u/AD_571 celebrates Eid in Animal Crossing after Saudi Arabia goes into lockdown.

Why Online Multiplayer Isn’t So Social

(Image credit: Mari Mobility Development Co.)

‘Metnka119 won this race’ claims Mario Kart Tour with disarming confidence. Only, there is no ‘Metnka119. Mario Kart Tour was single-player only on release and filled its races with virtual facades to mask this fact. Multiplayer can’t really get more asocial than this placeholder presentational nod, but in a way this feels like the absurd but logical endpoint of a trend towards ‘asocial social gaming.’ To introduce a useful academic term here, ‘social capital’ is understood as the ‘features of social organization such as networks, norms, and social trust that facilitate coordination and cooperation for mutual benefit.’ It could also be said to mean how influential you feel in a group. Given that Mario Kart Tour’s online multiplayer with its very surface-level social systems hardly facilitates any of this, what really is the difference between racing a real or virtual Metnka119? AI outperforming humans might define the next decades of our lives, but right now we’re already letting them be our effective equals by robbing multiplayer experiences of notable humanity. The Mario Kart franchise continues to be one of the biggest local multiplayer darlings around after nearly three decades. The simple act of being able to scan someone’s face for emotion in local multiplayer or the litigated ‘Street Kart’ leaves Mario Kart Tour in the proverbial dust.

There are hidden tensions at the heart of online multiplayer design. One of the primary goals of online multiplayer you would think is cultivating social activity and the acquisition of social capital therefrom. This is important. Social connectedness (how connected you feel to society) has been shown to be important for physical and cognitive health and well-being. As I will go into, however, across the spectrum of multiplayer experiences there seems to be a generalised shift towards this not being the case. What should be a contradiction in terms, social games in many ways seem to be getting more asocial. However, the complex interaction that this is, the relationship is two-way. What you stand to gain socially depends on your motivations, what you engage with and even your cultural values. Both sides stand to feed and rob from the other. Perhaps what we bring to online experiences is also a problem?

The state of social gaming in all its permutations might seem an odd thing to assess in such tumultuous times, but I’d argue it’s very relevant to this moment we find ourselves in. When wearing masks during a pandemic has become political, significant divergences in governmental approaches to the Coronavirus pandemic have lead to higher death counts, and global activism calls for systemic change from our racist neoliberal reality and all its consequences, it seems the slow trudge of a global trend towards individualism over collectivism has suddenly crystallised for all to see. As a massive global hub of social activity, gaming has a lot of fascinating things to say about the dynamics of these supposed diametric opposites.

Whilst ‘asociality’ can’t be said to be entirely synonymous with individualism, it’s interesting to relate the slow creep of asocial elements in online multiplayer games to this cultural dimension. Gamers the world over will have been leaning on their hobby a tincture harder in the COVID era for an array of reasons. To quell anxiety and pass the time in lockdowns, sure. As a means of virtualising social interaction in the social distancing era, certainly. Twenty-nine percent of U.S. gamers said that they have been playing more with friends online since the Covid-19 pandemic began. Outside Zoom being the technological face of the crisis, gaming sits proud as the de facto social infrastructure for many. Gaming social media has undoubtedly selected Animal Crossing as its poster child. It facilitated ‘normality’ in risibly inventive ways from allowing Muslims to celebrate Eid al-Fitr, Tinder users to go on dates, graduation ceremonies to go ahead (boasting a commencement address from congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez no less), a global pride festival to be run, a platform for a late-night talk show from the writer of Rogue One: A Star Wars Story, and a political platform for a whole range of issues.

When people have been isolated in their homes and needed it most, how ‘social’ is online multiplayer really? Has there been a generational shift in how social games are engaged with or how they’re designed as a result of this global trend towards individualistic values? If there has, then does online gaming reflect or even contribute to the sociological and ideological rise of individualism globally or even a generational rejection of it? I was keen to find out.

‘Unfortunately, we’ll have to pass on this opportunity,’ has been a common refrain I’ve heard over the past few months. ‘We’ve reached out to the team and we’d be unable to get you the relevant information for your article.’ Data on player demographics from development teams themselves might have been a long shot, but the small chance at getting a complete overview of game usage according to player age/generation to put into a cultural perspective was too good not to push for.

Epic and Blizzard aren’t just being disobliging for the sake of it, the data likely doesn’t exist, certainly in any academically significant sense. ‘All Blizzard collects is credit card information,’ as Alyssa Venn of Kennesaw State University points out. A dead end, then? Thankfully, existing academic work filled this void in my research, even if such work was forced to rely on less reliable survey slices of these virtual populations.

