Identifying as a Marginalized Gender in Cosplay in 2020

Editor’s note: the original EGM piece this came from was started by Aimee Hart. Stephen Wilds took it over after the fact and is the one who brought it to Uppercut. Everyone is aware of the situation and has consented to this publication.

Many people enjoy dressing up to some degree. Whether it is for a formal dinner, Halloween, Renaissance fairs, or conventions, we find joy in wearing something nice, different, in tribute to an iconic figure. People wear costumes to imitate their favorite video game, comic book, or television character, some even going so far as to embrace the role itself—becoming them. Nobuyuki Takahashi created a word for this back in 1983, coining the term “cosplay,” and few foresaw the practice growing into the booming hobby it is today.

The word “cosplay” is a portmanteau that combines ‘costume’ and ‘play.’ It means: to show the love of someone’s favorite character, and allows someone to look scary or pretty while wearing fabulous things, experimenting with make-up, and momentarily living in another skin. The number of people who dress up to participate in the hobby for conventions like EGX, Dragon Con, Fanaime, and especially Comic-Con is enormous. Cosplay pictures from these events or of fans performing the art in their home is widely available and easy to find online. A growing number of people have even made cosplaying into a profession. Unlike the Maid Cafes in Japan or Medieval Times restaurants across North America—businesses with a model that incorporates cosplay for their workers to fit into a dining theme—many young costume-loving entrepreneurs have turned a hobby into an income-generating job as independent freelancers. Names like Meg Turney, Jessica Nigri, and Yaya Han are drawing a lot of attention and money—becoming household names in the cosplay arena.

Cosplay sounds like a fun idea: a world of glitz, glamour, and being cute, but having it as a job isn’t easy and the hobby itself can present problems for those wanting to explore it, especially those perceived as feminine. A majority of cosplayers are women—and though a growing number of cis-gender men are joining in, many of them lean toward male to female crossplay. For the most part, cosplay stems from the worlds of comic books and video games, industries that are traditionally run by men and have a history of exclusion. “You’ve now got a previously female-dominated hobby of sewing mixed into a male-dominated comic convention arena,” Carlye Starr, a clothing designer, seamstress, and lover of comic books said. “It was our way in and our way to shine.”

“Several aspects of cosplay are traditionally things that are more popular with women already: makeup, hair-styling, sewing, etc.,” according to a cosplayer named Luxlo. It’s easier for anyone to get into activities that are “more likely to include some things they already enjoy.” Many of them like to use their skills and creativity. Adaina Velez, a model and cosplayer, is a proponent of making costumes and props for the thrill of an impressive project. But to her, there is a different reason for them to do it, “it is a way for women to feel empowered.”

However, it is easy to feel small or cut down by others in the world of cosplay. It can be an open-minded and progressive community, but it’s not free of sexism and misogyny. “I’m not breaking any news cycles by mentioning Incels here,” Carlye said. “Many of these people cross over into fandoms,” and according to her, see the flesh-and-blood person doing the cosplay as a two-dimensional character for their enjoyment. Sexism and harassment in the cosplay community disproportionately affect marginalized people, and the cosplay community finds itself made up of many more women of color, trans, and non-binary individuals. These cosplayers can have a complicated experience while navigating the landscape.

Anette, aka Mighty Odango, identifies as gender-neutral and has been involved with cosplay for over 20 years. For them, the first step was getting into theatre, particularly The Rocky Horror Picture Show at the age of 16. “I’d always enjoyed dressing up for school, fancy dress days, and parties, and I did a lot of theatre and performance at school, so the characterization aspect appealed to me,” they said. Their statement rings true for many other cosplayers as well; getting into the role of a character wasn’t just appealing from a visual aspect, but an emotional one, too.

