Image Source: Nintendo

Splatoon 3: THE GIRL FROM INKOPOLIS

Snow has fallen on Albert’s Forest.

The coating is pristine, as though it lay atop a royal wedding cake. Its decorators have not missed a single spot;: man-made structures are finally embraced in their new form, and even the sparse evergreen trees are offered a winter makeover. Without leaves forming dense trench coats, the other trees lack their usual huddled mystique; suddenly the area feels honest, welcoming, whimsical. It is as though the forest has been child-proofed: every sharp edge has been smothered by this great blanket, while the only rogue shapes – those naked branches – hoist themselves safe from reach. Imagined families of woodland creatures gather doll-like around dinner tables, their snug homes appearing only as tree trunks and burrows to the naked eye. The wind holds its breath so as not to ruin the moment. On cue, our narrator enters the scene, and makes his way across a thin wooden bridge. He has a strange story to share with us.

“I found out that when you walk on the snow, it leaves footprints,” he begins, “and if there are footprints, it can tell you if something has been there.” His voice is jovial, and his bouncy gait even more so. A distant vibraphone seems to egg him on; we, the viewers, do the same. Reaching the end of the bridge, he suddenly finds himself confronted by a great crater in the snow. He cries out with pantomime zeal.

“Ah, footprints! Has something been here?”

Our minds rush to dinosaurs and kaiju and abominable snowmen. In their place, however, the footprint itself begins to speak. Its voice is aged yet bright.

“What does it look like, silly fellow?”

* * *

Splatoon 3 treasures our world, and our world its own.

From its first reveal in 2014, Splatoon emerged as a complete thought, an unimpeachable abstraction of teenage rebellion into game design. The years since have welcomed a new wave of exciting, expressive shooters – DOOM, Titanfall 2, Neon White, ULTRAKILL – yet there is still nothing like Splatoon, a safety net that has allowed Nintendo to explore yet-deeper cultural spaces with each successive entry. After three games, we look at Splatoon not as a colourful outlier within the shooter genre but a series of bizarre aesthetic experiments, and as such it no longer feels pertinent that we pull apart its mechanics; rather, this is a third opportunity to gaze upon this landfill dreamland, and to see which human trinkets have influenced its creators.

Marine society has evolved greatly in our absence, and chaos has become its dominant cultural force. Now taking place in the apocalyptic “Splatlands,” the main competitive mode has fully embraced punk stylings: characters string makeshift swords and bows over tattered shirts, and enter battle using launchpads fastened from washing machines. The co-operative “Salmon Run” is somehow even more nightmarish than before, capitalist satire giving way to rotting dread as we question Mr. Grizz’ higher purpose. Splatfests return as technicolour wonders, their electric atmosphere drawing from the Brazilian carnival influences of leading act Deep Cut. Inklings can now dab after matches. The surface remains a place of fresh energy and change; its most captivating sights and sounds, however, lie underground.

Beneath the vibrant city, beneath great valleys and abyssal canyons, beneath even the shady subway lines of the previous game, Splatoon 3 takes us to Alterna, a vast dome hidden at the centre of the Earth, and a cultural soup from which this new society dredges its treasures. From the snow-covered islands of this great lake, vestiges of humanity peek out, glimmering in the artificial sunlight: Moai statues stand in proud lines, while hidden documents reveal streetwear and comic strips. At the lake’s centre, a rocket stands fearless, the spiny tendrils of a yet-unknown disease wrapping around its base. Holographic blue skies try and fail to perfect the scene. Alterna is scattered; ethereal; dense with history.

