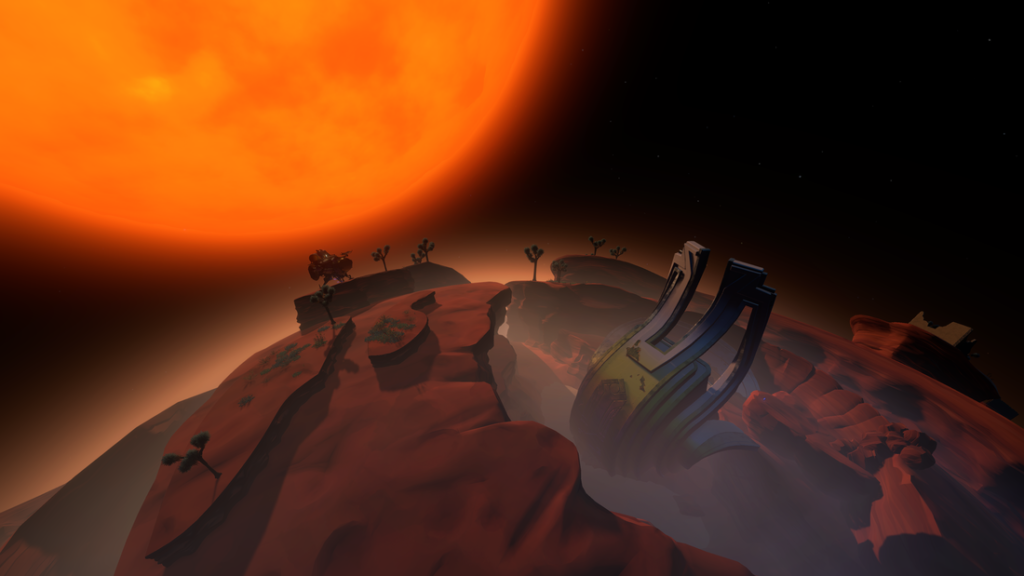

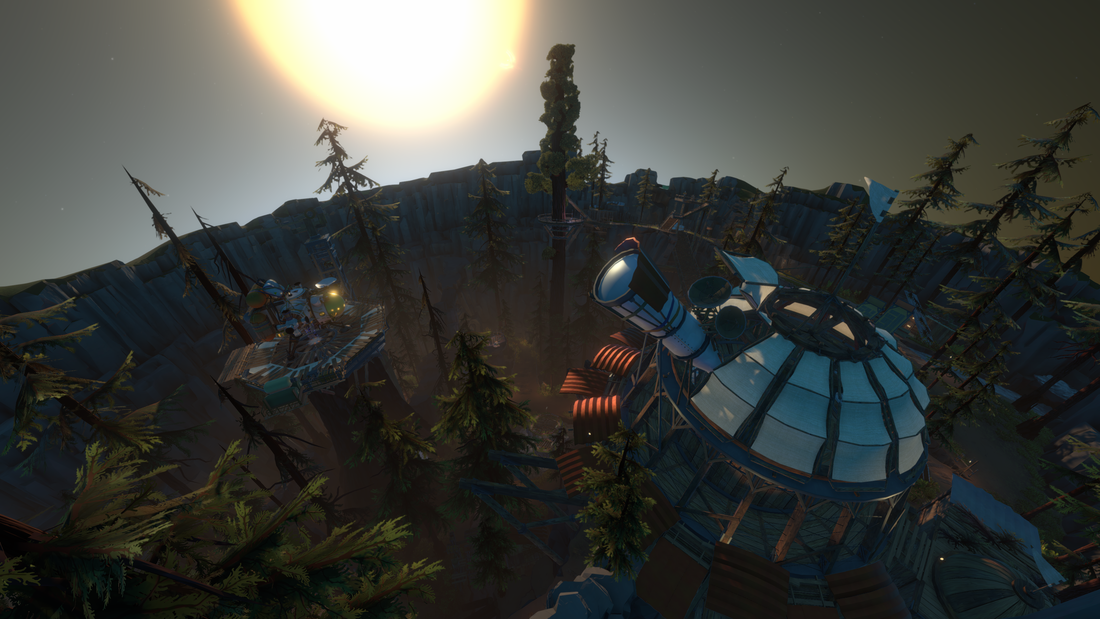

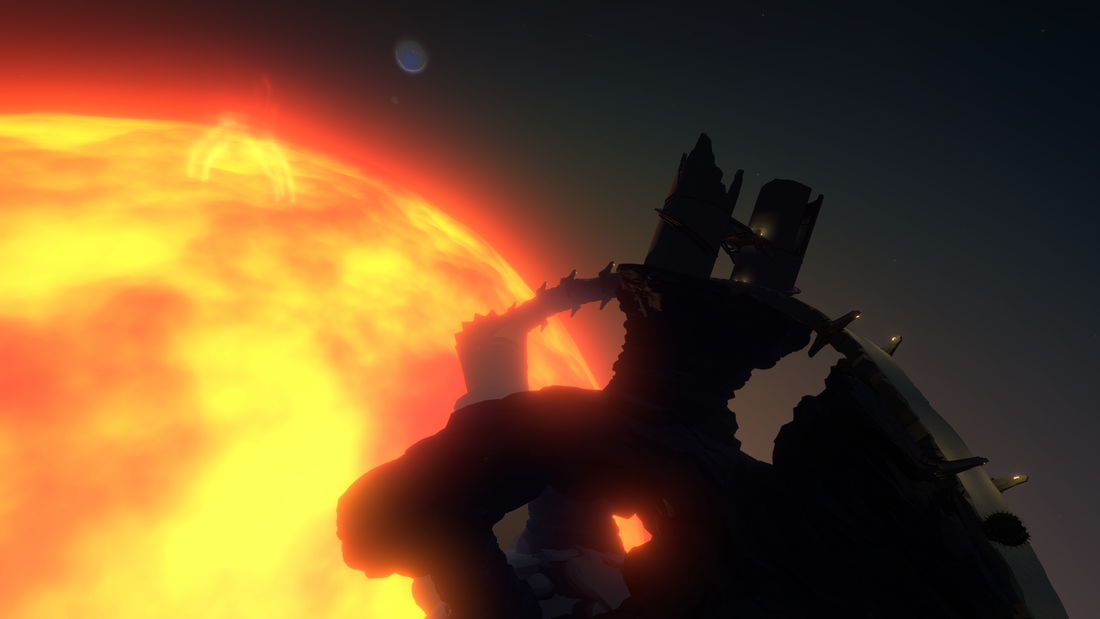

Provided by Mobius Digital

Station Eleven & Outer Wilds: Emotional Magic at the End of the World

Warning: this article will feature spoilers for both Outer Wilds and Station Eleven.

No matter what you watch, read, listen to, or play, there is a certain, indescribable feeling that art can conjure up inside of us. A rush of emotions, like a deep nostalgia for places you’ve never been or people you’ve never met. It strikes at the heart of what art is and why it’s important to us. I felt it playing Outer Wilds, a small indie game that began as a class project, and I felt it again recently watching the post-apocalyptic Station Eleven, based on a book of the same name. These two works are similar in as many ways as they are different, and they both ignited this intense emotion within me. Frustratingly, I never had a word to describe what that emotion was. Until now.

One cold, rainy night I was curled up at my desk watching the latest (seventh) episode of HBO Max’s Station Eleven. On my screen stood this child, Kirsten, and her unlikely companion, Jeevan. They were sullenly preparing to leave their shelter. The two had been staying with Frank, Jeevan’s brother, in his lofty, downtown apartment. It had, until then, served as their home and refuge from an apocalypse in the form of a deadly flu that killed 98% of all human life over the course of days.

Kirsten and Jeevan had just suffered a deep loss at the hands of an intruder. Frank was killed by the intruder. Now they had to leave. As they prepared their belongings and started off on this new journey, the music began to swell. Strings shivered behind the banjo. It builds and builds until all at once many instruments burst forth; a horn, strings, perhaps an accordion, too. They all come together, singing the series’ signature