Soundscapes As Stories: How Games Are Changing How We Experience Music

Before I bought my first used iPod, and listening to music became a mess of stray MP3s and burnt mix CDs, an album was a ritual. I’d save up, take a walk, and flick through CD cases at the shop for a half hour. When I eventually made a choice and brought it home, I’d lie on my bed, eyes closed, and listen to the whole thing. Not as the background noise to another activity, but as a sole focus. The reward for my undivided attention was the feeling of being present within a soundscape from start to finish. The difference between a journey and a visit.

The economic and social pressures to manage our time with an almost mechanical efficiency increasingly encourages us to experience art in chimeric form – so much art, so little time. Streaming services like Spotify offer convenience, but they also remove individual tracks from their original context, muddying intent and emotion. If we look at albums as sonic stories, then the last fifteen minutes of a forty-five minute LP is the third act. A playlist, in contrast, becomes a collection of disparate scenes.

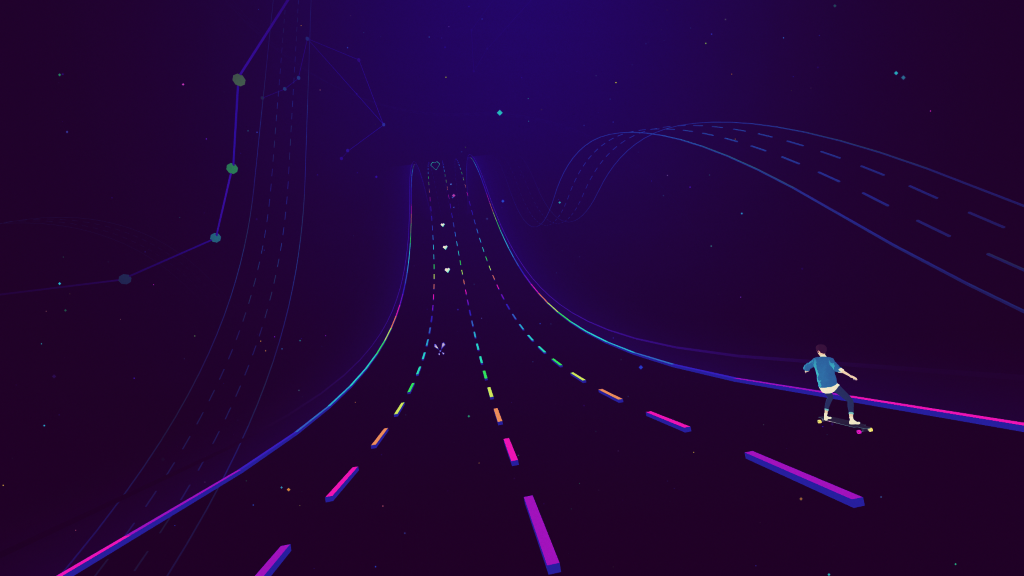

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that Sayonara Wild Hearts—billed as a “Pop Album Video Game”—is the closest thing I’ve had to those older experiences in years. It’s an album that let me live inside of it, fly with its highs and plummet with its lows. Travelling from level one to credits, and from the opening track to denouement. It felt like a way to breathe new life into a form buried under busy lives and fragmented listening patterns. Story, haptics, and sound intertwined.

“Sayonara asks players to experience a journey similar to an album. It’s a narrative that’s been meticulously planned to deliver an emotional experience,” Daniel Olsén, the composer for Sayonara Wild Hearts, told me over email.

Simogo’s Sayonara Wild Hearts, if you’ve yet to experience it, is something akin to wandering through a forest of dry ice and lasers at a music festival, and stumbling through the screen of an enchanted arcade cabinet—a transcendent rhythm-runner scored with glittering, lovelorn synth-pop.

