Provided by Cellar Door Games

Rogue Legacy 2 and CBT Have More in Common Than You’d Think

I’m not a medical professional. This essay is based on my own experiences and research.

Rogue Legacy 2 is the long-awaited sequel to the popular 2013 roguelite platformer. The game spent two years in early access, with its official release in late April. In the sequel, the Cellar Door team has introduced a ton of approachability and accessibility features that help to support the new game’s sprawling size. They also sanded off a lot of the sharp ableist points that put people off the first game. While Rogue Legacy 2 is much more difficult than the original, it’s also much more thoughtful and approachable — something I learned firsthand by learning to fly.

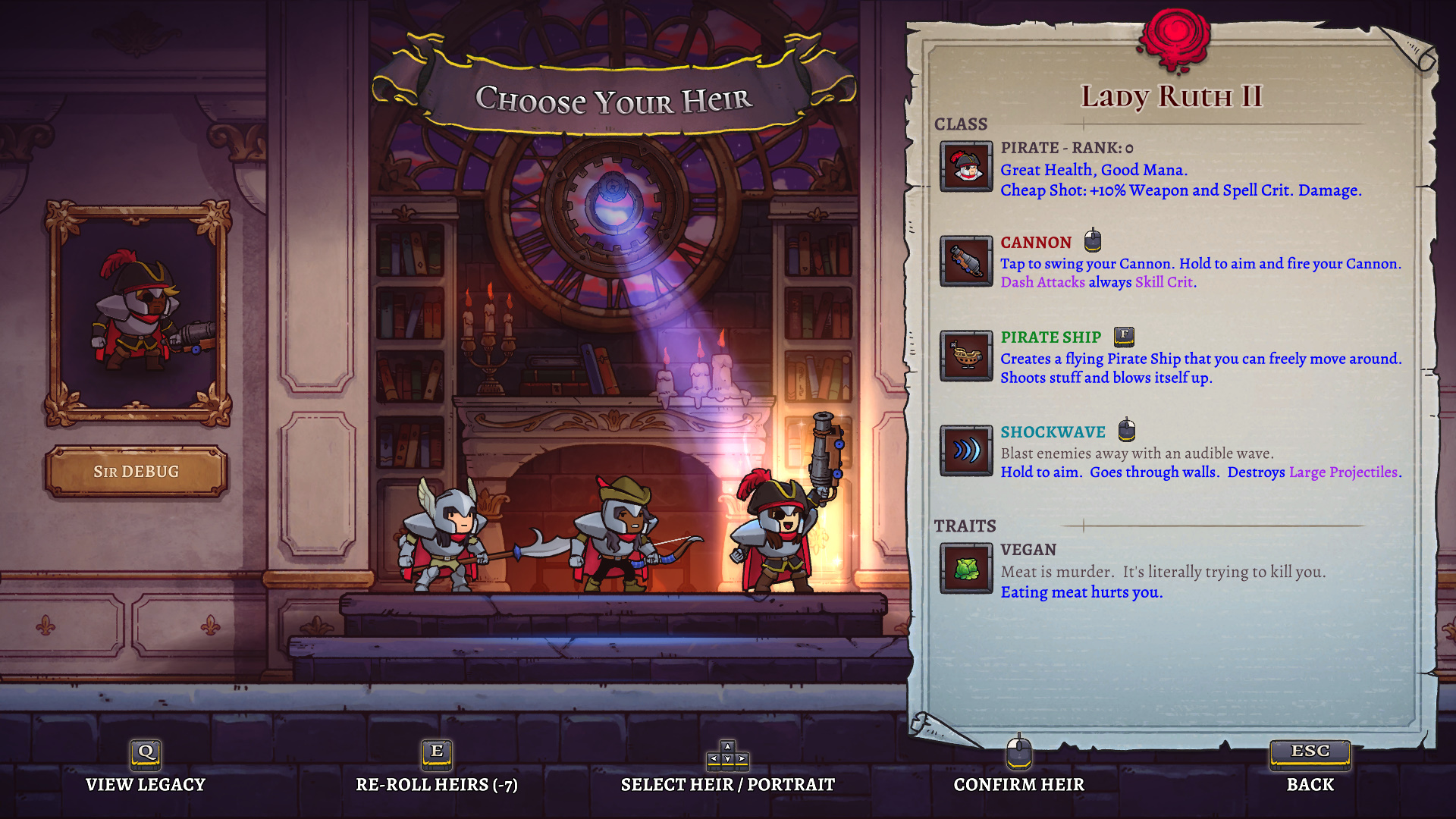

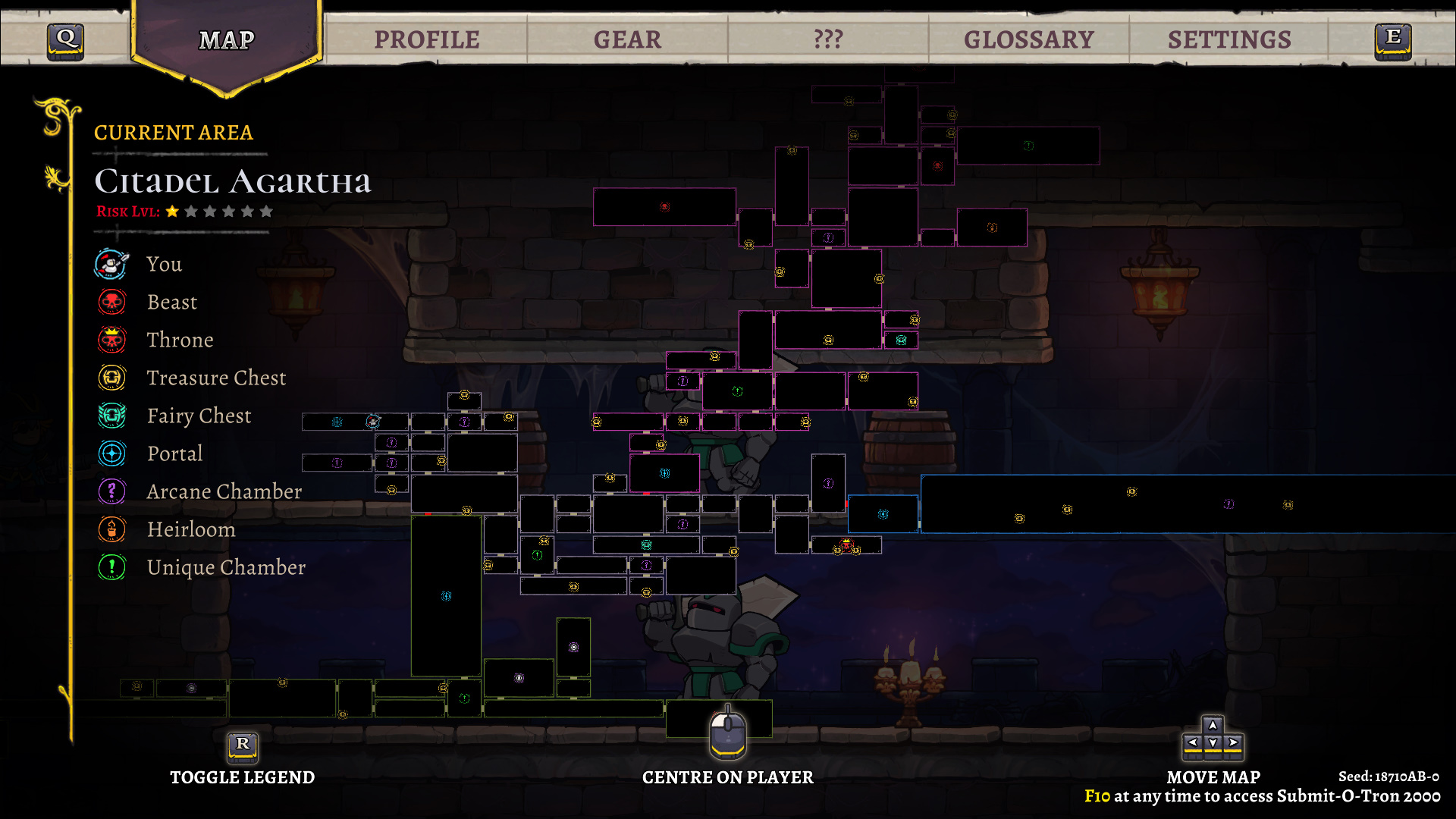

Rogue Legacy has been one of my favorite games for years. You explore a large castle room by room, killing monsters, and beating four regional bosses. Finally, you beat the big bad, realize you were the real danger all along, etc. It’s business as usual for high video game drama. But the game stumbled with some aspects of its core gameplay hook, an inheritance system that wandered into ableist territory using “traits” like OCD, dementia, and ADHD. And it had no approachability or accessibility settings at all. What it did have was, for me, a difficulty curve that I was able to bolster by clawing my way up the elaborate skill tree one upgrade at a time. (I realized while reading Chris Kohler’s great book Final Fantasy V that I love games with leveling up and skill upgrades because they let me take things at my own pace, which is slow, and overlevel in order to make boss fights easier.)