Even outside of the gaming realm, it’s fascinating to mine studies for the shifting understanding of our favourite social constructs, individualism and collectivism. They describe the seemingly dichotomous cultural values that summarise how someone sees the relationship between individuals and society. Individualism is usually marked by detraditionalisation and the values of ‘independence, individual goals, and self-reliance.’ Collectivism conversely emphasises the collective over the individual, and values of ‘group goals, and interdependence.’ Both have their reputations. ‘Radical individualism’ is seen as a neoliberal delusion of meritocracy when factors like class are still important in determining autonomy and expression. Collectivism is seen as being anti-progress and innovation with an over-reliance on tradition. Both are more complicated than their repuations and neither hold claim to every advantage. Most importantly, however, is that theirs isn’t a relationship of dichotomy, but a partnership. Both can synergistically create effects like ‘collectivistic independence’ that takes advantage of both sets of values to get the best out of groups. It’s a complicated topic with even the very nature of individualism being questioned by academics, but it still lends itself to interesting discussions.

“It might be worthwhile to consider the importance of producing salvage ethnographies of virtual worlds,” Alex Golub suggests in reference to World of Warcraft. An anthropological term normally reserved for committing the details of indigenous culture to paper before they’re lost forever to the ravages of modernisation, it’s oddly apt. Gaming is notoriously substitutional. New multiplayer releases are expected to entirely roll over former games and their communities. Wholly apart from any intrinsic value communities might offer, there are things we can all learn from virtual culture and behaviour. The now infinitely relevant 2005 incident of the ‘Corrupted Blood’ pandemic in World of Warcraft had such close parallels to actual pandemics that it was used to model behaviour; a foundation for research pertinent to the current pandemic. Virtual culture can not only be so close to that in the flesh that it can be used for study, but surely by implication it can also be similarly stimulating and rewarding.

(Image credit:Blizzard/Twitter/Wowhead)

I’d even go one further than Alex. You don’t have to go to massive multiplayer online role playing games (MMORPG) like World of Warcraft or Eve Online, however more attractive the direct comparisons, to see real world-esque culture spring forth. Even the fractured world of first-person shooter matchmaking carries a culture and social capital with it. Perhaps that’s the point. Modern multiplayer game design and systems of matchmaking over server browsers and part chats aren’t an absence of community, but an individualisation of it. As much as we like to think of culture as some grassroots expression of community interactions, it’s the top-down placement of the paving slabs that determines where the shoots can grow.

My favourite expression of in-game virtual culture might be the language-barrier crossing feature of emotes and gestures. The fighting game, Absolver, much like Dark Souls, often features only 1v1 PvP battles. In online games it plays a brief introductory cutscene wherein your characters bow to each other. Enter the match in earnest and what do people reliably do? Bow at the first opportunity. The forced gesture almost community-wide isn’t interpreted as sufficient. Like a social contagion, the common courtesy of consciously bowing caught on. I also understand that in Hearthstone’s culture of emote-usage, emotes are powerful enough to be considered bad manners or harassment and there is as such proper etiquette to follow. It’s fascinating that such community etiquette forms for such limited tools with such unexpected power. Far from eliminating the potential for offence or abuse they seem to just abstract it. I know that whenever I’d play Absolver or Dark Souls and didn’t receive a bow back I’d be enraged at the social faux pas.

Whilst many will be glad we’ve seen individualisations like increased secularisation around the world, the diminished role of church communities in people’s lives and the social void for which that leaves is something many different things now have to fill. What value then do online communities offer to an individual? If one thing is clear it’s that we’re natural human detectors. In fact, outside of any social gain there is still some value to be found. Playing competitively against human over AI opponents increases ‘a player’s spatial awareness, anticipation of threat, the feeling of challenge, engagement, physiological arousal, enjoyment, and emotional response.’ This is simply amped up even further when playing against a friend over a stranger. Meanwhile, local multiplayer enjoys ‘enjoyment and increased wellbeing’ advantages over online multiplayer with a clan or friends, which then enjoys an advantage over public multiplayer with strangers. Clearly, the closer you can get to emulating playing a game with a close friend on a sofa, the better. This is simply the kind of social environment we’ve evolved to resonate with most.

