Nemesis is the terrifying bioweapon the evil Umbrella Corporation sends after Jill and her team.

Monster Therapy: How I’m Using Survival Horror Games to Deal With Coronavirus

In cheesy slasher movies, the climax of the story is almost always a chase scene. Our intrepid hero flees their masked assailant, scampering through undergrowth, slamming doors, knocking over bookcases, anything to slow the antagonist’s progress. But nothing seems to faze the killer. They punch through every wall, push aside every obstacle, and shrug off every blow, until the scrappy survivor figures out how to jury-rig the perfect way to slay the beast—at least until the inevitable sequel, of course. That’s the moment when the protagonist gains control of their situation for the first time – in video game terms, when they finally manage to deal damage to the boss. Roll credits.

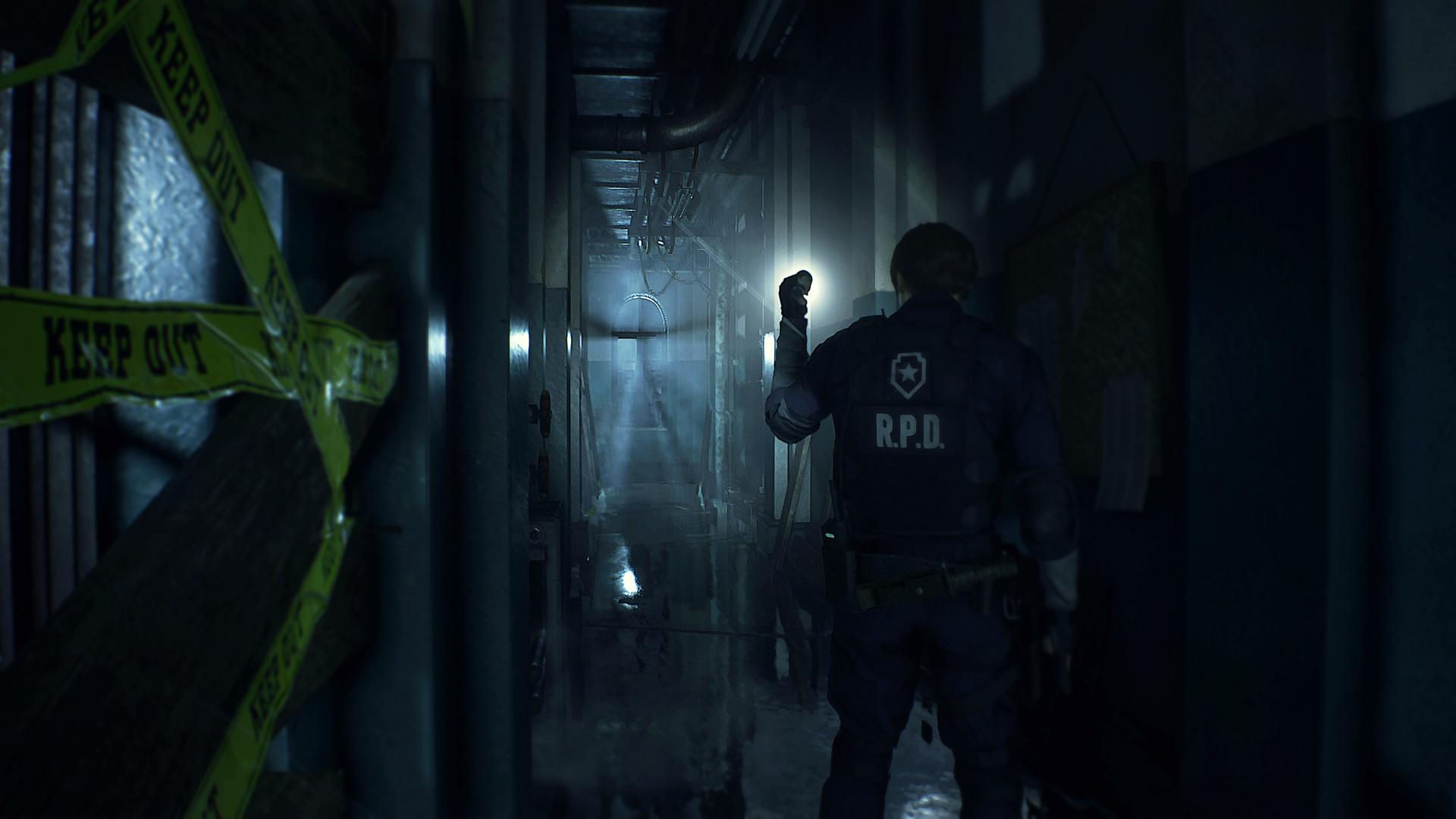

That climactic struggle between hunter and quarry forms the backbone of the recently released Resident Evil 3 remake. The original game carried the subtitle Nemesis on its release in 1999, for good reason—the team envisioned the entire game as an extended clash between heroine Jill Valentine and the eponymous Tyrant. True to that vision, you can’t go very far in the remake without running into Nemesis in one of his many forms, each more outlandish than the last. Following in the heels of Resident Evil 2’s revamped Mr. X, who hounds Leon and Claire as they explore that impossibly ornate police station for hours at a time, Nemesis is a souped-up superpredator with many more tricks up his sleeve than his trenchcoated predecessor. But while these clashes ultimately veer towards absurdity by the end of the game, I couldn’t help but appreciate how his brute simplicity overturned my well-laid plans at every turn.

When I was a teenager, I devoured horror-tinged shooters like Condemned: Criminal Origins and F.E.A.R., but it wasn’t until I encountered Frictional Games’ Penumbra series that I fully embraced horror as an artform unto itself. Ever since the Resident Evil 2 remake made me freshly recognize the appeal of survival horror, I told myself I would make time to check out older games in the genre. Like many similar pledges, that idea quickly got buried under a pile of timely articles, interview transcriptions, and shiny new games that I just had to