Mandinga: A Tale of Banzo & Faith As Power

The first time I encountered capoeira, the Brazilian martial art practiced by enslaved Africans under Portuguese rule, I was 8 years old controlling Eddy Gordo in Tekken 3.

The summer after fourth or fifth grade my uncle died and he is buried according to his Muslim faith: wrapped in white linens and laid directly into an embrace of earth. I think, “I would like to be buried like this, too.” I miss him.

Suddenly it is 2010 and the largest Brazilian man I have ever met, Jeromin, is laughing softly through as much English as he can muster. I do not understand Portuguese, but when he speaks his native tongue we are both more relaxed. Carolina Saores is singing “A Hora É Essa” through Phone speakers and I am beginning to cry. During my second year of university I discover that the orixa Obatala is neither masculine nor feminine and I begin to understand something about myself.

I love video games. You do too, I presume. A personal gripe I have with the industry is a lack of martial arts diversity. China, Korea and Japan reign supreme in martial arts representation with Muay Thai and English boxing following closely, but India and the entirety of Africa are bizarrely absent; again, a personal gripe. I also find it rare that games actually affect me on a spiritual level. It’s not often at all that a video game main character is given a recognizable, real world faith with a large population of living adherents.

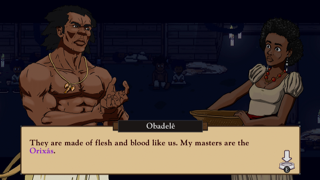

Register my shock as I came across a little indie game from a small Brazilian studio that features capoeira as a primary combat mechanic. Mandinga: A Tale of Banzo is a story that conjectures how two men of faith might object to white supremacy and their enslavement in Portuguese colonized Brazil. The story isn’t biographical, but it draws on real historical elements and themes. It follows Akil, a Muslim ‘earner slave’, and Obadelê, a Yoruba field slave.

Akil’s faith gives him community in a world where he is profoundly isolated. His position as an earner slave separates him from the other field slaves in what seems like a dual operation of a personal sense of superiority and chattel slavery’s attempt to prevent rebellious solidarity. Even in this isolation, self and otherwise-imposed, Akil has community in his faith.

I am not a Muslim and having grown up in the Black Baptist Church tradition, I was surrounded by a pervasive, weird Islamophobia. My last pastor once explicitly stated in a sort of jealous aside that the congregation’s missionary work had to improve because Islam was the faster growing faith community in the city; Islamophobia is weird.

After leaving the church, Islam was one of the faith avenues I considered– having been close to one of my Muslim uncles and finding the religious structure of the community more codified. There is a time to pray particular words in a particular direction in a particular manner. Even alone, there are others who are with you in ways that my Christian prayer community lacked. Akil has this. He is an enslaved man. It appears that his best friend is a donkey. But when it is time to pray in the evening, he is not alone because the Muslim community prays at that time. He is with even as he is alone.

Seeing a Muslim man be Muslim without reservation, without fear—insofar as an enslaved man lacks fear—without the weird Islamophobia I grew up with is deeply satisfying. Again, I’m not Muslim, but much of Islam brings me peace. I feel safe when I pass a masjid or a mosque, especially at night. Seeing his character simply be Muslim in colonized Brazil, which was and still is deeply Catholic, affects me.

Obadelê’s character is Yoruba and keeps faith in the orixa, spiritual beings who function like deities but who are not deities in the normative Western sense. Orixa are more accurately the culmination of power between the universe, humans and nature. Some of them are responsible for the creation of the Universe, of humans, of the natural world and some preside over war, agriculture, and the oceans. For the sake of respecting Yoruba and the Afro-spiritual diaspora where orixa are acknowledged, I’ve operated within the definitions of the cosmology properly. Obadelê’s faith is earnest and firm in a really refreshing way. His cousin is shocked when he reminds her that he still believes, and believes defiantly. She fears for him but his faith keeps him unshaken.

