How the Polish Indie Scene Exploded in the Wake of the Witcher

At PAX West 2019, I went to breakfast with around a dozen Polish indie developers, the majority of whom were equipped with high-spec laptops housing early builds for upcoming games. As I nursed a lukewarm coffee, I made my way from table to table, experimenting with games as vast and varied as Paradise Lost and Ghost Runner (I didn’t manage to go hands-on with the latter, but the similarities to Mirror’s Edge showcased in the trailer have remained drilled into my memory ever since).

The following evening I attended an open-invite party and bumped into some familiar faces. We started to chat, and before long it became crystal clear to me: the Polish indie circuit has come onto the global scene with explosive force in recent years. Inevitably, this has a lot to do with the success of CD PROJEKT RED’s behemoth RPG The Witcher 3 — according to the 2019 Warsaw Video Games Industry Report, Warsaw-based studio CDPR became the first Polish company in history to be included in Bloomberg’s prestigious “50 Companies to Watch in 2020” list, comfortably nestled among the likes of corporate giants such as Netflix, Facebook, and Toyota. The same report concludes that according to statements from American multinational bank Morgan Stanley, CDPR’s value exceeded PLN 25 million in mid-November 2019.

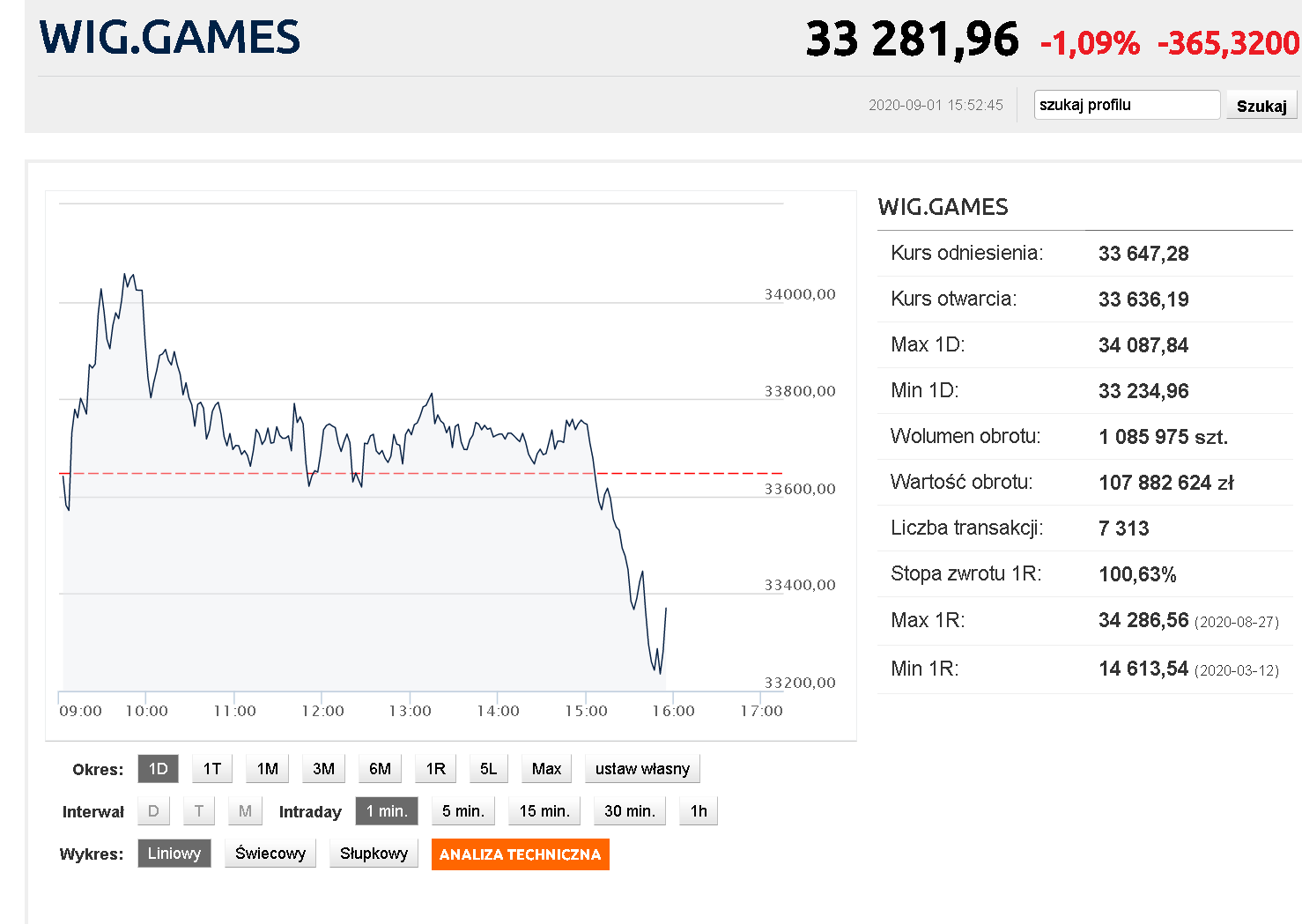

In order to trace the trajectory of the explosion in Poland’s game dev scene, I spoke with a range of indie developers and Piotr Gnyp, ex-EIC of Polish games magazine Polygamia.pl. Gnyp explains that there are over 400 studios in Poland right now, before noting that CDPR in particular is worth more than the second-largest bank in Poland. In recent years, the Warsaw stock market has actually carved out a special index — WIG.Games — reserved exclusively for the national games industry. “The role of [studios like] CDPR and Techland is enormous,” Gnyp tells me. “They were the first big game dev companies: people knew about them, worked for them, and learned how to make games — then they could quit and join other companies.”

Naturally, that’s largely where a substantial amount of critically-acclaimed Polish indie studios originated from. Although companies existed before CDPR — Gnyp signposts Metropolis Software, developers of Archangel and Gorky Zero — he maintains that “we can safely assume growth and prosperity started with the Witcher series.”

However, the industry goes back much further. “I am sort of the founding father of the Polish game dev industry,” Electro Body creator Maciek Miasik tells me. “In order to get into the industry, I had to build it — at least where PC game dev is concerned.”

