Gone Fishing: Why the Fishing Mini Game Will Never Die Out

The afternoon is warm and slightly humid. Insects buzz around to say hello now and then. Dusk reflects off the water, and this wooden boat is surprisingly comfy. I cast my rod out a while ago—a Hylian Loach will bite soon, and everything is supremely chill.

I’ve never held a rod or touched a fish in my life, but this Wii remote and Twilight Princess makes me feel like a seasoned angler. I sit and think, “I can’t believe Breath of the Wild doesn’t have a fishing minigame.”

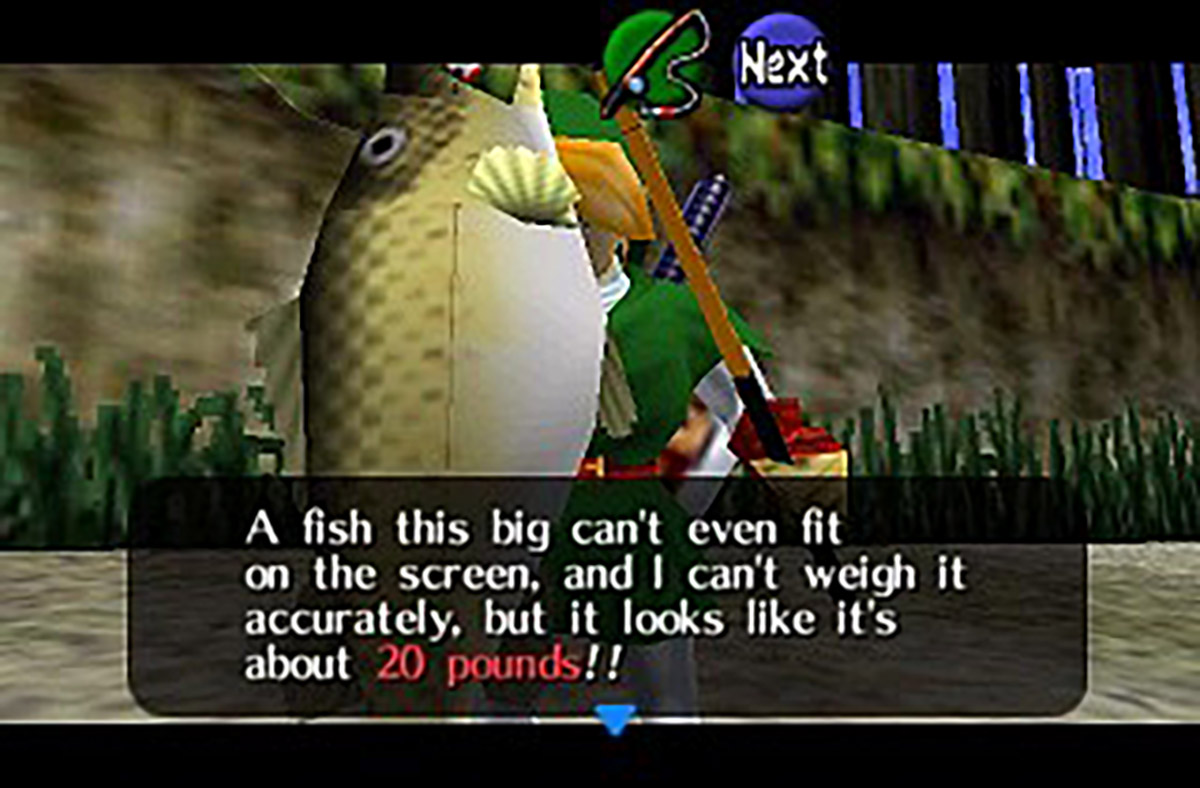

If you’ve played games, you’ve been a fisherman. Fishing is one of the few features which are ubiquitous in gaming: red health bars, blue mana pools, moving from left to right, etc. These aspects are the baseline to the experience and history of gaming, so it feels strange that fishing slots so well alongside them as one of the medium’s most recognizable aspects.

Whether you’re running through Hyrule Field, speedrunning Shovel Knight or simply hanging out with some pals in World of Warcraft, the humble fishing rod and bait is within arm’s reach; where there are games, there’s fishing. What is so calming and magnetic about fishing, and how has it interweaved itself into a variety of games?

