Provided by author

Condemned: Criminal Origins and Non-Places

There’s a location in Condemned: Criminal Origins that always sticks in my brain as the game’s eeriest and most memorable: Bart’s Department Store, the star of the game’s fifth chapter. Like every location in the game, it’s been completely abandoned; the tattered Christmas decorations that still hang in every section of the building give a hint to when. It’s the scariest level in the game by far, and a perfect microcosm of everything that’s incredible and unique about Condemned.

There’s just something… off about the entire presentation of Condemned, from the setting to its enemies and even the feel of the combat. There’s a deep feeling of discomfort and unease that permeates everything you do in the game, one that seems wholly unique to it. There are plenty of horror games I’d call scarier, but none of them scare me in the same way. In the department store, this comes to a peak—everyone remembers the department store.

Condemned follows Ethan Thomas, an FBI agent framed for murder by a vicious serial killer. Desperate to clear his name, he’s forced to explore condemned and derelict locations across the city in order to catch the murderer and clear his name. The story is pretty weak, and often stifles the oppressive mood, particularly when later plot beats start providing supernatural answers to the game’s most frightening mysteries. None of this is really important to the effectiveness of the game’s atmosphere, except in one critical way: how it guides you through places that aren’t really places at all.

As the title suggests, Condemned is set almost exclusively in environments that have been shuttered off from regular society. You spend time in a crumbling office complex, a drained swimming pool, and plenty of other locations abandoned by the rest of the city. The department store is one such area, caked in grime and covered in peeling wallpaper. It’s probably where the game’s core sense of dread will start to set in; you’ve spent the last few areas traversing faceless metro tunnels, filled with colorful ads that suggested some kind of pulse from the city above. Now the environment’s changed, but the encroaching sense of separation from the rest of the city has followed you right up to the surface.

