Video Game Beards as Visual Storytelling: A Transgender Perspective

Mustaches as metaphors, soul patches as symbolism and facial hair as a framing device

The average man shaves 20,000 times across his lifetime. Just like brushing your teeth or washing your face, it’s part of the daily personal maintenance of being a human. With the recent global lockdowns, shaving might fall by the wayside for some of you, and once Covid-19 passes by, you’ll emerge from your self isolation sporting Tom Hanks Castaway beards- a whimsical scenario for many of you to imagine. For me, it would be my worst nightmare.

Shaving was, for a considerable time, the best and worst part of my day, and I know there are other women out there like me. Shaving was not just the act of trimming excess hair off my face, but both an act of submission to my gender and rebellion against it. Shaving removes the outer signs of your masculinity, but forces you to look in the mirror and become acutely aware of it.

For trans women like me, shaving was like grinning up at the bully while you’re on the floor, blood pouring from your nose as you stagger to feet, taunting them to give you more. It kind of feels like a moral victory, but it’s really a crushing defeat. Facial hair was the thing I’ve always loathed the most about my pre-transition body, much more so than that fabled “down there,” beards are constantly on show. Everyone can see them. Everyone knows what you are.

Unsurprisingly, we don’t always like smirking at the bully while they pummel us. From whenever my peach fuzz came in until I was around 22, I gave into it. Our community has what’s called a “denial beard,” (when trans women still closeted, perhaps even to themselves, grow out their beard) with Reddit subs, discord chats and message boards awash with mighty specimens sported by women now unrecognizable. While I never reached those levels, I did wear a rough looking stubble wherever I went.

In the years since, I’ve undergone hormone-aided transition and had practically every trace of my former facial hair methodically removed with lasers. While my beard has been burned away, my connection with it has not. In seeing what it takes to get rid of it, I feel like my appreciation for facial hair has increased. Like a knight having slain a dragon, I no longer see the fuzz as my enemy, and instead as a misunderstood beast on the wrong side of my personal history.

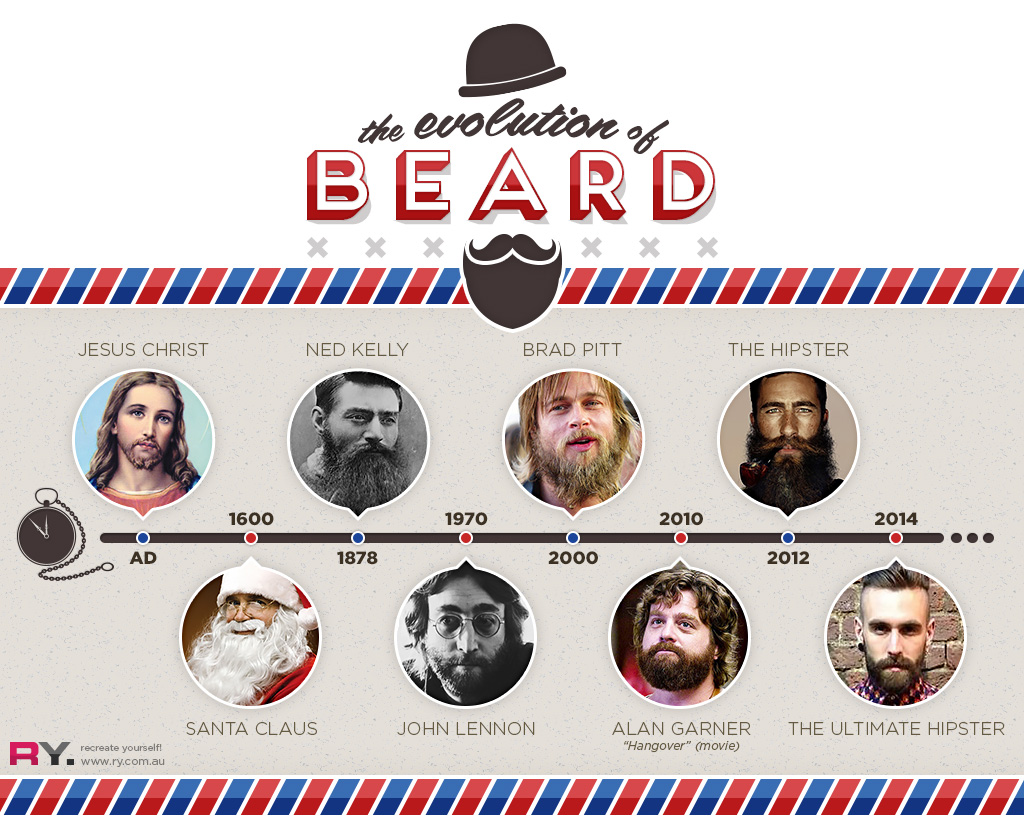

Facial hair has always been a part of culture. If you ever step into a time machine—first off, don’t touch anything—you can probably tell what era you’re in by paying close attention to the ‘staches. The 21st Century rise of the hipster beard has brought facial hair back to cultural prominence, replaced recently by the fade. Despite (or, perhaps more accurately, because of) my complex relationship with facial follicles, I find these cultural indicators fascinating.

