Image Source: Blackbird Interactive

Hardspace Shipbreaker: Seizing the Means

The ship bears a mass of 300 tons. It is photographed in first person, by a laborer who will achieve its deconstruction. They are both afloat in a space yard, the enclosure anchored to a constellation of its kind, itself suspended in void. The vessel has seen countless berths and passengers, but now the worker will feed it to the furnace, whose disintegrating heat will return it to raw material. Something into nothing into something again, a process so basic it echoes the universe’s creation. Someone has a legal claim on that miracle. The wonder is, not that the field of stars is so vast, but that man has financially discriminated it.

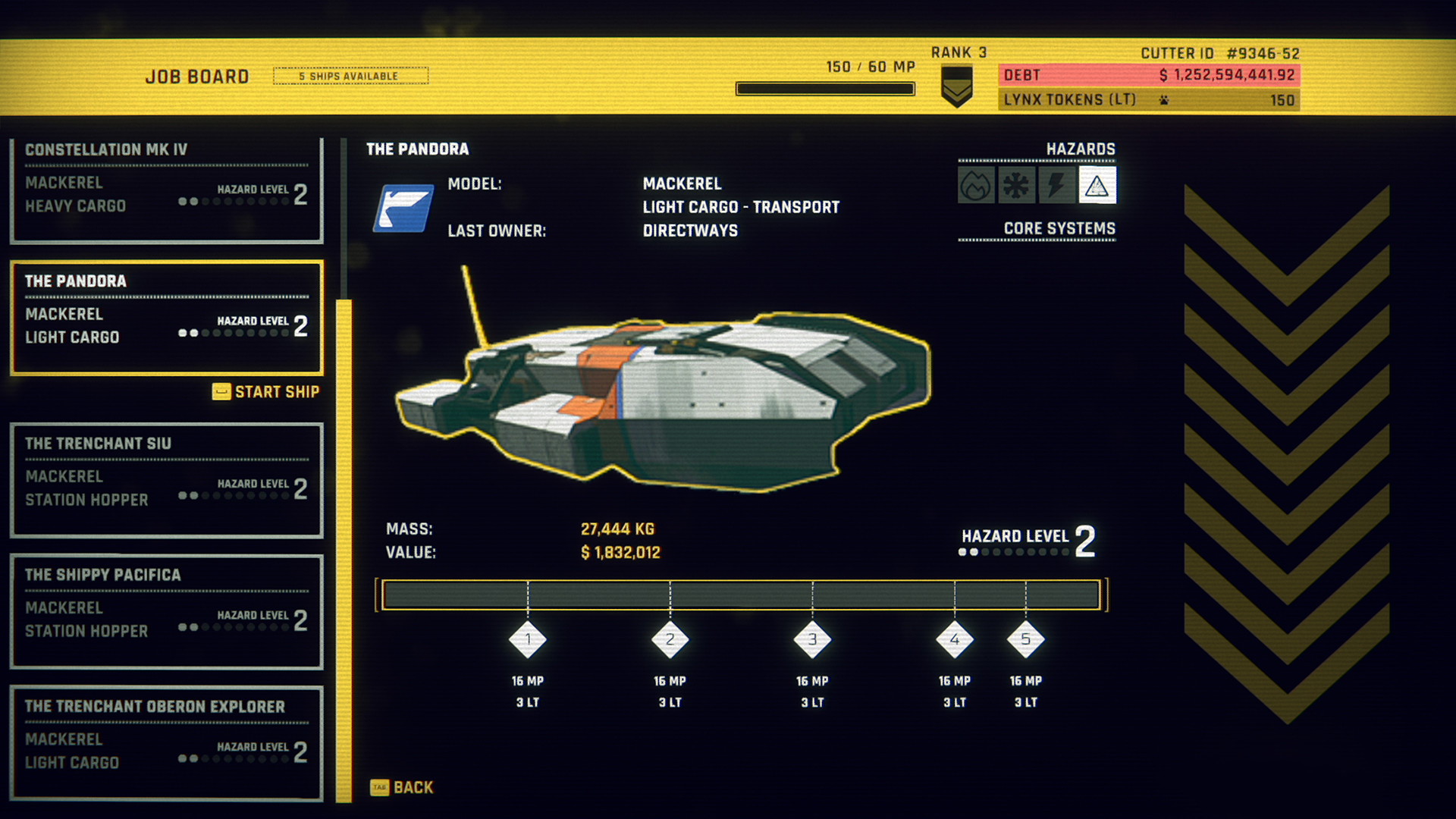

Hardspace: Shipbreaker takes place in outer space; it allows us to wield awesome forces, it lets us touch a nuclear reactor. It is not a game of violent empowerment, instead complicating its take on the video game fantastical with a social-realist premise. The ship, the worker, and indeed the patented technological processes involved are under ownership. The game begins with a contract, a buy-in that shackles us to a company through heavy debt so we will do a job we don’t want to.

