Image Source: Nerial Limited

Card Shark and Justifiable Identity

Early on in Card Shark, the protagonist, a mute boy called Eugene, meets a man named Ireneo Funes. Ireneo is, like many of the game’s characters, an intelligent con man with a knack for card tricks. He’s an old friend of Eugene’s mentor, the Comte de Saint Germain, and he quickly befriends Eugene as well.

A bit further on in the game, you encounter a high society woman, the Baronnesse de Beauregard. The Comte and the Baronnesse share a mildly flirtatious rapport, although the Comte privately remarks to Eugene that he finds the woman unattractive.

Shortly after each of these characters is introduced, the player makes a startling discovery: the Baronnesse de Beauregard is Ireneo Funes in disguise. At this point in my first playthrough, I thought I understood the twist. Ireneo, I assumed, was a gay man disguising himself as a woman to become closer to the Comte. This is the kind of right-hearted but wrong-headed queer character work that I can reason with emotionally. It makes sense to me.

As it turns out, though, Card Shark hosts an entirely different, similarly tired type of right-hearted but wrong-headed queer character work. Ireneo is not a man disguising himself as a woman for love, nor is the Baronnesse the classic woman disguising herself as a man for higher social standing (pointedly, Ireneo travels with a Romani camp that finds itself on the lowest rung of French society). In fact, both Ireneo Funes and the Baronnesse de Beauregard are pseudonyms for S.W. Erdnase. Erdnase is no more comfortable as a man than as a woman, and while the word “genderfluid” is never expressly uttered, the implication is rather heavy.

Most characters in Card Shark are named after real-life historical figures (although the numbers have been fudged a bit to get everyone into early modern France). Erdnase is one such figure, named for the author of The Expert at the Card Table, a notorious guide to cheating at cards. The name “S.W. Erdnase” is commonly thought to be a pseudonym, given that nearly nothing is known about the writer – and here is where my troubles with Card Shark’s S.W. Erdnase arise.