melody. It’s this big, swaying, hopeful tune; Dan Romer’s Doctor Eleven. I became flooded with emotion. I felt a connection to these characters, felt what they must’ve been feeling. The scene and the music dragged me from my chair into that world. I didn’t know the word for that emotion at the time.

What I did know was that I recognized that feeling. I’d felt it before, more than once. Every song that I cherish, the movies that I find myself watching again, year after year. The books that never seem to make it back to my shelf. The one thing they all have in common is this ability to evoke some sort of emotional chain reaction within me. Maybe you’ve felt it, too.

Duende is an emotion, an expression, often described in tandem with Flamenco, a Spanish artform. A combination of music and dance, Flamenco isn’t just a genre but a genuine expression of emotion – the duende is a feeling felt not only in reaction to Flamenco, but in reaction to many forms of art. It is often associated with themes of life, death, and struggle. I could attempt to describe it further, but Federico García Lorca does a better job. The following excerpts come from Language Magazine:

“Everything that has black sounds in it has duende [i.e., emotional ‘darkness’] […] This ‘mysterious power which everyone senses and no philosopher explains’ is, in sum, the spirit of the earth, the same duende that scorched the heart of Nietzsche, who searched in vain for its external forms on the Rialto Bridge and in the music of Bizet, without knowing that the duende he was pursuing had leaped straight from the Greek mysteries to the dancers of Cádiz or the beheaded, Dionysian scream of Silverio’s siguiriya.” […]

“The duende’s arrival always means a radical change in forms. It brings to old planes unknown feelings of freshness, with the quality of something newly created, like a miracle, and it produces an almost religious enthusiasm.” […]

