final moments the creature makes its escape not by crashing and breaking through the facility’s gates but by mutating one last time, allowing it to fully assume the biological identity of a human, so much so that it tricks a number of bioscanners on its final ascent to the surface. A biopolitical lens sees that here, the “deviance” is not just disciplined out of the alien as it shifts to becoming completely human, it has been designed out so that the creature willing standardizes its own biology. This is not the end of the monster, at least nothing in the game suggests that, as the city in the background foreshadows more bloody havoc the creature will wreak on Earth now that it is free, but it is undeniable that this is a different monster than what starts the game. Even as adaptation is liberatory, it is also confining.

By its conclusion, Carrion develops into a parable about the ways that our tools are not simply designed by us, but how what we design designs us back. As Gibson puts it, “An affordance cuts across the dichotomy of subjective-objective and helps us to understand its inadequacy.” Carrion gives us a way to think about this breakdown of the subject-object boundary and how it is used not just to police but rather to design the alien out of us.

Wow wow wow what a great essay! It’s interesting to think of Carrion through the lens of environments and the ways humans who they weren’t designed for are forced to adapt to them, find different ways through of around them or just die. From the simplest examples of needing to duck if a doorframe is too short for you to those stories of wheelchair activist going out and smashing ramps into sidewalks at night to force the environment to be accessible to them. Great work!