Screenshot provided by Grace Benfell

Sports and Politics: How Final Fantasy X Resonates With the 9/11 Attacks and their Fallout

A baseball is a ball. Bullets used to be balls. A head is a ball, too—roughly. Flatten one (a ball) and you get a disc, like the things we used to put into our PlayStations. 20 years ago, Final Fantasy X came out on a disc. It was the first Final Fantasy game on the PlayStation 2 and the first to have voice acting.

Balls are important in FFX. The first thing you see in the game, underneath the setting sun and before the ruins of a city, is a ball resting against a sword and a staff that have been stabbed into the ground. This ball is one of your party member’s weapons. That character, Wakka, chucks it at enemies. But it’s also specifically a blitzball, the primary piece of equipment for the world of FFX’s favorite sport. Wakka uses the ball as a tool to both entertain and defend his homeland. Depending on how you look at it, a blitzball could be a piece of sporting equipment or a weapon or both at the same time.

Twenty years ago, when I first played FFX, I did not realize the obvious metaphor. What I thought about most was the surface-level stuff: the journey that the player character, Tidus, goes on. After the initial opening scene—a proleptic moment we don’t return to until near the end of the game—we see Tidus in the same city before it was destroyed, when it was a sprawling fantastical metropolis, when it was his home. It’s nighttime, but hardly dark under all the city lights. Tidus is the star athlete of the city’s blitzball team and is on his way to a game. After a scene of the most extreme version of water polo you’ve ever seen, the city is attacked and destroyed by a gargantuan flying whale. Later, we learn that this monster is called Sin (subtle) and that in addition to bringing catastrophe, Sin has more supernatural abilities—abilities that seemingly transport Tidus a thousand years into the future, into a land called Spira and a time where Sin is not new, but a never ending threat. Suddenly a fish out of water, Tidus gets wrapped up in a pilgrimage to fight Sin despite not knowing how to process the destruction of his home.

Twenty years ago, two months before FFX was released in North America, I started my morning like usual. I was a Long Island tween in the suburbs of New York City and was late for school, watching cartoons when the signal turned fuzzy. I flipped to another channel to see if the problem was with Nickelodeon. I happened to flip to CNN and saw one of the Twin Towers was on fire. The news anchor said that a plane had just crashed into the building. A monster of black smoke poured from a hole that spanned more stories than I could count.

When I got to school not long after, the classroom television was on and showing the same image of a burning skyscraper standing in front of its twin. Then a plane slid into view and struck the other tower. The television didn’t have sound so we just watched as the top of the building silently burst into flame. The principal made an announcement for teachers to please turn off their classroom televisions. Our teacher was crying. She turned the television off. Not long after, calls started coming into the classroom as parents came to pick up their children. We didn’t see the towers collapse but some kids shared the news at lunch. One kid said how before our teacher turned off the television, we saw the second plane hit. “It was awesome,” he said, his eyes wide with incomprehension at both the magnitude of destruction and the fact that so many kids in our school had parents who worked in the World Trade Center.

The next day, the principal made an announcement asking for a moment of silence for all that was lost and especially for the students in our school whose parents were hurt or missing or dead. This same kid who described the scene we saw on the television as awesome folded his hands and bowed his head. His name was John Paul. He was named after the Pope. He was praying.

I recall the night of September 11th, the air smelled like catastrophe. I recall being angry and terrified in equal measure. Like Tidus in FFX, I was a confused idiot with frosted tips. Like him, I lost the city I thought was mine. At the time, I didn’t realize that the game wasn’t really about Tidus. He is the player character and serves as the entry point into this world wrecked by Sin, but he doesn’t grow the way some of the other characters do. I saw myself in Tidus, but in the decades since first playing, I see the game has more to offer than a simple hero’s journey.

