Of Rats and Men: How a Lurid 1974 Best-Seller Revolutionized Strategy Games

There’s a good chance that if it weren’t for James Herbert I would never have written about games, at least not in English. Well, a “good” chance may be overselling it. Stephen King was, naturally, my first choice during those mid-’80s summer holidays when I started noting down every unfamiliar word encountered in my afternoon reading, while family and friends were splayed on beds and couches throughout the sun-drenched house, snoring happily, shaking off the blissful exhaustion of a full morning at Tolo beach followed by a hearty meal at the local tavern, the two so conveniently adjacent you didn’t even bother wearing your flip-flops for lunch.

But there are only so many paperbacks by the same author a small seaside kiosk can host, words already crowded by revolving racks of cheap sunglasses and a menagerie of inflatable waterfowl, not to mention the spots on the stand already claimed by the altogether different terrors of Jackie Collins and Robert Ludlum. So, at some point, because it was either this or Hollywood Wives, I “downgraded” to the world’s second-most famous horror writer at the time and ended up reading The Rats.

Herbert’s other major contribution to the medium—roughly at the same time I was reluctantly becoming acquainted with him while vacationing in Eastern Peloponnese—was inspiring a traditional publisher, one with more than a century’s history, to make its first foray into video games. Hodder & Stoughton was no stranger to innovating when it came to peddling its often sensationalist output. In the 1920s it anticipated Penguin’s paperback revolution with the mass-produced “yellow jackets,” a line so successful, it was lifted wholesale by Italian publishing giant Mondadori for its own libri gialli, in turn providing the collective term for the gaudy, operatic nightmares taking over European cinemas in the ’70s.

The Rats, Herbert’s debut novel, released in 1974 while Dario Argento and Lucio Fulci were near the peak of their creative powers, offered a grittier, though no less lurid, alternative. A gory work of unabashed classploitation, its hordes of murderous rodents spread through a decrepit East End still pockmarked by WWII bombsites in a near-dystopian world where humans and beasts alike are innervated by just two elemental predispositions—violence in pursuit of survival and sex in pursuit of gratification. (The promise of apocalypse would be properly explored in the third part of what was to develop into a series of books, Domain, where the swarm infests a post-nuclear London.) Naturally, The Rats was a massive, controversy-fueled success, its initial run of 100,000 copies exhausted within weeks.

Here’s where things get interesting for the aspiring video game publisher, though. By the time Hodder & Stoughton came up with the idea to adapt Herbert’s debut, a decade after its release, the medium’s high-culture aspirations were still tethered to literary ideals. The concept of the “interactive movie” had yet to catch hold, its inevitable emergence delayed by the restrictions of 8-bit technology and floppy-based storage. Instead, text adventures, rebranded under the more highbrow label of “interactive fiction,” were marketed by Infocom as the next step in the evolution of the literary arts. Telarium was collaborating with sci-fi gods Ray Bradbury and Arthur C. Clarke. Synapse enlisted an honest-to-god future Poet Laureate to create Mindwheel (in fact, Robert Pinsky was so enamoured of this new medium that, while he enthusiastically contributed to the game, he wasn’t at all keen to work on its accompanying book). Rather than visual spectacle, “serious” games in the mid-’80s delivered words. A text adventure seemed the safe, obvious choice for Hodder & Stoughton, especially as its first digital release was to be, you know, an adaptation of a novel. Still, whether due to a genuine desire for innovation, concerns that the schlocky material couldn’t compete with that of the publisher’s highly esteemed peers, or good old-fashioned cluelessness, H&S gave us a unique hybrid instead—arguably the world’s first narrative-driven real-time strategy game.

Not that the source material didn’t lend itself to the genre. Starting with isolated encounters between smaller but unusually aggressive packs of rats and a group of boozed up vagrants here or a pupil taking an ill-advised shortcut there, over the course of a few days the attacks in the book spread across East London, from Shadwell to Poplar, the swarm emboldened by the leadership of unusually large, unnaturally intelligent specimens. To Herbert’s credit, he never stoops to pretending the rat threat could ever be a match for the fully mobilized defence mechanisms of an advanced Western nation. But he’s happy to let the rodents wreak havoc in the city’s poorer districts for a while, thinning out the capital’s lowest social substrata as bureaucracy’s rusty cogs groan at the bothersome effort of protecting the riff-raff. Owing to numbers, cunning, and circumstance, the rats cause chaos at a screening, overrun a school, and even derail an underground train before some semblance of organized resistance is mounted, the delay enough for Herbert to deliver a blunt but effective message on where Westminster’s priorities lie.