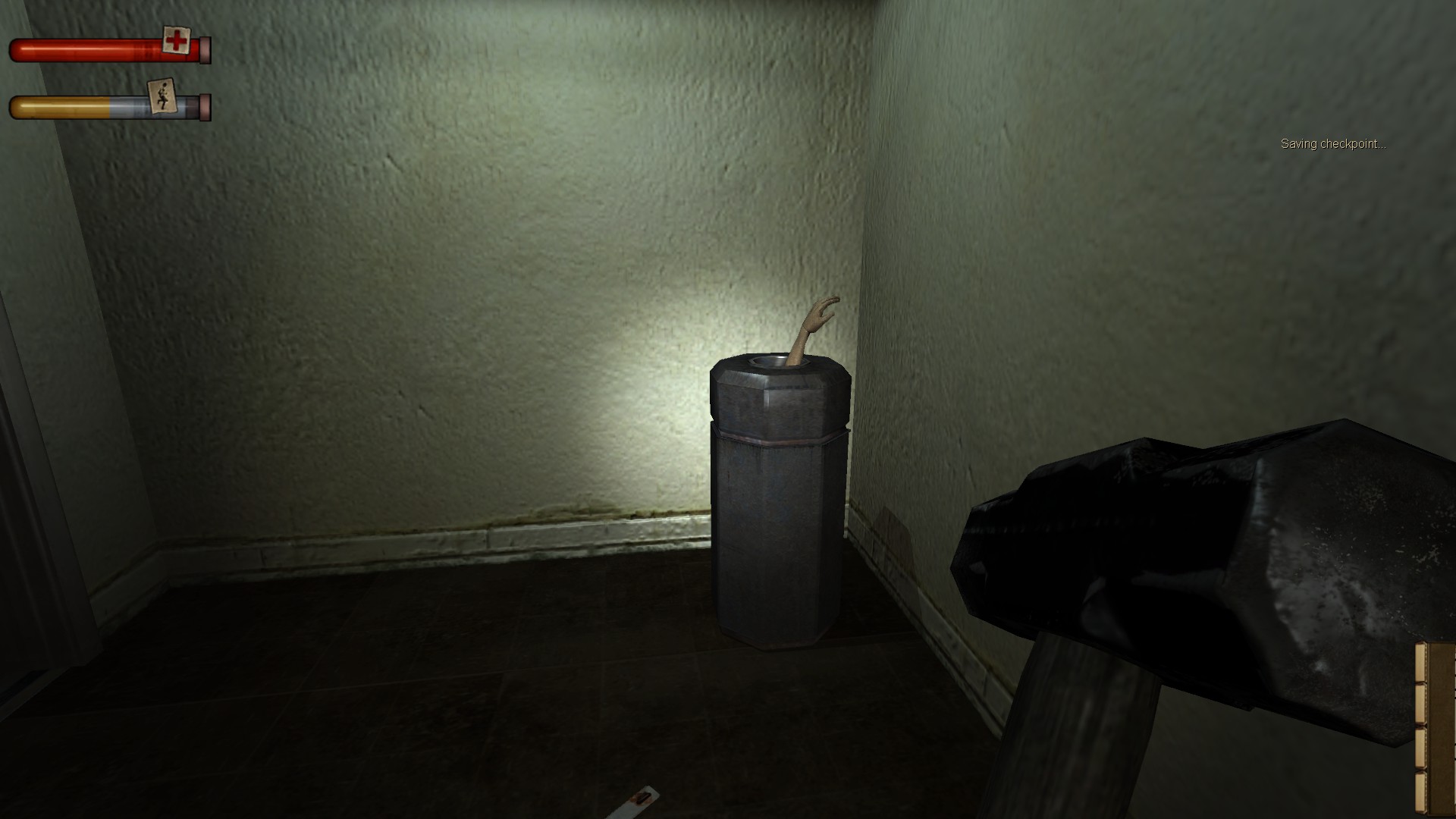

The department store is far past being a dying thing—if it’s decomposing, it’s reached skeletonization, baring its bones to any would-be scavengers or lost souls. Everything that was worth anything is long gone, and what’s left only serves to advertise the bits of soft flesh that aren’t on the corpse anymore: empty racks and naked mannequins. It’s a kind of fully-featured emptiness that’s actually quite rare in a lot of games, even when they go for a similar aesthetic. Fallout is filled with places like this, but typically has to rationalize their existence by offering some kind of intrinsic reward for exploring them. In Condemned, the only collectibles you can find in the department store are bird corpses and bits of rusty metal, reinforcing the ever-present decay.

The struggle with talking about death in relation to a department store is that death comes from life. A rotting building can be easily likened to a corpse, but that implies that the building used to be animate. And while something like an abandoned house certainly might echo the memories it helped create, a store is just… a store. Sure, there’s always foot traffic to keep a store “alive” (a mall only becomes a dead mall when people stop going there), but that’s only life in the medical sense, with blood pumping and oxygen circulating. Just how full of life and personality is a chain department store like Sears? Sears can die (and is currently doing just that), but can it ever be alive?

Marc Augé discusses the non-place in his book Non-places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity. The anthropological concept of a non-place flexibly refers to the idea of a place that does not exist in the state of a traditional place: where socialization, reflection, or living occurs. You do not, for instance, typically visit a shopping center to meet people or think or linger for any longer than necessary. Nobody lives in Walmart, and anyone that leaves their mark on one has either vandalized the store or made a mess. As a result, non-places become transient places, where people are anonymous and little is left to mark their presence.

They are places where, from the moment you enter to the moment you leave, you’re just another face in the crowd. Non-places erase the individual human, sometimes to streamline the function of the place, and sometimes out of pure happenstance. They are department stores, subway stations, and city streets. They are, in short, the entire world of Condemned.

It’s a truly empty place, as vacant as death. But in horror, the dead have a habit of coming back to life. In order to discuss the non-place, we need to discuss its inhabitants.