Electro Body, which Miasik co-developed, serves a milestone in the Polish games industry in that it was one of the first PC games to hit the market. After Electro Body, Miasik created several of his own companies, among them Detalion and Pixel Crow, before eventually working on the original Witcher game as Head of Production. “For the last 30 years, I’ve been working in various roles as a producer, designer, programmer, and sound designer,” he explains. “I’m currently doing all those roles at once.”

Miasik tells me that Polish games have been available worldwide ever since the games industry initially came into being, which means Poland has been on the scene since the late ‘80s. Over the course of the last 40 years, Poland’s then dozen companies have evolved into hundreds of studios, both major and minor in scale. For every The Witcher 3, Frostpunk, and Dying Light, there is a Darkwood, The Vanishing of Ethan Carter, and 60 Seconds.

In Miasik’s eyes, his primary contribution is rooted in helping to kickstart the industry back in the ‘90s. After Electro Body, he went on to develop the first Polish game for EA: 1996’s FireFight. “When we were developing FireFight, we were regularly uploading builds via modem to California, usually at night,” Miasik says. “To our surprise, every day around midnight, the FTP transfers started to disconnect as if the whole internet halted to a crawl. We blamed the ISP, but realized that [although] local internet worked okay, the rest of the world was unreachable.”

“This was annoying as we were in the final stages of production and those uploads took hours,” Miasik continues. “Nobody wanted to sit through a night to oversee this boring process.” As it turns out, something was amiss — something… cosmic.

After deeming this as suspicious, Miasik investigated further and discovered an official note from the Polish backbone authority on a random Usenet group. Apparently, the satellite handling the majority of international internet traffic in Poland passed through the Earth’s shadow at midnight during the spring, which caused international relations to temporarily shut down every night. During this period, traffic had to be rerouted through easily-overloaded, bandwidth-limited ground connections.

“This is how the movement of astronomical bodies affected the Polish gamedev industry at some point,” Miasik says. It’s no wonder the scene has persisted since — if you can overcome the undying will of communication-impeding astronomical bodies, you’re in an industry destined to thrive.

As the industry continued to grow, it gradually began to earn legitimacy in the eyes of the Polish public. Artur Ganszyniec tells me he was hired by CDPR back in 2006 — a full 14 years after Miasik launched Electro Body. “Until then I worked as a data analyst in a big telecom company, and as a hobbyist tabletop RPG designer,” Ganszyniec explains. “A friend convinced me to join CDPR — at the time I wasn’t sure if making games was a good career move, but I was slowly dying in a corporate environment.”

