Provided by Thomas van den Berg

Cloud Gardens: Growth Through Letting Go

Imagine the steel outline of a local bank, glass windows and doors smudged with mud and moss. Tents crowd the lobby. Rich odors of chard and parsnips waft from pots and pans over kerosene stoves. There’s a vegetable garden in the back, a few goats tied to a makeshift wooden fence, their flesh reserved for feast days. As if a meat-filled stomach might make you too drowsy to remember the times before. So much lost to the fires and earthquakes, twin cataclysms of an abandoned Earth.

Imagine a flotilla of sailboats, bobbing on the Atlantic Ocean. The sails were long ago stripped from the masts, repurposed as tethers to tie the boats together. It’s a makeshift aquatic colony. The larger boats, once the toys of hedge fund managers, are now communal vessels: one’s a daycare, filled with the sounds of children playing; another’s a library, its decks crammed with books, magazines, and maps. Today, everyone’s heading to the largest ship, the colony’s social hub. They’re finally voting on a name for this drifting remainder of civilization.

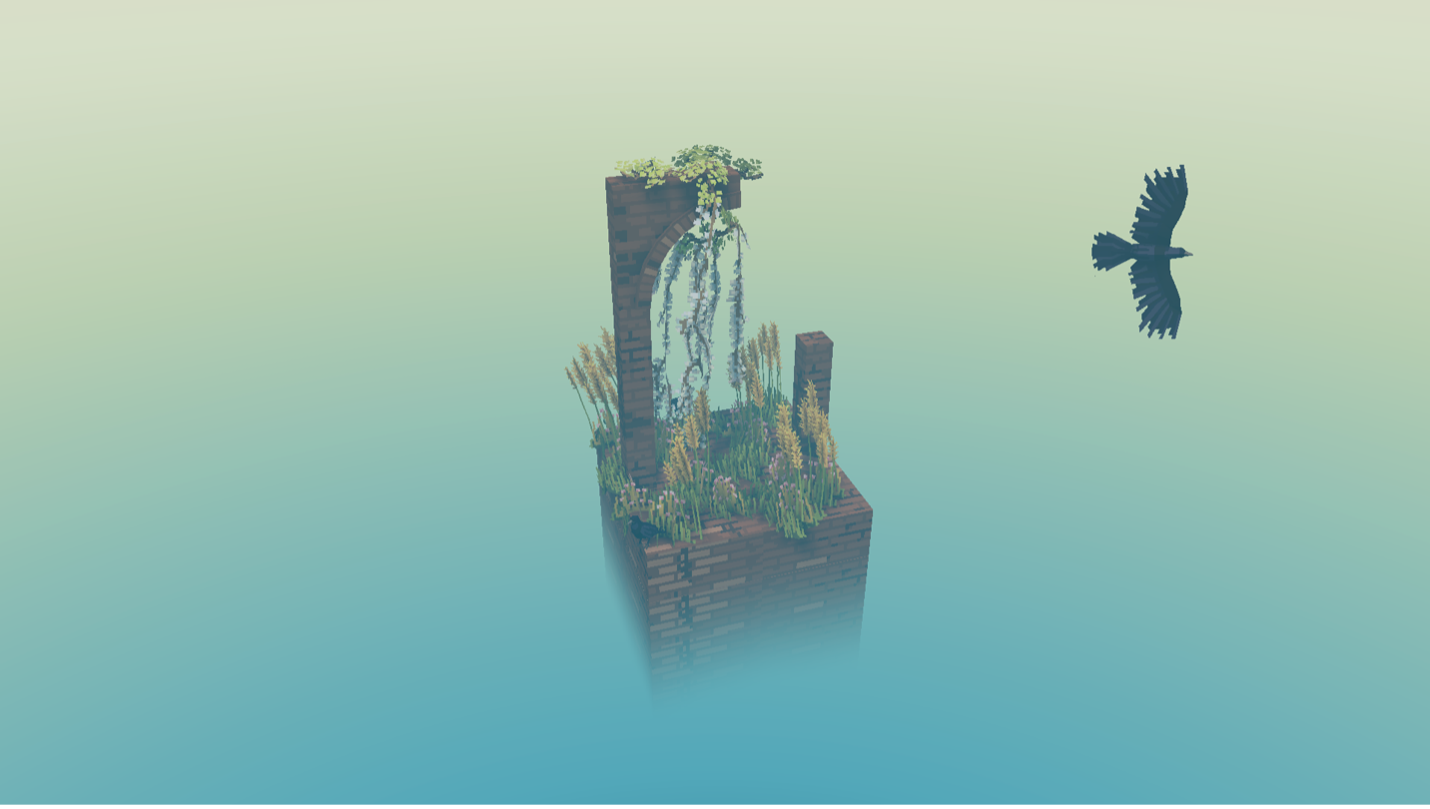

Or, imagine no one, not a human in sight. Only broken pavement, a rusty chain-link fence, a shopping cart warped out of shape, and a tangle of thick green vines. A bird lands on the fence, then another one. They loiter; their heads swivel in search of food. They fly off. Flowers burst from the vines. Seeds waft down. A zig zag of thorny shrubs erupt from the ground.