(Image credit: Nintendo)

However, to say being social on multiplayer is friends or bust is to miss an entire part of the equation. Games have tremendous capacity to allow us to make new connections – to increase our social capital. There are two main forms of social capital to be gained and reinforced – bridging and bonding. The distinction between these being that bridging involves loose, outward-looking ties we’d often associate with wider community – ‘social support, tolerance, and informational access’ facilitated from a diverse spread of people. Social bonding on the other hand encapsulates the inward looking, altogether stronger ‘emotional, material and social support’ from our closer, less diverse ties. MMOs by design seem to foster both, but bridging especially as a result of game design that has collective, regular real-time interactions (with strangers or distant connections) made necessary to complete in-game tasks. This is whether you’re motivated purely by individualistic achievement or not. So long as time investment doesn’t lead to less social embeddedness and investment in the real world, you don’t stand to lose any social support. It’s a win-win for devs as well. Whilst you enjoy all the benefits of social capital, you’re more likely to invest your human capital in the game in terms of pure time and investment (potentially monetarily).

My mind goes back to the controversy over the original Destiny raids lacking matchmaking. This to me now seems like it was indicative of the growing pains of the MMO-lite shooter contending with some of the social consequences of its genre mash-up. Whereas matchmaking with strangers might have allowed for more bridging like a traditional MMO with such socially demanding tasks, Bungie took the conservative position that only those already socially bonded were positioned to handle the demands of requisite collective gameplay. This is more reminiscent of the traditional online first person shooter design that they were acquainted with. Games are for

We can assume then that a first person shooter (FPS) like Bungie’s former Halos with their more limited social apparatus (compared to an MMO) can’t possibly compare in their bridging or bonding potential? In fact, whilst a comparison shows that the social infrastructure of MMOs makes a difference, FPSs like Counter Strike are almost as effective in both bridging and bonding. This would be astonishing if not for the ‘but.’ More time invested in World of Warcraft reliably leads to more social capital, whereas in Counter Strike it doesn’t.

The answer to why lies in our beloved Animal Crossing. As a social media juggernaut, Animal Crossing evidently must be a social capital success to some degree. However, I’d say this is completely in spite of its systems. Sure, a few Nook Miles rewards and the promise of diverse resources outside of your own island encourage multiplayer visits, but the experience is really little more than a cutesy MTV’s Cribs. Various websites having their own version of ‘celebrity island tours’ brings this show and tell nature home. In reality, it’s social media, streaming and forums that take all the strain of making Animal Crossing a social hobby. To bring the analogy back in, if the top-down paving stones don’t permit the growth of shoots, those shoots might be forced to grow around the stones through social media. Animal Crossing protests only make sense in tandem with Twitter. Otherwise, it’s just protest groups campaigning into the void. Nor is Twitch chat an efficient means of individuals communicating. Any social capital you stand to gain from Animal Crossing is most likely determined by your existing social capital on these sites. As I’ve pointed out before, even with what should be searingly lonely single player experiences like the brilliant The Longing, communities do their best to fill the voids they perceive in the games they follow. I think it speaks more to the social tools of these sites that they let people enthuse together over the balm that is Animal Crossing. How much does Animal Crossing come into it really? In Counter Strike’s case, it’s your willingness to engage with online clans and form connections outside of the game that significantly prime you for bridging in-game. When we call a game social, then, it’s worth discussing how much of that is the game itself. A game’s virtual culture might arguably have to encapsulate social resources in and outside of the game.

(Image credit: Valve)

Are these asocial games forced social, then, or social games with some external priming? Whilst you could make the argument that any activity could well be made social with the involvement of social media and community sites, it’s at least true FPS games have the capacity themselves to facilitate social capital. It’s just a matter of degree. Animal Crossing, like many Nintendo products, is much more tuned to provide a safe space for the reinforcement of existing social connections. Visiting a friend’s island is like visiting their house. A space to wander mindlessly as you chat is social enough for the already bonded. The highly aforementioned publicised meets in Animal Crossing are mostly significant as statements rather than anything that can be achieved in-game. I’d go so far as to say there’s no significant bridging potential in-game given you’ll have run out of things to do together in five minutes and the in-game keyboard on a Switch is impractical. The bridging for loose connections is in the organisation of meeting in the first place. Animal Crossing has succeeded in spite of how unconducive to community it really is. Ed Nightingale makes a good argument contrariwise, however!

Like Animal Crossing, you can see how FPS games with less in-game social systems could mean for even less social capital potential than Counter Strike. The lack of a server browser or private matches (matchmaking-only) or significant player-use of system-wide (console) party chat or external chat software, for instance. Transferring results of social processes outside of the game without flexible ways to meet or having any further unique bridging without being able to hear strangers could be difficult. Also, if social processes exist mainly outside of a game, only a small proportion of players will ever likely engage with them. The majority might well settle for the isolation of solo matchmaking with strangers. Whether we think of a virtual culture as encapsulating its community outside the game as well as in or not, the social systems in-game can still have an individualising effect.