Aiming to unsettle like its literary springboard, the video game adaptation of The Rats declares its intentions with a chilling introduction. A short paragraph recounts the discovery of the first devoured victims before concluding, matter-of-factly, that the balance of power between humans and rodents has shifted. But it’s the subsequent animated sequence that has remained etched on the memory of anyone who watched it at the time. The beam of a flashlight flutters across a dank cellar, trying to catch the shape scampering behind its crumbling walls. The world outside the edges of this anemic light is pure darkness. Then a pair of ferocious red eyes appear, momentarily followed by another, then another. The swarm rushes towards the screen as if threatening to crash through the panel, its leader jumping out of the shadows and straight for the player’s jugular. Blood spatters across the title.

You are now safe to start.

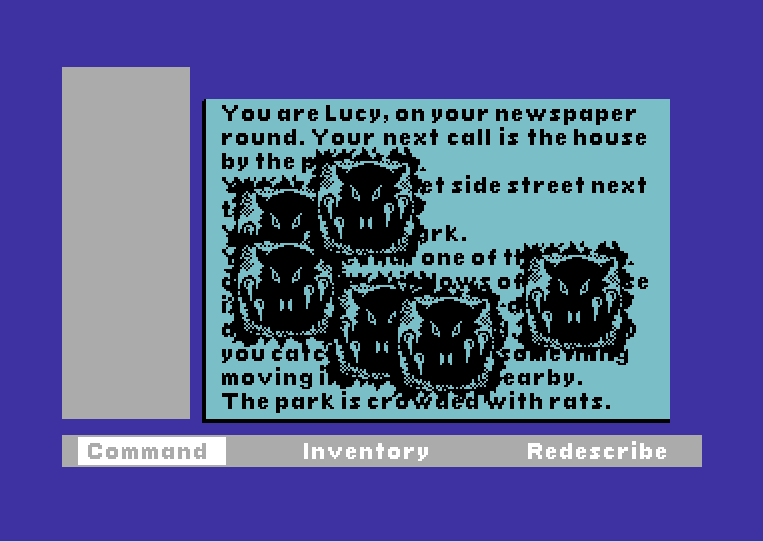

The respite is short-lived. Before allowing you to oversee London’s defense from the safety of a sealed operations room, The Rats wants to showcase its vicious adversaries up close and personal. Selecting randomly from a series of gory vignettes (some of which were borrowed from the novel, some written exclusively for the game), you’re cast as the protagonist in a tense text-adventure minigame, presenting you with a limited number of options and severe time constraints. Linger too long or take a wrong step and your charge will expire under a carpet of bristled black fur and gleaming incisors: Errol, the ticket inspector wondering what’s delaying the 8:15 line again; Henry, the besieged shopkeeper mounting a desperate last stand through creative application of household chemicals; and, most shockingly, Paula, having already lost her dog to the neighborhood’s new apex predators and now desperately trying to protect her helpless baby. In Danse Macabre, a book-length treatise on his favorite genre, Stephen King famously proclaimed, “If I find that I cannot terrify, I will try to horrify, and if I find that I cannot horrify, I’ll go for the gross-out.” At times it feels Herbert’s rodents, both in the game and the novel that inspired it, have little respect for this hierarchy of decent taste and jump directly onto the third option with savage glee.

The kind of decentralized, faceless, barely understood threat so effectively outlined in these interludes has become the quintessential adversary type in strategy nowadays, especially for titles revolving around longer, story-based campaigns, from the invading alien force of XCOM to the rogue spy network in Phantom Doctrine. There is a reason for that: Not only does the element of unfamiliarity tend to congeal into immediately arresting storylines (at least for mainstream audiences less interested in, say, the minutiae of terrain effects and musket reloading times); it also provides a convincing narrative justification for the mechanics of research-based progress that have emerged as a genre staple since the early 1990s and remained an essential component to its enduring popularity.