It is not a simple “belief” either. Largely, African spirituality is more socially integrated than Western Christianity. Obadelê doesn’t just believe in the orixa, he has an active faith that they will literally be intimately involved in whatever needs to happen so that his freedom and security is guaranteed. There is a tendency in the West to portray African spirituality as inherently evil or “hopeless,” a constant threat to Christian or Islamic hegemony, identity and orthodoxy. They raise zombies and have scary chants; so spooky! Here, Obadelê’s faith is earnest and a bit innocent: it is unaffected by his circumstances, even reinforced by them. The orixa are given a sense of integrity through Obadelê’s faith. When he needs them they will be present. I know African spirituality is like this, but it’s few and far between that I see mainstream Western media also acknowledge this.

Games as a medium have a tendency, in my experience, to treat spirituality and religion either as problems to be solved or for the main character to experience by proxy. Faith is often a lore dump instead of an actual way of defining a character, your character, and how they interact with the world. God of War positions you as a demigod and then proceeds to have you murder most of a pantheon. The franchise’s 2018 continuation does a great job letting the character deal with these ramifications, but we still don’t see regular people engaging with their faith in these gods, many of whom are now dead. Raji: An Ancient Epic features the Hindu mythos as living, the protagonist is an active participant in an ongoing tale and her faith in its cosmic narrators is a primary reason why she persists. Dear industry: this is good, more of this. Other games might have you choose a god as a passive bonus mechanic, but not really do anything else with that relationship.

In Mandinga, faith is power. It is not some generalized conception of religion or deification. Akil is Muslim; he prays in the direction of Mecca to Allah. Two items that Akil can use are ‘Healing Words’ which the game describes as ‘the healing words of Allah,’ and ‘Words of Power’ which is described as ‘words of wise Allah to inspire your children.’ His unlockable abilities are explicitly Islamic when not simply related to the technical act of firing his gun. You literally invoke the names of Allah like Al-Mutakabbir (The Dominant One) and Al-Qawiyy (The Strong One) to defeat your enemies. Al-Qahhar means ‘The All-Prevailing One’, and as the penultimate ability in Akil’s skill tree it does damage to enemies and grants buffs to our player characters and allies.

Obadelê, on the other hand, draws strength from the orixa through jewelry, trinkets, and weapons attributed to them. Obadelê specifically has abilities invoking Ogun for strength, Omulu for health, and Xango in the penultimate position for a similar effect as Akil’s. There is a section of the game that allows Obadelê to find objects belonging to specific orixa and return them. This is how the story portrays Obadelê’s faith in the orixa and their involvement with the mundane. The Abrahamic religions do not often feature the intercession of G-d, God or Allah without some intermediary like a prophet or angelic herald. African spirituality mostly disregards intermediaries: the orixa are the power and will show up personally.

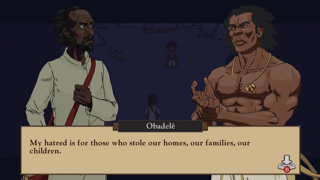

All of this power is not without a target, and honestly the most satisfying part of our heroes’ journeys: all this power is in service of opposing white supremacy. Akil’s relationship to his enslavement is complicated by his status as an ‘earner slave.’ He’s literate and is thus allowed to move freely between the plantation and a small marketplace to sell goods. This puts him at a sort of odds with field slaves, like Obadelê; it gives him a kind of superiority complex that he struggles against in the story, especially its early hours. Akil enjoys the mild, conditional freedom he has and doesn’t want to jeopardize it, which is understandable. Obadelê has no reservations or complicated notions of who is evil in his life: white people.

White people uphold the system of slavery that tras the both of them. Obadelê despises this system and whoever operates to uphold it. Our heroes use their faith to kill the white people who oppress them. (There is an achievement called ‘Oppressing the Oppressors’ and it is good.) Akil is hesitant at first as he both doesn’t want to jeopardize his conditionally good standing with the white society that enslaves him, and also finds murder objectionable within the purview of his faith. But white supremacy says he’s a slave, and in the story he’s on the run; slavers’ capture or kill policies don’t give Akil room to be a pacifist or apologetic. Obadelê, when given the chance to kill his oppressors to protect his path out of enslavement, takes it and regrets nothing about it. He protects his and Akil’s fragile freedom, in the words of a rather famous Muslim, “by any means necessary.” In the name of Allah and by the strength of Ogun, these white people have to die.

