Feat of Klei: How Griftlands Exemplifies a Nurturing Approach to Game Development

These days, Klei Entertainment’s games are defined as much by their roguelike structures as they are by their signature sharp comic book art style. Following the success of the Vancouver-based studio’s 2012 stealth action title Mark of the Ninja, releases such as Don’t Starve, Invisible Inc. and Oxygen Not Included have leaned heavily into intricately stacked rule sets and procedural design. But what seems like a deliberate shift in focus may be quite the opposite – the organic result of a more open, unstressed approach to development.

“I don’t think we’ve ever written out a coherent Klei design philosophy,” said Kevin Forbes, programmer and designer of Klei’s current project, Griftlands. “But we do have some touchstones that we’ve picked up through experience that we keep applying.”

One of those touchstones is the sense of visual and mechanical reliability. “Clarity is super important, especially if you’re asking players to make informed mechanical decisions,” Forbes said. “That doesn’t always mean giving full information, but it at least means being consistent with your action outcomes, and showing the player the reason something happened after the fact. The last few games that I’ve worked on at Klei (Don’t Starve, Invisible Inc., Griftlands) are systems-heavy and borrow a lot of inspiration from roguelikes, so they all lend themselves to this kind of embedded tutorializing and discrete decision making.”

Forbes explained that Klei’s development methods “tend to be very iterative and exploratory.” It’s a phrase that explains this logical sense of purpose in their games, but also hints at a desire for innovation.

Indeed, Klei’s games are as varied as they are consistent. Whereas many small studios become known for a specific series or genre, Klei constantly switches play styles, from Mark of the Ninja to the turn-based strategy of Invisible Inc. to resource management in Oxygen Not Included. This is something Forbes values. “I personally love jumping between genres,” he said. “Taking on a genre of game that you’ve never built before is a great way to grow as a designer, and even to bring fresh ideas to the genre itself. I don’t think I’d enjoy working on the same type of game for a decade or more.”

He has a similar attitude to sequels. “If you keep things too similar, you run the risk of boring your players (and yourself). If you get too experimental, you risk alienating the players who loved the original game,” he explained. “So the price you pay for stability is you’re working with creative handcuffs on. I usually gravitate towards working in a new genre, because after spending a couple of years thinking about the same types of problems you just naturally want to try something fresh.”

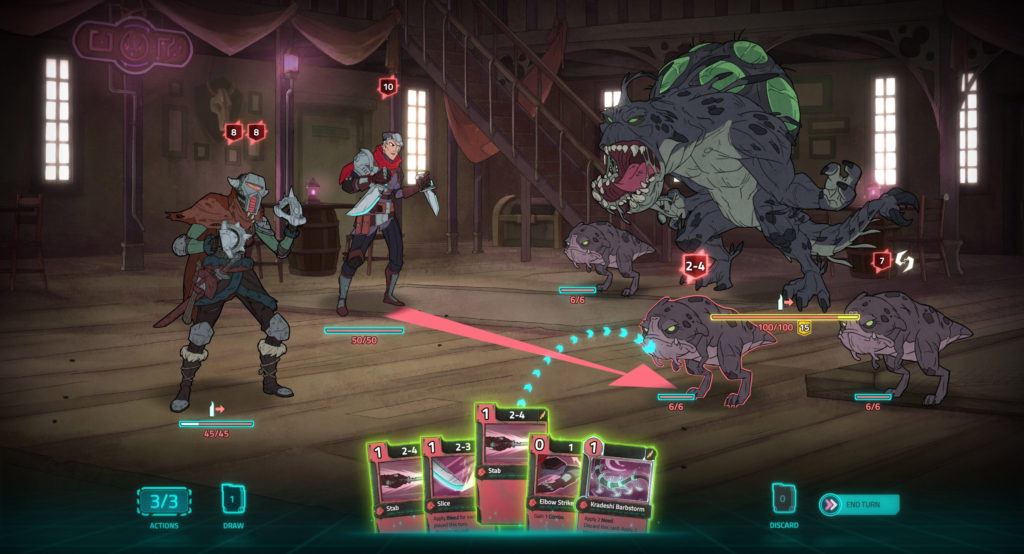

This thinking has spread to Griftlands, where the something fresh is its amalgamation of RPG and deck-building. The core idea motivating this sci-fi bounty-hunting adventure is that how you talk to and negotiate with NPCs should be as crucial as your combat prowess, so an activity like arguing over the fine points of an employment contract has to feel as compelling as a deadly shootout. Griftlands deals with this potential disparity through its cards. As with the likes of Slay the Spire, you’ll face off against an opponent and strategically choose which cards to play from your randomly ordered pile. Except here the choices sometimes represent your attempts to haggle and persuade, by balancing attributes such as composure, influence, dominance and impatience.

It’s a system that creates a sense of organic deal-making, as you judge when best to step up the aggression or adopt a conciliatory tone. But of course it’s all abstraction, which works by translating unpredictable psychological traits into numerical formulas. It’s the kind of calculated clarity that makes Griftlands feel very much “on brand” for Klei, with its layers of transparent rule sets that turn human behaviour into a series of fascinating puzzles.

But the development of these elements also epitomizes how Klei not only encourages new ideas, but allows designers space and time to test them out, even to take directions that don’t prove fruitful in some cases. While the first trailer for Griftlands (which debuted at E3 in 2017) certainly outlines the concept of an RPG that enables players to approach situations cerebrally as well as physically, it doesn’t contain a single card, because the systems in place back then were very different.