Each level is presented – both through menus and as a step in an emotional, sonic journey – as an album track. As you sprint, slide, and swerve protagonist Claire de Lune from the broken hearts of “Begin Again” to the butterflies of “Wild Hearts Never Die,” your fluttering thumbs join her on a journey brought to life through a synthesis of music, visuals, and level design. Though it’s the music that carries you, it’s the journey that’s key.

Could Sayonara Wild Hearts—and games like it—be a whole new way to present the album?

As a composer of both music and game soundtracks, Olsén compares games to concept albums, where similar restrictions apply.

“When you write an album you’re completely free to just make up whatever you feel like at the moment—if it sounds nice, then you’re good. With games, you also constantly think about mood and pacing, because the experience is not just the music alone. If it doesn’t feel natural when you play, you have to change things until it works, or start over.”

Getting to the point where Simogo felt like they’d achieved the synthesis required for this journey, Olsén said, took a lot of work. “Things like buildup, pacing, melodies, that would normally work for a song oftentimes wouldn’t work at all when we put it in the game,” he said. Levels would evolve, get scrapped, redone, and with them, the music would need to change.

“At various points in development I had to maybe shorten songs to a third of the length, or add a buildup and drop for a specific sequence, or change the music into a climax, or add a different section.”

Despite the painstaking iteration this required, the flow of work followed a “deceptively simple formula” Olsén said.

“Level changes to fit music, music changes to fit level, repeat.”

Before Sayonara Wild Hearts, Olsén had worked with developer Simogo on several projects, like the haunting Swedish folk tale Year Walk and text adventure Device 6. They all started the same way: mood boards, concept discussion, then collaborative Spotify playlists.

“As the concept evolves, songs are added to the playlist which serve as inspiration for music, instruments, feel, or whatever is relevant for the project.”

“At the beginning of Sayonara we had a totally different, much darker direction for the music, so we had to start over with a new playlist when we changed into more of a pop direction. Pretty early on there were animation tests, videos and playable sections of the game available also, so I had plenty of material to work with.”

The major hooks, Olsén said, were in place early on.

“The game starts with ‘Clair de Lune’ and then towards the end there’s a dip in pace, before the final levels. Simon [Flesser, the ‘Sim’ in Simogo] had those planned, so he would ask for certain types of songs to fit sections like that.”

Despite these set points, the project stayed mainly dynamic. Some of the destinations were planned, but the journey was left open.

“It grows, it changes, it has a life of its own, and this game is a great example of that,” Olsén said.

The audio mix between ambient sounds, sound effects, and instrumentation add another layer of complexity. Once all the elements come together, scoring Claire de Lune’s story from start to finish, the dual aspects of Sayonara Wild Heart’s story take shape.

Olsén told me how one of his favorite aspects of the game—which is also one of the complaints he hears from players—is the short levels.

“You’re just getting into the music when the songs end, but it creates a build-up of emotions. When the final stage comes and goes on for almost 10 minutes, it’s such a release of those feelings, it’s cathartic—like listening to the last track of an album, one that forces you to reorient yourself.”

Olsén believes that interactivity—and reactivity—gives players a special connection to the music.

“It’s like you’re doing your own performance to the music, and you can appreciate the nuances of the narrative and sound coming together. In general when you hear a song that really moves you, you want to be involved with it: singing, dancing, simply tapping your foot along to the music. Sayonara is extra satisfying in that not only are you able to interact with the songs throughout the game, but the narrative can’t move forward unless you do.”