FFX shows a world constantly under duress. In the face of the fear and destruction that Sin brings are two major institutions embraced by the people of Spira: religion and sports. None of this is subtle. Spira is blatantly a theocracy, with the church serving as both the governing body and the framework for organizing pilgrimages to combat Sin. Sin can never be completely defeated, but people still sacrifice themselves to make the flying whale go away for a little while. The only other major source of reprieve is blitzball. As Wakka says to Tidus early on, “This is the only time! The players fight with all their strength. The fans cheer for their favorite team. They forget pain, suffering… Only the game matters!”

Wakka’s sentiment that sports and entertainment ought to function as an escape from reality is one found frequently in our world, too. Throw a stone through the internet and you’ll easily find people shouting their disapproval of “politics” in television shows, movies, video games, and other media they presumably believe ought to be limited to catering to their personal enjoyment and distraction from the world around them. When “politics” do become overt in entertainment media, like when star quarterback Colin Kaepernick suddenly stopped just playing football and started peacefully protesting systemic racism by kneeling during the National Anthem at his games, a vocal contingent of people got up in arms. They protested his protest. Then the NFL weighed in by banning kneeling. The thinly veiled racism of this response was explained by the NFL as support of patriotism, and that’s certainly a part of it, but many of those disgruntled by the attention Kaepernick received were filling their diapers for just that reason: because they were being forced to pay attention to a man’s Blackness and what he was expressing when they wanted to exclusively be watching a football game. They didn’t want “politics” in their sports, interfering with their entertainment. Just this year, football Hall of Famer Brett Favre said exactly the same thing.

Beyond the socioeconomic ramifications that sports clearly have as an industry, it’s pretty obvious that patriotism in sports is politics in sports. I first noticed the propagation of patriotism in sports in the years after 9/11. I was a little less of an idiot and went to baseball games once again. At Yankee Stadium, they played “God Bless America” during the seventh-inning stretch. They did so for every game after September 11th, 2001. They did so throughout the “War on Terror,” and just like that ongoing military campaign, Yankee Stadium does so still. This decision reifies the idea that America’s pastime isn’t just about passing the time—it’s about unity in one way or another.

Unity is important. We cannot survive on our own. We need communities to protect each other from cold and hunger. We need unions to protect each other from those with the power to exploit. But when groups become about supporting ideas instead of people, and when those ideas support the hegemony of the state, you get what the philosopher Louis Althusser coined as Ideological State Apparatuses—ISAs being the institutions that don’t explicitly and violently repress, but still serve to indoctrinate people with the dominant values of society.

In the United States, sports and the church are legally recognized entities that, while diverse and fluid to an extent, have always supported the power structures they fit into. When you hear “God Bless America” playing over the diamond at Yankee Stadium, and see all the digital banners that usually show ads turn to images of the American flag as the jumbotron zooms in on a military veteran or their family, it isn’t just about paying respect or feeling like everyone there is unified; it’s about the value of God, patriotism, and the military in American culture. It’s also about propagating ignorance of what falls outside of that paradigm. Those are the values that an ISA supports, not a man kneeling to draw attention to those killed for the color of their skin.

After 9/11, playing FFX offered me catharsis by showing me how Tidus went on living after witnessing the destruction of his home, but now I see what the game has to say about larger apparatuses like sports and religion. Quite a lot, it turns out. Throughout the story, you see how blitzball is not just a distraction from the pain that Sin brings; it is a distraction from what the church is really doing: keeping people in the dark so that those in power stay in power.