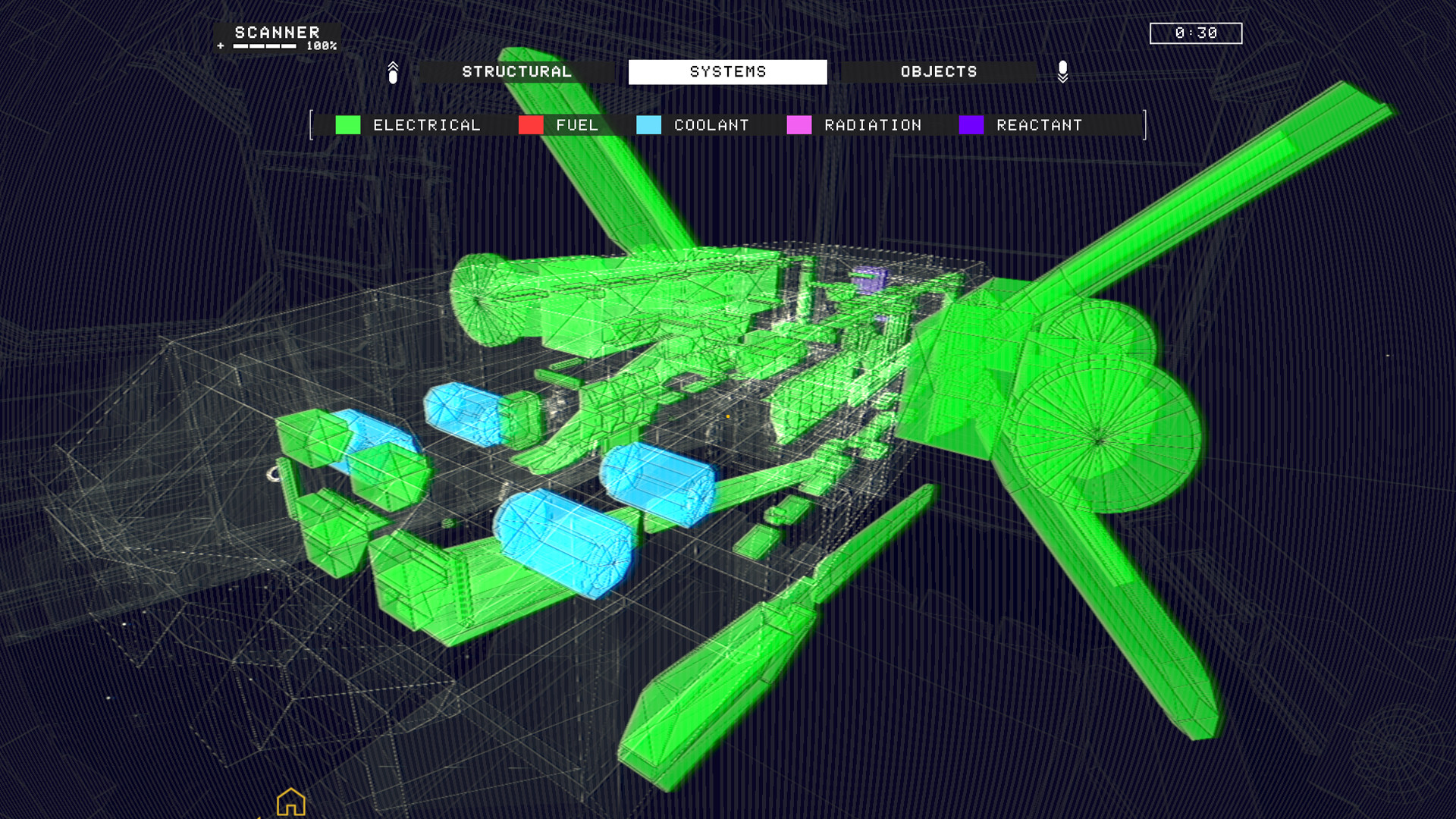

The work is dangerous. It takes place in open space, asking us to move untethered near roaring furnaces. The ships feature live electrical networks, fuel lines, engines of varying degree of complexity and risk. Most ships come pressurized, so letting the outside in can turn you inside out. However satisfying the play, death is always close, but never in a hurry, so when it happens it has that car crash quality of rattling you in the bent up machinery of what was a smooth ride.

To help us survive, the company supplies us with an endless slew of replacements, clones of us, should we get crushed during a violent depressurization, electrocute ourselves, or asphyxiate on the way to purchasing a new can of O2. But the clones aren’t free. Each one adds to the debt we need to clear before the end of the game. As with any financial disincentive, we can infer the real assumption behind it, the belief that free clones are less effective at preventing death than debt-clones.

The absurdity of buying into our labor is present everywhere in more indirect ways. Taking out a loan to buy a car to do a job to pay the loan we bought the car with, for instance. Shipbreaker makes this its method, asking us to buy our own fuel and oxygen. In life, food and shelter are primary motivators of labor. In Shipbreaker, avoiding death by exposure is the original motivation of doing a job that causes death by exposure. How can we explain this Kafkaesque circularity? Debt begets death begets debt, something into nothing into something again.

Shipbreaker doesn’t just drive toward the oft stated evils of late stage capitalism, but goes beyond. Its play draws from simulation. We’re handed tools. What we do with them comes from us. Because of this fundamentally open approach, the game supports two ideas.