Ganszyniec went on to become the lead story designer for the original Witcher game, but left CDPR after the preproduction phase of The Witcher 2. After spending six-years making F2P mobile games, as well as a stint building an 11 bit studios prototype, he started indie studio Different Tales with Jacek Brzeziński in 2018. They released their first game in late 2019: Wanderlust Travel Stories, or “an anthology of interactive travel literature,” according to Ganszyniec.

Ganszyniec explains that there were almost no professional developers around when he joined the industry back in ‘06. “We were learning as we went, without access to education, YouTube tutorials, or professional publications,” he tells me. Nowadays, designers, programmers, and artists are better educated and better prepared by the time they join the industry. Thanks to this running start, the average quality of Polish games has naturally improved. As a result, designing games is no longer perceived as merely a hobby, and the games industry has earned both recognition and respect on both the local and international stages.

Ganszyniec attributes this to the phenomenon in which developers like CDPR, 11 bit studios, and Techland managed to become household names. This movement succeeded in establishing games as not just toys, but as active voices in public debate. “If you look at this year’s nominations for Paszporty Polityki — a cultural award by one of the leading Polish magazines — for Digital Culture, you can notice that games were selected not for their gameplay or fun-factor, but based on what they say about the current political or cultural landscape,” Ganszyniec explains. “So I would say the main change in the industry was that it moved from a niche to [the] cultural mainstream.”

Although this process — this shift — has been drawn out over quite a long time, it continues to build momentum even now. “The Polish game dev scene is growing insanely fast, while also keeping close-knit ties to the people who helped build it from the ground up,” Greg Ciach tells me. The fact developers like Miasik and Ganszyniec are still around and actively participating in contemporary development testifies to this.

Ciach started his career at Firekom in 2012 and is currently hard at work on Paradise Lost, the debut game from his own studio, PolyAmorous. He explains that back in the ‘90s, the industry was “chaotic and messy,” but had a few shining stars in its oeuvre — among them Metropolis, Techland, and CDPR.

“But precious few games were created here,” Ciach continues. “Right now it’s the definition of AAA quality, with the names leading the industry’s evolution largely the same: CDPR, 11bit studios and The Astronauts — both companies built by the people from Metropolis — and Techland.”

Ciach explains that although the team at PolyAmorous are mostly quite young and are still relatively fresh to the scene, they have a couple of old-timers in their midst and actively try to help others wherever possible. As well as offering general advice, they consult with young companies by sometimes taking on the judge’s mantle and by helping with indie pitches.

This phenomenon extends throughout the Polish games industry as a whole, with a variety of other developers also seeking to play their part in encouraging fresh blood. “Sharing knowledge is deep-rooted in Polish game dev’s DNA” Ganszyniec explains. “I learned a lot by talking and sharing experiences with my fellow designers and I try to repay that debt the best I can.” Ganszyniec himself contributes to the ever-changing climate of game dev by teaching game and story design at the Lodz University of Technology, whereas Miasik teaches development-related subjects at Warsaw Film School, the Polish-Japanese Academy of Information Technology, and Game Dev School, while also volunteering at the Indie Games Poland Foundation. And it’s not just universities benefitting from this surge in education initiatives: Mielcarek tells me that on top of the lectures his team already provide at the Digital Dragons Academy, they recently started working with a high school in Kraków — something he is particularly excited about.

Bartek Nowakowski, who is responsible for sales and marketing at The Knights of Unity, began his games career after eschewing a cushy job at Google for a position at (then) a small Polish startup called Ten Square Games. “They were [made up of] 10 people with one Flash title, Let’s Fish,” Nowakowski explains. He notes that eight years on — as well as several since he left the company — TSG has exploded in size and become one of the major players in the local industry, currently employing about 150 people and being valued at roughly $400M.

According to Nowakowski, his current team at The Knights of Unity develop their own titles on work-for-hire bases while also occasionally indulging in outsourcing. “Our code can be found in Gwent Mobile, Disco Elysium, and PC Building Simulator,” he says.

Nowakowski draws similar conclusions to his fellow industry chums, noting that giants such as CDPR and Techland are largely leading the charge towards change in the Polish games sphere. “At Knights, we are contributing by sharing knowledge and organizing game jams,” he tells me. “Our blog is the second biggest Unity development blog worldwide — just after the official one — and this year we will be launching our own Unity academy: a course for C# developers who would like to switch profiles and get into gaming.”

