Image Source: UN

Planetary Play: Games and the Environment

The practice of temporarily habitating virtual worlds teeming with digital life may not seem like an obvious starting point for an article related to climate change. How does the pixelated idyllicism of Stardew Valley relate to the dense, dangerous jungles of Green Hell, or the ashen ruins of Dark Souls? And how can we mobilise our knowledge of these crafted digital worlds to aid our understanding of real-life climate change?

Investigation into ecologically-focused video games, or eco-games, is a relatively new field of academic research which began with Barton’s 2008 paper on the absence of player character reactions to weather in video games. However, there is currently no commonly accepted definition for an eco-game. For some, they are deliberately designed to engage players with environmental thinking for the purpose of generating positive environmental behaviours. For others, this is decarbonising and making environmentally friendly the production process.. Universally recognised, however, is the power of video games as a medium of communication. The sheer scale of the gaming community, currently sitting at over three billion players globally, has attracted international attention for environmental communication. They have even been recognised by the United Nations who have released multiple ‘Playing for the Planet’ reports, which describe and explain how the gaming industry has, and could, adopt environmental nudges to make players think about the effects of their effects on environments and ecologies. Given the identification of video games as a potentially potent media for climate change communication, how can positive environmental thinking be promoted within them?

Generally, when we play games, we internalise the logic of them in order to continue playing aiming for completion. The progression structure can be broadly described in a few small steps:

- To complete the game, I need to progress

- To progress, I need to complete this level

- To complete this level, I need to overcome this challenge

- To overcome this challenge, I need to utilise my skill

- The more skill I acquire, the more likely I am to complete the game

In-game environments provide the structure of interactive fantasy, the physical and narrative boundaries in which skills, challenges, and levels are tightly woven together. We explore these alternative realities – seeking out their mysteries, solving puzzles, and mastering mechanics. However, beyond the ludic qualities of games, they can act as a means of understanding the realities they are derived from. For example, in Red Dead Redemption 2 (RDR2), successfully hunting animals requires a keen understanding of the animal itself. While hunting a bear, the open arid plains aren’t the best place to look; instead forests at craggy foothills become your destination. Then begins the tracking process, which could involve careful movement and observation as you stalk your quarry but, typically for me, results in crashing through the undergrowth, swinging bait and brandishing a shotgun.

As an abstraction of a reality, RDR2 creates an immersive world through coherence, credibility, and consistency. Just as physical objects, e.g. bullets, act in accordance with physics, the simulated natural world does too. Players act, and the game responds. As computing power and design ambitions increase, so does simulation potential. Whilst environmental fidelity has risen – there remains an opportunity to capitalise upon the interactive nature of videogames to communicate processes of climate change in a more personal manner – away from the current dominance of statistical reporting and cataclysmic imagery in mainstream media.

There are games available with core environmental narratives, such as Alba: A Wildlife Story and Beyond Blue. These deal with specific issues – pollution and resource extraction respectively – but there is a gap in the current market for harnessing the computational power of gaming to reveal the causes and impacts of climate change which, at the time of writing, only one game has attempted to address.