This is Cloud Gardens, released on PC and Xbox in 2021, developed by Thomas van den Berg (also known as noio, best known for designing the Kingdom series of side-scrolling strategy games).

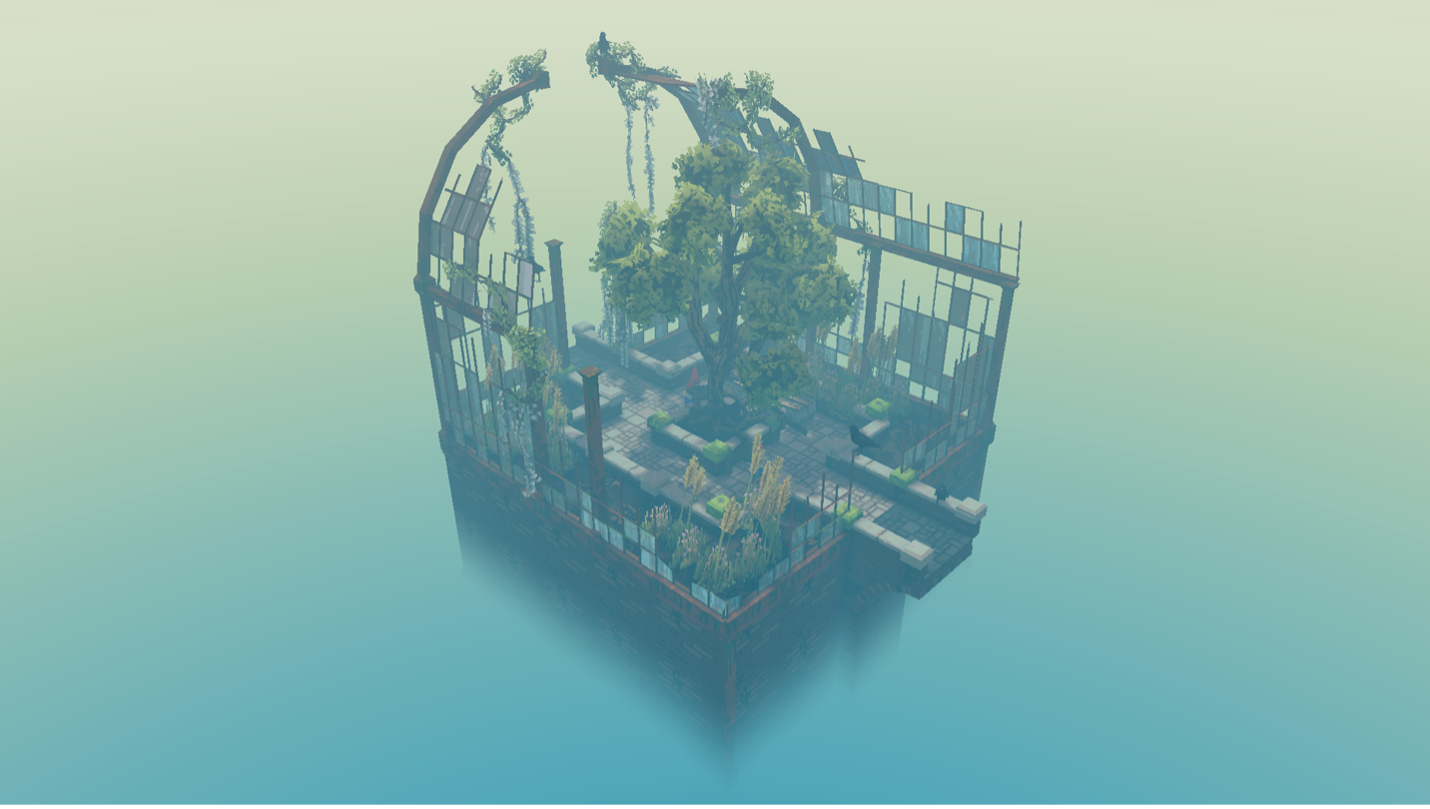

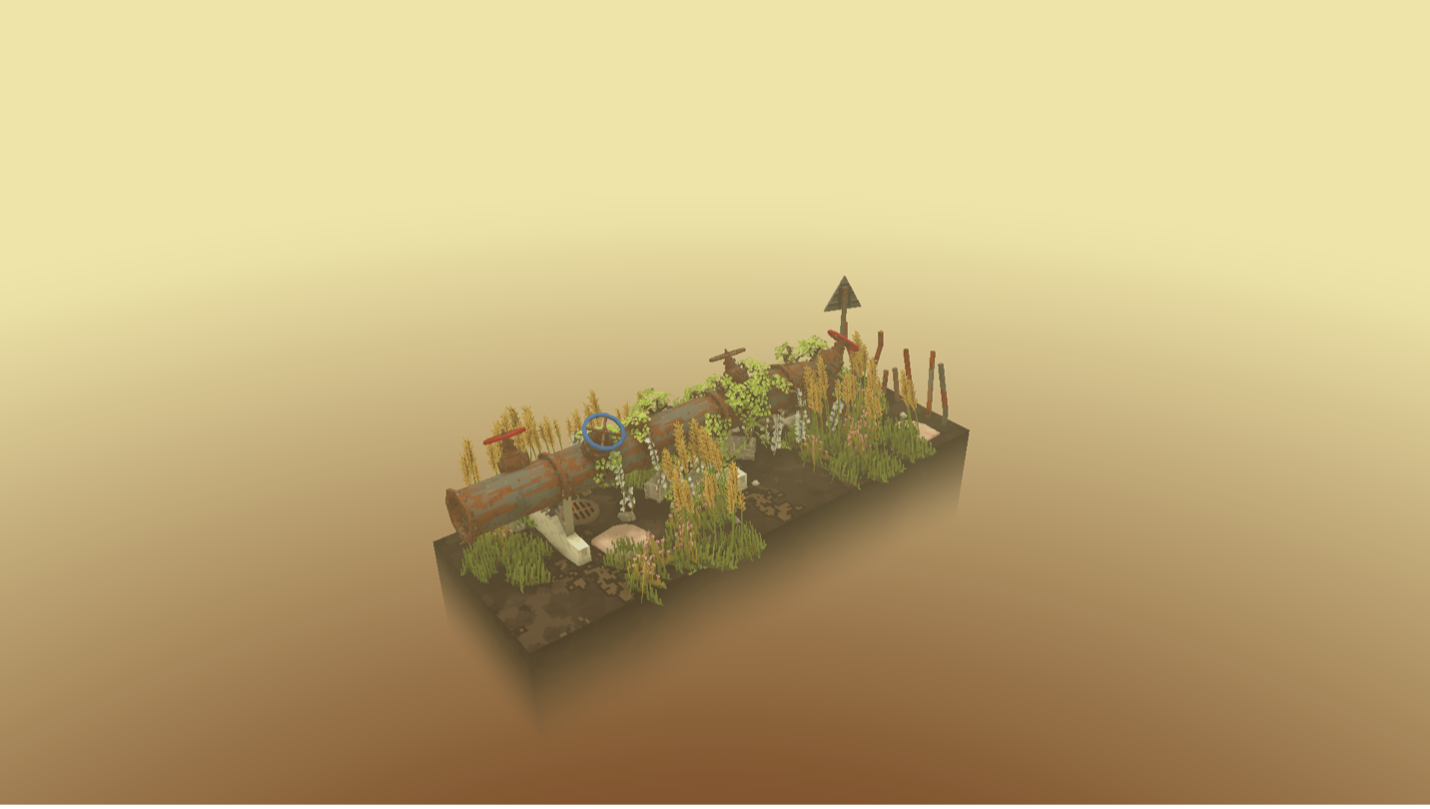

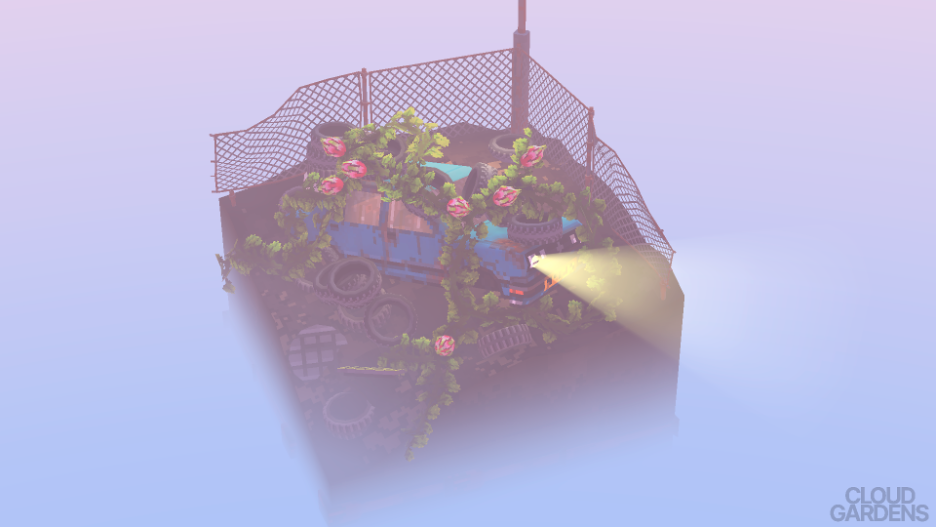

Cloud Gardens is a quiet, post-apocalyptic gardening sim. It’s Stardew Valley after human extinction, Farming Simulator in the ruins of capitalism. Cloud Gardens is also a puzzle game. The game presents its post-apocalyptic world in a series of isometric dioramas, each one brimming with rubble and refuse, broken things waiting to be taken over by plant life. Each level of the campaign asks you to achieve a certain threshold of greenery by strategically placing a limited number of seeds, as well as everyday objects like shopping carts or street signs. A vine might tumble effortlessly down a street sign, a shrub erupts with rough grace from a discarded tire. The trick lies in proximity and contiguity, in planting a seed where it might easily climb from an artifact to its neighbor. Plant your garden well enough and seeds will form, allowing you to sow even more vegetation in a post-apocalyptic loop of botanical splendor.

You can “beat” a level of Cloud Gardens, but there’s no escaping its apocalypse. This isn’t Last of Us. There’s no hope for a cure, no prospect of rebuilding civilization. Humans are simply gone. Life goes on, for the birds and the plants, not for humans. Cloud Gardens doesn’t explain this absence; it’s not a narrative game, not in the traditional sense. The stories it tells are the ones players make, the paths traced out by the plants as they climb over the ruins. What stories does a vine leave behind as it creeps across the rusted hulk of a bus?