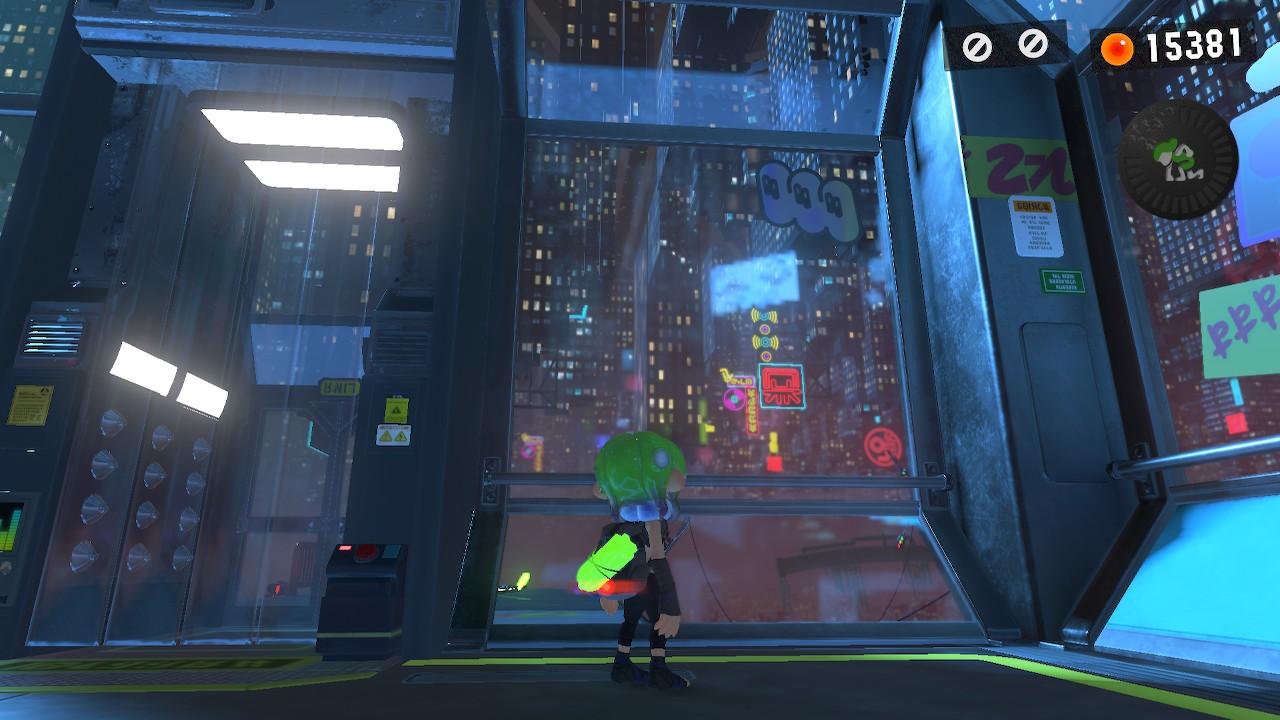

Alterna’s action stages, too, feel as though assembled from human parts. Nintendo has long been praised for its artisanal approach to level design, but the story mode of Splatoon 3 applies this wizard’s-laboratory process to its aesthetics: every stage is framed as an experiment – each with its own decontamination room and science textbook-ish title to match – and all paint vast skyboxes of captivating disarray. One stage invites us to grind rails between sea and sky, a carpet of skyscrapers looming hazy in the water. Another imagines the computer as creator of a pocket universe, error messages floating among the stars. The soundscapes of these environments are themselves a microcosm of the game’s cultural cauldron: vivid and viscous, these songs take human inspirations (Midori, Mouse on the Keys, Hakushi Hasegawa) and blend them so lavishly and lovingly that they become something unrecognizable, all while carrying the passion of their original composers.

