How Do You Make an Autistic Video Game?

It’s a strange time to be autistic. After years of existing at the periphery of public consciousness, we find ourselves enjoying an unprecedented level of exposure as a new and vibrant generation of autistic adults has come of age and entered the public sphere. And yet, for all this heightened visibility, the discourse surrounding autism remains frustratingly outmoded, often deferring to the same infantilising stereotypes and misconceptions that have permeated discussions of the condition for years now. Nowhere is this more glaringly obvious than representations of autism within popular culture, and video games are no exception.

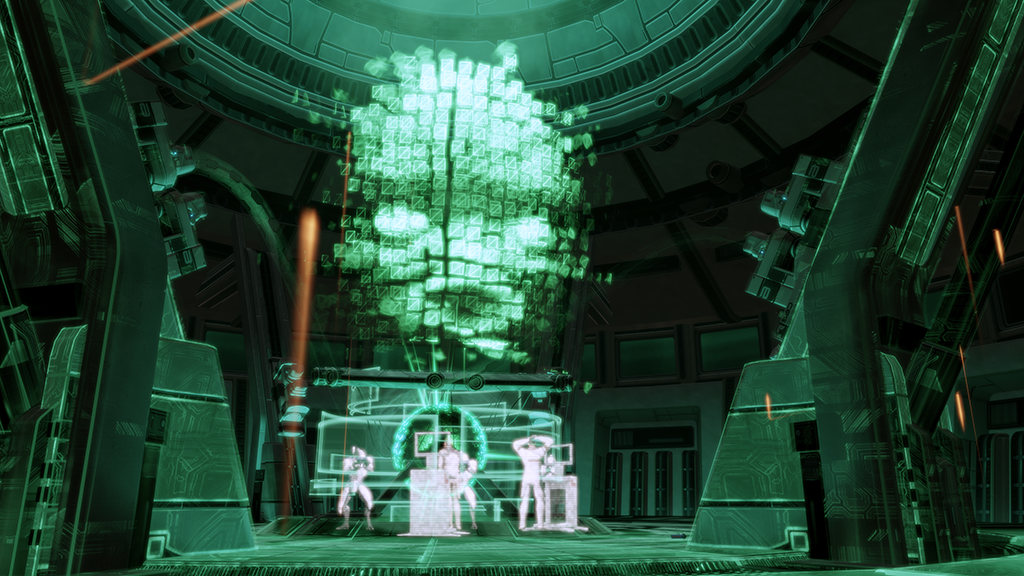

Perhaps one of the most notable examples of an autistic character within a video game is David Archer from Mass Effect 2’s Overlord expansion. At the start of the mission, we are told by scientist Gavin Archer, David’s brother, that as part of the titular Project Overlord David had volunteered to interface with a dangerous artificial intelligence for an experiment that subsequently went awry and that you must stop this AI (and by extension David) no matter the cost. As the player progresses through the facility however, they discover that David’s involvement was far from voluntary. Rather than choosing to partake in the experiment, Gavin forced his brother to interface with the AI, believing his autistic mind would prove invaluable to the project’s success (indeed in one particularly revolting scene, David is described as “literally a human computer”), and that his lashing out was in fact a desperate cry for help. Academically speaking, this is what we’d call a “yikes” situation.

It would be unfair to argue that David’s story is entirely devoid of value. Recently, Errol from the YouTube channel Game Assist (disclaimer: we know each other irl) produced an excellent video on this exact subject, noting how the relationship between David and his brother accurately reflects the abusive behaviours many caregivers exhibit towards autistic people. This is a dynamic seldom present in popular portrayals of autism where carers, even abusive ones, are often treated with an almost hagiographic reverence at the expense of their charges.

This is, however, as charitable an interpretation as one can lend to Overlord. In order to truly understand what David represents, we need to ask what his purpose is within Overlord’s story. In this regard, David functions as more of a narrative device than a person. At the start, he is presented as a violent, irrational force for ill, destroying everything in his path for seemingly no reason whatsoever. Yet by the story’s conclusion, he has transformed into an object of pity whose fate now rests in the hands of the player via one of Mass Effect’s famous moral choices. If the player is behaving virtuously, David will be removed from his brother’s “care” and taken to a specialised facility. Alternatively, the player can choose to leave him with Gavin, abandoning him to his abuser just so you can play the villain. At no point is David afforded any agency over his own fate. David is not a character, indeed as far as the story’s concerned, he is barely human. He is an object upon which the player enacts their will.