It’s tempting to interpret Cloud Gardens as a response to ecological crisis, to climate change and all it portends. I tend to agree with Mark Bould when he argues in The Anthropocene Unconscious that in the present, art and culture can’t help but speak to climate change: ecological crisis is so all-encompassing that it enters into every novel, poem, film, song, or videogame, like a specter for which no exorcism has been invented. Which doesn’t mean Cloud Gardens is about climate change, or ecological crisis, or the Anthropocene, or pollution. Its ruins and rubble and the pointed absence of human characters allude to ecological crisis. Yet Cloud Gardens never explicitly draws attention to environmental devastation.

Instead, it invites meditation, peaceful absorption in its voxel landscapes and airy music. It’s an exercise in abandoning the framework of human agency, in chucking out stories in which heroic humans save the day. Everything’s broken. There’s no hope, not if hope means the persistence of civilization, yet life goes on. Time flows. The planet spins in its orbit around the sun.

Cloud Gardens doesn’t have a message. It doesn’t lament the environmental catastrophe wrought by the human species, nor does it preach the gospel of a green new Earth, but it’s still more than a good way to waste away the hours. Cloud Gardens speaks to ecological crisis without speaking about it. It works on players by inviting them to rehearse an activity that’s less about directly manipulating environments than about sparking change in them. When you’re playing the game, you don’t decide the paths traced by the vegetation. You plant a seed and see what happens. Yes, there’s some predictability to how the plants spread across the landscape and, yes, the entire point of placing human artifacts like street signs and shopping carts is to steer the flow of plant life. But still, the player’s agency over the scene is indirect, and this indirection holds a lesson, if not exactly a message: What if instead of grasping things, we let them be? What if instead of making use of the Earth, we let it flourish apart from us?

So much of the ongoing ecological disaster is a product of the human desire to master nature, to transform the planet into resources ripe for exploitation. It’s a desire that capitalism and colonialism intensify, even if they don’t invent it. In Cloud Gardens, however, the player doesn’t perform mastery. Instead, the game invites a more delicate kind of agency – call it nudging, call it letting go. It’s akin to building a trellis for a bougainvillea vine to grow over: you make the conditions, but the rest of the work is up to plant. Or, on a grander scale, it’s like building a habitat corridor: set aside the land for the plants and animals, dedicate yourself to rewilding the planet, hope life flourishes without human intervention. Cloud Gardens offers what so few other games even acknowledge: gentleness, humility, grace.