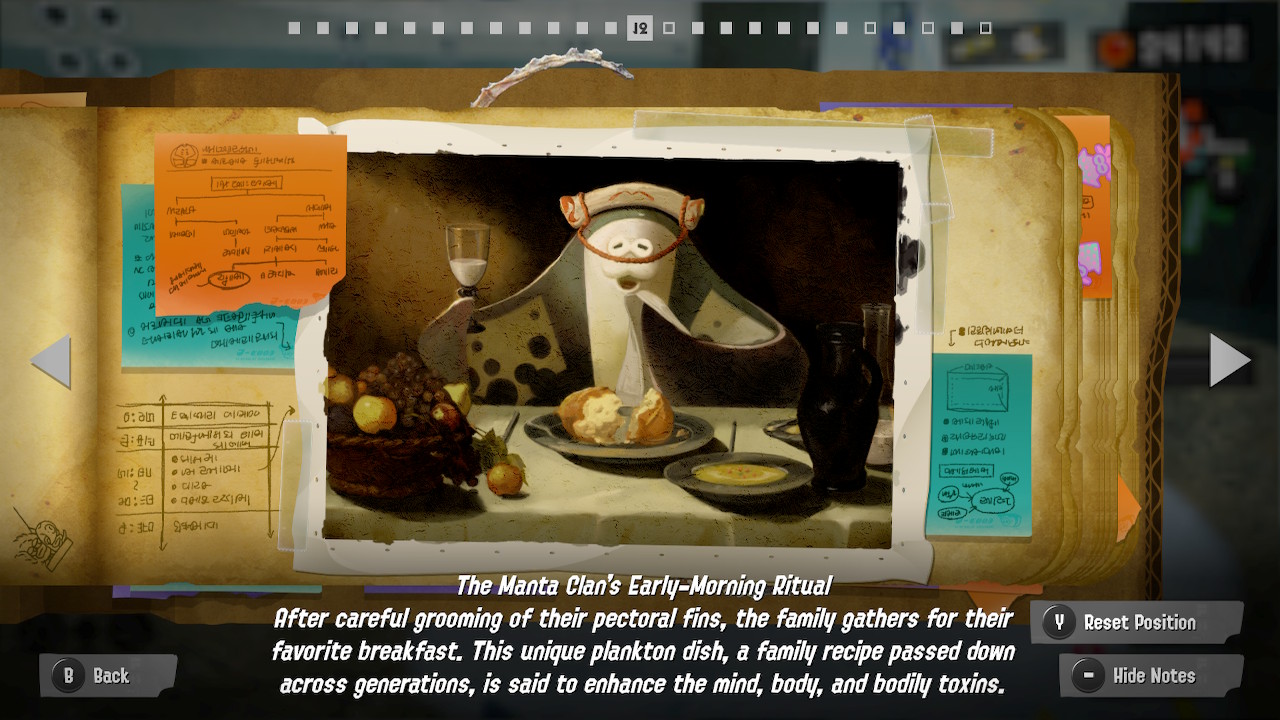

Discovery is the motif threading every disparate treasure together. As players, we search through human history to find secrets; as a game, Splatoon 3 creates its own macabre visual identity by doing the same. The morbid thrill of seeing human artefacts in an alien environment becomes the game’s greatest narrative device: eschewing the moral choices and faux-intellectualism of Bioshock, it is instead confident in the starkness of its imagery to prompt questions in the player’s mind.

As the story continues, the truth quietly blooms that Alterna was once a project designed to condense all of human culture to a single, apocalypse-safe bubble. Accompanied only by an unknown fabrication technology, the survivors delighted themselves in creating the perfect world for themselves, one with a cohesive theme and picture-perfect aesthetic. At some point, however, the humans grew restless, and sought to see the outside world for themselves. No further information is given as to their whereabouts. When we finally arrive, Alterna is desolate, abandoned; decorated with discoloured fur, its perfect pieces now lie strewn apart as both trash and treasure.

The details are fuzzy – as are the enemies, and the ground, too – but in Alterna it is not impossible to see similarities with the previous work of Splatoon 3‘s young development team, Animal Crossing: New Horizons. Here was a game defined by its saccharine utopianism, yet beneath this cutesy veneer was a gunpoint threat to design a flawless, shareable island whose very entrance would be enough to make its visitors green with envy. The beast of perfection cast its shadow over every sanitised villager conversation, every jealous online island tour, every humbling attempt at landscape design. Like the survivors of Splatoon’s apocalypse, I too found myself desperate to leave my walled garden, and now it too lies in disrepair, desolate and overrun with weeds. Wholesome is a prison. In letting us explore the aftermath of such spiritual destruction, Splatoon 3 is ultimately able to adopt a far more optimistic tone than New Horizons, and one that, despite its hurricane of influences, feels paradoxically more self-confident. It is a megaphone-wailed lesson that we will be remembered not by our lofty intentions but our tiny trinkets, mashed together and repurposed in ways we can never predict.