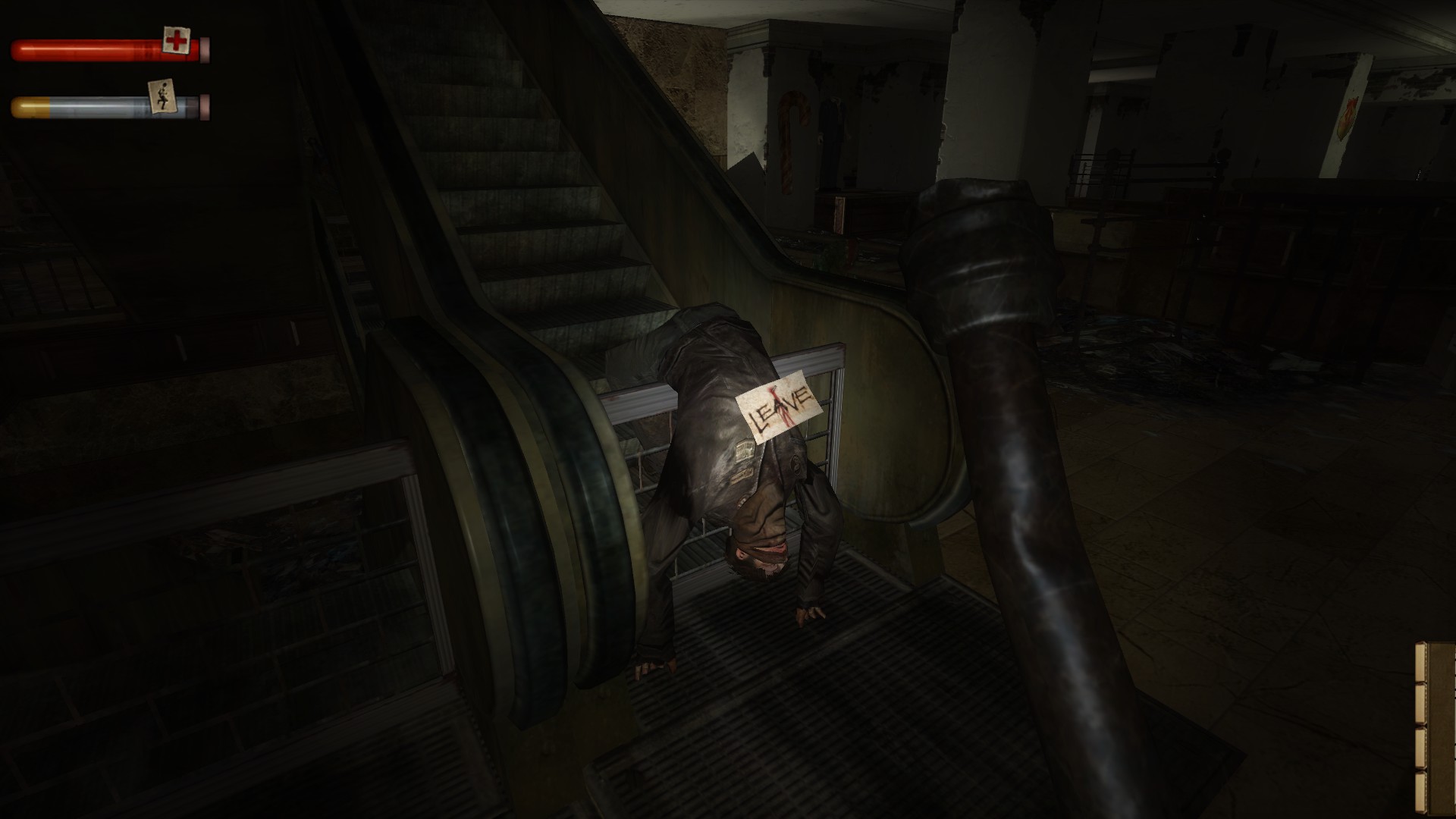

As you walk around the desiccated mannequins and looted displays, a corpse comes tumbling down an escalator. To it, a bloody note has been pinned: “LEAVE.” It’s the first and only warning you’ll get. Before you encounter any of the building’s new occupants, you hear them shuffling around, sometimes just around the corner. You’re isolated in Condemned, but you’re far from alone.

