Provided by Hidden Fields

Desperation in Translation: Mundaun and Devotion

Horror is tricky in translation. Symbols that may be recognized within one culture may require explanation and context to another, and that kind of thing can quickly veer into over explanation. Pacing, so crucial to building dread or causing sudden shocks, is easily broken. Weighted phrases in dialogue may go over players’ heads and visual imagery or icons may be inscrutable. But two of my favorite games in 2021 delivered dread and terror by being thoroughly and essentially saturated in the culture and mythologies of their creators. Both Devotion and Mundaun slowly unspool their stories, providing just enough context along the way. It’s as if their stories share the same rootstock, with their above-ground branches and vines being uniquely adapted to different places and times.

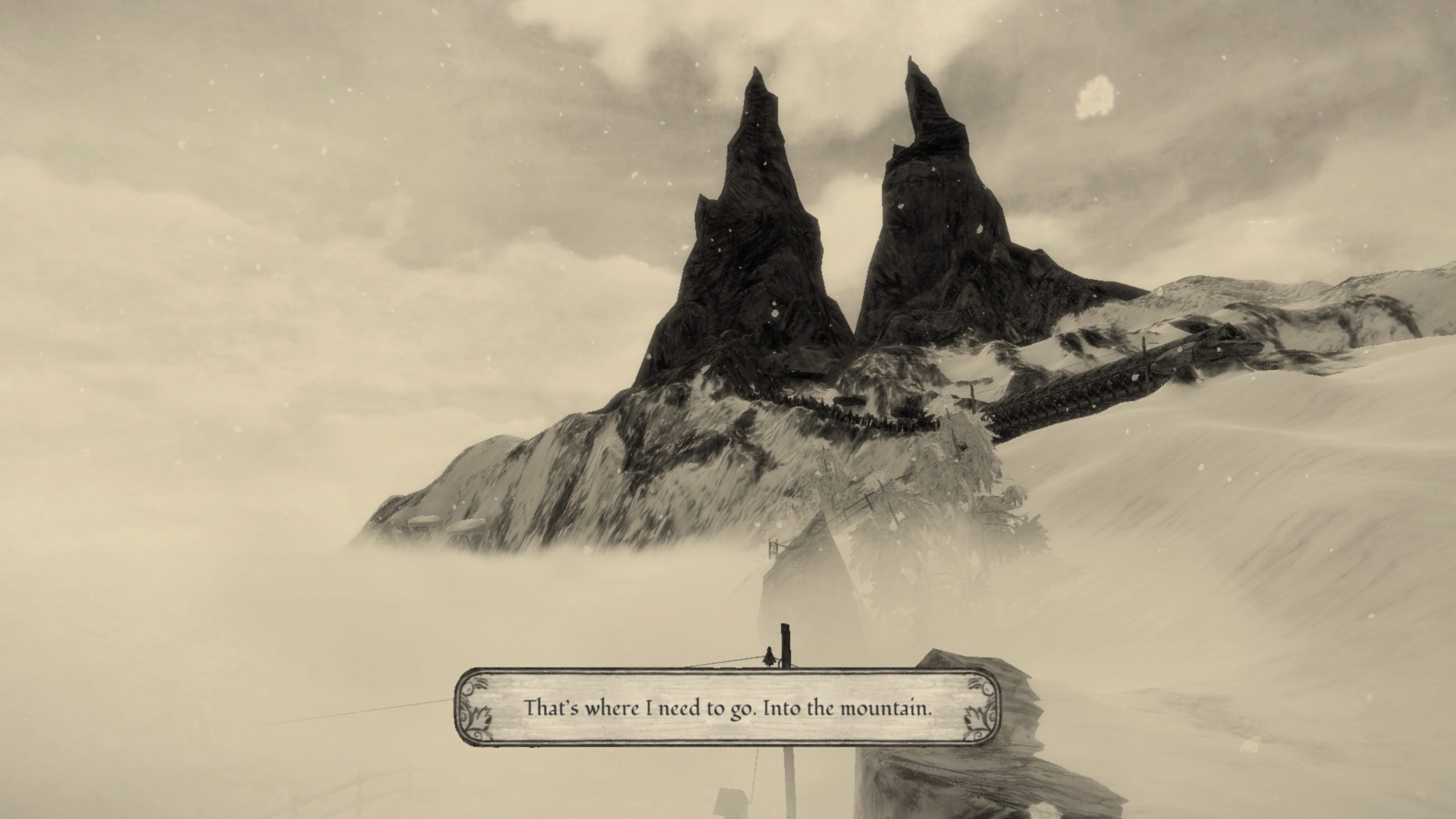

Both games could be categorized as folk horror. Or maybe that term isn’t quite right– both have great cultural specificity and are tied completely to a time, place, and people. For Devotion, Red Candle Games provides snapshots of different cultural pressures on the family in ‘80s