A Brief History of London in Games

Writer’s note:I feel it would be irresponsible to begin this article without first mentioning the situation that has been occurring at a number of Ubisoft studios, whereby a group of individuals have been disciplined, fired, or have stepped down over reports that they contributed to a toxic company culture and allegedly engaged in cases of sexual misconduct. Although the following feature contains a number of references to Ubisoft’s games, I wouldn’t want the publication of this piece to distract from the ongoing conversations that need to happen about abusive workplaces in the games industry or to absolve Ubisoft of their failure to provide a safe working environment for their employees. I encourage all readers to spend some time familiarising yourself with these allegations and to join others in demanding more from the company’s leadership. You can find out more information from reading Ethan Gach’s report for Kotaku, and Jason Schreier’s recent investigative piece for Bloomberg.

From the looming spectre of St Paul’s Cathedral to the modern skyscrapers that crowd the streets today, London is a city of great contrasts. A modern metropolis constructed out of glass and cladding, it is home to phantoms of the past in the Georgian and Victorian-style brick buildings that dwell beneath its skyscrapers, and the slumbering Thames which snakes between the banks of luxury apartments that are erasing the remnants of the city’s industrial past.

For artists and creatives, London has come to symbolize many things within their work. From a place to make one’s own fortune to a hotbed of corruption, scandal, and grisly crimes committed under screaming gaslight. These associations appear across multiple mediums, but especially within video games, where countless developers have tapped into these associations to create virtual playgrounds for players. Whether that be the gothic Victorian setting of Assassin’s Creed Syndicate or the grim and violent open world of The Getaway.

With the world currently in lockdown and an incredible number of people using video games as a means to escape their homes, we thought it would be a good idea to view a single city through its multiple interpretations within games. And what better location to select for this project than the English capital, London: home of overpriced beer and the tears of promising games journalists made to live on 17k a year.

A City Made of Blocks

Grand Theft Auto London was arguably the first release to allow players to explore the city freely. Cutting through the streets of swinging 60s’ London in this expansion to the original Grand Theft Auto, players could complete jobs to earn cash and evade the police like the star of their own crime caper. It was the fantasy of a criminal London as depicted in The Italian Job and Get Carter, albeit with the viewer possessing the autonomy to derail the story for their own individual amusement.

Ironically, the UK-based DMA Design wouldn’t be responsible for creating the map of this popular expansion. Instead, it was left to Rockstar Canada and one of its programmers Blair Renaud to dream up a version of London to slot into the GTA universe, an individual who to this day claims to have never set foot inside the real city. Using a custom-built map editor, he constructed GTA’s London out of 3D tiles, with the textures created in Deluxe Paint. Fellow Rockstar employees Ray Larabie and Greg Bick contributed the tile art, but Renaud was the person who was responsible for putting it all together, a fun but daunting task.

“We used basically everything we could get our hands on for reference material,” Renaud tells me over email. “I remember watching a ton of car chase movies from the late 60s like The Italian Job, Bullitt and Robbery to get the vibe we were going for. Ronin had also just come out and I remember being hyped for that. As for the map itself, I basically cleared the reference material from the local book shop (the internet still wasn’t great in 1998). Everything from tourist guides and visual dictionaries to just plain old road maps. Basically, anything that had any pictures or information about London was fair game.”

The final result found within the game is a top down version of the city that incorporates many of its most notable landmarks. Westminster, Tower Bridge, Piccadilly Circus – you name it. However, due to the technological restraints of the time and the blockier layout of the map, huge creative liberties had to be taken, with Renaud comparing the process to building in Minecraft. Nevertheless, he believes should he ever visit the city he’d know his way around pretty well as a result from his time buried in its maps.

While not the most accurate depiction of the city found within games, it’s a fun novelty to see Grand Theft Auto’s anarchic action injected into the usually bustling streets of the city – a factor which has likely contributed to the location’s appearance at the top of the most-requested areas for future games in the series.

Staging The Getaway

The Getaway followed in the early 2000s, bringing with it new innovations, such as being able to explore a 3D recreation of the city on foot from a street-level perspective, as opposed to overhead.

Taking inspiration from the works of British filmmaker Guy Ritchie (Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels and Snatch), as well as Paul McGuigan’s film Gangster No. 1, players could explore an early 2000s version of the city, speeding through the grimy London backstreets, while fighting off corrupt police officers and gangs in pursuit of their kidnapped son.