However, although it is indisputable that the Polish industry has exploded over the last decade in particular, Mielcarek maintains that it’s still in the early stages of development. He notes that there still aren’t a whole lot of PR and marketing agencies available for consulting on a local level, and that the majority of Polish game trailers are created by the same company. He also doesn’t believe an agency specifically geared towards educating young studios on biz dev exists — not yet anyway. “You could say we have game-making studios in Poland,” he explains, “but there is no proper games industry yet.”

Despite this, Mielcarek still firmly believes the story so far is worthy of its own book. In fact, he singles out one that already exists: Nie tylko Wiedźmin by Marcin Kosman, which translates to Not Only The Witcher and was published in 2015. “It’s ridiculous to see how fast everything’s changing here,” he adds. “In 2014 I published an article saying that 129 studios had been working on 272 games. I believe there are more than three hundred game dev studios in Poland now, maybe more — it’s so difficult to keep track.” As Gnyp noted earlier in this report, that number has now shot past 400.

The industry’s growth reflects this. Draw Distance CEO Michal Mielcarek, who started his games career as a journalist back in 2003, explains that the games industry now receives government grants for R&D. On top of this, there are multiple Polish B2B events regularly scheduled throughout the year, such as Kraków’s Digital Dragons and Poznan’s Game Industry Conference. “We sponsor events like KRAKJAM, part of Global Game Jam, and attend monthly meetings with gamers and developers where we talk about games and development,” Mielcarek tells me. “And [we] drink beer.”

Despite these massive leaps in uniting the industry, the Witcher in the room still looms large. “A lot of Polish developers worked at CDPR, gained a lot of experience, and then left to join other companies or set up their own studios,” Mielcarek explains. The aforementioned Artur Ganszyniec and Maciek Miasik are just two examples of this. “[But] obviously there were [other] successful studios before The Witcher 3 launched. Techland created the Call of Juarez and Dead Island series. 11 bit studios released their awesome Anomaly series and This War of Mine. People Can Fly are responsible for Painkiller, Bulletstorm, and Gears of War: Judgment.” The list goes on.

But Mielcarek maintains that the success of The Witcher 3 was a different drowner. It radically changed the perception of game dev in Poland, both at home and on the global stage. “The government became very interested in helping the gaming sector,” Mielcarek explains. “There are over 20, maybe even 30 game dev studios listed on GPW (main stock) and NewConnect (alternative market). It’s easy to find investors willing to spend money on yet-another-gaming-company in Poland nowadays. And it might get even crazier if Cyberpunk 2077 is successful.”

“At the same time, it might be a very different story for all of us if it fails,” he adds. “Let’s hope it won’t.”

Meanwhile, Nowakowski points out that despite their size and reputation for blockbuster games, CDPR are still essentially an indie developer. “They’ve found a place where they can make great games and not force players to pay [for] crappy DLCs and microtransactions,” he explains. But he too is sceptical: “The problem is that even if they launch a great game, there is a chance it won’t stand against the hype they created. They have a great standing so far — we will see what the future brings.”

A range of other devs chime in on these sentiments too. Miasik — who, to reiterate, served as Head of Production on the first Witcher game — tells me that it was the enormousness of CDPR’s influence on the Polish industry that finally convinced the masses of how serious a business Polish game dev was. “Also, CDPR are masters of PR,” he continues. “Some of their stunts — like offering a copy of the game to the US President — showed the mainstream that games can be for everyone.

“The success of The Witcher and its perception — especially in the mainstream — helped the whole industry a lot,” he adds. “Investors started to pour in. Government officials started to talk to the industry and learn about its needs. The industry professionals earned their due respect.”

But despite the fact this was ostensibly a blessing, Miasik also points out the flipside: that now, in the wake of The Witcher 3, investors expect developers to replicate the successes of CDPR, except faster and with no risks. “When video games are mentioned during casual conversation, it’s always The Witcher,” he explains. “[They forget] that there were plenty of other well-known productions that were successful and very profitable.”

The difference is that “CDPR is a stock exchange powerhouse,” Ganszyniec says. “It made a Polish IP a major player on the international scene. On the other hand, I see the company as a reference point for negative management practices. I have a complicated relationship with CDPR — I love the games, I have the deepest respect for the team, and I admire how the company navigates tumultuous business waters. At the same time, when you look at the Polish game dev scene, you’ll find many small studios and many talented devs who at some time in the past were fired by CDPR or left because of burnout. But their creativity is not gone, it contributes to the industry as a whole. So, in my perspective, CDPR inadvertently created the Polish game dev industry we know.”