check out. Over the past two weeks, stuck inside my 600-square foot apartment with my significant other and our very cute cat, I’ve found myself reaching for a specific type of experience to deal with the mounting stress. It’s not a cutesy fantasy of idyllic island living that I’ve craved; it’s digging through filing cabinets to try to find the right combination of herbs to survive the next bite from a diseased dog.

To be fair, I can absolutely understand why droves of people have retreated to the comforting bosom of games like Animal Crossing: New Horizons as the world has rapidly transformed to deal with an unprecedented crisis. But, personally, I’ve found that running away from shambling terrors and counting the bullets left in my gun a lot more effective at disarming my recurrent anxiety than hawking fish and bugs to pay my virtual mortgage. While it’s certainly not for everyone, I think there are a few good reasons why the blind terror of sprinting away from Nemesis and other survival horror baddies is helping me cope with the very real terrors outside of our doors right now—and it has to do with catharsis and the very appeal of the form itself.

Critics have long argued that horror is at its best when the faceless monster serves as a metaphor for our creeping anxieties. From racism (Get Out) to misogyny (The Witch) to consumerist culture (the criminally underrated Halloween III: Season of the Witch), the genre can literally embody our suppressed fears, casting them as skulking monstrosities that peer at us from behind closed blinds or ambush us from around a corner. As the saying goes, you can kill a man, but you can’t kill an idea; turned around, you can’t kill your fears, but if they’re made manifest in an eight-foot tall killing machine, you can at least try to blow them up.

In general, horror games have a tendency to lift their best ideas from other media in the genre, especially films. (There’s definitely an argument to be made that the very opposite happened with the original Resident Evil and the subsequent revival of the zombie film subgenre, but that’s a discussion for another day.) With his slow gait, intimidating stature, and commitment to ripping you apart at close range, Mr. X in particular owes an obvious debt of gratitude to classic slasher villains like Friday the 13th’s Jason Voorhees and Halloween’s Michael Myers.