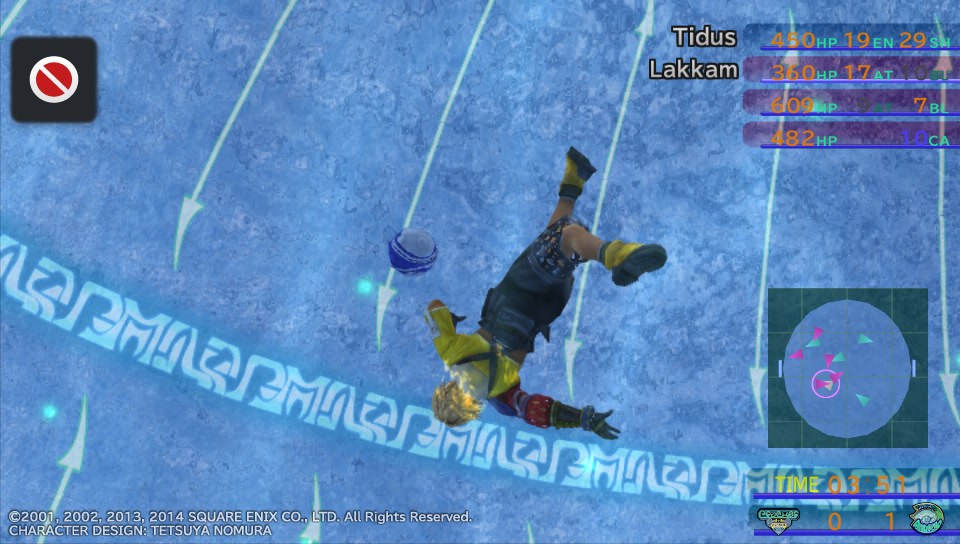

This would all be cut and dry in a less nuanced narrative—sports and the church are the opiate of masses, et cetera. But the story FFX tells is more mature than that. We see the treachery that the church commits, but we also see how people’s faith allows them to have hope in the face of inevitable doom. We see blitzball as both a distraction and tool for further societal division, but we also see how it brings people together with joy and purpose, even if that purpose is manufactured. We, as players, can also play blitzball instead of furthering the story.

The Final Fantasy series has often had minigames, but few have been as elaborate as blitzball. You can play out an entire season, which works like a turn-based, underwater, rudimentary version of FIFA. It’s full of flashy lights, dramatic music, and it is extremely boring. It is also extremely odd in the way it is implemented in the game. After a certain point, you can start up a blitzball game from any save point you find in the overworld. You could be on the Thunder Plains dodging lightning and take a break to get a few matches in or scout some new players. You can quite literally distract yourself with blitzball in lieu of the rather urgent story to stop Sin, stop the church, save your friends, et cetera. Herein lies the real genius of what FFX has to say about sports, specifically, and games in general: you have to decide what matters; you might not be able to change the story, but to a degree, it’s up to you what you give your attention to.

You can play blitzball for the rest of time and put off beating the game and seeing out the plot. If you do, you’ll have to face the dissonance of being in the middle of an emergency and ducking out to play ball, but it’s still up to you. At the very beginning of the game, as the sun goes down over a ruined city, the first words spoken are, “Listen to my story.” But listening does not just mean sitting there and letting information wash over you.

After 9/11, I constantly watched the news. I was angry and scared about what could happen to me and the place I lived. I felt like something had been taken from me. But then the footage of firefighters and recovery efforts turned to broadcasts of the United States invading Afghanistan. Like anyone paying attention, I’ve seen how the United States’ response has taken away from the rest of the world as well. The “War on Terror” continues on, parts of the Middle East continue to be unstable, and there are people being left behind. Those are who I want to listen to now. I cannot look at images of the Twin Towers falling without weeping, but I am not distracted by my own terror—despite often being as terrified as I am embarrassed for God’s sake and my own—the way I once was. Instead, I try to pay attention.

You can have fun and think at the same time, after all. Maybe you find blitzball fun. Let me know if you do! As for me, I never did—and to be honest, I don’t find much of FFX fun anymore. It reminds me too much of September 11th, 2001, and everything that followed for me to have a ball while playing. But I find it meaningful. When the game asks me to listen, I do. There is a reason you have to press X to move the story forward. You have to choose to listen, and when you do so, it is your responsibility to think about what you hear and why you’re hearing it—whether that’s at a ballpark, in a church, over a news broadcast, or even in a video game.

This was very good and I liked it. Thank you for writing it.