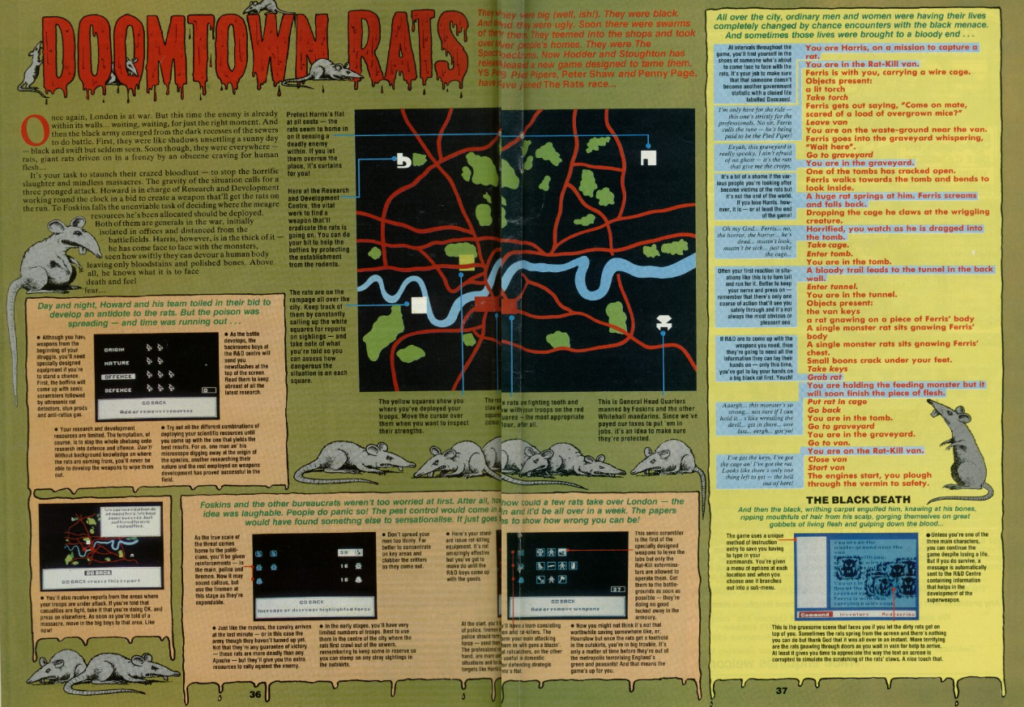

Not that we get anything comparable to Civilization’s tech trees in The Rats. Research is organized in the simplest of ways. Ten available scientists split however you see fit among four labs focus on different aspects of the threat: the rats’ physiology, the origins of their newfound belligerence, ways to defend against the fatal disease they carry, and technologies to assist in their extermination. The resulting knowledge and gadgets, things like ultrasonic scramblers and specially modified flamethrowers, are produced at regular intervals through largely invisible procedures. Still, developer Five Ways Software (who had previously adapted Lone Wolf playbooks for the ZX Spectrum, surely an influence on The Rats’ unique hybrid) showed an instinctive grasp of the potential synergy between narrative and resource management by shrewdly linking your performance during the vignettes to research progress. Assuming, for example, that Laura, the papergirl, manages to escape her ill-advised foray into the strangely deserted house she notices during her rounds, her experience may provide insight into how the swarm organizes itself and boost research in the respective field.

In a world where The Banner Saga exists, that may sound like a fairly basic structure, but in 1985 there was nothing quite like The Rats. The market was dominated, that being the era of yuppies and jingoism, by aggressively titled Wall Street simulators (Acquire, Asset Stripper) and wargaming-inspired historical reenactment scenarios (Gettysburg: The Turning Point, Battle for Normandy), the latter churned out on an almost monthly basis by genre stalwart Strategic Simulations, Inc. Yet here was Hoddard & Stoughton, a first-time game publisher, making its debut with an unprecedented blend of adventure and tactics, viewed from the perspective of multiple characters, and pitting the player against a horrifying, ever-evolving threat.

