Metro: Exodus-Home is Where Your Stuff Is

The most important mission I embarked on in a game this year was up a tower in Metro Exodus. It wasn’t a particularly impressive tower. As a matter of fact, it looked like it was barely being kept together. One good storm could roll in and topple it, forcing the bandits who called it home to find somewhere else to try and carve out a life. And make no mistake it was definitely a home, or as close to home as you could turn a radio tower in the apocalypse. Plates sat on surface next to a pot over a furnace; I’d interrupted dinner likely. Across from that stood a bunk bed and on the floor above there was another, beside it a lit candle and a small radio. Just outside on what you’d call their balcony sat a chess board and hugging the frigid railing was what I’d come for. I moved through the camp messily, arrived at the top of the tower, and claimed what I’d done all that hard work for: a worn down guitar. It’s the heart of this and every home of the apocalypse.

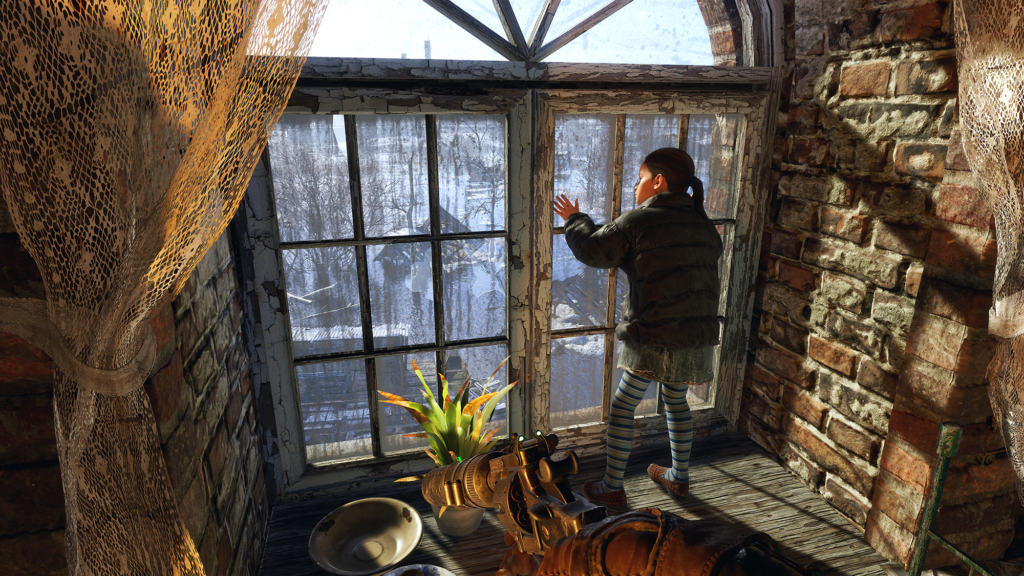

Guitars become a bit of a recurring motif in Metro Exodus. Playing one is how Stepan likes to spend his downtime, frequently performing for the woman we found on the Volga River and who he falls in love with. I caught these performances quite often when we were traveling between locales and had the time and space to breathe. I learned eventually that I grabbed the guitar from that tower so that there could be a second one on board the train I now called home. Before one performance, he prompted me to grab it and join him in a song. Now this simple little thing had brought not just the happy couple together, but had brought me closer to them. In the world of mutants, marauders, and the bitter cold of nuclear winters, we found warmth and normalcy in the simple things.

Down the line, I met an admiral who resided alone at a saw mill, but surrounded himself with the bodies of his men. They had a seat at his dinner table, one of them with a guitar propped in his hand. After divulging his personal history to me over tea, I was made to pick up the instrument and play, eventually lulling him to sleep. Despite the fact that I was a stranger in his home, hearing me play that melody he recalled, really hearing anyone but himself, made my presence one he wanted to keep around. He invited me to stay with him, saying that the next night he would set me up with a bunk and though I regrettably couldn’t stay, I played him out so that just this once he wasn’t alone.

The Metro series is one inexplicably drawn to the idea of things. When the end of the world happens, do things serve us similarly? Do they carry the same weight or are they changed? Do we have any more things or do we need to make new ones? The answers to these questions are difficult ones to come to but one thing’s for sure: everything is invariably changed. Things that were taken advantage of before find new, deeper meaning. The trains people traveled in and the tunnels they flew through became new homes. The bullets we used to wage war now act as both protection and currency. Guitars that were once just instruments bring communities together in song and dance, communities that had nothing before that.

It’s also a series about fitting humanity in where you can. When you’re busy fighting to survive, can you afford to just chill? Often you can’t, but Metro tries to find time for you to be able to. More often than not these instances of reprieve are carried by something. You’ll step out of a train car, hang over the railing and have a smoke. Sometimes you’ll sit down and get boozed up with friends. And yes, other times you’ll play the guitar. It’s about doing what you can with what you have to ensure you still feel and don’t grow hollow.

“At the end of everything, hold onto anything.” These words from one of my favorite games, Night in the Woods, probably best describe the attitudes of the people staring the down the actual end of everything in Metro Exodus. In the former, things don’t really stop and the end is metaphorical. In the game the line originates from, it’s a sentiment about the fleeting nature of things, especially as life marches on. “Across both games exists a longing for what came before and a despair that it can’t be the same anymore and yet the cast of both keep fighting for something, anything to get them by.” In Metro, there aren’t very many things to hold onto and most things aren’t fleeting, they’re outright gone. The end did happen and so they’ve got to try that much harder to cling to anything, to carve out a home, and to find a family. In Metro, things end and it’s on you to make them begin again. You’d think they couldn’t make it, but they do and it’s in large part to things like that guitar that they do.

I don’t have to worry about the end of the world, at least not immediately. My things won’t lose their meaning in the wake of the apocalypse but I also don’t have to wait till then for them to mean something to me. I’m free to live my life and see my friends and family and sit in my room, perfectly filled with things I’ve collected or that have been passed on to me. And maybe this is a weird takeaway but I love each and every single thing that much more since playing Metro Exodus. I look that much harder at them before I leave or enter. I sit in a room with an R2-D2 figure at the door. R2 has the most hats, including ones from a brewery in Boston, a college in Albany, and a Night in the Woods one that says “Crimes” under the visor. Above all that hangs a frame with art and accompanying quotes from NITW. My drawer is littered with figures of Red from Transistor, the gang from NITW, Lee from Telltale’s The Walking Dead and a Funko Pop of Rory Gilmore. A record player sits on one end and a Pip-Boy from Fallout occupies the other, and atop the Pip-Boy there are two plushes: one of Koro Sensei from Assassination Classroom and another of a black sheep. And there, in the corner of that room adorned with gifts from friends that mean the world to me, sits a guitar, and I know I’m home.

Excellent piece!