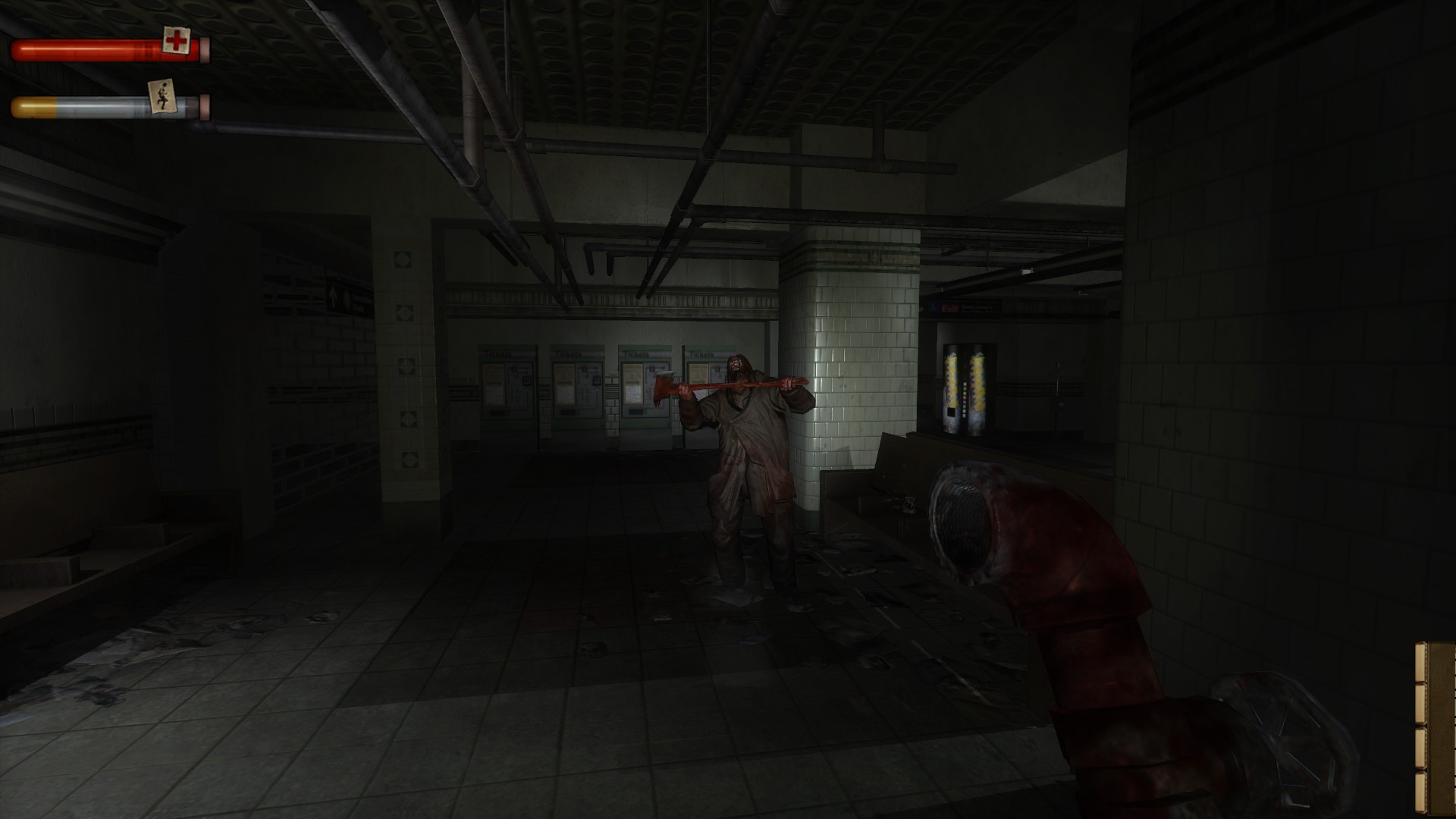

Condemned’s enemies are the hellish equivalent of those faceless goons that block your progress in arcade fighting games. They’re all ostensibly the city’s disadvantaged, driven completely insane by a mysterious force that’s made them impossibly, suicidally enraged. Enemies mostly use improvised weapons, like loose pipes ripped off the walls or two-by-fours littered on the ground, and will simply never stop attacking everything around them until they’re dead. They exist in impossible numbers, have zero allegiance to each other (they’re routinely seen killing each other and infighting is quite common), and speak entirely in grunts, yelps, and screams.

These attackers fill up the game’s aforementioned non-places, leaving the player perpetually vulnerable to sudden, brutal ambushes. Unlike similar games with melee enemies, they actually have rudimentary tactics beyond just rushing forward, all of which are designed to scare the shit out of you. Their favorite is to run off only to wait around a nearby corner and jump you. They add an incredible amount of tangible horror to the game’s surreal atmosphere, deepening the sense that the world around you is in a state of disarray that’s difficult to grasp.

Condemned is a survival horror game, but a relatively unique one due to the discardable nature of firearms. When guns appear, they’re capable of killing most everything in the game with a single well-placed shot. But they’re stuck with the amount of ammo loaded into them, and can never be reloaded, restricting their function to a powerful but limited protection item.

Instead, the game keeps the pace of combat a lot slower, primarily focusing on melee attacks. Just as enemies rip pipes off the walls and scoop rusty pieces of rebar off the floor, the player is forced to copy their methods to survive, beating attackers to death with whatever is within arm’s reach. Unlike most games focused around melee attacks, Condemned lacks a system for combos or deeper strategy, and the sound design generally lacks any of the typical satisfying flourishes to