1) There is no such thing as unskilled labor. Player progression is measured in how well the mechanics are used, not how much mass our tools can move. Techniques we first employ cautiously are slowly perfected. The cumbersome early toil gives way to routine sequences of self-organized techniques and sub-tasks. Coming up with novel methods for solving increasingly difficult problems becomes one of the game’s main praxes because it allows the player to demonstrate the idea which follows from it, that far from any company it is we who are the true authors of our work, and thus, 2) we who own our labor.

This is an important idea, because at the point when our array of tools and techniques is increasing along with our mastery, a complication takes place. The workers form a union, and the company sends a hound to break them.

His name is Hal and he is a middle manager. On paper, a manager is an elevated laborer capable of organizing the workplace. In practice, they’re often the kind of legendary asshole who uses the work schedule like a cattle prod, and in that image you will find Hal, the patron saint of questioning maternal leave and begging for the CEO’s job on Twitter. Hal’s role in the narrative is to communicate something all employees know and resent: The feeling of having your work invaded by a vicious micromanager who is both stupid and untouchable.

Hal’s stated mission isn’t ideological, however. He’s been innocently tasked to put us back on track, get those numbers up, and hit those quotas. That is, to keep us too busy, exhausted, and intimidated to forge on. Soon enough, we’re taking more risks more often, using unfamiliar equipment on more dangerous ships. While we figure out localized explosives, Hal’s dulcet tones join those of our coworkers, his regurgitated slogans promising that we could be in his spot one day, if we work hard enough.