There’s another ‘but,’ this time for our favourite MMO. Motivations matter. A separate study of World of Warcraft found that its top-down design decisions to require collective gameplay only significantly bridged capital in already socially motivated players. You could well say, those that don’t need it anywhere near as much. This is in line with the ‘rich get richer’ hypothesis – that it’s players with preexisting social skills and networks that benefit the most from gaming’s social resources. More asocial players with individualistic motivations might be less likely to see this bridging, but obviously stand most to gain from it. This shows the limitations of even the games that bake social capital into their design the most. It tells a tale of two experiences of online gaming. Those with preexisting social motivations get ‘increased feelings of happiness and well-being, increased online civic and political engagement, and the formation of both long-term online and offline relationships.’ Those motivated by gameplay, seeking other things like escapism, progression, accomplishment, etc, see more negative outcomes of addictive tendencies and the degradation of relationships with friends and family. Even if the top-down paving stones permit and encourage the growth of shoots, bottom-up factors of whether the shoots are primed to grow also matter. The asocial can clearly even become more asocial from losing their real-world social embeddedness and bonding capital with no gain in-game to counterbalance it.

This alone seems a devastating finding in terms of the public good social gaming can offer even at its most optimal. However, I’d be interested to know how real world activities compare in morphing asocial participants into social ones and it doesn’t seem to fare any worse than social media. It’s certainly not damning of gaming’s social power for those that seek it and thus is providing the service where it’s wanted. Still, it’s worth then thinking about what else primes online gaming to work its magic. We know some less socially complex games need external priming from sources like social media to allow for social capital gain themselves. What else? A player’s cultural values certainly could. A study on social network games showed that a gamer’s cultural orientation indirectly affects how they play a game by changing their expectations and motivations going in. Generalising values across a population is much less predictive than assessing people individually. Vertical individualists, for instance, have a higher likelihood of prioritising advancement (and levelling), which is consistent with a want to compete for status. Horizontal collectivists who prize equal relationships with group members actually saw status seeking behaviours negatively predicted. Instead they would lean into mechanics that involve mutual exchange. Having the cultural values of vertical collectivism was the most predictive of all: with higher usage patterns of advancement, avatar customising, publishing, and spending real money. This is likely due to the fact such individuals are more likely to conform to group norms, including keeping up with where friends had advanced to. It’s interesting that your cultural baggage affects what you engage with most in a game, especially if individualistic cultural values bias you against acquiring social capital. As World of Warcraft demonstrated, top-down funnelling of such players into collective activity by tying it to advancement isn’t effective.

(Image credit: Zynga)

When I think of how games monetise through the social dynamics they cultivate, I think of individualism. The new brand of MMO-lite games like Destiny 2 have something of a ‘shopping mall experience’ approach to a social space about them. Their hubs surround you with strangers but with no significant means of interacting with them. You’re all there for your own individual aggrandizement with no common tasks through which to unite you. When I think of battle royales that have conquered the online space in recent years, I think of people carving out personal status through competition much like they would with careers in an individualistic job market. If such a game has non-cosmetic microtransactions that increase your chances of domination then we even get a dose of simulation of the current dysfunctional late-capitalism that we all know. However, my intuition on this may well be wrong. Whilst enjoyment and advancement are important, a study found that it is community identity and interpersonal influences, not other individualistic motivators that most influence in-game purchases. Customisation to express individuality, for instance, wasn’t found to be significant. This aligns with the study that points to vertical collectivist populations in particular being predicted to spend more money in games due to their social systems. In fact, World of Warcraft players are more likely to mimic each other’s appearances so as to belong to a particular guild/community. The obscene (purely cosmetic) microtransaction revenue of the likes of Overwatch and Call of Duty could well be due to conformity to community trends or their friends’ appearances too. It’s suggested this even explains why the free-to-play business model of games is so much more effective in east Asian countries such as Korea, China, and Taiwan. It might seem underhanded to systemise a game like a social media site so as to weaponize your connections against you for profit… full stop. That said, motivating these purchases is existential for these free to play developers. I think we can consider it an upside that providing a platform for bridging/bonding and community – sharing our lives, opinions and time together rather than alone – is incentivised by microtransaction psychology. Building all the components of a social media platform within a game rather than leaning on those outside has its advantages. Destiny 2, however successful it’s microtransactions were, with only its presentational nod to wider community is likely still missing a trick here.