In most cases, fishing is safe. Much like real life, it’s an opportunity to unwind and reflect. In some games, it’s a much-needed reprieve, whereas in others it can serve as a continuation of theme. Speaking broadly, virtual fishing isn’t as complicated or as taxing as real angling. It’s simpler, usually composed of three parts: luring, timing and catching. Typically, valuable fish are gated by more difficult or time-consuming processes. Overall, the entire structure of fishing in games, from reward to mechanics to its place in a game’s internal economy, feels satisfyingly simple, seemingly free from the frustrations of its real-life counterpart.

Where did fishing in games begin, anyway? 1984’s Sea Route to India is perhaps the earliest portrayal of a dedicated fishing minigame in the medium. To call Sea Route to India antiquated would be an understatement; as a curious text-based adventure in the mould of Oregon Trail, it’s interesting to see how similar its fishing blueprint is to modern efforts. Despite its age, it shares one significant overlap with today’s maritime adventures: timing. Players are tasked with dropping a fishing spear from their boat onto a whale as it moves across the screen, and success depends upon waiting for the perfect moment to hit them – it’s simple, but effective.

The fishing minigame in Sea Route To India feels unperturbed by age, a kind of noble longevity in a time of rapidly modernizing games. Despite there being 36 years of gaming history from then until now, the core foundation of the fishing minigame has largely stayed the same. The fishing minigame developed slowly after Sea Route to India’s release, but it only really became a fully-fleshed-out concept in 1993’s Breath of Fire.

In Breath of Fire, fishing spots could be selected on the world map. The minigame itself takes place via a side view – starter rods increase the difficulty, but end-game options decrease it and offer better rewards. Players are tasked with selecting the correct bait, casting out and reeling in at the right time. The “fight” then begins with two life bars representing the rod and the fish. Players must bring the fish to shore before either of the bars reach zero. It’s dead simple, but that’s all a fishing minigame really needs to be.

Breath of Fire III and IV are remembered fondly for refining the minigame’s design, but they are also remembered for having built upon the foundation of their predecessors by increasing the sense of reward fishing offers. The minigames offer useful items for combat, but the fish players catch can be traded for more coveted items and equipment. The minigames are as much celebrated for their significant rewards and economisation as they are for their design. The steady pace and flow of fishing means they are useful tools for developers to bundle extra content and rewards in.

This series is an example of where the fishing minigame became inextricably linked to RPGs. Even in modern variants, the structure and purpose of fishing remains intact.

Modern attempts at RPGs—whether it’s Nier Automata or World of Warcraft—can be guilty of being overburdened with systems; in times where system-driven lethargy occurs, the barebones nature of a fishing minigame can be an espresso-like experience of rejuvenation. As much as dense RPGs contrast with the simplicity of fishing, they can feel reliant on the minigame, too. For such a succinct periphery, fishing can not only offer a change of pace but also an additional avenue for players to spend time grinding out collectables or usable items. It hasn’t changed much since the halcyon days of Breath of Fire, but is that necessarily bad?

Almost everybody who has played a Pokémon game, too, can recall not only the calmness of fishing in the series but also the sense of surprise when catching a Magikarp, Feebas or another water type. Typically, these rod-caught Pokémon start off lackluster but soon evolve into memorable, powerful variants. This collective memory sticks out not just due to the rate of improvement these Pokémon have, but because of the combination of novelty, meaning and reward.

It’s surprising that it took the Final Fantasy series until VI to adopt some kind of fishing given its multi-layered benefits. The most modern Final Fantasy game, oddly enough, went all in on fishing and other antiquated side activities.