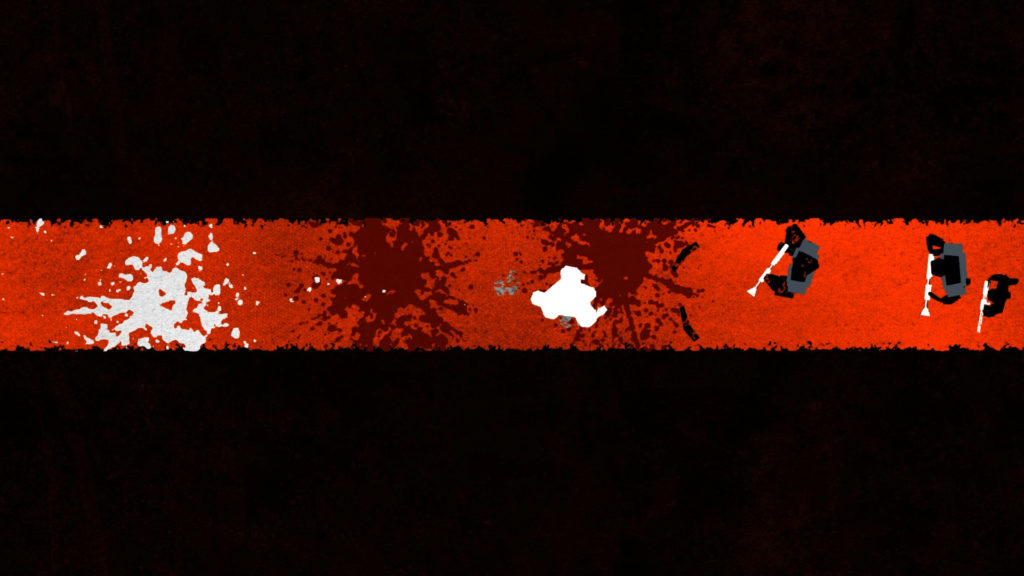

Last year’s Ape Out, with its reactive percussion and stages arranged as LP tracks and sides, may be less curated than Sayonara Wild Hearts, but the music is no less vital to the experience of playing. Despite a simple set-up (what if Ape, but Out?), the soundscape was designed with another type of journey in mind—that from repeated player deaths to mastery.

Ape Out uses what composer Matt Boch described as “procedural compositional patches”—sets of percussion samples that trigger when the player performs certain actions, like punching armed guards into concrete walls. The size of these patches, Boch told me, depends on roughly how long himself and developer Gabe Cuzzillo imagined players spending on any one level—and how often they’d be dying.

“The opening kit is by far the largest and most diverse, as we expect lots of deaths early on,” Boch said. “It also comes back in the [bonus level] single, which is tough as nails, so I knew that patch had to be among the strongest.”

Beyond this, Boch said he tried to minimize specific compositions and set pieces.

“The intention behind the system is for it to feel improvisational all the time. The only true compositions in the game are the credits music and the level intro sequences.”

Much like Sayonara Wild Hearts, Ape Out’s harmonizing music and play was an iterative, collaborative process between Boch, Cuzzillo, and Bennett Foddy’s art. Along with a demo of the opening level, Cuzzilo created three drum styles: a classic swing jazz set to establish a tone for basic play, a bebop set for stealth, and congas for an early sequence where an alarm is set during our ape’s escape. Boch would flesh these out into patches, and the team would test and iterate.

“As with many games,” Boch said, “it wasn’t until the middle of development when we all really understood what we were making.”

Where Sayonara Wild Hearts invites us to play along with Claire de Lune’s story, the highs and lows of her journey spaced out over 20 or so tracks, Ape Out’s procedural pockets of sound are given direction through the intensity dictated by level design. Ape Out is a collection of album sides in aesthetics, while Simogo’s game is an album in terms of the cohesive experience it offers the player.