It is an historical fact that most media seems to struggle with for whitev–I mean whatever reason. For much of the histories of Black people across this planet spanning several continents, white people are the primary evil. I mean ‘evil,’ by the way. Chattel slavery in the Americas was a particularly grotesque iteration of humanity’s overall inclination towards forced labor. The game’s inciting incident is the (suggested) rape and murder of an enslaved woman—Obadelê’s cousin—which Akil witnesses. Mandinga doesn’t expound much about the atrocities of chattel slavery because it doesn’t have to. It simply lets you object to the whole of the system by killing its agents in the name of Allah and by the strength of Ogun. This is not something I get to do in most media, particularly not video games. Not only do these Black men have interiority as characters, but their interiority is defined primarily by faiths that are routinely disrespected by the white supremacy that existed then and that we live in today. For six hours I was able to invoke the name of Allah down the barrel of a gun aimed at white people who would rather deny a Black man his right to be free. For six hours I was able to use capoeira—a martial art I practice, that I’ve only seen in fighting games until now—in its original culture, context and purpose infused with a spirituality I operate within to declare that a man will not be chained. It is incredible.

It may be unnecessary to say this, but I really believe in the deepest parts of myself that representation matters. In Mandinga, Muslim people get to defend themselves against injustice without reservation. The 99 Names of Allah are not fodder in order to make a story exotic, they exist to give 2 billion alive-right-now Muslim people peace, hope, security. Practitioners of Voodoo, Candomble and Yoruba traditions are not an opportunity to design shadowy enemy factions. The orixa are not enigmatic boogeymen from the secret depths of forest tribes that exist to terrorise innocent white communities or corrupt other organized religions. Faith is a guide by which people deal with difficult situations.

But you mentioned the characters kill lots of white people; should white people play this game? White people should absolutely and immediately play Mandinga: A Tale of Banzo. As uncomfortable as it may make white people to experience Black characters enacting anti-colonialist revolutionary violence, I promise you it is more uncomfortable for Black people to reckon with the legacy of colonialism, imperialism, and slavery.

Truly, there is something beautiful about seeing faith so reverentially applied to a story about liberation. It is also a deep act of healing, as a Black person, to be able to reject grotesque institutional injustice by the aid of powers that cannot be touched by any institution of man. As hard as colonial Brazil, the Papacy, and white supremacy more broadly may have tried for centuries to erase the breadth and depth of what belief means for Africans and their descendants, they failed. Mandinga is the result of why that is important not just to Black people but important to the historical record of the planet itself.

Games can be empathy engines: they allow us to embody other people and, specifically, the interiority of other people. Real faiths exist and when we play games that respectfully represent those faiths we can deepen the empathic bonds that allow us to recognisze that we all are born human and free. Remembering that none of us is entitled to keep another enslaved matters. Mandinga portrays, without apology, that there are powers above and among the mundane that can be the shield and the spear that ensures our liberation.

What platforms and/or where can we access the game? Is the game dialogue available in multiple languages (arabic?).

It would be awesome to put together a series along the lines of “stop playing a stereotype: games for antiracists” or something more imaginative, in the same spirit.

As we grow we seem to stop recognizing how much we learn from every feedback providing medium we interact with – we learn subconsciously and at times, consciously, from video games. And yet, we are rarely critical of them, and the huge lack of diversity in the industry that creates them.

the game currently only available on Steam for PC. it supports Brasilian Portuguese (the native language of the devs as far as i know–the studio is Brasil based) and English.

a series like that sounds like a great idea actually…

uppercutcrit is definitely trying its best to inject this industry with as much deep feedback as it can!