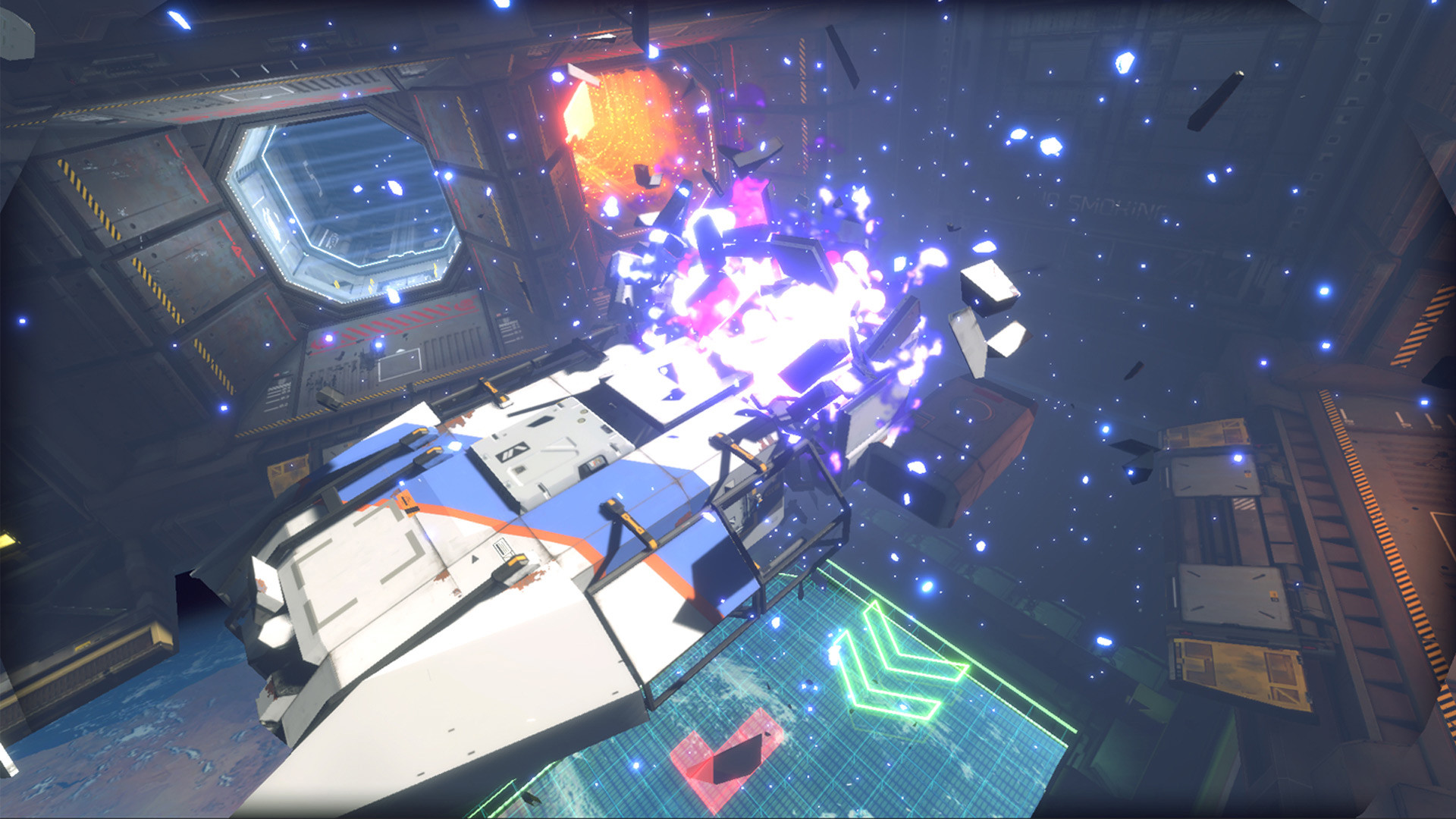

From here, the game’s ultimate message becomes apparent. A labor union is not only possible, its organized resistance makes up the only way to confront what Hal represents. Its first goal is to combat its immediate dissolution under pressure. We achieve this in the story’s climax, when we once again exploit the main economic principle of the game, that what blows up is also what sells, but not at the same time.