In the years following Overlord’s release, a number of more positive portrayals of autistic people have emerged, with one of the more interesting being Watch Dogs 2’s Josh Sauchak. Unlike David, the game affords Josh some influence over the game’s narrative trajectory. In one particularly delightful scene, Josh plays up his autistic mannerisms in order to dupe one of the game’s antagonists, demonstrating a degree of emotional intelligence that is very rarely granted us within popular culture. Nor is his autism shown to be an inherent tragedy. In one audiolog, it is revealed he has been profiled by CtOS, the game’s omnipresent surveillance network, which has marked him as childlike and mentally unstable based on his autism and his politics. In eschewing the orthodox framing of autism as tragedy, Josh’s problems are instead shown to stem from manmade structural injustices.

And yet, breath of fresh air as he is, there is room for improvement. Like David, Josh conforms to many of the stereotypes of the condition insofar as he is a white (presumably cis) male, a pervasive archetype that often overshadows autistic women and POC. I’m also not a fan of the Josh is described as operating on a “higher level” when it comes to computers, subtly ascribing superhuman attributes to the autistic mind most of us don’t possess. But more fundamentally, Josh for me represents a missed opportunity. Watch Dogs 2 is a game about the intersection of technology and structural injustice, and Josh’s experience with a pervasive and punitive system that deems him an invalid deserved a deeper analysis than a single audiolog. As such Josh’s autism, although astutely handled for the most part, is almost incidental. It’s an enormous improvement for certain, but there’s more that could be done.

Observing depictions of autism as an autistic person is a strange, almost uncanny experience not dissimilar to looking at oneself through one of those distorted fairground mirrors. You know it’s supposed to be you, indeed you might recognise aspects of yourself in the reflection. But the image you see is still warped, twisted in some capacity by its very design that renders your likeness imperfect. And the reason for this I believe is most renderings of autism within popular culture are not intended for autistic people. Rather, they are designed by and intended for a non-autistic audience. The most blatantly exploitative example of this is “inspiration porn”, a narrative style that sees disabled people reduced to passive and wretched recipients of generosity for the moral and emotional edification of the presumed non-disabled audience. It is this same infantilising logic that sees characters like David Archer being used as vectors for player agency. It is also what allows certain transphobic authors to use us as an argumentative device to be weaponized against trans people. In framing the autistic experience in relation to the neurotypical, autistic people are denied the capacity to be the agents of their own stories.

Conversations on representation are inexorably tied to notions of authenticity and in relation to autism, authenticity entails recreating the condition’s symptoms as accurately as possible. Accuracy is certainly important, don’t get me wrong, but there is a risk reducing autism to a series of affects whilst neglecting to explore it as an inseparable part of the human condition. So rather than simply presenting autism, how does one convey what our lived experience is like? This is largely conjecture on my part but rather than replicating the symptoms of autism in every minute detail, I believe it might be worthwhile for the medium to examine through less literal means. Video games have a unique capacity for metaphor in both their mechanics and spatial design which has been used to excellent effect in games like Silent Hill 2 to explore mental states such as guilt or grief through this ludic symbolism.

There are risks of course. Done poorly, I could see any attempt at representing autism through mechanics coming across as both pretentious and insensitive, and one should bear in mind there is no singular autistic experience (indeed autism invariably intersects with gender, race, class and sexuality). But a non-literal approach to autism, conveyed through mechanics is still worth a try, and could serve as a basis to explore the problems, positives and societal injustices that can typify with life on the spectrum. Video games are a wonderfully versatile medium with enormous potential to tell stories through active interaction. It’d be a shame if they were to waste that potential on creating yet another bloody Sheldon Cooper.

4 thoughts on “How Do You Make an Autistic Video Game?”