* * *

Young people treasure the world, too.

At a glance, the opposite feels true. We have been taught to define ourselves through media consumption, allotting all of our free time to watching or discussing the output of a single brand, and feeling personally hurt at any criticism of its creators. New releases are rewarded by a few days of discourse before they vanish into a shared black hole of memory, years of work reduced to their most controversial chunks. We must consume, and tell the world that we have done so, and – in as glib and sarcastic a manner as possible – share how we felt about it. We are at once overexposed and lonelier than ever.

It’s not enough just to be seen engaging with the “content”, either. The object of our consumption has become secondary to the ritual of consumption itself: a book cannot be enjoyed unless sipped with wine in a bath or bay window, nor an album unless cried to on a nighttime train ride. Both must be logged on their respective listing sites. This is not to disparage or distance myself from those activities – I love baths and bay windows and trains, as do all of my friends – but the idea that there is one aesthetically correct way to enjoy art speaks to a level of profound insecurity afflicting much of our generation. We must consume perfect media in a perfect manner, so that one day we ourselves might be viewed as such. Slowly, however, resistance to this idea has begun to gather.

Scroll deep enough on Instagram or TikTok and you’ll find a world overflowing with beautiful, hideous works, each built from the misshapen scraps of human culture. There are silent comedies set to SpongeBob music; Counter-Strike montages interwoven with cat videos; dreamlike skits with sweat-drenched close-ups. Family Guy clips bleed into psychological horror. Yet most captivating of this new surrealist movement are the mysterious works of cult filmmaker “Undertime Slopper”.

The encounter with the giant footprint in Albert’s Forest is just one of the account’s tales: we meet a greedy squirrel with human ears, a frog therapist whose only remedy is “chill pills,” a clay-faced artist obsessed with his self-portrait. The tone and emotions of this anthology are familiar – fragments of In the Night Garden, My Neighbour Totoro and Attack of the Friday Monsters lie in every video – yet their rearrangement here feels wondrous and fresh. A self-proclaimed “rhetorician magician,” Undertime Slopper challenges viewers to watch “every video [it has] ever made,” yet doing so does not yield some bankable understanding of its lore, the “I get it” moment to which we all feel entitled. The satisfaction of having properly consumed the work remains tantalisingly out of reach; rejected, we can neither smugly inform others of the “true message” of the work nor fully move on from it. None of it makes sense, nor does it have to. To point out that the videos have plot holes would be to say nothing at all. CinemaSins would be furious.

When viewed through the eyes of a child, our world loses its exhausted cynicism. No longer can art hide behind its shielded layers of prestige and commercialism; rather, our heritage becomes malleable, joyous, playful. As though postmodern archeologists – wankers, in truth – we root through videos whose crusted texture betrays their heritage. We watch screen recordings of screen recordings of sped-up versions of drum and bass edits of pets dancing, videos made almost more for the satisfaction of sharing a new song than for any comedic purpose. We rarely see the contents of the Inklings’ phones, yet, looking at those of our own, differences in online cultures can scarcely be imagined.

Just as Splatoon 3’s jerry-rigged aesthetic feels like a protest of New Horizons’ eerie perfection, so too have young people continued to fight against the uniformity of “content” through absurdist imperfection. For every toxic diet plan, smug day routine or Sisyphian ‘grindset’ quote, we counter with a new look into Undertime Slopper’s world, or a goofy breakbeat track, or a quote about tummy aches. Can this be art? That sounds like a question for the most annoying people you will ever meet. What is this art trying to say? That feels more meaningful.

