Provided by Raw Fury

Sable: Small Stories, Epic Scales

To Lotus,

Games very rarely feel like they’re about real life – even when they’re set on Earth and have millions of dollars worth of pixels trying to convince me of their veracity. So often they don’t feel real. Many larger games have world-ending calamities or enough bloodshed to fill buckets, all in an effort to make me care. But what are most of them saying about real life, the lives that most of us live?

Sable feels decidedly different in this respect. It takes a moment in life that would seem mundane in any other game and makes it feel as monumental as it should: the moment you move away from home. Sable, the titular character not the game, and her coming-of-age story echoes the feelings that accompany flying away from the nest.

Her flight away from her nomadic clan mirrored my recent experiences. She leaves to find masks that’ll decide what she does with the rest of her life. Does she want to be a Machinist or a Cartographer? A Warrior or an Entertainer? It reminded me of my own experience of moving away to University, deciding what kind of person I want to be, trying on different faces for different people.

When I first played Sable I was slightly bothered by the fact that she’ll need to wear the mask she chooses forever. What if she’s tired of entertaining by 50? Why does she need to pick so young? For me, it was at odds with the real life allegory I had built in my head. I told myself that’s not the way it works in real life, you can be anything you want at any point. But it slowly dawned on me that maybe that is how it works in real life. At least in British education, students are made to limit and specialize on subjects from a young age without the life experience that’s necessary to know what you actually want to do. Meanwhile, in the world of Midden, young people are allowed to go off and see the world, trying out different professions before committing.