There it is, duende. The word I’d been searching for. I asked myself where else I had felt it, and how intentional it was on the part of the creators that the audience experienced it. Days later, driving to work, a familiar song played from my Spotify playlist. Outer Wilds by Andrew Prahlow. Even though they don’t use the word duende, you can see the feelings that went into it when you hear Andrew talk about composing for the game:

“Even back in the alpha and beta stages, [Beachum and I] always loved the idea of having them alone playing on separate planets, but really playing as a band all together … It creates a really cool concept of how we as humans can be emotionally connected no matter the distance. I love thinking about our purpose on this planet – that we live on in this massive expanding universe, and through music, it gives us all an opportunity to connect and make it feel a little more like home.”

It’s no coincidence that myself and others experienced duende with both Outer Wilds and Station Eleven. Both share many similarities.

Outer Wilds is a video game released in 2019 in which you play a nameless alien wandering their solar system (the Hearthian race, to which the player belongs, have no gender), searching for clues about an advanced race of aliens, the Nomai. They explored those same worlds eons ago. Their structures and skeletons are littered about the solar system, as though they all died at once where they stood.

Both Station Eleven and Outer Wilds deal in similar themes: acceptance. They’re about finding silver linings to otherwise dark clouds. In Outer Wilds, your first playthrough is innocent and aimless. It’s only after 22 minutes that you realize the sun is about to go supernova and destroy… everything. And it does; but that’s not the end of your story, not yet. The player finds themselves waking up beside the campfire, the same way the game started. You’re caught in a cosmic version of Groundhog Day, only you aren’t Bill Murray. You come to realize that nothing you do in this game can prevent the end of all things; all you can do is accept it, and try unraveling the mystery you started with.

Station Eleven isn’t as grand in its scope, but the feelings are all there. Kirsten loses everyone, and never gets to say goodbye. Her parents died and she wasn’t there, her mentor Arthur Leander died before she got to go on stage, Frank died while she hid from an intruder, and her best friend, her guardian angel, Jeevan, vanished in the night. Kirsten survived the apocalypse but continued to experience loss without a modicum of closure. Yet, when the sun comes up, it rises on a world rid of humanity. A world without eight billion people is one full of nature and renewed wilderness. In it, those left must find happiness in the blank slate that is now their world. The author of the original novel, Emily St. John Mandel, touches on this in an interview with the New York Times:

“What they really did beautifully was capture the joy in the book. It is a post-apocalyptic world, but something that I thought about a lot when I was writing the book was how beautiful that world would be. I was just imagining trees and grass, and flowers overtaking our structures. I thought of the beauty of that world, but also the joy. This is a group of people who travel together because they love playing music together and doing Shakespeare, and there is real joy in that.”

Kirsten retreats from the real world into the titular comic book given to her by Arthur, Station Eleven. The comic was written by Arthur’s ex-wife, Miranda Carroll, who was also struggling with her own personal apocalypse, her own total loss. She confronted and expressed that loss by writing and illustrating Station Eleven, the in-universe comic. Though she and Arthur are long dead for much of the show, the ripples of their lives interact with Kirsten’s future, and of those around her. In a way, Arthur and Miranda, in death, put Kirsten and others on a path to reconnecting, to letting go of the past and making new memories in the new world. They need to let go of life before the flu. Accept the clean slate. As Tyler, the closest thing the show has to an antagonist, says: “There is a before; it was just awful.”

At the end, both stories are about learning to say goodbye. Learning to accept the end of the universe or accepting the end of your time with another person. To carry that lesson all the way through, in order to incept that idea into your soul, they use duende as a tool. It isn’t enough to see these stories; you need to feel them, too.

Station Eleven gives us these rich characters who are bound together through Arthur Leander in a beautiful, post-human world. They show us that one can make a family out of whoever they end up with. They show us how to say goodbye. All of this in tandem with music to get the duende flowing.

Outer Wilds uses an inexplicable time loop that traps you with this ancient mystery of an apocalypse that already happened. Add to that the spirit of exploration and discovery combined with Prahlow’s music, we feel the same emotion. All of these elements are shone through a lens, focused to a laser-point, to allow you, the viewer or player, to feel the work and not just watch it or play it.

That’s the magic of duende.

That’s the gift I’m hoping you’ll enjoy. A name to describe the thing you felt watching Roy Batty give his monologue about memories in Bladerunner. It’s that rush you feel when the right song just takes you. Duende is a religious experience wherein the art itself is God. To me, duende is why we make art. It’s the best way to capture the human experience, and share it with others. It’s not an easy thing to achieve, and in my opinion any work of art that can spark duende within you is worthy of praise. In that regard, Station Eleven and Outer Wilds have succeeded.

If you like what we do here at Uppercut, consider supporting us on Patreon. Supporters at the $5+ tiers get access to written content early.