denote hits or kills. In their place are the simple sounds of hard, blunt objects impacting flesh. Even the finishing moves, which range from snapping necks to ramming enemies into floors, feel less like cool fatalities and more like violent outbursts. It’s brutal, simplistic combat, lacking many of the standard notions of what makes a typical brawler satisfying. It’s like someone took the vibes-based combat in a good Silent Hill game and made it about hitting people in the face.

The non-places in Condemned are given a new, brutal undeath, one that serves a cyclical purpose. With the aforementioned rarity of guns, most of the game’s slaughter is hands-on by necessity. You rip pipes and scaffolding off the walls just to stay alive, hastening the deterioration of the game’s setting, stripping its character away with your own hands—clawing away at the city’s innards. The game’s combat is uncomfortable, like the experience of spending an extended amount of time in a department store. It’s just a bit too close and a bit too visceral to be entirely entertaining when you hit a guy until he stops moving.

In Condemned, the non-place twists in on itself, creating places that erase the self and streamline brutality. These places were once safe, but it would be a mistake to think that they were ever comforting. They existed to serve a function before their function was deemed useless or unprofitable, and then they were forgotten—left on their own to transform, ultimately into something evil.

Condemned’s levels, which are better understood as non-places, anonymize all of their inhabitants until the entire flow of the game’s combat takes on a surreal quality—impossibly large hordes of enraged killers stalking and attacking you, never showing a single speck of fear or remorse and never standing down even in the face of impending death. Not only is the player forced to become as brutal as the opponents they face, but they aren’t made to feel good for it. When a fight is over and corpses litter the floor, the silence can be overwhelming. You start to think you hear things, and maybe you do.