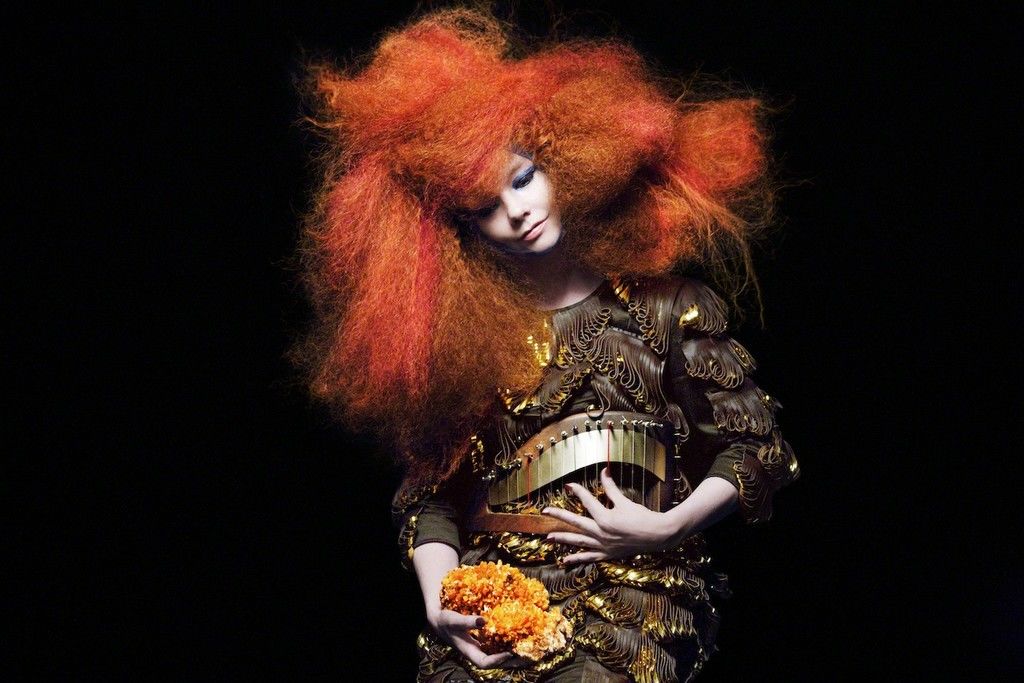

Back near the beginning of the decade, singer, and accidental ASMR pioneer Björk released the album Biophilia and, alongside it, a multimedia project including an iOS app. The app featured a simplified sequencer and several games complimented by certain tracks. Writing for the New York Times in 2011, Seth Schiesel said, of Biophilia’s impact on culture, “The real music revolution may just be beginning: a revolution that changes the substance and practice of loving music.”

Though in-game concerts—like Travis Scott’s recent Fornite appearance—and apps like Oculus’ Wave VR are offering a fusion of digital and live music experiences, projects like Sayonara Wild Hearts still remain few and far between. Olsén told me that, while he’d love to see more games that intersect with albums in this way, he feels the work involved would be too prohibitive for it to become a regular occurence.

“For an album, I feel like most musicians just want to focus on the music. To add a game on top of that, there’s a whole other realm of things to worry about”

Though they may offer the most obvious overlap, narrative journeys aren’t the only way games and albums intersect, either. Even in digital form, games offer something that’s often attributed to the resurgence of vinyl in the music space: touch. There’s a language crossover here between academics, artists, and critics working in both games and music; words like “haptics” and “kinesthetics” apply to both spaces. While it’s only the rare project like Biophilia where these terms apply in the sense of “game feel,” there’s another area that both mediums share where they harmonise: the collection of tangible media.

“As a physical collector, there is definitely a ritual,” Limited Run Games co-founder Douglas Bogart told me. “I enjoy tearing up that shrinkwrap and the smell of opening that case. I know it’s weird, but I don’t know, it just brings me back to being a kid.”

Founded in 2015, Limited Run Games are a distributor focused on putting out physical copies of digital only, or retro, titles. Often shipped with custom art and add-ons, they offer something tangible for collectors who want to see their favourite games on their shelf, not just in a digital storefront.

Bogart said that himself, co-founder Josh Fairhurst, and art director Shadie El-Haddad, are all big record collectors, and that the link between vinyl and physical games is something they all share. “Once digital music became the norm people started realizing they missed physically owning the actual music. It’s a more intimate experience to take a vinyl out and listen to it versus just hitting play on an app.”