In a set piece called Industrial Action, we test that assertion. We trigger every hazard, send precious electronics to the furnace and metal frames careening into the void. Conclusion: Salvage rapidly depreciates after nuclear meltdown. Cathartic as it can be to destroy a ship while management watches, the real effect is on Hal’s performance report. This small tyrant desperately needs us to make him look good but forgets something we’re learning for the first time: The worker controls the workplace, and the hand that holds the laser cutter tells the beam where to go.

The union storyline ends in total victory, something hardly guaranteed in our actual lives. Company retaliation is real and highly effective. That doesn’t mean Shipbreaker deals in the catharsis of a brief fantasy. Regardless of the outcome, workers need the sword and shield of collective bargaining and organized action. Shipbreaker places this truth in its mechanical action, showing through nothing more than play that we can take ownership of our destiny.

##

The labor movement is an emergence — a moment in which a pattern becomes clear from events that were previously unconnected in one’s vision. A labor union is born in countless one-on-ones, lunchtime meetings, day long bargaining sessions, late night strategy brainstorms, quick catch ups in the hallway, coffee shop meetups to compare notes, and moments where you realize, just when you thought were done for the week, it’s time for one-on-ones again. The movement is born from that pattern repeated countless times over. Sometimes, I find it hard to remember to do union work on top of the work I have to do for my day job and the other countless little tasks needed to keep myself alive. Sometimes, I find it hard to remember there was a time before I did union work. Being in the middle of a campaign is a little like being Jonah — a very tired and over caffeinated Jonah, in my case — in the middle of a whale in the middle of a pod of whales in the middle of the ocean — you have a role to play but you’re not the one doing the steering.

In Shipbreaker you’re not the one doing the steering, either. Your life in-game is a lonely pattern of shifts in a private (and privatized) shipyard. You get up, you check your tools, you spend fifteen minutes breaking apart and breaking open ships which are the husks of industries long since sucked dry by capitalism’s far future. The union story finds you, —grows around you, —while you listen and work and say nothing. It is others who write the words that you can read in your terminal’s inbox, and your colleague Lou continually raises the topic of unionization on team comms. But that doesn’t mean you don’t have a role to play.

The game pushes you towards the twin goals of paying off your debt and taking back what you can from the isolated misery in which Lynx Corporation has trapped you. Sometimes, these are one and the same, and sometimes, they diverge as when you destroy valuable equipment for its parts or when avoiding dying (and the associated costs) means waiting until your next shift to finish demolishing this ship. Both paths are dreams of freedom, dreams of escaping the limited options you have been given. And both rely on you showing up, and trying again, and getting better, and braver. Resistance which once felt impossible becomes easy. Soon enough it’s you who are showing up for Lou and not the other way around.

Sometimes, I’m scared that I am not very good at labor organizing — two years and change and I’m still not able to keep my face neutral sitting across the table from management. I still sometimes lose control of my volume when talking to a colleague whose worries I feel are cowardly (but which I know it’s important to listen to anyway). I still regularly forget about weekly meetings whose times never change. I wish I was calmer and more measured, and I wish I was better at following up with people when I intend to. I care about organizing — I think it matters more than almost anything else right now — and that’s why every misstep, no matter how small, stings me as painfully as a wasp. But the truth is, what labor needs isn’t a perfect organizer, but many people willing to get up each day and do what they can –– sometimes falling a little short, sometimes succeeding, but always trying again. The best organizer is the one who keeps showing up, because there is always someone to show up for and also because, without fail, one day that person will be you.