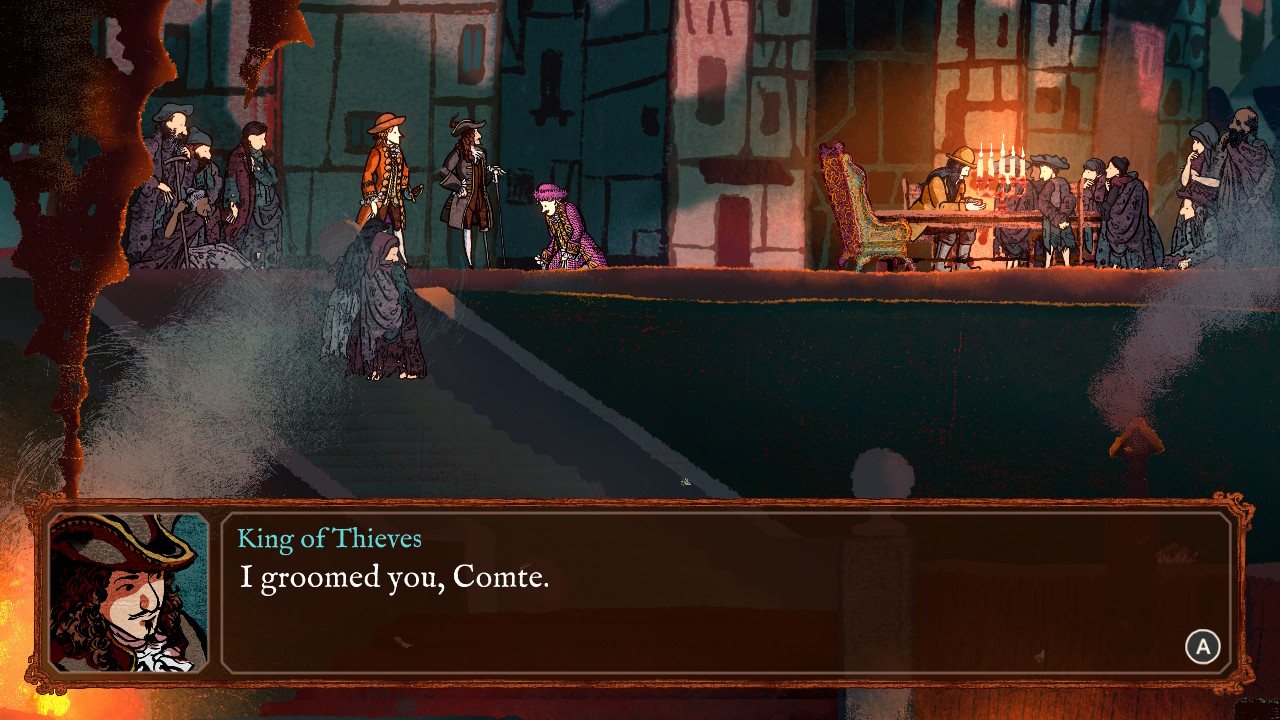

I could write something about the way Erdnase conspicuously plays into troublesome anti-trans rhetoric. Here, after all, is one of history’s most notorious deceivers, reimagined as a genderfluid trickster. Ireneo Funes is named for a fictional character, and the Baronnesse de Beauregard is not named for anyone I can find any record of. In a game full of historic figures, it seems notable that Erdnase would use two mostly-fabricated titles. Erdnase is, after all, a liar. This may not be a literal man-in-a-dress lying his way into private spaces, but the comparison draws itself. In the end, Erdnase is revealed to have orchestrated several key elements of the plot, and the image of the trans manipulator pulling the strings of society from behind the scenes is none too pleasant.

To be honest, though, while all of that is certainly upsetting, I don’t mind it very much. Card Shark has no shortage of liars and string-pullers, and while the dynamics at play are certainly different when writing non-cis characters, I don’t think there’s anything inherently wrong with a mastermind who happens to be genderfluid. I don’t feel any malice in the writing of the character, and I find that the game’s theoretically harmful ideas aren’t necessarily problematic in practice. In a sea of liars and monsters, Erdnase is ultimately one of the less evil figures, and the game shows enough love to the proverbial outsider that its good intentions mostly pierce through its shoddy execution.

What really frustrates me is the narrative justification for Erdnase’s identity. The real life Erdnase is a mysterious figure, and over a century after the publication of The Expert at the Card Table, we still don’t really know who they were. It stands to reason, then, that in adaptation, one would want to present Erdnase with an air of mystery, pointedly avoiding any direct statements about their identity. Ergo, the genderfluid Erdnase.

Here’s the thing, though: being genderfluid is not abstracting the concept of gender. Queer people are not ephemeral things that exist outside of the notion of identity. “S.W. Erdnase is genderfluid” is exactly as concrete a statement as “S.W. Erdnase is a man,” the presumed basis for most theories on the writer’s identity. It seems like Card Shark is fairly incurious about what gender actually means to Erdnase, though.

Card Shark’s textual analysis of Erdnase’s identity is limited to a couple of snipey comments aimed at small-minded fools; one character, for example, can’t decide whether to address Erdnase as “sir” or “ma’am,” to which she says, “You can call me your majesty.” At one point, when the Baronnesse is revealed to be Erdnase, she notes, “I am still no gentleman.” This is about the extent to which Card Shark is willing to engage with the character’s queerness – through terse comments and vaguely progressive exchanges. It’s cathartic, broadly speaking, but it’s not especially meaningful.

The thought process behind the decision to make Erdnase genderfluid feels so clear. It seems to go: he is mysterious and deceitful, so he must wear many masks, so he must not be cis. Erdnase’s narrative positioning calls for queerness as a writing flourish, something of a textual shorthand for “mystery.” But queer people don’t exist for the benefit of a better mystery. In fact, queer people don’t exist for the benefit of better writing at all.

Think back with me on Quina Quen, the voracious non-binary party member from Final Fantasy IX. Quina is a Qu, a genderless species in the world of the game. I have a weird relationship with Quina. I think it’s kind of interesting that s/he uses a set of neopronouns (likely an unintentional decision), and I ultimately find him to be a fun character – for whatever it’s worth, I feel a similar way about Card Shark’s Erdnase.

But I can’t help feeling frustrated every time I see a non-binary character from a species with no concept of gender. Non-binary humans exist, and they exist in the middle of a species with a very firm concept of gender. “Genderless alien/fantasy being” is an almost-useful allegorical shorthand, but it’s often one that forgets about the material reality of real people. In the case of Quina, “non-binary” doesn’t really mean anything other than “weird.” It’s one of a million ways that the game paints the character as “different,” but it’s also a way that the game rejects real queer humans.

S.W. Erdnase, blessedly, is a person. In fact, Erdnase is something of the anti-Quina. She moves in the very rigid confines of early modern French society, and she stands in stark opposition to those confines. But, as is the case for many, many queer (and especially transgender) characters, Erdnase’s identity is still a load-bearing character trait. Erdnase is not simply genderfluid, Erdnase is genderfluid for a reason. Her queerness is neatly narratively justified.

I am a transgender woman. I exist in a world that is very conscious of gender, one full of constant debates on that very topic. I am not a historically mysterious figure. There is no way to narratively square my life with my queer identity. I suspect that this is the case for most real human beings – if only the world could stop trying to justify us.

If you like what we do here at Uppercut, consider supporting us on Patreon. Supporters at the $5+ tiers get access to written content early.