Over the years, Anette, their mother, and their friends banded together in order to help sew, craft and build cosplay costumes. Costume-crafting can be a daunting process, but the parts of cosplay assembly that Anette wasn’t good at, they quickly learned through experience. These skills helped them construct costumes of video game characters they wanted to become. “I’m especially proud of two from the Metal Gear Solid series. The first is Laughing Octopus, because it was completely unlike anything I’d ever made before, with a lot of prop work, electronics and problem-solving. It’s hellish to wear, but it has a lot of impact.”

That impact is what makes the discomfort worth it for many. Adaina said pointedly, “All cosplayers, regardless of sexual orientation (including myself), are attention-getters. At the end of the day, it all comes down to wanting to showcase our work because we are very proud of it.” Anette understands that and feels a connection. ”The second is The Boss, a character I’d been associated with by friends long before I even played the game myself, and one I feel very attached to since I have,” and it is easy to become devoted to a character, to feel connected, “people even use Boss as my nickname now!”

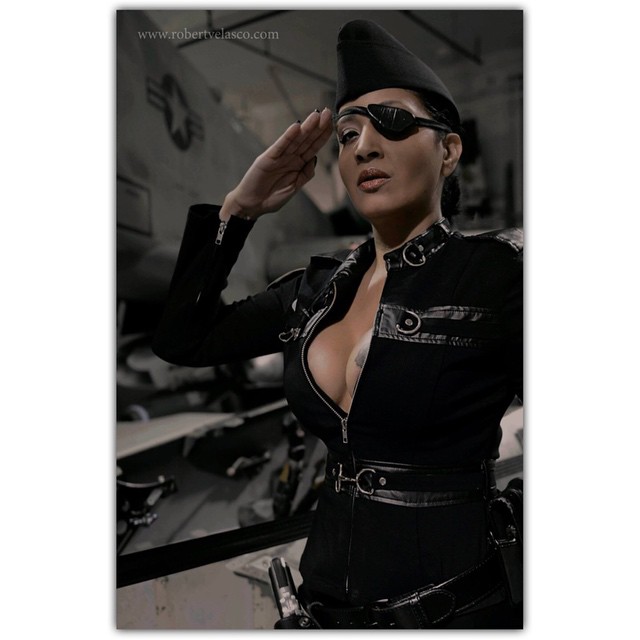

Some cosplayers try to stand out by remixing a costume, altering it into a sexier, more revealing version of the original character. Both the Boss and Laughing Octopus have outfits that allow more skin exposure, if the cosplayer wanted to do so. Cosplay can take many forms, and some prefer to express more seductive or lewd versions of characters. Boudoir photography—when a model poses as a character in lingerie, less about explicit nudity, but rather teasing it—has been steadily increasing in popularity over the years, giving a new avenue to those who want to overlay more sexuality with the character.

“Sexual cosplay is more suited to making money,” according to Carlye, but that doesn’t mean that everyone bows down to a crowd or the dollar. “I personally don’t feel “the need” to show more skin,” said Luxlo, “it’s just a style I began experimenting with more over the years naturally because I discovered that for me it’s fun, encourages me to love and work on my own body, and boosts my self-confidence. Seeing other women online posting boudoir modelling or confident sexy cosplay photos can be inspiring.”Adaina is also inspired by others, but sees showing more skin as a personal choice. “My followers appreciate the dedication and hard work that goes into said cosplays.” Whether she’s dressed as the leggy Elektra in all white or a version of Cassandra Cain that is covered from head to toe, she knows people will notice.

“Women who choose to cosplay sexy characters often receive a lot of unwarranted hate and harassment,” Luxlo said, “such as being called a long list of derogatory names, accused by fandom gatekeepers as not being “real fans”, hate targeted by Incels, and sexual harassment.” Many online insist that boudoir is not true cosplay, but that hasn’t stopped it from being part of the industry.