Video game facial hair has its own evolving history, though it started less as a cultural signifier and more as a technical requirement. Arguably the most famous facial hair in all of video games—Mario’s mustache—was created because of limitations of 8-bit visual design. In the first design of Mario, Nintendo’s developers found it difficult to create an 8-bit mouth that didn’t look like a mustache, so they just leaned into it. The hat too, exists because it was easier to give a distinct shape to than the outline of hair. His name, for what it’s worth, comes from Mario Segale, the angry landlord for Nintendo of America’s warehouse. These days, the development of triple-A games is a well-oiled machine with hundreds if not thousands of people toiling tirelessly on every little detail. In the early days of the all-time greats, though, there was a lot more “flying by the seat of their pants” going on. Mario’s mustache remains the pinnacle of video game facial hair, but it’s only there because it was the simplest thing to implement. As technology advanced, facial hair moved from being a programming short cut into a fully fledged storytelling device.

In more ways than one, Mario is an outlier of early video game fuzzy faces. Mario’s mustache offers a design flourish and a programming shortcut, a lot of the deliberate facial hair in early games involved a long white beard. A simple to implement, easy to recognise design, the mystical wizard beard found in adventure RPGs like The Legend Of Zelda might have been the first use of beards as visual narrative in video games, but it certainly wasn’t the last.

While long beards signified wisdom, shorter ones pointed towards evil. Much like the black and white hats of the Wild West, beards were an early indicator of morality. Good guys were mostly clean shaven, while several villains repped soup strainers. Without voice acting and with narrative limited by technology, villains had to be elevated to caricatures to fully sell their villainy. In 1987, Doctor Wily made his Mega Man debut, while four years later Doctor Robotnik (Eggman, if you’re nasty) first hit screens in Sonic the Hedgehog. Both instantly looked the part of baddies, clearly modeled off mad scientists. Moving further into the 1990s and into the fifth generation of consoles with the PS1, the likes of Neo Cortex (who grew his moustache out into a devilish goatee) and Heihachi Mishima followed suit when they first appeared in Crash Bandicoot and Tekken respectively.

The ‘90s was possibly the most cartoonish decade for gaming. It brought us Duke Nukem (clean shaven, naturally, as a hero), Twisted Metal and PaRappa The Rapper, the era when John Romero was going to make us his bitch. The mad scientist trope is just one example of how over the top character designs were as the 20th Century was ending, but together they paint a picture of mustaches as a signifier of evil. In the real world, the facial decor of choice for the ‘90s was the alt goatee or chinstrap, the kind of whiskers you’d have spotted on the likes of Fred Durst and Kid Rock. Whether you were trying to take over the world in a video game or simply repurposing the punk rock movement for your own unclear political nihilism while producing subpar music, forgoing the razor in the ‘90s meant you were a little out of step with the rest of society. As men of the world embraced the permanent five o’clock shadow into the 2000s however, video games had to pivot too.

The first sex symbols of the 21st Century were the likes of Hugh Jackman and Russell Crowe. Ruggedness replaced the bubblegum appeal of Justin Timberlake, and with that came the rise of the bearded video game hero. Graphics improved to the point where people in games actually looked like people, and so character designs could be used to tell far more sophisticated stories. Unfortunately, if often felt like they were telling the exact same story, over and over again. The Last Of Us and BioShock: Infinite feature completely different narratives with vastly different themes, but Joel and Booker have incredibly similar designs. Both are white men, stocky and ragged, and while Joel’s beard is fuller than Booker’s rough stubble, both are clear signifiers of their masculinity.

Both of them are defined by their masculinity and ability to survive on their own, keep others at a distance, and both are responsible for a daughter figure and display their tender humanity through caring for her by proxy. The Last Of Us is a lighthouse away from being an offshoot reality in the BioShock universe set during a deadly outbreak.

It’s easy to just dismiss their beards as part of the ‘every game protagonist is a generic white guy’ trope, but it’s clear they represent something deeper. Their beards are an embrace of rugged masculinity, a clear signifier of their defining trait in the ways I had always most feared. In their own way, Joel and Booker are wearing denial beards. Their thick stubble is a denial of any vulnerability. It marks them out as an everyman, yet at the same time separates them from the herd, identifying them – and them alone – as the one best equipped for adversity, the only one who can get us out of this mess, whether that means killing zombies or dethroning a corrupt dictatorship.

There are, of course, some examples of modern visual storytelling through beards which don’t rely on the go-to Jon-Hamm-between-projects look. Dragon Age: Inquisition, has a much more fanciful take on using facial hair to define characters, with companion Dorian coming equipped with the twirliest of lip hair.