Bogart attributes the resurgence of physical games to a few different factors, one of which is an older audience that grew up, like himself, unwrapping plastic and reading manuals, now with disposable income and a yen to recapture that experience.

“I also think people are starting to finally see the downside to digital with the closure of digital storefronts,” Bogart added. “The Wii Shop Channel is gone now and so are all those games unless you had them downloaded. It’s the first major storefront to be closed and the effects are being seen.”

When Limited Run started in 2015, they sold mostly to older customers, but Bogart said he’s seen more of the younger demographic—digital natives, without the same direct nostalgia for boxed games—get into collecting in recent years.

“Now that YouTubers are doing videos on game collecting, their younger fans are getting into collecting themselves! It’s a nice mix now for us and we seem to have fans of all ages,” Bogart said. “I still see plenty of kids come into game stores buying physical games and maybe that is just the parents being more familiar with the concept, but it’s nice to see physical is still going strong.”

Neither is the rise of digital as all-encompassing as it can sometimes seem. In 2017, Japan’s physical music sales accounted for 72 percent of the market. Similarly, according to a 2018 Famitsu report, the sales of physical games eclipsed digital in the country. The second best selling game of the year—Super Smash Bros. Ultimate—sold over 2.3 million physical copies, compared to just over 310,000 in digital. In a Q1 2019 breakdown of European games sales, GamesIndustry.biz listed anywhere from 66 percent digital sales in the Nordics, to as low to 33 percent in Italy. Although the report pegged the U.K. at 56 percent as of 2019, the actual profits from digital versus physical sales have been reported elsewhere at as high as 80 percent.

In “To Have and to Hold: Touch and the Vinyl Resurgence,” University of London musicology professor Adam Harper offers a series of counterpoints to the claim that vinyl records “be considered exclusively or supremely tactile among recorded media.” Among Harper’s arguments are that MP3s still represent material objects, albeit with an imperceptible scale, and that both the MP3 players and computer keyboards we use to interact with digital music offer their own sort of tactility.

“It is not that audio experienced through mp3 or streaming services is not ‘real,’” writes Harper, just that it is “manipulated as a virtual object in a virtual space, one not all that unlike the virtual space of the stave and the notated objects that inhabit it, or indeed that of a musical performance (re)constructed in the imagination during listening itself.”

Similarly, we might argue that digital games still offer the experience of tactility, just through Joy-Cons, Wiimotes, or Razer mice. We can touch a game without ever holding it. Still, with games like Sayonara Wild Hearts and Ape Out, the tactile experience of engaging with the composition and intent of the soundtrack is given a whole new haptic layer—and perhaps a whole new sense of history.

“Vinyl’s physicality and tactility is part of the fight against encroaching virtuality—note the simultaneously literal and metaphorical meanings of ‘hold onto something,’” Harper writes.

This sense of “holding onto something” is nowhere more prevalent in the gaming space than with retro enthusiasts, where the use of CRT monitors, RGB cables, and original controllers are popular because they all contribute to the experience intended during development. Similarly, the sound chips in original hardware are often difficult, or impossible, to emulate correctly.

“It is very like audio processing in that having an analog stage really helps breathe in life, warmth and imperfection, even if that’s an RGB cable going to a digital upscaler vs a full blown CRT setup,” Jasper Byrne of Super Flat Games told me. “Each machine has its own flavor in the way it converts its image to analog, just like each sound chip (and extra the ones in some carts) have their own unique (non-emulatable) properties.”

It’s easier said than done—although no less fun—to speculate about haptics, sound, visuals, and narrative might merge together in games for the future. Will it be through fanmade, curated concept albums for Beat Saber, or through games like Thumper or Wipeout? Whether we’ll soon see more projects like Sayonara Wild Hearts, that pair albums with games so that each is inexorable from the other, is uncertain.

But just like those old CDs, it’s a journey I’d love to take again.

1 thought on “Soundscapes As Stories: How Games Are Changing How We Experience Music”