Taiwan. For Mundaun, Hidden Fields brings players to alpine Switzerland, complete with isolated farmhouses, a rickety truck, and an ancient presence that lives under the mountain peak. Both games pull off the feat of bringing players into the symbolism and folklore of their creators’ background and imaginations. In doing so, everything is heightened, from the dreadful deals of Mundaun to the hallucinogenic terror of Devotion‘s religious cult.

Another aspect both games share is a protagonist who begins the story with rich and powerful relationships with other characters. For whatever reason, this is a rarity in games. They’re both about family, and our main characters find themselves hopelessly entangled in dark secrets from the start.

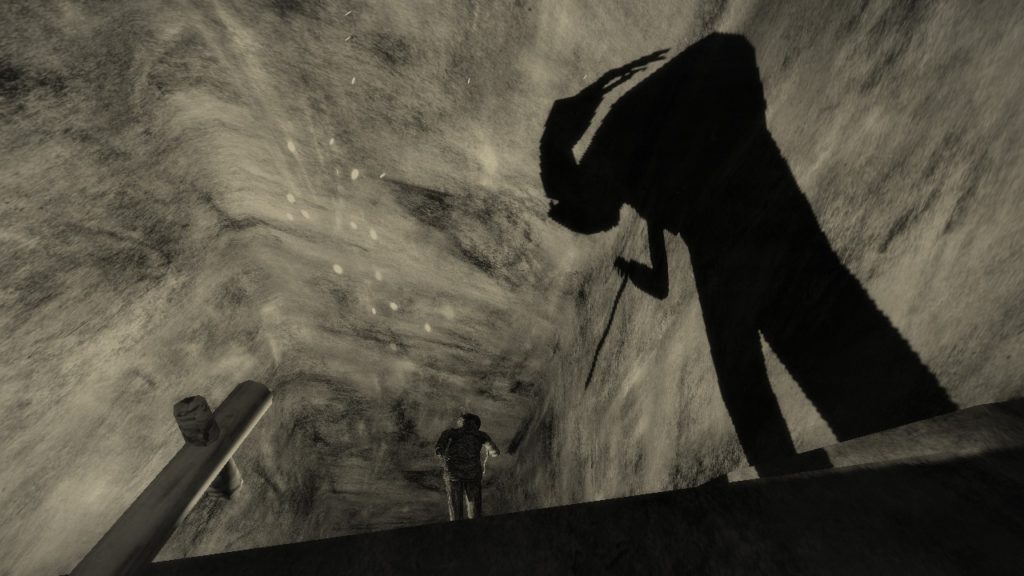

In Mundaun, you play a grandson. The game begins on a nearly empty bus that winds its way up into the mountains, taking the character back to a place they visited regularly as a child. A letter from the local priest informs you that your grandfather had died, had been buried, and tells you not to bother coming. But you do so anyway, only to find that everyone involved has been hiding a troublesome past.