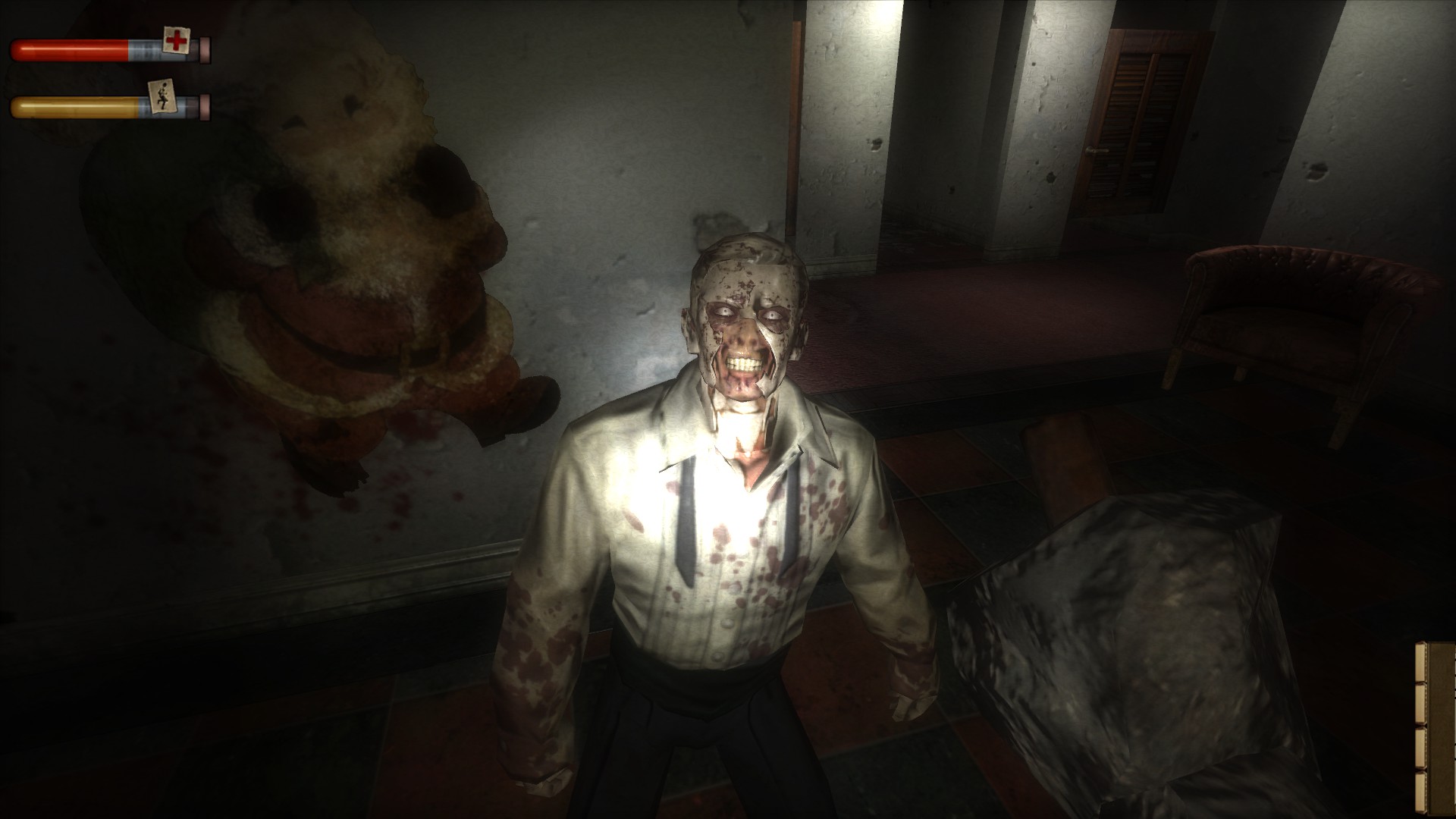

By the midway point of the department store, the player has probably gotten good enough at the combat to ease the tension a bit, so the game introduces a new enemy, one that brings the overarchingly unsettling tone to a fever pitch. It’s the moment in the whole game, and it’s when a department store mannequin suddenly moves off a stand, casually walks over to a two-by-four, picks it up, and starts trying to beat you to death.