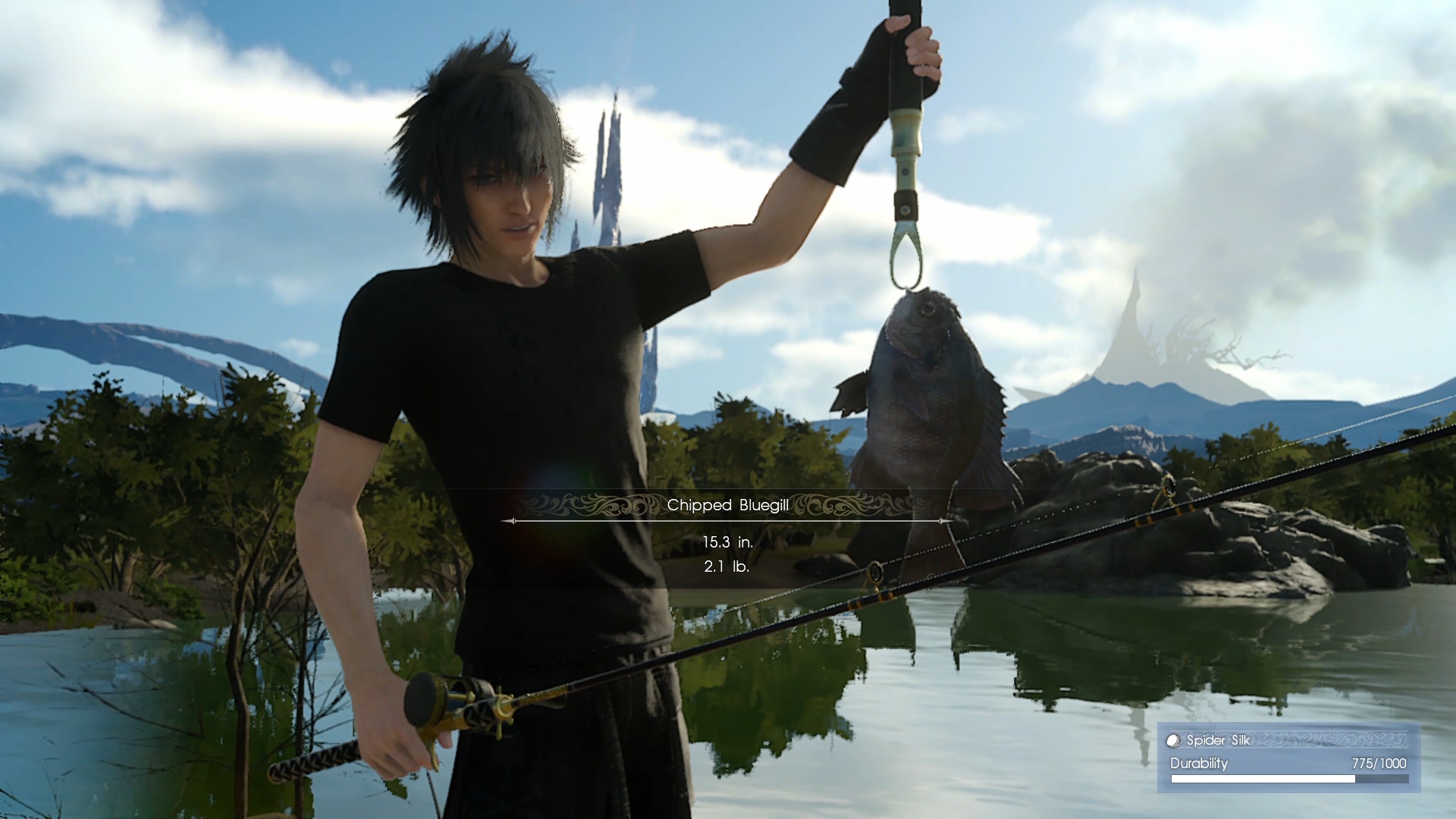

Final Fantasy XV is the most recent example of a game absolutely nailing its fishing minigame. While the title is a flawed gem, the one aspect that none of its fans or detractors argue about is its side activities. Not only is the fishing minigame one of the most enjoyable aspects of the game, but the rewards for the activity diversifies the game’s requirements for full completion, as well as providing ability points and some satisfying rewards.

Each party member in the game has a secondary purpose – Ignis cooks, Gladiolus manages the camp, Prompto snaps pictures and Noctis fishes. By being the only one in the party to fish, the rest of the group rely on Noctis. While fishing is optional, its implied importance to the group connects it to the game’s overarching themes of friendship, brotherhood and selflessness.

Thanks to this blend of fun design, thematic relevance and reward, Final Fantasy XV, while it divided opinion, found positive consensus through its inclusion of cohesive side-missions and minigames like fishing. Even though a significant amount of resources was plugged into its overarching systems, visuals and side content, the fishing minigame was its least-divisive aspect; in fact, it was one of the few parts of the game that was excellent.