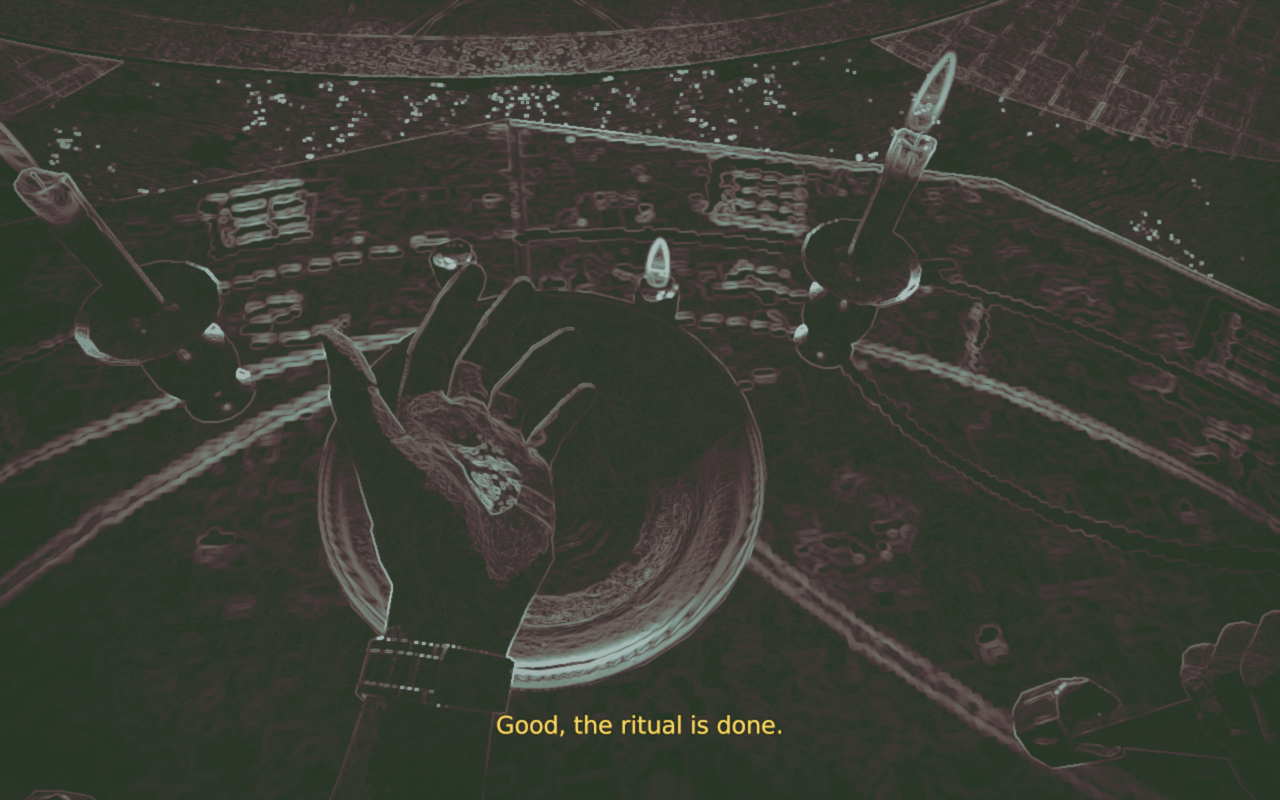

In Devotion, you play a father. The game begins with your family, with your mother and daughter in an urban apartment. Things become fragmented. Things have gone wrong in the early years of the 1980s, as your daughter became increasingly ill. Doctors seemed useless, so your neighbors advised you to turn to religion and ritual. Unlike Mundaun, it’s not your grandfather who embraces old secrets to save his home: it’s you. Or, rather, that’s the question of both games– is the story that someone struggled against the odds, even in the face of others’ fear and disbelief? Or is the story about being, yourself, in the grip of fear and mania?