There can be mixed feelings when a game you love gets a sequel, right? The idea of more content is great, but it usually comes with change. My friends know how notoriously I don’t like Risk of Rain 2, a game that turns my beloved 2D pixel-art original into a 3D shooter. If Stardew Valley 2 ever exists, that’s going to be a rough one to get used to. And I ran headfirst into this with Rogue Legacy 2, which finally came out this year after two years of early access. They turned the roguelite platformer of my dreams into something more like Celeste and Dead Cells, with new areas gated behind complicated, difficult platforming interludes and metroidvania artifacts.

I hated it.

After making my way to an interlude section over and over and dying every time, I almost quit. One of the great things about the first game was that it almost never pressed for time — I could step out of a room and catch my breath anytime. Instead, I was facing grueling thirty-second gauntlets of spikes and obstacles with no rest in Rogue Legacy 2. I just can’t do that stuff.

But the sequel makes one huge improvement on the original: there are tons of approachability and accessibility options in this game. You can scale enemy health, strength, “contact damage,” and more. You can toggle on the ability to fly, something that was a gated class ability far into the first game. And at the point where I was ready to walk away, I figured it didn’t hurt anything to switch on the “House Rules” and fly through the interludes – I’d at least get to see the rest of the content in the game, something I’d waited a long time for.

Once flight was on, I flew everywhere. It was so easy to avoid annoying (but doable) platforming moments and areas where I needed to jump carefully. There’s a whole area of the game, the Sun Tower, where I barely toggled flight off the entire time. And all the while, I was doing the same thing as before, clawing my way up the stats in the even bigger skill tree and enjoying the sequel’s far more plentiful equipment drops and runes. I made it through the game, and beat the final boss with just this one House Rule switched on.

Rogue Legacy 2 has one other really big change: it’s a legacy game. Like Hades, this game takes off after your first successful run. So I happily started over, but with all the equipment and upgrades I’d unlocked before, and with a surprising boost to the rewards in every room. And something else funny happened: I turned off flying. With all my leveled up stats, including the critical extra jump, I was able to do almost all the annoying areas where I’d previously just decided to fly. The challenge of them felt interesting and reachable if I concentrated, rather than so tedious that it could never be worth it.

This is when I started to realize how the game was working for me. The familiar parts, like the platforming combat, still felt right for my level of experience. The new parts, which I bristled at, just called for a little bit more support in order for me to get used to them and start to enjoy them. I had to be able to reasonably close the gap between where my skills were and what the game was asking of me, which meant sometimes lowering the difficulty so it was within my reach.

Somewhere deep in my brain, a little bell was ringing. It took me a while to figure out why all of this was feeling familiar somehow. One day, while playing, I thought, “People need goals.” It’s the name of my friend Jack’s music project, but it’s also one of the cornerstone concepts of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). CBT is a popular therapeutic approach that uses goals to help people identify and regulate their own emotions better, helping to alleviate anxiety and depression symptoms.

In a 2013 paper for the journal InnovAiT, two researchers explain the foundations of CBT and how it’s ideally supposed to work. “CBT ultimately aims to teach patients to be their own therapist, by helping them to understand their current ways of thinking and behaving, and by equipping them with the tools to change their maladaptive cognitive and behavioural patterns,” they explain. In other words, CBT tries to laser focus on your deepest, darkest beliefs about yourself in order to identify how you have learned to cope — and then ripples out into changing your behaviors.

To do this, CBT uses a model called SMART: setting goals that are “specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and time-limited.” My own therapist first drew my attention by discussing their incremental approach, something that appeals to me as I keep learning to live with my anxiety. And this is how Rogue Legacy 2 grabbed and finally held my attention: by allowing me to adjust the gameplay to support my one missing piece, and let my skills level up until I was able to do it mostly on my own.

There’s honestly a lot more that I could say about the game. It’s beautiful, with richer art and more scenic vistas than the original. There is a cast of characters who all offer helpful, thoughtful feedback. The game’s new artifact system focuses on building capability and toughness, similar to the goals of CBT. And one of the surprising new features, a system of “scars” where you fight specially prepared battles, is all based on the idea of generational and emotional trauma — something that the game’s original premise, of a doomed, cyclical line of descendants, really lends itself to.

But for me, the key piece is still that the game made itself approachable for me. After that very first run, I’ve barely used flying at all. There’s one sticky place where I still have to use it, because I can’t climb the wall of buzzsaws and I’ve accepted that I will never be able to. The rest of the time, including with the bosses, I can handle myself and take the game on with the right combination of underlying skill stats and the class features of different runs. All it took was a little bit of a running head start, and some realistic goal-setting.

If you like what we do here at Uppercut, consider supporting us on Patreon. Supporters at the $5+ tiers get access to written content early.

1 thought on “Rogue Legacy 2 and CBT Have More in Common Than You’d Think”