Sometimes, I worry that I’m not very good at video games — I rarely roll credits on them or even reach their final chapters. Usually, I stall out somewhere around mid-game having gotten too frustrated with my skill ceiling or otherwise having lost interest in favor of some newer, shinier thing. I wish I had slightly better control over my hands. I wish I was less at the mercy of my ADHD.

But just as labor organizing doesn’t care how good you are at it, Shipbreaker doesn’t care how good you are at video games. Events in the unfolding story occur not after skill checks but after benchmarks, benchmarks you can hit if you try and then try again. The days (real and in-game) mark out the work you do, as well as your colleagues’ occasional but welcome reminders that you aren’t alone. Shipbreaker is a remarkably lonely game — the only person you ever see outside of headshots is your own shadow — but it isn’t one unpunctuated by human kindness or by dreams shared. One shipbreaker tells you he dreams of working with animals. Lou confesses she dreams of a worker owned cooperative. And sometimes, the only person you talk to is Hal, both incompetent and efficacious, and so, so painfully familiar to everyone who’s ever worked any job at all. The steady rhythm of the play and the challenge of getting better, faster, learning more, are what make me come back. But it is these moments of connection that keep the play bright.

I would be remiss not to note that you can get better at organizing in just the same way. You can try to perfect routine tasks. You can iron out inefficiencies here and there. You can try and fail and try and fail and try again. There’s a guy I know who was in three failed organizing campaigns before our successful one. But you wouldn’t know the ratio of success to failure if he didn’t tell you. His well studied patience, which all expert organizers exude in some measure, speaks to a tireless determination and a dream of collective freedom. Managers like Hal might say that leading people is a perfected art — an art which they are naturally the apotheosis of — but anybody who tells you that is selling something.

I recently quit my job, but before that I hadn’t seen any of my coworkers for three years. We had done all our organizing over Zoom and the good old telephone. I talked to people about the union before they were more than a tiny slack icon. Sometimes we’d be organizing not a sea of faces, but a sea of no-video squares which created their own deep space field of black and grey. At the start of the pandemic I lived alone. There were days when the only voice I heard was that of my incompetent and transphobic boss who believed he was god’s gift to me as a mentor. There were other days when the only words I spoke were about the union. Sometimes I would climb out of my basement apartment and sit on the back steps of my landlady’s back porch and smoke cigarettes and stare at the lightning bugs. Sometimes this was the only time I stepped outside for weeks.

It was a remarkably lonely time,–but it wasn’t one unpunctuated by human kindness or by dreams shared. A coworker told me about a time she went hiking with her dad before she had to stop seeing him because he’s immunocompromised. A friend told me about how he held an organizing meeting in his backyard on a windy day just so they could feel each other’s energy. We dreamt together of a time when things were better and we knew how to work and be together and be healthy — something that all the characters in Shipbreaker also long for. Though, their isolation is taken to an even more stark extreme, separated as they are not by a pandemic but by hard vacuum.

Almost a decade prior to that summer, I sat in a flat bottomed boat and watched the emergence of a pattern from the random blinking of lighting bugs along a river in Thailand — one by one little lights appeared out of the dusk and alighted on branches, showing up out of nowhere, to try — one evening succeeding — to blink together. They transformed that night from merely magical to sublime with the strange suddenness of their organization. I listened to my coworkers map social connections in our department and I looked at those fireflies and wondered how close me and the other unit members, me and the other movement members were from blinking in sync and transforming something just as fully.

Hardspace: Shipbreaker isn’t just about union organizing, it feels like it too. And never so much as when you listen to your coworkers chatter in your ears about what animals might be like and, while doing so, look up from your tools to see the pulse of the interplanetary gate and beyond that the limitless stars which blink like fireflies in the deep distance.

If you like what we do here at Uppercut, consider supporting us on Patreon. Supporters at the $5+ tiers get access to written content early.