Even in a game with confused delivery, a fishing minigame could still be lauded thanks to its design and sense of purpose. What Final Fantasy XV shows is that fishing minigames are at their best when they feel meaningful.

Fire Emblem: Three Houses managed to bundle in a sense of meaning into its side activities, too. Not only were side activities important for players who wished to expand their roster of students, but they also provided the raw materials for useful items during combat. Unsurprisingly, the game featured fishing that was direct and simple.

Even if fishing offered no reward in Three Houses, it would still be played and enjoyed. It’s a welcome break, a moment to reflect, a breath of fresh air from story stakes that quickly become claustrophobic. Fishing isn’t there to simply diversify gameplay or function as a time-dump for ardent completionists; sometimes, it just provides space where players can reflect.

At other times, fishing can act as a simple extension of a game’s theme or aesthetic. Animal Crossing is probably the closest a non-fishing game comes to having mandatory fishing, but the activity’s relaxed, calm vibe (for some) and straightforward design acts as a reiteration of the game’s ability to calm down its players.

In terms of gameplay, all players must do in Animal Crossing is cast out, wait for the fish to nibble, then press and hold a button when they bite. The mechanics are simple, but purposefully so; a complex fishing minigame would be out of tune with Animal Crossing’s meditative flow. By sticking to simplicity, fishing acts as an essential part of the game’s structure and aesthetic.

The same can be said of games in the same relaxed, pastoral vein such as Stardew Valley. For players who are optimising every part of their game, Stardew Valley is far from mellow, but for everyone else, everything about the game has a steady, calm pace. Even so, fishing still stands out as the go-to activity for blowing off some agricultural steam. Something about being close to water while quietly stockpiling fish ensures that fishing will always be the most calming aspect of a game.

In truth, there are poor examples of fishing in games. Fishing minigames tend to fall apart for two reasons: poorly paced difficulty or being mandatory.

Even the aforementioned Stardew Valley catches some flak for its interpretation of fishing, mostly because the difficulty isn’t paced as well as it could be. The learning curve starts off incredibly difficult before becoming very easy later.

Personally, I still have nightmares over fishing in Jak and Daxter, which required a herculean effort in both patience and dexterity. It was the antithesis of the good qualities of fishing, leaving its players in a frustrated mess that they probably still haven’t forgotten about. The issue with this minigame, too, was that it was a mandatory part of the story; when minigames are placed in a player’s path as a mandatory step, it robs them of their appeal. Fishing should be optional, a choice, not a challenge a player is forced to overcome. Whenever they need to be done, their negative aspects are compounded.

NieR was especially guilty of this, combining a mandatory fishing minigame with a paper-thin explanation. The mechanics were more complicated and obtuse than necessary – players had to pull back on the left stick when the rod bends, hold it, then when the fish pulls in the opposite direction, they then had to pull the stick to that direction while still holding it. It sounds easy, but in-game is a different story, plus it makes no attempt of explaining any of this to the player.

So, it’s not as easy as just placing fishing into a game and hoping for the best – it still needs to be clearly explained and be a part of a game’s peripheral elements, not in the main story. As a design tool, however, fishing is always an option for developers who want to populate open worlds or side activities. Their implementation is not a necessity, but they are still a system a designer can rely on.

Looking back at Sea Route To India, it’s a little unbelievable to think that a small part of a game from 1984 would be seeing similar interpretations of its mechanics today. While some may see that as a need for fishing to change, what it really shows is its unwavering ubiquity. It’s the “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” of game design.

Lots of players have never picked up a rod or fishing pole in their lives, yet can relate to the joy of a patient hobbyist’s big catch, the disappointment of a quiet day on the lake or the nail-biting anxiety of a trawlerman. We can understand why so many dedicate their free time or professional lives to the pursuit: Fishing in games reiterates the sanctity between us and water that we may otherwise be ignorant of.

In games, there is a guarantee that a fish will eventually come. In real life, there isn’t. Does this mean fishing in games is shallow in comparison? I’m not sure, but this Hylian Loach I’m reeling in sure feels like it’s worth the fight.

1 thought on “Gone Fishing: Why the Fishing Mini Game Will Never Die Out”