Ravinder Singh Ruprai was the art director on The Getaway at Team Soho. Over a voice call, he details many of the challenges posed by the production. Chief among them being the lack of manpower and the number of tools that were necessary to create a London at the scale they envisioned. The Getaway had originally been a PS1 title, but part way through development the game had shifted to Sony’s upcoming PS2. With that jump to a new platform, Ruprai and the team realized that the level of expectations had been raised, and that meant scaling up the art team to achieve this leap in fidelity.

To get reference for the project, the team would constantly send artists around the streets of London to take shots, an advantage of being based in Soho. Using basic digital cameras, the team would wander areas that would later appear in the game, locations such as Marylebone, Bloomsbury, St Pancras, Southwark, and Clerkenwell, to name just a few.

“I remember just taking a camera around those areas, around Southwark and Borough,” says Ruprai. “Around some of those really dingy old backstreets. One of the lead engineers…had this really old Mercedes, from like the 1970s or something. We just drove around there and took a few shots of us…standing next to this old battered Mercedes on these old cobbled, dingy, grimy sorts of backstreets of London. Just to get an idea or a flavour of ‘Yeah, this is definitely the direction we want to go in.’”

Despite the occasional artistic embellishment, Team Soho’s depiction of London was remarkably accurate for the time it was made, not least because of its use of company logos and real billboards — something that feels incredibly cavalier looking back on it today. According to Ruprai, the advice that Sony’s legal team had presented them with, was that they were okay to replicate brand logos, as long as there was a shop or a billboard in that exact location at the time.

“The thing that we had to be mindful of is we couldn’t build every variation [of the sandwich shop] Pret a Manger,” explains Ruprai. “So we had to ensure that if there was a Pret on a certain street, we would use two or three Pret models that we had and make sure that it was a Pret and not a Starbucks in its place.”

Despite these precautions, this approach did eventually land them in a spot of bother shortly after the release of the game. According to a statement provided to The Register at the time, the telecommunication holdings company BT complained about the use of one of its vans over fears it may “incite attacks on [its] engineers”. This was followed by another issue in which a billboard had to be removed after a complaint was made by a photographer. In both cases, these complaints were dealt with swiftly, with the team simply replacing the assets used.

However, video games set in London aren’t just about gangsters and getaways. There have been various depictions of a more gothic London, with developers manifesting a myriad of monsters into the metropolitan streets to terrorize players. This has included everything from zombies to werewolves to vampires and folkloric figures from history.

An Undead London

According to creative director and artistic director Florent Sacre at the French studio Ubisoft Montpellier, their goal for Zombi U was to create a credible and sensitive version of London for as wide an audience as possible. Albeit within their technical means and with a hint of “fantasy and romanticism” to the environment.

While Grand Theft Auto London and The Getaway portrayed a London of cops and robbers, the London created for Zombi U is a lawless place, where what remained of the police had largely been absorbed into the throngs of the infected.

Players must venture through the streets of London and into the city’s underground, scavenging materials to fend off hordes of the undead, aided only by a voice over the radio. Along the way, they will encounter ambulances and taxis piled up blocking the streets, while makeshift medical tents hint at the prior struggle to contain the outbreak.

For the art team, the goal was to present something authentic, which meant visiting the city and documenting the city for reference. Talking about the pre-production on the project, Sacre explains, “We went to spend a few days in London with [the narrative director] Gabrielle Shrager…and [the writer] Antony Johnston. We bathed in tourist places and quieter, more intimate places…More real [spaces]: kindergartens, squares, parks, workshops, simple alleys, factories, etc…I wanted to feel the real London.”

Sacre and the team took a ton of reference during this trip, but alongside these sources the team also referenced a selection of other media to develop the game’s look. These include the works of Gustave Doré, the paintings of J. M. W Turner, the photographs of American photographer Gregory Crewdson. That’s not to mention the influence of Danny Boyle’s 28 Days Later and Charlie Brookers’ pre-Black Mirror TV series Dead Set — both of which also took place in a post-apocalyptic version of modern Britain.

Though authenticity was arguably important, the team didn’t try to map out the entire city, instead sticking to only a few selected areas including the Victoria Memorial and Spitalfields, locations accessed through underground tunnels. Their aim was to create an environment that felt believable, but that was designed to be satisfying to explore — something that proved more challenging than you might think.

“The real world isn’t custom built to be fun,” explains Thomas Casamento, one of the eight level designers on Zombi U. “You have to create places that look realistic, but where you can bring gameplay [in]…Reality doesn’t care about rhythm either, [such as] if you’ve already walked the same trajectory twice to go from one street to another or if you’ve visited two big places in a row that would have made perfect places to meet enemies, etc.”