“The game used to be a lot more traditional,” Forbes explained. “With turn-based, menu-driven combat, dice-roll skill checks in conversation, craftable gear and character leveling. With the addition of deck-building, most of that ended up being superfluous, and was removed.”

It wasn’t only the familiar RPG elements that were taken out. “The weirdest thing that got cut was a real-time schedule and economy,” he continued. “Buildings on the map used to create goods based on their staffing levels, and you could actually sit back and watch deliveries come and go, and even rob them if you wanted to, which would (sort of) affect the price of whatever was downstream. It was a fun thing to build, but it was never actually any fun to play in the context of a game where you have to walk around doing quests with a small party.”

It sounds like a costly sacrifice, even if some of these ideas could be salvaged for future projects, but it’s an acceptable part of the process for Forbes. “One of the most important things when designing a game is to learn when to cut a part that isn’t working with the whole, even if you personally like it,” he said.

So why were cards and deck-building the right solution? “Our original conversation challenges were based on spending resources to influence random rolls,” Forbes explained. “But in execution it was a lot less fun than fighting. We started looking for ways to make the process of negotiating more engaging, and found that card game mechanics were a really good fit. Cards present the player with a limited, randomized subset of their total available actions at a given time. The player has some control over how these actions come up (through deck building and cards that draw more cards), but they always need to be hedging their bets and making the best of any given situation.”

Playing Griftlands today, the cards obviously streamline the different ways of interacting with NPCs, including combat, into a single coherent logic. Lots of psychological strategies now appear as quantifiable choices. “Say you want to improve your relationship with someone who you need to negotiate a trade deal with,” Forbes said. “You might find them in a bar, in which case you can spend some of your money to buy them a drink, which will make them like you a little more, which will make your negotiation easier by reducing the target resolve score. But they may insist upon you drinking with them, which will insert Tipsy status cards into your combat deck. Refusing the drink may force you into a harder negotiation, but if you show up to the boss fight with a deck full of tipsy you might regret it!”

Another reason that Griftlands and Klei’s other recent games tend towards logical rule sets and roguelike structures may be the relationship between the company and its community of players. Griftlands has been available in alpha since last July, and has just now been released in early access. This practice has become typical for Klei, as they get their games into players’ hands as soon as possible, relying on user feedback to aid the incremental process of exploring and tinkering. From this perspective, it makes sense to create games that focus on tightly balanced rule sets and extensive replayability.

“Our game teams aren’t very big,” Forbes explained. “So those extra eyeballs really help us to evaluate what’s working with a design as we’re building it. The other thing that early access makes you focus on is making sure your game is both stable and fun the whole time you are working on it. It makes for fewer nasty surprises at the end of the project.”

He broke the process down further, clarifying how the alpha stage works as a major part of the project. “We actually have two versions of the game that players can play,” he said. “The ‘Stable’ version gets updates every three to four weeks. These tend to be pretty big feature pushes, like new card sets, quests, cards, etc. The other build is our ‘Experimental’ build. It updates several times a week—sometimes even multiple times per day, depending upon what we are working on. This build is decidedly less stable, and it is where we work out the details of the system with the players. We are constantly adjusting cards based on really specific feedback from our forums and in-game reporting system there.”

It’s not only the minor details of difficulty balancing that get worked out here either, as whole features can develop from their original intended role. For example, Forbes said, “You could always get pets in-game, but at release there wasn’t much to them. The first couple of big updates to Griftlands were all about getting, upgrading, and otherwise interacting with pets, because the players kept asking for it. People sure like their virtual pets!”

One challenge for Griftlands was balancing its narrative and character led RPG traits with the repetition of a roguelike. “We have players who love the story elements, but kind of muddle through the card play, and we have players who live for the cards but probably couldn’t tell you the protagonists’ names,” Forbes said. “Most players fall somewhere in the middle, and the exact degree of attachment they have to the two parts of the game will vary over time.”

Dealing with these different expectations from early on required some innovative solutions. “We tend to side-load a lot of the narrative,” Forbes said “So that it’s kept off of the critical play path. We try to meet players where they’re at when it comes to story content, so if you want to ask lore questions during a quest, they are there for you. If you want to learn more about the creatures and characters running around Havaria, it’s all discoverable within the game. But we try to make it as unobtrusive as possible, so that you don’t mind seeing it again on replay.”

If all this sounds like a long and costly method of development, it seems Klei has found a way to make it work. It’s especially noteworthy given the company’s stated commitments to avoid excessive working hours and create games without “losing their minds”. Forbes suggested that work-life balance is still a priority. “We’re pretty flexible with our deadlines and deliverables,” he said “If we’re approaching a release and it’s looking like we were a bit too ambitious, I’d much rather re-prioritize the features and push some stuff out than try to cram it all in and burn the team out. People produce their best work when they have time to pursue their life outside of work.”

An important factor here is that Klei’s games these days are self-published, which helps them control their development and release schedules. “I think that independence means we can take the time to make the best decisions for the game as we see it,” said Forbes. Indeed, perhaps Griftlands could not have become the game it is without the environment afforded by the company and its ability nowadays to fund its own projects. “Changing the design to incorporate the card combat would have been a pretty tough sell under a traditional publishing model, but we only had to convince ourselves (and then make it fun),” he said.

Griftlands thus appears to have evolved in a development model that fosters sustainable work practices, original ideas and community involvement. The identity in Klei’s games comes not only from the interesting choices they offer within carefully balanced rules and systems, but from focused teams given enough time and plentiful feedback to work out the wrinkles in their inspiration. Griftlands is still to be completed of course, but so far seems to exemplify what Klei as a whole has learned—playing your cards right can help you negotiate a better deal.

great read, thanks