Spirits in a Material World: The Touch of Clubhouse Games

The first thing that struck me about Clubhouse Games is how physical it is. Though it is entirely digital recreations of board games, it resists abstraction. Cards hit on wooden tables. Games take place on kitchen tables or bizarre pastiches of casino card tables. Even its simple recreations of baseball or tennis are depicted as elaborate toys, the kind of thing one could imagine a rich friend having. It’s easy to write this off, of course. The slap of a card, the clink of a tile, the knock of a piece on wood are all part of a language of satisfying, responsive play. Any faithful translation of those games would require some acknowledgement of those sounds and actions.

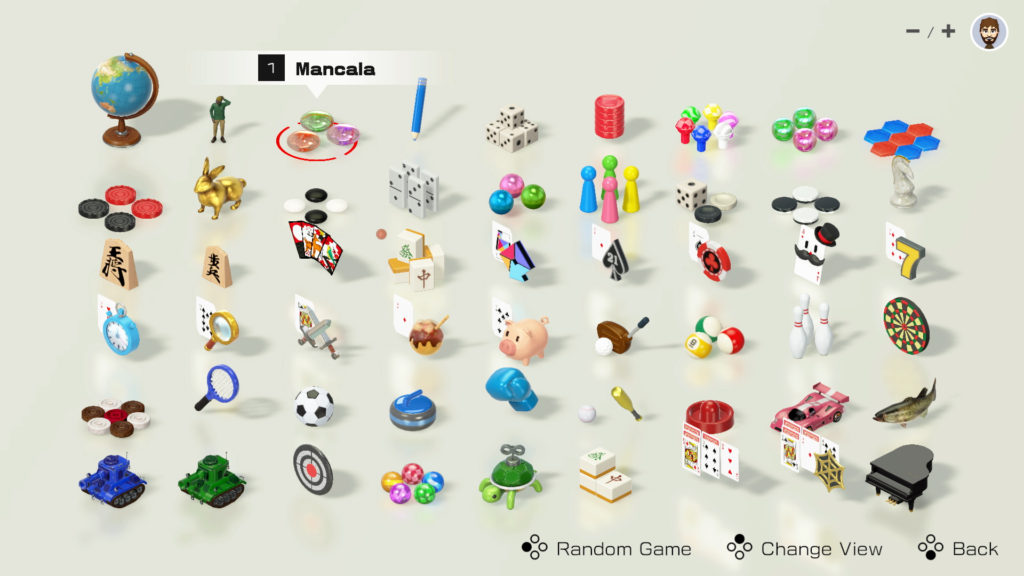

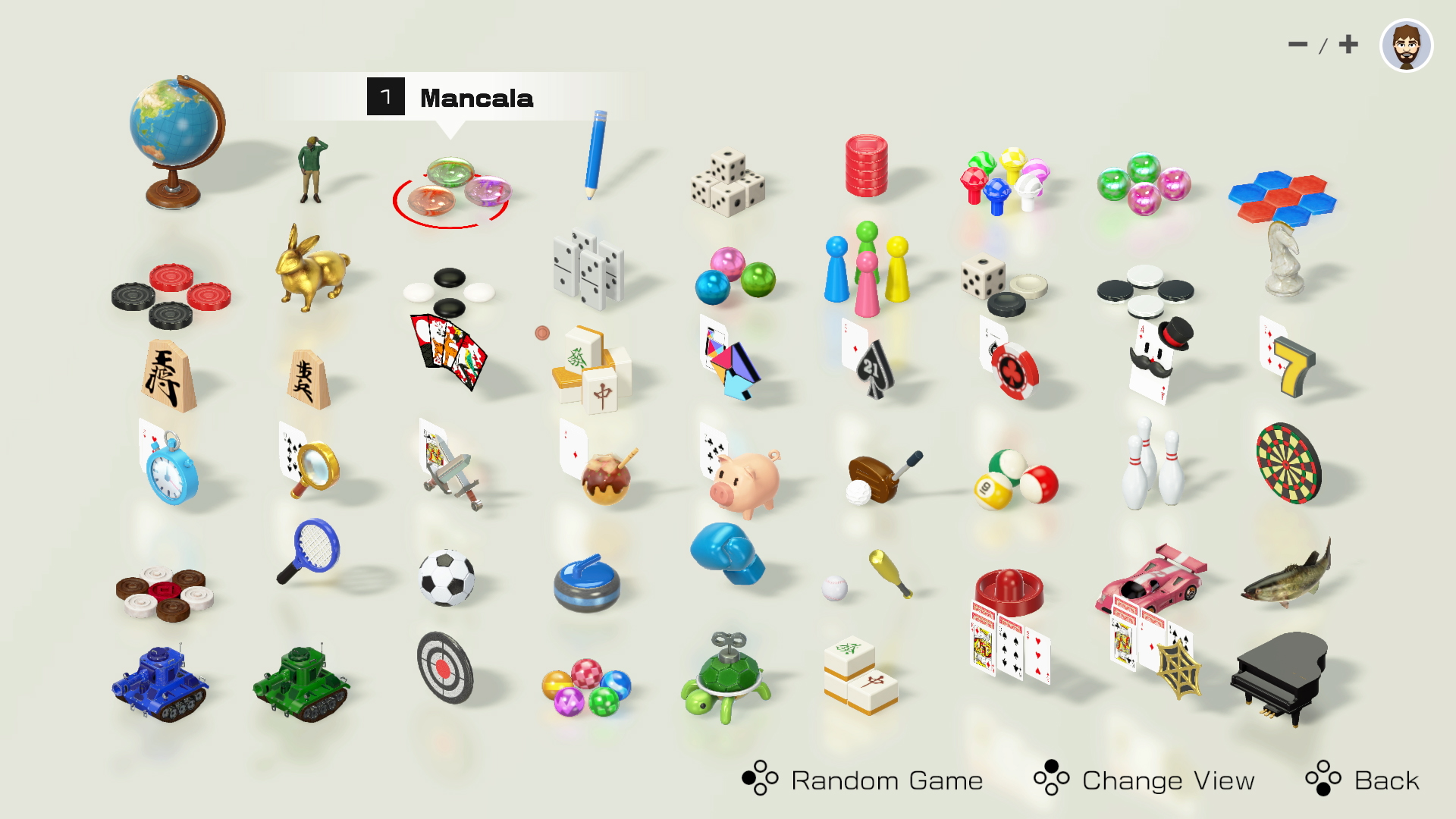

Still, the settings of these games have a more immediate sense of place. Every game has its own table setting, sometimes literally. Mancala is set on a little table rug. Coffee mugs are set around different parts of the slot car track. There are a few exceptions, like fishing or golf, but most games are set on a hardwood floor or a warm wood dining table. The game sets a scene beyond the satisfaction of moment to moment play.

This extends even to a loose community. At the beginning of the game, you choose and customize one of a number of figurines. Even the computer opponents are given the barest sense of self. For example, one is an older woman with grey hair and cat eye glasses. Another is a young man with black hair. They are only silhouettes, suggestions of a wider community. The people who introduce each game to the player are a little family, each represented by figurines similar to your own. At each step, the game foregrounds that there are other people playing, communities set and built around these games.

It would be, so easy, to write about Clubhouse Games as a salve for the loss of touch. I felt that essay tingling on my fingertips. It was, I will admit, nice to pretend I existed in a real social space. However, we are going to get so many pieces about the loneliness of quarantine or the terror of existing in public spaces. However, we are all going through these things. I don’t know what navel-gazing does other than, at best, offer weary recognition and at worst, cheapen or demean other people’s pain.