Remember Sexy Pikachu by Jessica Nigri back in 2009? While not lewd, it oozed sex appeal and since then, has influenced—intentionally or not—not only how we view cosplayers, but how some cosplayers may view themselves. “Nigri taught us women that it is okay to not be screen accurate,” Adaina said excitedly, “that it’s okay to tastefully make any character sexy.” While many fans do point to this moment as a turning point, Carlye filled us in a bit on the long road to it. “Yaya Han blazed that trail long before. Jessica [Nigri] has the trifecta of Western beauty ideals, but we have had so many other sexy cosplayers before her. We have to acknowledge Ruby Rocket, Belle Chere and Riddle. “

Some, like Anette, don’t feel the pressure to show more skin, but when they do wear less, it is due to how they view themselves while cosplaying in the first place. “For me, there’s a degree of separation from it. It’s not me wearing that outfit, it’s the character,” Anette explained, also noting that they are usually surrounded by friends when cosplaying, so they feel safer to participate. “Though, if I were 18 and starting cosplay today, I imagine I’d feel much more pressure in that regard,” they said. “As cosplay moves more towards being on online media rather than in person, it becomes harder to stand out and feel validated, and being sexually appealing is an obvious and relatively simple way to do so.

It’s hard to argue that, “social media consumption in general, such as browsing Instagram, has pressured women to look a certain way,” Luxlo said. “It is similar in or outside of cosplay. We can scroll through countless pictures a day of what we perceive to be beautiful and see the “likes” and comments they receive and wish to achieve a similar look.” That can cause a negative effect. “It distorts their own perception of beauty, how they look, or how others look,” Luxlo said. This doesn’t mean that everyone conforms to the ideal. “I’m really proud of the women out there showing body-positive photos and being real with the younger generation of cosplayers,” Carlye said. She wants to set an example for others, “if you are ever going to have body augmentation, do it for you and your happiness, not for others.”

Of course, there are cosplayers who don’t necessarily feel the pressure, but are very much aware that sex appeal can help in building both a career and influence in cosplay. A cosplayer who goes by the name of Tansura T (girldissolving), Tansuru, or Tans to their friends, started cosplay back in 2001 during middle school and went to Otakon, an annual convention in Baltimore that anime fans are fond of. After seeing everyone in costume and falling in love with the environment and people there, Tansura returned the following year as Sailor Saturn from the Sailor Moon anime. Although they had been immediately drawn into the world of cosplay, it was obvious that things weren’t quite so clean-cut.

“I don’t feel pressured to [flaunt sex appeal]. I do feel like I get passed over more often for not conforming to the standard of attraction, and maybe if I conformed, I would get more attention.” Tansura later clarified that they did respect the hustle. “If you want to do sexy cosplay and even better, if people are going to pay you for those sorts of photos, you know, get your money. It takes a lot of work.” But sex appeal isn’t the hardest obstacle for Tansura. A particular oppression follows people of color in the cosplay world, particularly those who are Black. It is a constant reminder of how much the white cosplay community, from its cosplayers to its photographers, still has to understand and learn.

“Cosplay is a cis-gender and white-dominated hobby,” Carlye said. “I’ve known some trail-blazing POC cosplayers and it’s been so hard for them. They are passed up and looked over. Photographers won’t book them and contests won’t acknowledge them.” Adaina, on the other hand, hasn’t experienced such issues and feels, “blessed to have been kissed by the sun at birth.” Luxlo said she believes that race definitely impacts a cosplayer’s reach, but more importantly that it, “doesn’t take long to be in the cosplay community and see the abundant amount of racism and hate,” and furthermore, “it’s sad how obsessed many cosplayers and non-cosplayers alike are with the idea of cosplay “accuracy” and tying that to the color of one’s skin. Some people absurdly expect real people cosplaying characters to have the exact same skin colour, facial features, and body proportions as them.”

“I think more people are aware now of some issues such as how race-facing (altering your skin colour just for cosplay to resemble a POC) is wrong and harmful, but there are still many people who do it and defend it,” Luxlo said, a claim that Carlye backed up. “We are still seeing white cosplayers do blackface,” yet she went on to say how non-white cosplayers are ridiculed for being Sailor Moon. “It has to stop.”