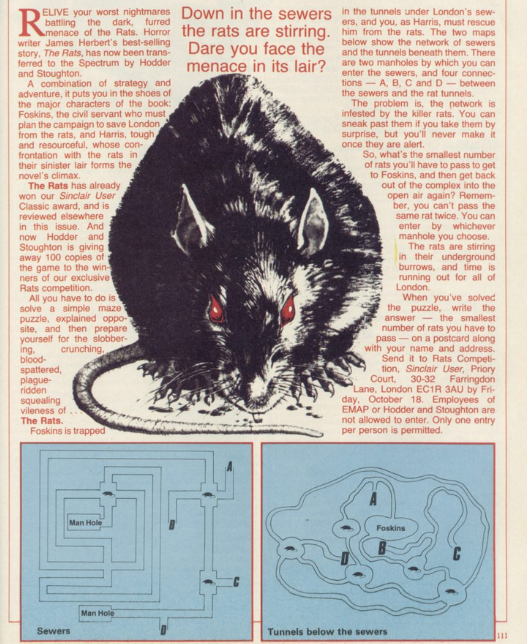

Impressively, Five Ways’ innovations do not stop at these unconventional features. Even the traditional strategy bits of The Rats are groundbreaking in their use of real-time mechanics. Once you’ve (hopefully) survived your opening encounter and assigned research, you’re given the role of Foskins, the book’s unlikable Under-Secretary of State and presented with a 20-by-15 grid of London where blinking lights indicate possible sightings of the swarm. Your main task is to examine reports, decide which are genuine and which are mere byproducts of the hysteria gripping the English capital, then equip and deploy your limited force of firefighters, police officers, and exterminators hoping your hunch was accurate and, if so, that your squad is sturdy enough not to get butchered while still conserving enough firepower to handle the next emergency.

Although real-time tactics were not unheard of in the medium (in his Ars Technica piece, Richard Moss traces their origins to the 1981 title Utopia for the Intellivision), they were still exceedingly rare and had hitherto been used exclusively to imbue the relatively inaccessible strategy genre with more broadly appealing action elements. Never before had a developer merged the two approaches in order to enhance its storytelling, to add an extra layer of tension on top of an already oppressive narrative of working-class suffering, monstrous invaders, and government incompetence. Just like there was no time to think in the interludes (which also operated under real-time rules), the flickering lights on your tactical map unbearably punctuated your mistakes, each decision charged with a sense of urgency that turn-based approaches simply could not generate—the ticking clock of a losing war.

If there is one issue with the mounting desperation creatively imposed by Five Ways’ decision to go real-time, it’s the way it tends to deflate Herbert’s anti-establishment anger. (In a delightful retrospective, horror author Grady Hendrix describes the novel as the literary version of “Anarchy in the U.K.”: “gripping you by the collar and screaming in your face.”) Sitting at the edge of your seat as Foskins, eyes glued to the screen for the next sighting, does not exactly convey government indifference. Perhaps, if a trace of the book’s political subtext remains in the game, it’s found in the way the latter splits responsibilities between the former’s two protagonists: the Under-Secretary safely controlling operations from the base while Harris, the schoolteacher, scours the field during the interludes, capturing live specimens, losing companions, and, ultimately, playing a pivotal role in the final showdown with the swarm.

An amalgam of seemingly disparate elements, a mutated freak in its own right, The Rats was met with a lukewarm reception when released in late 1985, with the novel optionally included for an extra couple of quid. Critics were torn between appreciation for its novelty and confusion, the stalemate decided on a rather unfortunate technicality. The excruciating loading system, implemented to randomize the interludes’ order, allowed no restarts, meaning that, in the event of losing, one had to rewind the tape and start the long process over. In one of the most favorable reviews, Zzap! 64’s Sean Masterson described it as “a mixture of innovative successes and miserable shortcomings… [that] don’t really exist in the game, but rather around it”—a sentiment shared by Crash’s Derek Brewster, who spent roughly half his allotted word count expounding on the game’s loading woes.

Not only did those issues put off contemporary audiences, derailing the enshrinement of a potential classic, they also became the reason the game’s Commodore 64 version remained unavailable in anything but the original cassette format for more than two decades, as even sophisticated emulators were unable to handle its idiosyncratic loader. A fortnight of hectic collaborative tinkering on the forums of Lemon 64 (one of the biggest online communities for the popular computer) during the summer of 2006 ended this period of imposed obscurity by splicing together a workable digital copy, leading to at least some possibility of a reappraisal.

Yet, despite a retrospective Eurogamer review the following year pronouncing it “one of the most unique 8-bit games ever made,” Hodder & Stoughton’s first and only foray into the medium still languishes in obscurity. Like Herbert who, despite having sold more than 50 million books in the prolific decade following his debut, is seldom cited as one of the greats, the sole videogame adaptation of his work lurks in the shadows of more polished if less adventurous titles. Even still, The Rats’ DNA is splattered, barely visible, across the hallowed halls of the strategy genre.