So instead, I would rather confirm that games are real means of connection. There’s been a lot of writing, even more recently, about games as a reprieve. The peak of this was back in March, with Animal Crossing New Horizon’s release. But games like Spiritfarer, or even Hades have had their moments. There was even a whole press conference about “wholesome games.” For many of us, games are something that can sand off the hard edges of life. Something that detaches us from the world, if only for a moment.

But, as we use games to escape, they do work. The work they do is often very very bad for people and the planet. Even Animal Crossing has become a site of political battlegrounds, where black identity is contested and asserted. Cyberpunk 2077 triggers epileptic seizures. For the eyes it has not cared for, it can harm or kill. For everyone, but especially those of marginalized identities, games cannot be an escape. They are again sites of conflict, of selfhood, of class, and of negotiation.

That is a truth both terrible and affirming. The material that makes consoles must be mined, stolen from earth at great cost. Those materials then tremble under my fingertips or hum next to my television. When I clash fists in Skullgirls with friends across time zones and oceans, or when I steal a star from my brother in Mario Party, I press plastic to send electricity across circuits, across power lines, across airwaves. That is a real kind of touch. Clubhouse Games only leans into those truths. It is nowhere close to radical, but it is refreshing to play something that is so grounded in the material. Clubhouse Games does not offer an escape. Instead, more truthfully, it offers an extension. Games to play with other people, who exist, given points on a map, putting hands to controllers just like mine.

Critics, even those vowed to know better, so often forget that games are material things. Putting a disc into a drive or even downloading through a storefront, requires passing, touching so many hands. The keyboard clacks of every programmer, the pen strokes of every artist, the sweat of every warehouse worker or miner, a game is all of those things. In this new year, I hope we carry forth the beauty and the terror of that truth. I want us to work to destroy games as they are, so that a sustainable, better future can bloom. To do so, forces us to place seeds in the earth, to get dirty. We cannot claim detachment or escape anymore. To write ourselves into the world, we have to know the real and believe that it can change.