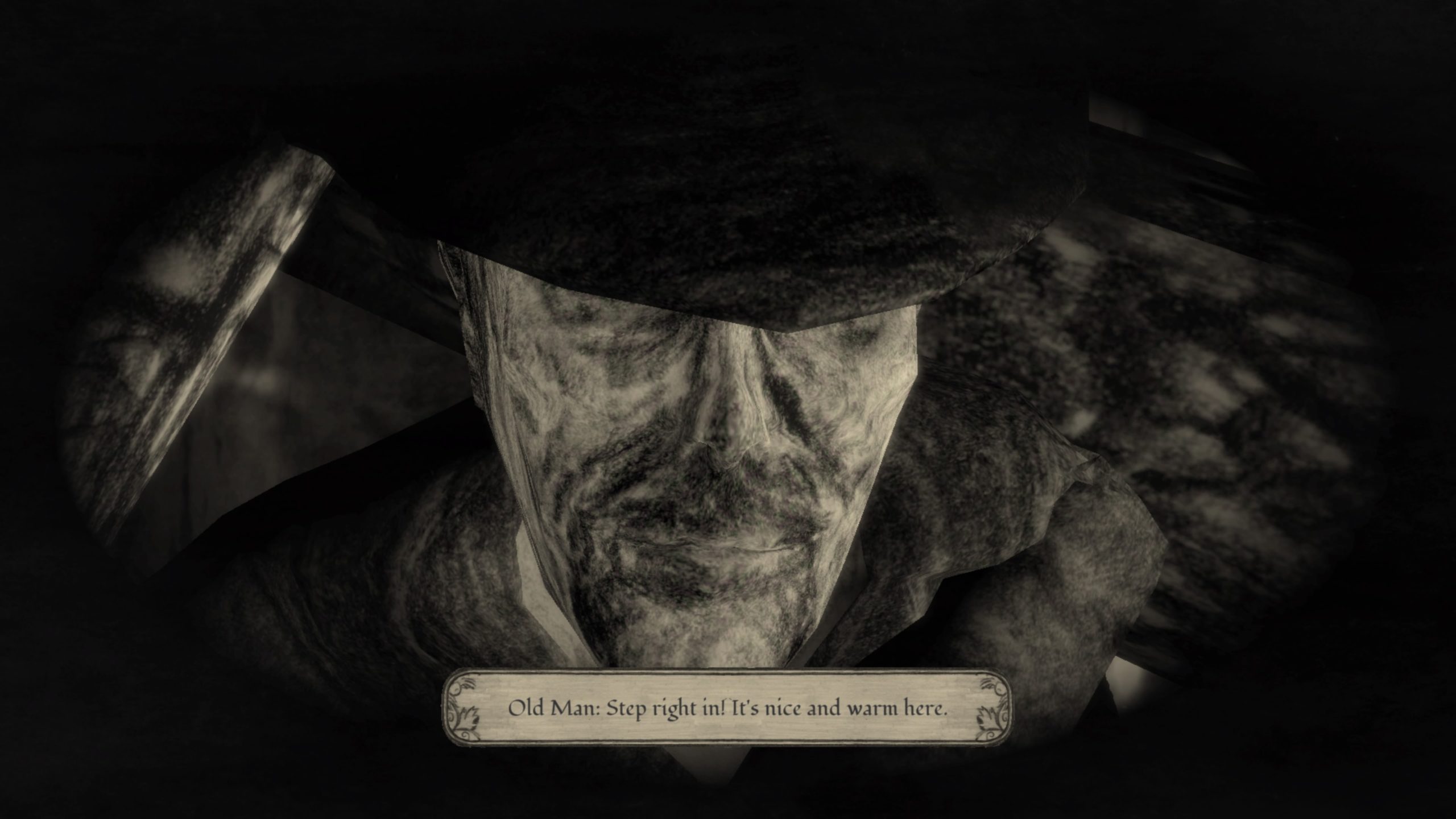

Both games tell stories of desperation. The grandfather in Mundaun, together with the others who become the mountain’s elders, were faced with an oncoming battalion of soldiers invading over the mountain peak. At this crucial moment, an old man appeared, promising them a miracle in exchange for an unspoiled soul. As the player, you inhabit these scenes as an outsider, sometimes a non-present entity in a memory, sometimes as a participant misplaced in time. If players care to look, the old man of the mountain has a face that constantly shifts, with pencil-drawn features melting and flickering under his hat. The place of Mundaun is a real one, as real as the Romansh-language voice acting and signage. The old man of the mountain might be just as particular to the place, but he is recognizable to me, nonetheless. Never trust the man who walks into the scene just when circumstances are at their most dire.

The monster in Devotion is more obscure. Its story is told by moving between the same apartment, each separated by the passage of years. Initially, everything is celebratory. The father is a successful writer, the mother a famous singer, and their daughter aspires to similar stardom. As that deteriorates, so does the apartment, which increasingly becomes more of a shrine or hoard that surrounds the daughter’s room as the father seeks divine intervention. As he goes deeper into cult ritual, the material trappings of it increasingly saturate the family home. His inward and outward realities increasingly match one another. He isn’t an unreliable narrator so much as one whose perspective is increasingly, and monstrously, warped and transformed.

These are the kinds of stories that video games are good at telling. They’re both examples of why I love horror games, in particular. Game worlds, which are often designed to open up to players in reliable and understandable ways, can be manipulated by horror designers into unstable realities that play with players’ expectations. Roads in Mundaun may turn ninety-degrees into bottomless tunnels and the hallways between apartments in Devotion can elongate into labyrinths. Horror bends and sometimes shatters reality.

That’s made even better if that reality is thoroughly established. All the cultural details in Devotion and Mundaun help to accomplish that. For all of the spatial and temporal distortion involved in both games, they remain grounded in the realities of their designers. This goes all the way up to the mythological figures of the man under the mountain and Cigu Guanyin. I’m always up for stories that only their authors could tell. Right now, some of the best stories like that are being told in video games. I can’t wait to see where I go next to go out of my mind in 2022.