“The hardest thing for me is being a black and dark-skinned cosplayer,” Tansura said, recalling the times they were shunned by a number of photographers due to not fitting the “standard” of what cosplayers were expected to look like. It got so bad that Tansura wanted to start doing photography themselves. “I was sick of it” they said. “If it’s happening to me, I’m sure it’s happening to other people. And I don’t want people to feel like this.” Being passed over for not representing white beauty has affected a number of POC cosplayers, and when examining the social media currency of likes and retweets, the disparity is more obvious. As Tansura puts it, “darker-skinned cosplayers get overlooked all the time, and we’re doing amazing work.”

Beyond racism, the cosplay community also suffers from rampant sexism, harassment and sexual misconduct. This behavior, which doesn’t reflect the cosplay community as a whole, led to a movement that first appeared during New York Comic Con in 2014: Cosplay is Not Consent.

“The “Cosplay is not Consent” movement has helped with the way women have been treated at cons,” said Adaina, and its purpose is simple: regardless of what the cosplayer is wearing, it does not give anyone permission to touch them in any way that they deem inappropriate. It also targets against stalking and harassment of all kinds. For Luxlo, there is more the convention coordinators could do by, “supporting women and cosplayers,” but more importantly, “not continue inviting guests that have had multiple accusations of sexual harassment or otherwise that makes many attendees feel uncomfortable.”

Tansura spoke about their time cosplaying, when predatory behavior wasn’t just coming from other peers, but photographers too. “I’m very rarely a target for that kind of thing. Again, I think that being non-binary and black plays a part of that. But I’ve worked with photographers who haven’t acted predatory around me and then found out later that ‘oh, they’re a huge creeper and they’ve hurt others in the community’ and I’m taking photos with them? It makes me feel sick.”

Luxlo believes that as much as things are slowly improving, there are numerous challenges left to face. “Many men still trying to gatekeep their fandom or communities,” and that isn’t just at the conventions, but every day online as well. “It’s not uncommon to see transphobic slurs in the comments on cosplayers’ photos, such as the term “trap”, which seems to have become very popular in the anime and “nerd” communities.” Carlye sees it too in how fans react to women. “Unfortunately a confident woman is still a threat and we have to actively start changing that. You’ve got women who are being praised for their form and skill, but have to maintain a humble social media or face the wrath of all.”

She noted a few bad apples in the community that cause friction, “Alisa Kiss was always a problematic figure. She was cold and unsupportive of other cosplayers. She got away with this by being white, blonde and classically sexy.” Carlye explained further, “When she came out as a white supremacist you had a huge fraction of humans unsurprised.” She was still supported by admirers after this, another bad actor allowed to stay in. “We need accountability, not only with the artist, but the fans,” Carlye said. “Sexy humans are in abundance so you can be discerning on who you support.” Most importantly, both Carlye and Adaina believe the biggest challenge is still demanding overall respect.

With the bad, of course, there is good. Cosplay expression can provide healing, for example. Tansura realized they were non-binary during a convention, while talking about dressing as Finn who first appeared in Star Wars: The Force Awakens. Finn ended up being integral to Tansura’s realization. “Actually it was funny. I realized I was non-binary while I was in the middle of a panel talking about cosplay. It was weird. I stopped and was like ‘oh shit!’” Cosplay helped Anette express their love for characters and hang out with friends in an activity that was not quite like sharing a pint, but made them laugh and feel loved all the same.

From self-discovery to finding friendship and community, cosplay is an admirable and enviable hobby. Yet, there is more still to be done before identifying/presenting as a woman in cosplay can be considered a wholly safe practice—a shame for what is otherwise a glamorous and fun expressive outlet.

2 thoughts on “Identifying as a Marginalized Gender in Cosplay in 2020”