Companionship and Emptiness in Fumito Ueda’s Games

There’s a curse that hangs over contemporary gaming. In the world of AAA titles, whichever way you look you’ll find an open world game with a map that’s littered with things to do. Side quests, missions, challenges, whatever they might be, they can frequently be busywork to bump up the potential playtime of a game. Even more narrative focused games like The Last of Us Part 2 and God of War (2018) have a plethora of treasures to be found. The former at least does some worldbuilding with its collectibles. But that’s all they are, nonetheless, little motivators to get those trophies, those coveted platinums. And achievement hunting is a completely valid way of approaching games! But it denies games a particular feeling: emptiness. A feeling that throughout his whole career, that Fumito Ueda has captured incredibly well.

Ueda has had a long-standing career, starting as an animator on Star Zero for the Sega Saturn, eventually leading to his work on the seminal titles Ico, Shadow of the Colossus, and after a long development period, The Last Guardian. At the time of each games’ respective release–and even now–they stand as works unlike most other games.

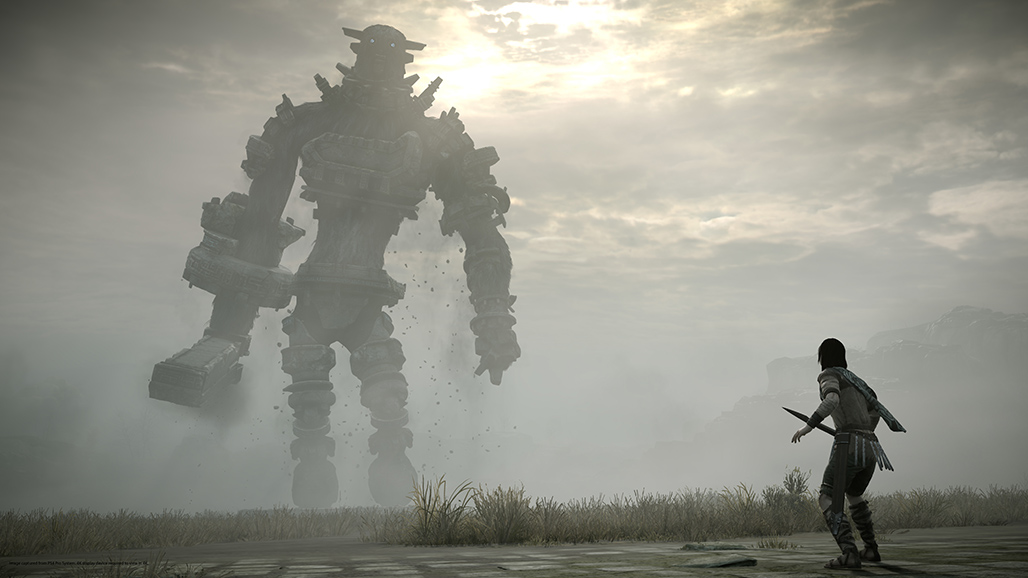

They didn’t have much interest in going along with trends at the time. Ico was an entire game’s worth of an escort mission, a trope in games notorious for its tediousness. Shadow of the Colossus featured an open world with very little filling it. The Last Guardian could also be argued to be an escort mission, only this time with a hulking beast called Trico as your companion, and one that you had sometimes little control over. Each game almost has an amount of player hostility to it. None of them cater to the player’s needs in a way many modern games do; the stories of each are somewhat bare bones, leaving the player to decide many things for themselves, but they all clearly have worlds (or world, depending on your own theories) that have a rich and detailed history to them.

The pseudo-trilogy barely hints at any of the history they all have. A commonality across them are these ancient, sometimes monolithic structures, with implications that they have long since been abandoned. They are impressive, and if they were real would have confounded people as to how they possibly could have been built. But in the moments the player inhabits them as the various protagonists, they are empty. Not in a completely literal sense: in Ico there are the shadowy creatures, and Yorda herself, in SotC there is life in the form of birds and lizards and trees, and in TLG, there are even other creatures like Trico. What I mean by empty, is that there’s only a hint of a culture that once walked those lands and fortresses. The protagonists only ever have one companion to join them in their journey. These places are so incredibly lonely, they feel like they’ve been purposefully forgotten by the world. Each title does feature groups of humans, but they never live in any of the locales we the player get to explore. In fact they outright avoid them, often seemingly for superstitious reasons.

The feeling of knowing somewhere was once occupied with life but now lies void is a complex one. Where I grew up, there was an old abandoned radar station on the top of some hills looking over the seaside. I would go there semi-regularly with friends, because when you live in a place with little to do, exploring abandoned buildings is a good, and sometimes the only, way to spend your time. Parts of the building didn’t have flooring anymore, so the only way to get into certain rooms was by clinging onto the walls and swinging round through the doorways. We would goof around in this place, but it always felt a little sad. This building once had a purpose, and had people occupying it, living their lives, doing their job. There wasn’t any remnant of anything existing there other than the building itself. We didn’t own that space, but we filled it in while we were there. I get that same feeling when I play any of Ueda’s games. The trio of game worlds no longer fill the exact purpose they might once have done, but they persevere nonetheless. Abandoned and empty though they may be, like the radar station I would visit with my friends, it’s through companionship that the protagonists fill these spaces.

Ueda clearly has a strong sense of scale, the strongest evidence for this being the titular colossi, and their colossal size. Even with these massive creatures and buildings, it’s through the relationships you get to develop that these spaces are really made to feel whole. The titular Ico can’t even understand Yorda, yet right from the offset he is determined to help her. This of course encourages the player to do the same, you aren’t just there to guide Ico out of this prison, you’re there to help his new friend too. That theme of being unable to communicate translates across both of Ueda’s other titles too. Wander can’t converse with his steed Agro, and the unnamed boy is in a similar position with Trico. Yet in each of the games, you come to rely upon your companions. They do things you can’t do, and look after you when you might need care most, which makes the world feel a little bit less intimidating.

Many modern titles are exactly that, intimidating. The sheer cliff face that is a contemporary AAA game map dotted with endless objectives and quest markers is a daunting one. Ueda’s games reject that in many ways, not just by simply not having anything like that, but by pairing you up with another living being just so you don’t have to face things on your own. The games don’t really tell you about the history of the world, there is no exploration in lore. Doing that would fill them with too much noise. The feeling of emptiness is critical to the games, as it encourages the player to bond with their companions. The games don’t exactly give you much choice in any case as they are all linear titles, but even so, if these spaces were filled with lore, they would be a distraction from the companions you’re spending time with. The worlds are interesting because you can speculate what might have been, but the games shine most with the relationships that are in them. I don’t want to be distracted by a cutscene going into lengthy detail over what it all means–what I want is to pet Trico or Agro, or to hold Yorda’s hand. Even though the linearity could arguably force you into bonding with the characters, it’s through those simple actions that you really are able to. Now with Twitter accounts like Can You Pet The Dog? it’s more and more common to find interactions like that –non-violent, pointless ones– but for the first two Team Ico/ gen DESIGN games it wouldn’t have been commonplace compared to other titles released at the time.

Games like these are incredibly hard to pull off. They can be hard to revisit because of the limitations of both outdated game design as well as hardware. But even still these games stick with me. They’re sad in a variety of ways, but never feel lonely in them for too long. I always have someone to accompany me, and the moments in each game where you are left alone it’s that much more painful. And this is done without huge swathes of dialogue, or text to read, or reems of exposition. These worlds are huge, and you are small, but you can be small together (although maybe not that small in Trico’s case).