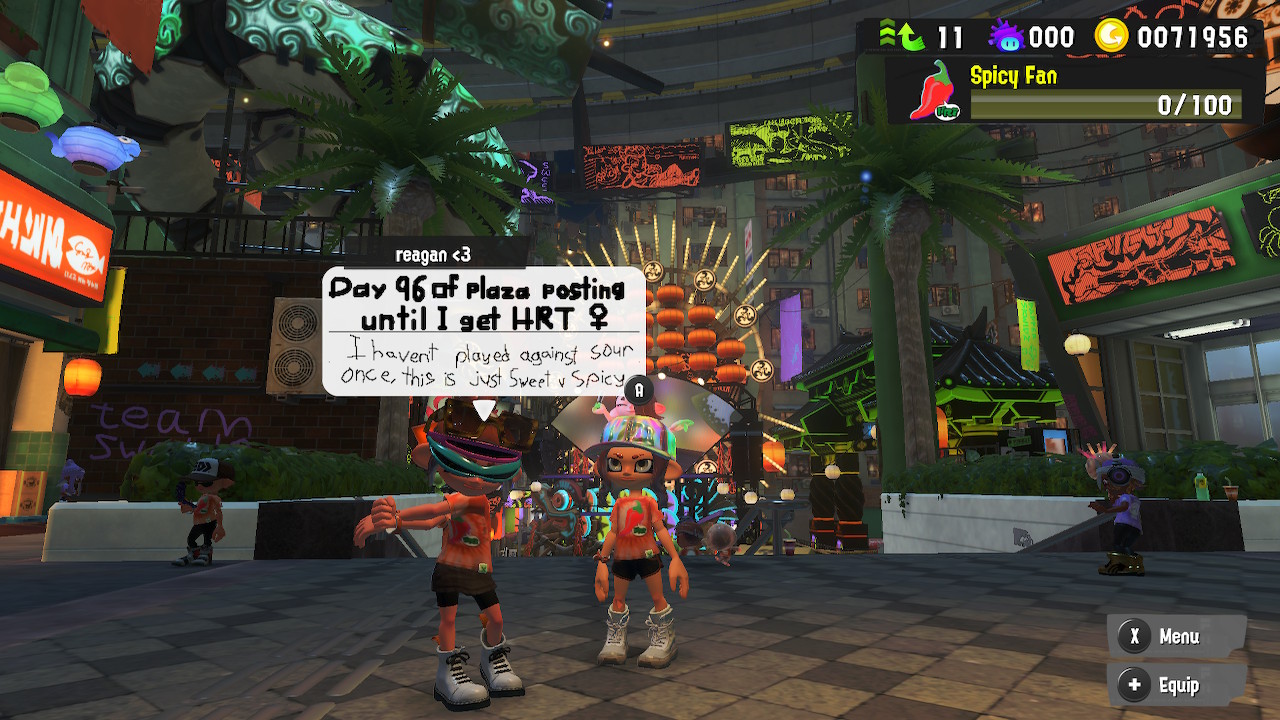

Splatoon 3 shows us not one vision of humanity but a million, a cultural Katamari whose every tattered knick-knack tells us a little more about the worldview of its creators. Defeated, we may believe that nothing created within the systems of social networks and sequels will ever have true meaning – that to live vicariously through media is the fate of our generation – yet this is an idea that Splatoon’s developers and Generation Z fight at every turn. Our creations are often strange and awkward, yet in their strangeness and awkwardness lives a wild conviction that those in power can never suppress. We can even see this in the game itself via the in-universe message board: despite its inherently competitive nature, the lack of pressure to create something “proper” renders the game more open to expression, allowing scribbled declarations of gay pride to thrive alongside wildly detailed works of (also gay) fanart.

It would be easy to condemn modern culture as a distant apocalypse, pining instead after some undefined period of prosperity, yet as taught by Splatoon 3 – and Jet Set Radio and Umurangi Generation before it – we can still be radical in our own time. The most rebellious thing to do is not to give in to selfish nihilism; rather, it is to take the means and situations dealt to us and to create something ugly, something expressive, something that takes one part of the self and offers it to those around us. Our world is an endless mass of fossilised memories spanning every emotion we have ever known, and every emotion we will ever know. With playful absurdity, Splatoon 3 skates across this unfathomable lake.

If you like what we do here at Uppercut, consider supporting us on Patreon. Supporters at the $5+ tiers get access to written content early.

Did… Did you you just make an Undertime Slopper reference?