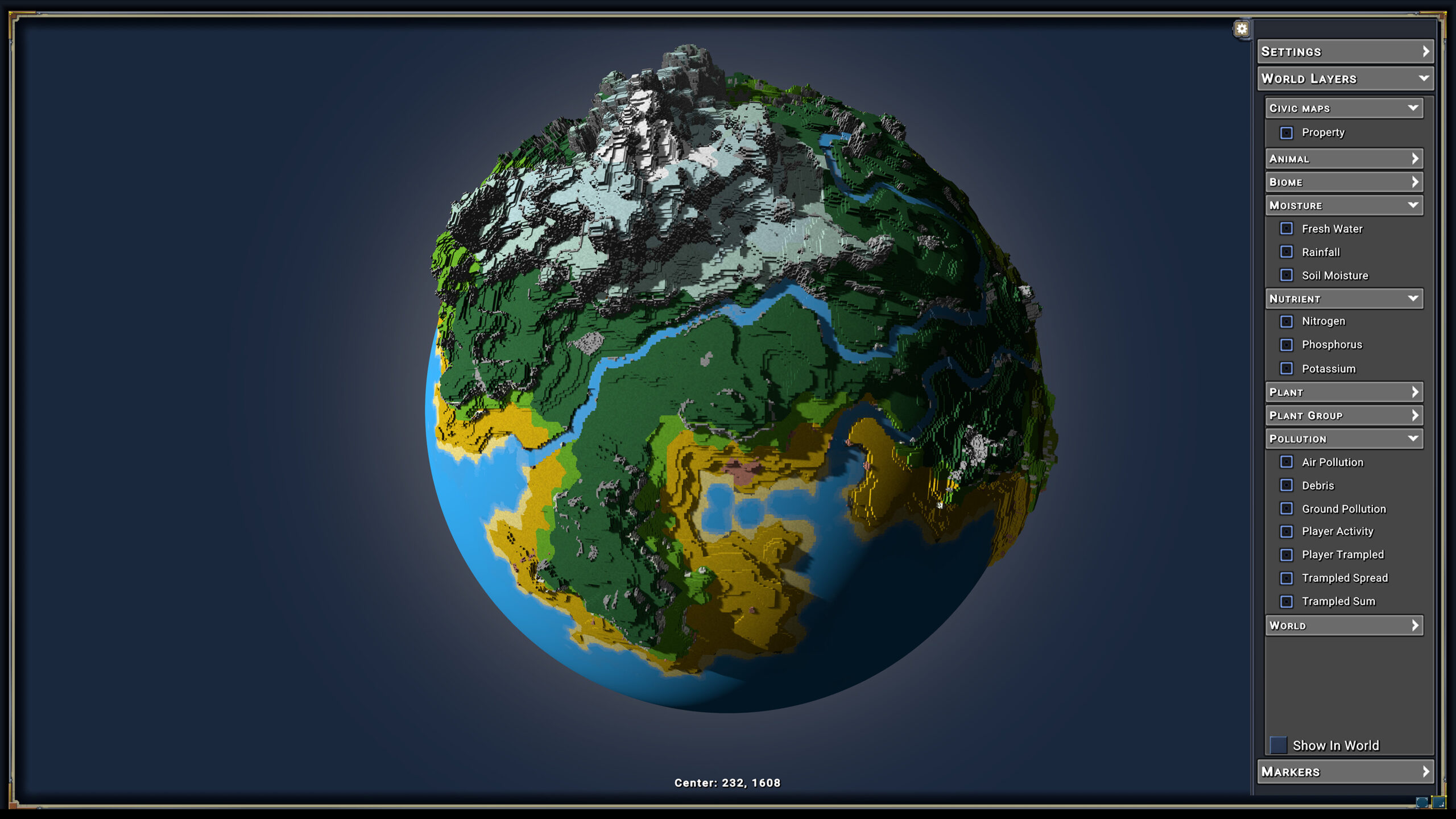

Eco is an online-multiplayer survival-crafting game developed by Strange Loop Games with backing from the US Department of Education. Like Minecraft, perhaps the most famous in this genre, players arrive in an voxel-based, lush, natural world. Armed with nothing but fists, players explore the world, collecting resources and building a homestead. As they advance, more complicated mechanics are available for increased resource collection efficiency and their civilization grows. However, in Eco every action has an ecological reaction. Heavy industries create pollutants; rivers are acidified, flora poisoned, and fauna evicted. Growth, just like the planet, is finite.

As a method for communicating environmental issues associated with climate change, Eco is commendable. The mechanics make visible the effects of climate change at the individual and collective level. Whilst not a direct criticism of the impacts of industrialisation–, it eloquently articulates criticism of industrial development, not through direct rhetoric but through played mechanics. Eco links its simulated model to the realities of climate change is accomplished in just a few short steps:

- To complete the main story, I need to technologically advance

- To advance, I need resources.

- To get resources, I extract them from the world

- As I extract resources, the world becomes less habitable

- I need to be mindful of my patterns of extraction and consumption to complete the main story.

Eco demonstrates how climate change communication can be extended beyond the current paradigm, giving players (and people) the opportunity to understand the underlying causes of climate change and the challenges associated with enacting pro-environmental behaviours. Despite murkiness around the definition of an eco-game, Eco is immediately identifiable as one. It centers environmental issues and gives players tools to understand them at a planetary level. However, are there not opportunities to include slices of these mechanics in a wider range of games? How could the realities of industrial agriculture, e.g.toxic groundwater leaching from chemical fertilisers, be revealed in Stardew Valley? How about the scale of Amazonian deforestation in Green Hell? How would players conceive of this issue if they encounter vast barren wastelands devoid of life stretching towards the horizon?

To answer the initial questions posed, the relation of in-game environments to each other are related by their common abstraction of reality. In addition to the artistic qualities of level design and environmental storytelling, in-game environments offer opportunities to think about environmentalism in an abstracted, narrative-driven manner within the context of an imaginary world. As players accumulate environmental knowledge within these games, their understanding of the natural environment could then be re-applied for tackling problems in reality. Games, unlike literature and film, are interactive. Only through play do we make a game ‘a game’. To advance, information is collected, mechanics tested, and strategies developed. The problem-solving skills that videogames demand offer an opportunity to create billions of potential engaged environmental thinkers but, for the moment, climate change only exists in reality.

If you like what we do here at Uppercut, consider supporting us on Patreon. Supporters at the $5+ tiers get access to written content early.

1 thought on “Planetary Play: Games and the Environment”