Despite being considered a commercial disappointment for Ubisoft upon its initial release, Zombi U has earned something of a cult reputation among players, with the game’s depiction of a post-apocalyptic London being among its greatest achievements. There’s just something so unsettling about its depiction of London, even without the presence of flesh-eating zombies, with the visual language employed to depict the city and the outbreak skewing unnervingly close to scenes that have become more prevalent in recent years.

The London Gothic

Following on from Zombi U, it wouldn’t take Ubisoft Montpellier that long before the French studio returned to the English capital, albeit this time during a different time period.

Set in 1868, during the industrial revolution, Assassin’s Creed: Syndicate sees the conflict between the Templars and the Assassin Brotherhood relocated to a smoky London, ruled by gangs and unscrupulous industrialists. Orphans toil away in workhouses, while the River Thames flows with tireless trade, and the city’s workers bustle to and fro transporting cargo along the narrow streets.

While the main team behind the project was the Canadian studio Ubisoft Quebec, Ubisoft Montpellier assisted on the game, putting together the Whitechapel environment — the area players first encounter upon starting the game — as well as its Jack the Ripper DLC. They drew from a few different sources of inspiration for this district, but the outline for how they approached the area started with the roads.

“We had to work from macro to micro with the artists because all the districts in Syndicate were modulated by the roads,” comments Vincent Barrieres, a level designer on Assassin’s Creed Syndicate and its Jack the Ripper DLC. “To start, we created the flow of the roads, because obviously in the game there was the possibility to drive a carriage with horses. All the districts were all constructed around the roads. So it was the first step for us to have the layout of the level…” From there, the team would then start putting together the individual districts found within the game.

Betrand Bergougnoux, a level artist on the Whitechapel district, explains, “My brief…was to bring more organic feeling in the way we apprehend and feel the district…More like a little village inside the massive city of London with a more claustrophobic, intimate feel, and more torturous-steep streets, compared to some of the other districts, which were mainly…wide boulevards with huge buildings and slums.”

In order to accomplish this, the team used a mixture of historical research, influences from literature, film, and TV, as well as personal reference.

Bergougnoux, for instance, found inspiration from the Ecusson district of Montpellier where he was living at the time, because of its similarities to the English capital. He travelled around this area of Montpellier taking pictures of its steep streets, narrow alleys and back alleys, as well as the messy architectural layout, with the goal to replicate these aspects in-game. Other sources he also found useful at the time included old engravings, photos, and historical maps of London, as well as the work of Dickens, and TV shows like Penny Dreadful, Peaky Blinders, and Ripper Street. These sources, along with Alan Moore’s graphic novel From Hell helped them to inspire a darker, grittier version of London.

What this resulted in was a London that feels meticulously researched, but where you’re never far away from celebrity cameos from celebrated figures such as Dickens, Marx, or Darwin. Without mentioning notable London bogeymen like Jack the Ripper or Spring-Heeled Jack. It’s an area where landmarks are painstakingly reconstructed in exorbitant detail, but where generic gangs populate street corners, gurning menacingly. Even today, it’s a strange and uncanny feeling to walk through its streets or gaze upon the city from above, with the game mixing the folkloric with the historical to create an amalgam of both.