Dorian is from Tevinter, a land mentioned throughout Dragon Age but never visited and rarely represented by the game’s core characters. While almost every other companion across the trilogy hails from Thedas, Dorian is a stranger from a strange land. His glorious mustache certainly has an air of the mysterious foreigner about it, but it has more layers than that. It’s worth noting that all other companions in the Dragon Age trilogy have either standard beards or no beards at all.

Dorian is an outsider in Thedas because of his homeland, but he’s an outsider in his homeland because of his sexuality. Dorian is a gay man, and his father’s failure to accept this has damaged their relationship; something you must work to mend in order to truly gain Dorian’s trust. With this added context, Dorian’s moustache goes from a mere flourish of visual characterization to full-on rebellion.

Whether or not gay men have reached equality with their straight counterparts is a debate for another day, but undeniably if equality has been reached, it has only been reached recently. In the 1970s & 1980s, gay subculture was beginning to pierce the surface of society in a delightful and angry clash of masculinity and femininity. Queen’s “I’ve Got To Break Free” video is perhaps the most mainstream example of this, with Freddie Mercury dressed as a housewife vacuuming while proudly displaying his distinctive moustache. The biker from The Village People too had an iconic moustache, one which declared loudly masculinity while unashamedly embracing homosexuality. The gay community used moustaches to label themselves as men, to push forth their masculinity – their masculinity, not what society demanded masculinity be – proudly. Through his dainty moustache, coiffed hair and lyrical speech patterns, Dorian too mixes what we would now label metrosexuality to be a man entirely of his own definition.

At the opposite end of the spectrum from Dorian’s lightly trimmed, elegant mustache is God Of War’s Kratos and his lumberjackian, overgrown beard. In 2018’s soft reboot of the franchise, Kratos has the bedraggled beard of a hunter and of a new father. Burdened for the first time by Atreus, Kratos’ look (and indeed his general nature) is not unlike the generic protagonist look of Joel and Booker, just flipped into overdrive. As veterans of the franchise will know however, things weren’t always this way. When Kratos first appeared in 2005’s original God Of War, he had a shorter, more youthful beard, and a character to match. Angrier, more reckless, driven by vengeance rather than responsibility or duty, 2005’s Kratos was very different to 2018’s. Both will kill you with a single slash of their axe, but 2005 Kratos will relish the prospect, while 2018 Kratos will rue your stupidity at ever crossing his path. 2010’s God Of War III continued in the same vein as 2005, but the beard was a more style conscious soul patch, and the man behind the Blades of Chaos was cockier with his swagger, more inventive with his killing. With Kratos, the beard is a window to the soul.

The most recent major development in the world of video game beards has been beard growth mechanics. First introduced in The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt, another well known version of this mechanic can be found in Red Dead Redemption 2. Of these, it’s Arthur Morgan in Red Dead who captures the potential of this mechanic best. The Witcher’s Geralt is on a rather fixed journey, with an established personality, and his beard matches; it simply gets longer with limited options to personalise it. Arthur, however, is whatever you make of him. There’s a thousand different ways to play Arthur Morgan’s personality, and with Red Dead’s beard growth, there’s a thousand different ways to style him too.

The introduction of beard growth has done a few things. For one, it’s a reminder to people like myself that most people don’t view shaving as a torturous battle against the self, but as a regular chore of life, perhaps even one they enjoy. It also offers you an additional agency over your character and their place in the world. Is your Arthur Morgan a dapper dan? Pomade his hair and give him a neat wet shave, and he suddenly looks the part. See him more as a man of the wilderness? Let that bushy beard grow and grow until he looks like a mountain man. Rugged stubble, stylish goatee, hipster fresh… whatever kind of Arthur you’re playing as, there’s a beard for that. Characters have long been defined by their beards. Thanks to the beard growth mechanic, you can now define a beard by your character.

The characters mentioned here all have iconic facial hair, but when I think of beards in gaming, I will forever only think of one example. Persona 3 features a scene at a beach where a trans woman predator is outed as a man by a bit of stubble she’s missed on her cheek. Persona’s distaste for queer people should not be a surprise; Persona 2: Innocent Sin deliberately misgenders a trans man, Persona 4 allows you to “cis-ify” a trans friend, Persona 5 is loaded with repeated gay panic, and Catherine, made by Persona developers Atlus, has one of the worst examples of the trans trap trope in fiction. It’s the scene in Persona 3 which hits me deepest, however, by not only playing into the trans predator stereotype, but because it also strikes at the deepest fear many trans women have: that our own face will betray us, that the morning’s moral victory was all for nought.

As cultural signifiers go, beards are perhaps the most interesting because they are a part of you. Clothes or hats can be taken off and swapped with ease, but beards, while they can be styled and trimmed, cannot be interchanged so easily. Even tattoos, the other major wearable fashion statement, simply go from not existing to being permanently etched onto your body. Beards require care, patience and constant upkeep. Characters who wear them do so very deliberately, though they might reveal far more than the wearer ever intended. Beards might fascinate me, but when I look in the mirror, I never want to see one again.

1 thought on “Video Game Beards as Visual Storytelling: A Transgender Perspective”