This is the moment everyone remembers about Condemned. The mannequin is actually one of the game’s crazed attackers, uncharacteristically disguised and even more uncharacteristically quiet. It’s an absolutely wonderful “oh shit” moment which the environment continually reinforces. There are plenty of other mannequins around the store (expect to nervously remember all of the ones you’ve already walked past), and a few will try to jump you when you aren’t looking. Stranger still are the mannequins that seem to be legitimate, plastic and all, that still seem to move and reorder themselves when out of sight. In the game’s most iconic beat, a group of mannequins reorders itself around you in increasingly threatening ways whenever your back is turned.

You never find out who or what shifted those mannequins around, but whatever it was, it wanted to close you in.

Mannequins are fucking creepy—they’re creepy enough that Shadows of Rose, the recent DLC for Resident Evil 8, has an entire sequence dedicated to them. There’s a reason that near-human figures have been a common scary theme in stories and folklore for a long time. Mannequins have no distinct features or traits, save the vague outline of the body itself; a human visage with none of its character. The subtleties of being human are sucked out and replaced with something hollow. In the light, it’s easier to see a mannequin for what it is. Turn the lights off, and suddenly the distinction between person and person-shaped is blurred. If I know I’m going to walk by a shop window displaying mannequins in the dark, I cross the road.

An object like a mannequin is inseparable from a non-place—what else can be said to live in a department store? They’re as formless and hollow as the spaces they inhabit. But as you beat away at the disguised mannequins in Condemned, you find they aren’t hollow. Hit them hard enough and the plaster encasing their skin peels off, revealing the broken, bloodied human underneath. It’s a bit like poking open a cocoon and watching a liquefied caterpillar ooze out. The non-place in Condemned facilitates a sort of ongoing transformation, one that flattens and paves over what it means to be human. If the department store is a corpse, it’s a hungry one.

Everything and everywhere in the setting of Condemned has been absorbed into this collective digestion, becoming as devoid of form as a mannequin. Society’s disadvantaged become faceless goons, abandoned buildings have rotted away and shed their facades of comfort, and even the player is forced to replicate the same callous, brutal cruelty as their attackers, holding on to only a thin veneer of distinction keeping them apart from the assailant trying to beat them to death with a rusty pipe. This is a game where everything is disposable, from places to people.

But like non-places themselves, the game never allows you to take comfort. You’re stripped of dignity and character just like everyone else. You’re a husk trapped in a non-place, twisting deeper until you’re just a part of the scenery, losing what little distinction you had from the places you inhabit. You’re another lost soul, trapped in a freefall, desperately trying to claw your way out and only sinking deeper into the quicksand in the process.

The world of Condemned feels so uniquely unsettling because it confronts you with the vacant malice of decay in all its forms, from structural to societal. It absorbs you into a city that’s dead and decaying—one that’s maybe never been alive at all—and casts you as the maggot. Try to muscle out, break free, it doesn’t matter. You’re a parasite and here’s your corpse.

The end of the department store has one final surprise. As red and blue lights flash through the boarded-up windows, it’s clear that the police have caught up with you. My mind flashed back to other games with similar action sequences, like something from Max Payne or Grand Theft Auto—those games make you want to run away, but I wanted to be caught. I wanted the police to storm in and take me away from all this. I wanted to get out.

No such action sequence occurs. The game compels you to run away, but no cops give chase. Nothing much really happens, as though there’s another dimension between you and the police cars outside; maybe, for all intents and purposes, there is. It’s the perfect, surreal end to one of the most unsettling areas in a horror game. More importantly, it’s everything I love about Condemned in a single, indescribably eerie moment.

Instead of getting away, you fall into a hole, deeper into the brutalizing world of Condemned. It doesn’t let you escape your fate. Non-places take something from you, and nobody ever said they had to give it back.

If you like what we do here at Uppercut, consider supporting us on Patreon. Supporters at the $5+ tiers get access to written content early.

1 thought on “Condemned: Criminal Origins and Non-Places”