What can we say of the contribution of player demographics? Is there a shift in how generations engage with online gaming? It looks that way. Generation Z male gamers are significantly less motivated by competition and more interested in using gaming to connect with friends than the millennials who preceded them. This strikes me as a shift away from individualistic motivations. It’s interesting to contrast this with the finding that in World of Warcraft it is older players (50-57) who have the most max-level characters; a sign of more individualistically motivated game usage. Gen Z gamers watch video games on platforms like Twitch and YouTube 25% more than millennials. Streaming and videos truly are the heart now of gaming culture. This is a mixed blessing in terms of the great bridging potential streaming has through its online communities, but the celebrification of streamers should also be noted. Compared to being involved in a game, thousands watching a single influencer seems like individualisation, but with a collective layer on top working in concert. Potentially a partnership between individualism and collectivism. It’s possible, with YouTube gamers saying they spend more time watching gaming videos than playing games, that streaming and videos simply feel more social. Viewers get to know and bond to the people they watch over many hours. Engagement with and acknowledgement of comments and chat allow for in-jokes and ultimately community. Additionally, 68% of Gen Z males say ‘gaming is an important part of their personal identity.’ Given it’s such a significant part of their social infrastructure, this appears as if they’re buying into a collective, common identity. It’s worth also mentioning that although generally less virtually embedded, as with general internet use, online gaming also helps halt the decrease in social capital with age and thus could be valuable to older gamers.

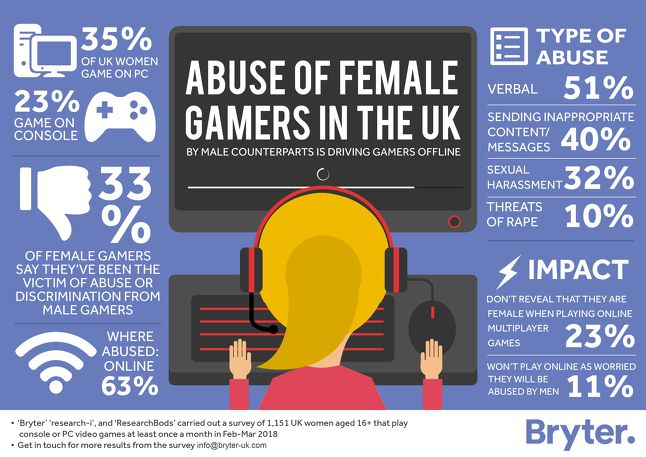

There’s a common thread of purpose in all of the examples for individualisation. Safety and anonymity. I’ve mentioned that I interpret the MMO-lite genre in the vein of Destiny 2, Fallout 76, and even Star Wars: The Old Republic as an individualisation of the MMO genre through their top-down social system design. This is probably a bit of a half glass empty response to what could be equally interpreted as former shooters starting to open the door to the more socially complex possibilities of MMOs. All the same, it’s those design decisions that kill opportunities for bridging that they have in common: a focus on being single player, story-driven RPGs; prioritising voiced NPC dialogue over player interaction, a focus on playing co-op with pre-existing friends, other players being mostly aesthetic, etc. It’s interesting that Fallout 76 in particular was widely celebrated for adding more traditional single player content in its ‘Wastelanders update’ rather than attempting to better fulfil its original player-only vision. It was the safe option (in more ways than one), but I’d say there are rumblings of a yearning for that social focus in so many of the stories of creativity expressed by players who persisted in the controversial title. However, perhaps the loss of certain social systems, as with the option to avoid player versus player (PvP) servers, is a price worth paying to avoid unmotivated griefing, bizarre in-game classist abuse, and the sexist, racist, sexually explicit, homophobic, transphobic, religious discrimination, etc abuse that we’ve come to expect of online experiences in general. Games clearly struggle moderating their own corner of the real and virtual colliding. Socially intersectional as online spaces are, there will always be no end to people looking to stamp their own image onto a community by pushing everything deemed ‘other’ out.