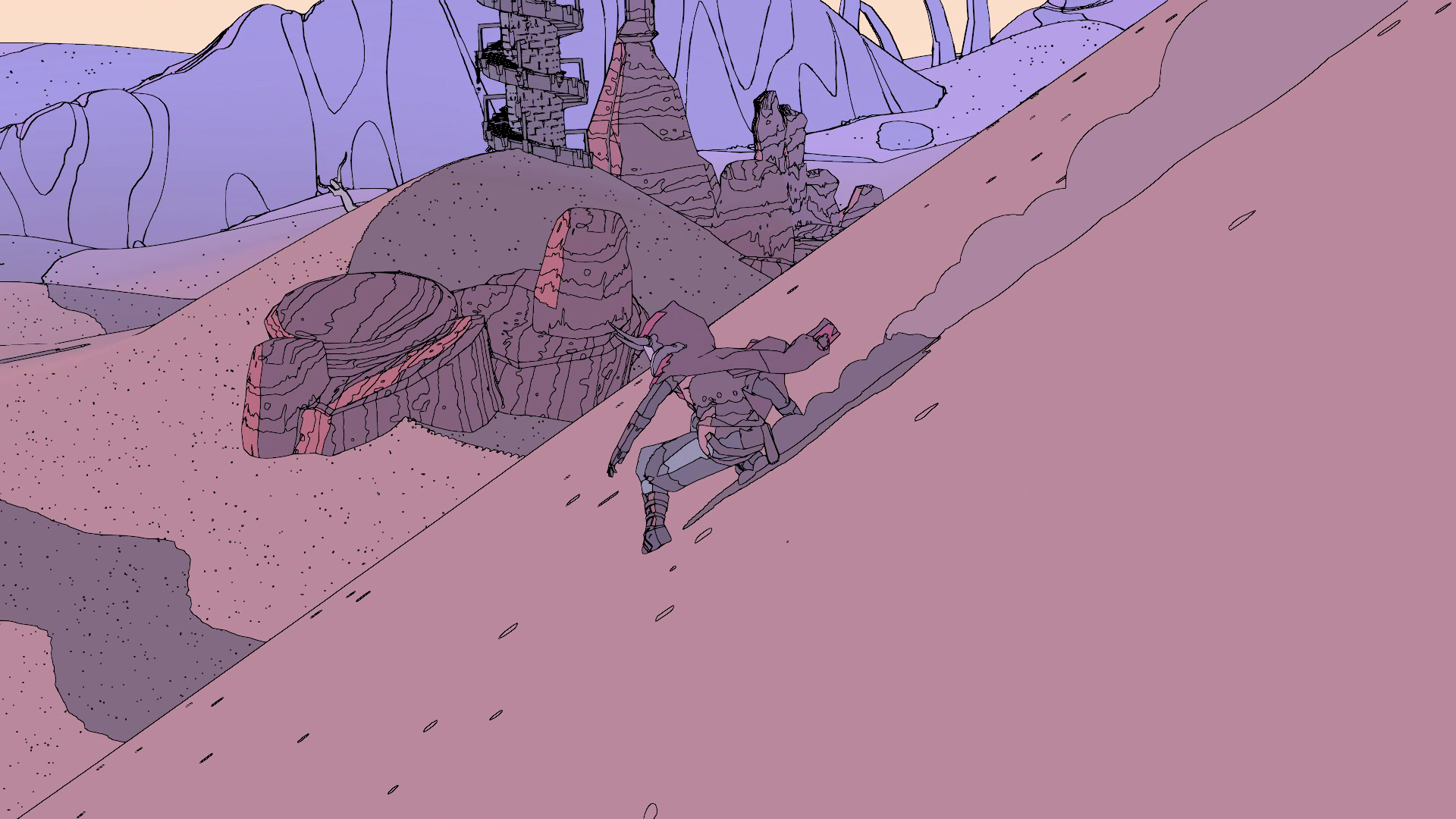

The best thing about her coming-of-age journey is the freedom it gave me, it left me to my own devices completely. The minute I left the tutorial area the entire map opened up to vast dunes, skeletal graveyards, ancient ruins and solemn shipwrecks. I was free to journey anywhere with an open-eye for points of interest or people to talk to. There were no waypoints or arrows pointing toward the next badge – so the crippling responsibility to decide who Sable should be (or who I should be) was on me. Just like real life, this open-ended freedom can become overwhelming. Where do I go? Did I miss something? Can my parents come and decide for me?

This anxiety is alleviated through Sable’s epic presentation. The world of Midden frames mundane human moments like they’re epic affairs. Saving someone from the bottom of a well saw me climb down a series of crumbled stairs and vines growing out of the uneasy structure. Collecting a lightning stone had me scaling a number of gargantuan statues, waiting for lightning to strike. It feels like games about the domestic, about the small, intimate moments, usually come in smaller packages like Unpacking or Florence. Developer Shedworks rejects this; Sable’s a game about growing up, set in a world full of fantastical sights. Sable understands that there’s a gravity in even the most mundane moments in life and as a result every dilemma in Midden is given the grandeur of a Lord of the RIngs film.

For example, one quest had me track a legendary poet across the map until I found her in a cave on the side of a mountain. After having a surprisingly introspective chat about the meaning of life, I left the cave and on the horizon laid countless airships that were half submerged in the sand, their carcasses spread out over the white desert. Questions about how to live my life and who to live it for were still fresh in my mind, and now I had a graveyard holding a mirror at me. It was both a haunting reminder of how fickle life is, but also a push to live it to the fullest regardless. Personal contemplation had taken on epic proportions through Sable’s environment and this was neither the first nor the last time it had happened.

Sable’s relative emptiness and vast horizons recalls Shadow of the Colossus, it’s designed to leave space for introspection. Rather than exploring to advance the game, in search of better gear and loot, exploring Midden is more about opening yourself up to the world.

Sable’s pilgrimage isn’t just about finding out who she wants to be but it’s about how she’s situated in this world. The open-world of Midden is bustling with nuggets of information about Midden’s culture, customs, history, beliefs, astrology, traditions. From its bustling merchant’s city to the skeleton of monsters, every inch of Midden is contributing to world-building. It very much feels like going away from home and seeing the world for yourself. Talking to the citizens of Midden is always a joy but this is probably because of the attention to detail put into every single encounter. The world of Midden isn’t a disposable space stuffed with filler content and a million forgettable side quests – everything that is here had a lot of TLC put into it.

I find it kind of funny. When I first played Sable I enjoyed it. But, slowly, I’ve appreciated how special the game is. It’s a game that quietly grows in stature. In fact, it’s a quiet game in general. It’s one of the few open-world games that give the player the time to think about the place they’re moving through, to think about what’s going on and how they can relate – despite the fantastical, alien world. It’s a game that’s so sincere, and honest and universally recognizable, it’s just a shame that the experiences on display aren’t given the same level of respect in other titles.