Screenshot taken by author

Fallow: The Comfort of Depression

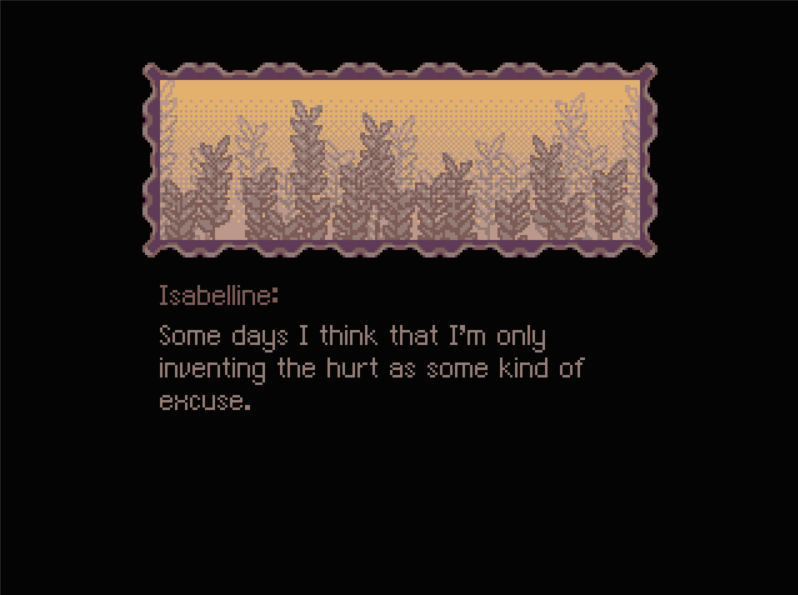

I wonder, occasionally, how much of a role I have played in my own suffering. Obviously, it’s an intrusive thought, an irrational way to make sense of the many cruelties of life. But, seldom, it’s an irrepressible notion, almost intoxicating. It’s bizarrely easy to wallow in the search for comfort– I slot in just fine to a depressive episode, and once I’m there, it’s easy to stay within those four walls. This comfort is just as much a lie as blind optimism. It’s a tool I use to avoid the systemic issues around me, the grand cosmic problems in our world that boggle the mind to consider. It’s been a profound year of global illness– so much that it rings cliche to mention. But it must be said to approach the specific exhaustion that permeates Fallow.

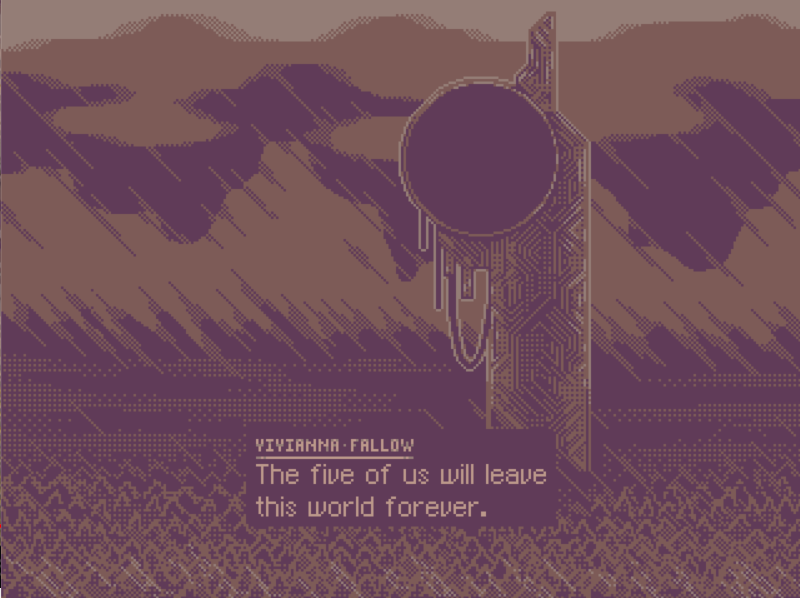

Ada Rook’s Fallow is a game about escape, or maybe the inability to run away. Isabelline took her last name, Fallow, after leaving the city to live with a group of girls she would come to know as her sisters. Her robotic urban life from before was suffocating her– she was mixed unfavorably in a world of machines that she could not understand, nor did she possess any curiosity of them. After living a life of quietude in the countryside for some time, her sisters begin slowly disappearing, along with nearly every trace of their existence. Soon, Isabelline is the only one that remains. Despite her cavernous loneliness, she chooses to stay in their empty farmhouse instead of returning to the city.

In a dying world, nowhere can accommodate you. Not fully. City life drains us of our identity, moving quickly to a more rapid entropy. The paranoia of walking in streets full of strangers, devoid of any community, rings in the back of our heads. The myth of country living,”cottagecore” and the bucolic, is a fantasy– a placebo of a medicine that fails to cure the psychic sickness that plagues us. I gave into this urge this year, too. After working in the city for little pay for most of the year, I felt that urge to flee. I took a week off and brought just a few books and some DVDs to my mom’s house in rural Georgia. The farmland of my hometown seems to echo the gothic landscape of Fallow, the blend of wheat-beige and faded grey-lavender. Mostly, I sat in the dark in my sister’s room. I don’t have my own bed there. Despite manufacturing some sort of healing journey in my head, I did almost nothing. I thought very little about anything at all.

My trip was awkwardly sandwiched between my playing of Fallow, which I played soon after I returned, and my first viewing of Todd Haynes’ Safe. In Safe, a wealthy ‘80s housewife named Carol (played by Julianne Moore) begins having allergic reactions to the environment around her. Though some people in her life suspect her allergies are psychosomatic, the very real consequences of her attacks lead her to a commune in New Mexico of people with similar complications, autoimmune diseases, acute anxiety. She moves here and begins to think her condition will never improve, that she’ll never return to her old life. More than her allergies, what seems to afflict Carol is her pervasive lack of purpose. She stumbles her way through a speech about the rights of the disenfranchised, her first attempt at crystallizing a thought of her own in years. It would have been easier to not say anything at all.

Though empty, Carol serves as a cipher for the queerness of modern life. There is nowhere she belongs. No physical location makes her feel better, more full, happier. The world is slowly tilting towards a point of no return– the very ‘80s, almost new age-y obsession with “pollutants” gave way to the climate crisis of today. The nature of Carol’s self-hatred goes mostly unexamined, externalized to the world around them. Isabelline’s plight seems much the same.

There’s a few puzzles that keep Fallow buoyant. They distract from Isabelline’s aimless wandering. Since her sisters’ disappearances, she’s taken to sleepwalking. Every day she awakes in a new place and makes the long trek down a highway back to their rickety abandoned house, which seems just slightly different from how she remembers it. Her dreams imply a grander plan for her, for her sisters, but it’s hard to say what is reality and what is a constructed fiction made to cope with her dereliction. She has visions of the dynons, great world-eating worms of lore, dead and decaying in barren acres. She feels an odd connection to them and their husked bodies, which hide many mechanical secrets within. Isabelline tours the skids, underground fonts of electric energy, in search of answers, but finds mostly nothing.

By the end of Fallow, Isabelline is left as purposeless as she began. Though her depression slowly melts and gives way to hope for something better, for a plan to free her from her loneliness, she is left with both feet firmly planted on the ground. The world does not end. Her sisters do not reunite with her. Neither the worst nor the best outcome comes to pass.

This year has mostly felt the same—deeply static. Nothing has changed. The world, somehow, feels demystified. Almost mundane. I’m still learning to live with that.