When I play games, I tend to over-plan my every move, sometimes to the point of absurdity. Even when it comes to relaxing fare like Animal Crossing, I feel the need to optimize my island’s output, planting trees in carefully-considered areas, eking every single Bell I can get before the day’s close. In horror games like Resident Evil 3, however, I don’t get that option, because big baddies like Nemesis bust through the door and dash my plans. Since I spend my days compulsively reading about the Covid-19 era for my job, my brain appreciates the break. Just like Nemesis, there’s nothing I can do about it, and there’s something comforting about that.

In terms of fully embodying their concept of the invulnerable pursuer, I would actually argue that Mr. X fits the bill more than Nemesis. I spent hours ducking in safe rooms, listening for his heavy footfalls, trying to plan out the perfect route so I didn’t have to resort to kiting him around library tables and other open spaces. The rules of engagement surrounding him were very clear: Since you could sprint slightly faster than him, you could always get away from him if you took smart routes that were clear of foes. None of my deaths that were caused by Mr. X actually came at his hand; the constant pressure of his presence would cause me to make mistakes, to forget about the Licker lurking in the hallway, or to try to sidle past a gaggle of zombies that would bite off most of my health.

If Mr. X is a fully fledged game mechanic that can be circumvented and planned around, Nemesis feels more like a stage-specific hazard that keeps reinventing itself to test your mettle. For one thing, simply running away from him isn’t a valid strategy; in many cases, he’ll break into a sprint to close the distance between you quite quickly, or he’ll hook your leg with his arm-tentacles to pull you back towards him. In either case, you have to use the new RE3-specific dodge to avoid his punches and keep moving. At times, I felt that Nemesis had more in common with the boulders that you run away from in Crash Bandicoot than the monsters that inspired him. I found myself forced to keep the camera on him at all times to try to read his animations, Dark Souls–style, which caused me to run Jill headlong into walls or into the waiting arms of enemy zombies.

As you explore deeper into the maw of Raccoon City, Nemesis starts to pull out increasingly far-fetched weapons to try to stop you in your tracks, from flamethrowers to laser-guided rocket launchers. Resident Evil has always struggled to balance its action-movie impulses with the vulnerable humanity of its protagonists, and it’s fair to say that RE3 can sometimes veer a little too close to Paul W. S. Anderson’s frenetic film adaptations, especially near the end of the game. It’s laudable that it manages to build to an explosive finale—with boss fights that are, for my money, much more engaging than those in the RE2 remake—but, at times, I found myself yearning for the more muted horror of its predecessor.

For me, the appeal of the survival horror genre lies in its tense decision-making, and the resource management that comes along with that. Should you sacrifice your last grenade to clear this zombie-choked corridor, or should you try to kneecap those directly in your path and make a run for it? My playstyle tends towards the slow and conservative: I strive to control as many areas as possible while using the least amount of ammo possible, at least in my initial playthrough. The sudden shock of having to give up that control to an invulnerable foe like Nemesis—and the process of wrenching it back, either by escaping or defeating him temporarily in battle—is the kind of power fantasy that I need right now.

While it’s certainly true that the best horror monsters represent the everyday traumas that many of us have to deal with, I personally don’t want to be reminded of them right now. I’m a freelance writer, and I’ve already had several important pieces cancelled because of the COVID-19 crisis. Several of my friends are sick from the virus, and even more have been laid off or had their hours cut due to the economic ravagement that’s taking place around us right now. When I smash a tiny, knife-toting flesh-sack to death in the halls of an elementary school in Silent Hill, that tells me something about protagonist Harry Mason’s character. But it also reminds me of things I don’t want to think about right now, like how this crisis is going to affect the elementary school students that my mom teaches in rural South Carolina.

Nemesis might scare me when he busts through a wall, but there’s no poignant metaphor hiding behind his melted monster-face. He’s a big dumb monster that wants to kill me, and I have to run away from him. Right now, I need entertainment that tickles my lizard brain on that level, that calls all my nerves to attention—simple problems with simple solutions. Fight-or-flight. In the world of survival horror games, even the biggest, baddest bad guy goes down with enough bullets. Resident Evil delivers on that level, and I have plenty more of them to play. Now let’s see that Code Veronica remake, please.