A London To Sink Your Teeth Into

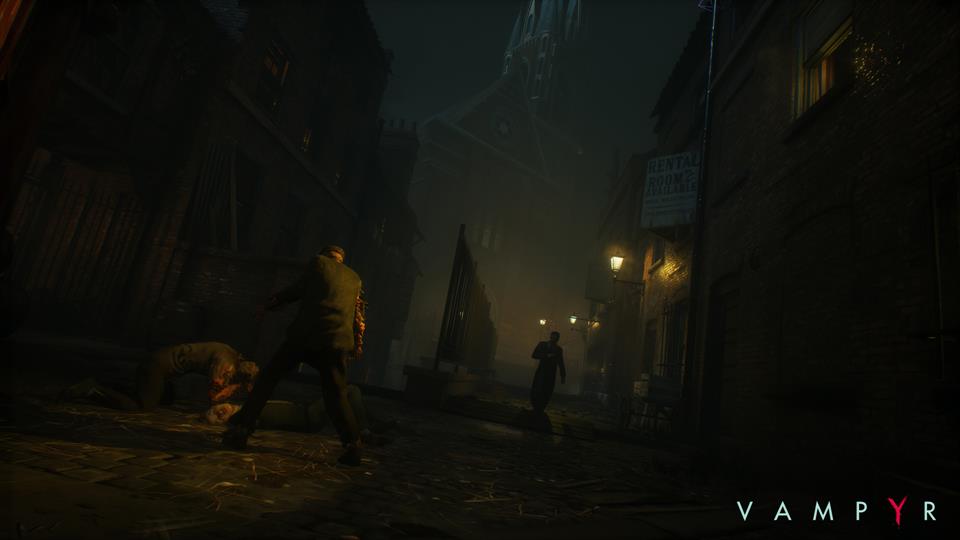

Ubisoft weren’t the only ones to do this though. Ready at Dawn also released The Order 1886 around the same time, a cinematic third-person action-adventure game that followed the Knights of the Round Table battling a horde of vampires and werewolves in an alternate history version of Victorian London. This was followed shortly after by another similar title, Dontnod’s semi-open world action-adventure game Vampyr, in 2018.

Vampyr focuses on the story of the doctor Jonathan Reid, who returns to London after the end of The Great War in 1918, only for a vampire to attack and transform him into one of the undead. Players must traverse a stylized recreation of London that includes Southwark, the West End, and Whitechapel, helping survivors of the ongoing Spanish Flu Pandemic, while coming to terms with Reid’s newfound condition.

In Vampyr, the London you explore is an extreme depiction of the city. Violent vigilantes wander the street, while a criminal gang called the Wet Boot Boys try to capitalize on the quarantine keeping people inside, roughing up shop owners for protection money.

“We [didn’t] want it to have a realistic look,” says Gary Jamroz-Palma, a concept artist on Vampyr. “Our goal wasn’t that…we wanted our London to give you hints about…the world…you are playing in, only by the look. So that’s why…we kind of exaggerate certain landmarks. We were huge fans of Dishonored and they had a really stylish way of showing things, like huge windows, huge gates, huge doors. And we wanted to recreate that feeling of something that you would see in London, but…not exactly at the right scale.”

Besides Dishonored, which itself drew inspiration from the Victorian painter John Atkinson Grimshaw, the Vampyr team also took great influence from From Software’s action-RPG Bloodborne, both in terms of its approach to level design and the dramatic use of silhouettes.

Interestingly enough, Bergougnoux and Barrieres, who previously worked on Assassin’s Creed: Syndicate, were also part of the Dontnod team that helped construct Vampyr’s cityscape. For them, it was a much different production this time around, with Dontnod having a significantly smaller budget, a different engine (Unreal Engine 4 in contrast to Ubisoft’s own AnvilNext Engine), and reduced numbers of personnel. Bergougnoix estimates that at its peak there were only 9 environment artists on Vampyr, a world of difference when compared to the hundreds of artists and modellers who had contributed to Assassin’s Creed: Syndicate and its multiple DLCs. This meant the team had a lot more freedom to operate independently of one another and to take initiative where possible.

“When I started working on it, they said, ‘open up the engine and let’s load the map’ and there was nothing,” recalls Barrieres. “Everything was empty, so I was like ‘okay’…I said ‘Does the artist work with me?’ And they just said, ‘Oh no, you’re going to do the alpha of the city in blockmesh and greybox.’ It was a totally new approach for me [from how I had worked at Ubisoft Montpellier].”

The London of Vampyr is a sick London. Taking place shortly after the end of the First World War, hospitals are still in ruins, as they try to cope with the escalation of the Spanish Flu pandemic.

For the art team, they wanted their portrayal of London to symbolize the state of the citizens within. Which meant looking into the medical practices of the day, through historical documents as well as other media such as TV shows like Steven Soderbergh’s The Knick, to find ways of conveying that meaning to the player. In the game, the main hub location Pembroke Hospital is the result of these efforts. A bombed out refuge in the middle of the chaos, it’s as much a character as its inhabitants, with its boarded up windows and tangle of wooden beams and supports just barely holding it together.

While the PR line when it comes to the representation of real places in games is often all about how close a games studio can get to the real thing, the true strength in video games is in their ability to create brand new worlds to explore, even out of the ones we already recognize.

Though artists and designers rely on quick visual shorthands and cultural histories to conjure up these alternative worlds for players to inhabit, there’s an infinitesimal list of considerations and decisions that combine to create the impression that we see on screen. And though we can likely sit and pick apart their incongruities and anachronisms, that doesn’t mean they’re any less real, representing the ideas and the labour of those who conceived of and laid every last brick.

Nice article, i love the aesthetics of victorian london, so i have played Vampyr, The Order and Assasins Creed Syndicate. I leave in Mexico and i havent been to london, but pretty cool to read about its representation in games.

Greetings.