(Image credit: Bryter, Research-i and ResearchBods)

System transformations like the addition of console party chat, profanity filters, and in-game controls for disabling voice/text chat protect people from abuse. Matchmaking allows many to never collide with hostile players with antisocial and dangerous behaviours – anything from griefing to swatting – again. Whilst many bemoan Nintendo Online feeling a decade behind the times as a service, the roadblocks in its usability like friend codes and phone app-voice chat work in its favour. You can put your child on Splatoon 2 and never have to worry about Call of Duty-esque lobby toxicity or diving into child friendly settings otherwise. Animal Crossing multiplayer is a laborious pain to organise, but at least you’ll never have someone visit your island without you knowing about it. It’s effectively out-of-the-box conservatism on the issue. Even with Hearthstone’s aforementioned culture of emote-usage you can block emotes from your opponent (known as ‘squelching’) to prevent any harassment from the limited tool. Whilst social experiences yield oh so many benefits the individualisation of these experiences might actually allow players (particularly vulnerable ones) to engage with social play on their own terms. Without this kind of protection online gaming could be the preserve of the abusive or those who aren’t likely targets.

However, now that we live in a world of deep learning AI, AI policing like that of Minerva, the FACEIT and Google-designed ‘Admin AI,’ could well become the first line of defence. If everything from voice, text and in-game behaviour is one day filtered accurately, then everyone should be able to play with confidence. The removal of more socially complex or integrated systems would no longer be necessary. With existing increases in accessibility likely having already played a great part in increasing online gaming’s popularity, perhaps AI will allow the marriage of more complex social systems à la World of Warcraft with the safety of more socially conservative multiplayer releases? Of course, what’s to stop abusive parties from engaging in an arms race with their AI overlords and inventing new covert ways to offend, much like the profanity filters which let insultingly obvious variants of their targets slip through or Hearthstone emotes? Technological solutions to social problems just feel inherently unsatisfactory, but it’s a start, and it certainly helps from a workload standpoint. Their AI banned 20,000 toxic CS:GO players in six weeks. Until such an unguaranteed tech panacea does arrive, developers need to show and not simply say that this is important. Have report systems with teeth. Care that your players are forced to hide away or swear off your games altogether.

The most fascinating multiplayer release of recent years to my mind is probably Pokémon Go. The game launched in July 2016, but social features like battling against other users were only added almost two years later in June 2018. It became a force of social nature, then, not because of any particularly deep social features, but because it led to massive face-to-face congregations of players on the hunt for Pokémon to catch. It was almost in spite of a dearth of social complexity then that it became the craze that it did. The best thing it did was to simply facilitate the social capital that comes from encouraging you to occupy common areas in your locality, even with largely individualistic goals. 46% of its players play in groups even when there’s no advantage to doing so. You need only look at this map of communities it’s cultivated to see the impact of that simple mechanical push. Similarly, there’s been a new wave of tabletop gaming that has allowed gamers to graduate to a more socially-conducive face to face setting for their interests. As for the riskiest kind of social gaming app – it has to be dating apps. Like most online games they’re imbued with a virtual culture. The disdain for the profile tiger selfie comes to mind – a value of an otherwise largely disconnected, individualised community of users. Whilst these apps are likely predominately used by only the most socially motivated in society, I do think they’re generally emblematic of the appetite for more of such exposing, more social online experiences, even in spite of the real risk they carry. Tabletop and augmented reality/location-based game communities fulfill this with more safety and inclusivity. Online multiplayer has this potential too.

Given Gen Z’s increased appetite for using gaming for social and community-based experiences, I think it will become ever more unlikely that we’ll face another Metnka119 AI imposter in a game like Mario Kart Tour. Instead, a Metnka119 will be monitoring all of us racing – ensuring it’s safe and accessible. Instead of human competitors being hardly indistinguishable from Metnka119, deeper social systems can lend their power in enriching our hobby with social capital potential. This will light up our brains, increase out wellbeing and better connect us to society. Everyone deserves only the good of online gaming – the thrill, the cultural-transfer, the community, the connections. No exceptions.

It seems apposite that in the age of individualism we all live alone on our own islands in Animal Crossing. In the COVID era, we all have 1-4 metre bubbles that mustn’t be breached and masks of anonymity. Community is on pause (or at least it should be). As in the Dark Souls series, we occasionally invade each other’s worlds, but only with significant pre-planning or pre-existing connections. Social media, which should fill the void left by individualisation, can also be subject to the same limitations as online gaming. There is disappointment upon lockdowns being lifted around the world that society seems to have only been transformed for the worse with the status quo upheld alongside the economic damage inflicted. My hope is that virtual communities can one day help by being better tooled to be resources for social capital acquisition. One day Animal Crossing’s Nook will find an island big enough for all of us. Until then, *greetings reaction* from afar!

*Dark Souls Carving: VERY GOOD*

Terrific piece!